Tatum O’Neal

America’s favorite tomboy taught a generation about gender, chutzpah, and loss

The story properly begins not with me, or with my childhood crush on Tatum O’Neal, but behind the scenes with one of the unsung women of Hollywood, Polly Platt, who, after all the flings and shenanigans, became the first female art director to be accepted into Hollywood’s prestigious Art Directors Guild. Perhaps owing to her massively influential husband/collaborator, Peter Bogdanovich, she was perceived as both his and her own person.

But with and without her creative partner, she forged a new aesthetic, at the time when filmmakers like Hal Ashby, Louis Malle, Robert Altman, and then John Hughes rose to replace the old guard. It was mostly assumed that her ideas had come from the brains of male directors, producers, screenwriters, and actors.

When the chips were down—after Bogdanovich destroyed their marriage (by running off with Cybill Shepherd) and compromised their creative partnership—it was Orson Welles (while bingeing on tapioca pudding) who restored Platt’s confidence. He roared into the phone for Platt to “Come and work for me!” And then he won her over with a giant mound of his very theatrical homemade steak tartare.

Platt became a seminal, and in many ways subliminal, operator in some of the biggest box office movies of the ’70s. She adapted Larry McMurtry’s Last Picture Show (1971), worked on What’s Up Doc? (1972), A Star Is Born (1976), and Pretty Baby (1978). From ’85 to ’95, she worked extensively with James L. Brooks spawning hits like Terms of Endearment (1983), Broadcast News (1987), and The War of the Roses (1989). She also mentored upcoming screenwriters like Cameron Crowe, and helped develop Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982). She was influential to the ’90s, helping the next generation of filmmakers like Wes Anderson produce Bottle Rocket (1996). Platt also helped inspire the creation of Matt Groening’s The Simpsons.

Is that enough? If you look back at the ’70s, it is clear that Platt was instrumental in igniting a fresh wave of cinema—leaving producers like Robert Evans behind like a rocket slowly lifting off the earth. Her achievement in Paper Moon (1973) was like the last gasp of an old era. And her next project, The Bad News Bears (1976), was the first gasp of a new era. Between ’73 and ’76, she was an invisible agent for alchemy in multiple genres.

She was a cool and colorful woman. And a lover of vodka, which made her a lot of fun to be around. But there were ups and downs, and she self-medicated and ultimately survived in the industry, sprinkling everything she worked on with bits of her own biography.

Designing sets for A Star Is Born, she conveyed the light and dark side of her characters’ psyches in subtle ways. She claims in her unpublished memoir to have placed Kristofferson, for example, “in a huge darkened house with no furniture except for a cherry Harley Davidson motorcycle in the living room,” while Barbra Streisand’s character required “a clear beautiful rosy light.” This sums up her gut instinct for motion pictures, where color, a specific prop, the choice of a location, the revision to a script, the casting of an actor against type, the placement of a throw pillow with a memorable pattern on a sofa, or the natural light achieved by shooting at the golden hour could, and often did, make a scene memorable.

One film that thrived on Platt’s creativity and touch, was Paper Moon—it racked up 18 Academy Award nominations and won eight, and launched Tatum O’Neal’s career at the age of 10. And three years later, Platt used Tatum again, in the deceptively compelling The Bad News Bears, a film that killed it in the box office and inhabited the collective consciousness of a generation of children in ways that are still incomprehensible.

Paper Moon was based on the 1971 novel by Joe David Brown, Addie Pray, about an orphaned tomboy named Addie, who rides shotgun with her adult partner, an experienced conman named Moses (aka Moze, circa the ’30s, in the time of the Great Depression). Addie learns the skills of being a thief and a confidence girl, working with Moze. Their scam involves selling Bibles to God-fearing Americans. But they also trick store clerks into mismanaging their cash registers (they exchange bills like magicians doing card tricks). It’s ambiguous if the two thieves are father and daughter, although they both seem to wonder if they are genetically linked to the same wild woman, who we never meet—the story begins at this enigmatic woman’s funeral.

When Platt heard what the boys at Paramount (including Bogdanovich) had in mind for Paper Moon, her first instinct was to run and hide. But she was coaxed back into action by a team that sensed the film needed one less “yes man” and one more “no woman.” She convinced her husband that the tired old director John Huston—who was planning to cast Paul Newman and his daughter Nell Potts—was all wrong. She had a better idea: to quarry a brand-new piece of marble.

Platt had recently come across a natural-born actor at a Malibu beach party at the home of Ryan O’Neal (whom she’d worked with on What’s Up Doc?) on the cliffs overlooking the Pacific. It was Ryan’s 8-year old daughter, named after the stride pianist Art Tatum (he laid the foundation for bebop, vis-à-vis Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk).

What could have possibly been so artistic to Platt about Tatum? Was it a hunger for attention? Was she too accustomed already to freedom? Had she been prematurely overexposed to the glory and horror of adult situations? Did her charisma come from a necessity to cleverly shift attention away from an embarrassing, philandering parent? Regardless, Platt took notice when Tatum turned it on, and she immediately envisioned Ryan & Tatum tangoing on screen exactly the way they did in real life.

Platt immediately got down to convincing Bogdanovich by reading from the script in Tatum’s husky voice, imitating the child’s charm and hard-to-define duality of maturity and childishness—defiance (was it?) with a touch of humility.

Tatum was not a spoiled brat. If anything, she suffered from neglect. She lived (along with her brother Griffin) on a ranch in the Valley with her mother, Joanne Moore, a train-wrecked diva from the ’50s (she appeared in the film noir classic Touch of Evil in ’58, and hit her peak in the ’60s, starring in Hitchcock Presents, Perry Mason …). Moore became addicted to a deadly combination of amphetamines and booze, acquired numerous DWI’s, and finally sputtered to a lonely death. In her memoir, Tatum describes how she’d tag along with her mom to bars and fend for herself, as her mom got loaded and flirted with a coterie of young boyfriends. Tatum tells how she eventually sought refuge with her father in Malibu, only to find that he too had a revolving door of ubiquitous mistress-actresses.

According to Karina Longworth’s incredible podcast You Must Remember This, which thoroughly documents Platt’s career, Platt basically made Tatum into an overnight star, but also contributed to both Paper Moon and The Bad News Bears in many other subtle ways. She created the overall visual aesthetics of the two Tatum vehicles—both of which positioned Tatum in the passenger seat of a car with a dubious fatherlike figure at the wheel, driving the dialogue with her foul mouth and blunt delivery and irreverent attitude. But it was Platt who was driving Tatum—or enabling her to discover the intoxication of appearing in front of the camera.

Polly certainly molded Addie Pray into her own vision, creating a bleak retro road movie shot strikingly in black and white. She argued that the deep forests of Georgia (the setting in the novel) would dwarf the characters, imagining the “ill-matched pair” in the flat grassy planes of Kansas instead, where they would stand out against the vast sky, appearing far away from “the comforts of home.”

Platt went even further: sharing a family photo she had of her father sitting in a big quarter moon with an unknown sexy lady who was definitely not her mother. This became the central motif for the film (see the poster), and inspired the title. Says Platt: “I was always very curious about this picture: who was that woman? I showed the photo to Peter and suggested a scene in the carnival where Tatum wants her father to sit with her in the moon booth to have her picture taken, but he never shows up because he’s off chasing after a hoochie-koochie dancer.”

At the end of the film, Addie leaves the coveted photo in an envelope in the car as a sort of melancholy goodbye letter to Moze, as we hear the classic song “It’s Only a Paper Moon.” The lyrics are remarkable:

You smile, the bubble has a rainbow in it

Say, it’s only a paper moon

Sailing over a cardboard sea

But it wouldn’t be make-believe

If you believed in me

Yes, it’s only a canvas sky

Hanging over a muslin tree

But it wouldn’t be make-believe

If you believed in me

Without your love

It’s a honky-tonk parade

Without your love

It’s a melody played in a penny arcade

It’s a Barnum and Bailey world

Just as phony as it can be

But it wouldn’t be make-believe

If you believed in me

If you love me, in other words, this phony world will become real. And what about this phony Hollywood movie with its canvas sky? Ironically, the metaphor exposes Platt’s own discipline designing sets and directing art, in order to make the artifice of Hollywood film sets convincing.

Platt made Ryan O’Neal and his real-life daughter Tatum into convincing partners in crime—placing them side-by-side on her fantastic paper moon. But this required that she swallow her pride, join back up with her husband/collaborator who had just broken her heart by entering into an open affair with an actress Platt had herself plucked for the The Last Picture Show, Cybill Shepherd. When it came time to start production, Platt made one demand: to ban Shepherd from the set.

Platt put all of her focus on Tatum, who was then seen as a feral child. She had very little schooling and could hardly read the script. She also lacked formal training as an actor and was thus unable to maintain focus during long shoots. It was freezing on the set. Platt remembers Tatum shivering in the little summer dress she’d designed for her, and zipping her inside her coat to keep her warm.

But an emotional burden weighed on Platt’s conscience—the way Paper Moon mimicked Tatum’s antagonistic and often abusive relationship with her dad. In the film, Addie seeks love and approval and protection from Moze, but also sees through his lies with growing contempt. She has the cleverness to toy with him, but without the agency to call her own shots or break away.

According to Platt, Tatum was not able to distinguish between fiction and reality. She was facing the dangers of method acting, without any hands-on acting experience. On set, she was the center of constant attention but, as Platt questioned, “how was a child to know all this attention was our job?” This thought reveals the psychological disconnect that may have triggered Tatum’s future fall—seemingly disabling her later in life from ever getting her feet on solid ground. “I thought about how hard it was gonna be for Tatum after the picture was over and she became just a little girl with a drug-addicted mother and a woman-chasing father.” In her memoir, Platt goes on to express guilt for causing, or at least contributing, to Tatum’s “inflated sense of importance.” She admits that she “knew that eventually all the attention would be gone, and that Tatum would just be a little girl again.”

Paper Moon came out and Tatum O’Neal did inflate. She won the Academy Award for best supporting actress, becoming the youngest actor ever to receive an Academy Award. Many felt she deserved even more credit: best leading lady.

Tatum first caught wind of her nomination while visiting her dad on the set of Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. Folklore has it that when she told him about the news, Ryan, who had been overlooked, expressed jealousy by giving Tatum a hard punch to the head. Child abuse right out there in the open.

Amazing as Tatum is in this performance, and iconic and penetrating as the film may be, the blockbuster slips into the same old car chase, between the same old cops and robbers. It’s all about stuntmen doing the fancy driving. And yet, Paper Moon has the face, neck, shoulders, hair, subtle morphing expressions, and very punchy attitude of Tatum O’Neal—and it has therefore held up beautifully. Later in life, Tatum would appear for a few seconds now and then on camera between points up in the stands watching her husband, John McEnroe, play tennis at Wimbledon, and she would leave the same sort of indelible impression—by virtue of her gaze and the mystery of her concentration.

Exciting things do happen in Paper Moon before the film starts to seem tedious. Right off: An art deco font used in the opening credits startles the mind! Then, in the opening scene, Moses Pray (as the name says on his business card) arrives late to a funeral, steals a bouquet from a tombstone, and crosses the graveyard to join a small group of mourners. He whispers something into the grave about the buried woman’s ass still being warm (apparently, he was well acquainted with Addie’s mother).

It is implied that Addie, while hardened and self-reliant, and endowed with the ability to “add” numbers quickly in her head and account for her money—especially the $200 Moze stole from her—faces a difficult challenge without a grown-up to care for her. Moze plots to callously offload her at a nearby train station. He buys her a ticket to a far-off town where some distant relatives await, but after an argument conducted over a Nehi soda and a Coney Island (hot dog), Addie and Moze (with his fake gold tooth and buffoonish persona) decide to stick together. She envisions a role for herself in his criminal enterprise and she clings on tight. They hit the road side-by-side in Hollywood’s front seat. It’s cinematic bliss.

They pass various refugees (victims of bankruptcy and starvation) on the side of the road, which reminds us to forgive them for their immoral transgressions ripping off innocent people as a matter of survival (in the Darwinian sense). They save up a stash of loot, which allows Addie to tend to the narrative’s next problem: that of being a tomboy.

Addie wants to look and feel more like a girl, but she’s stuck in a pair of dirty overalls and her mom’s dated flapper hat, which has lost its sex appeal. Moze agrees to stop at a clothing store in a small town and together they cop her a more feminine wardrobe. But Addie hasn’t been groomed, or taught etiquette, and she speaks in a bossy boyish tone; she sees the world through a fierce masculine gaze. And to make matters worse, she smokes cigarettes, which are forbidden for women (not to mention children). Addie carries her smokes and other tiny possessions and holdings in a Cremo cigar box that reappears menacingly in nearly every scene. The Cremo logo is often blocked by other objects creating suggestive word play. In one scene it reads as “emo.”

Addie (or Tatum) seems to enjoy smoking a little too much, as she lays in bed in a hotel glued to various radio shows dreaming of FDR’s New Deal. But she’s frustrated by her appearance. “I ain’t a boy!” she complains. And her dad-ish partner provides an insincere (and corny) reply, typical of a slick con man whose words have no meaning: “You’re beautiful! And your mother was beautiful. They wouldn’t even let her come to Holland for fear she’d droop the tulips.”

In the next hotel, Addie gets out of bed in her boy’s underpants and “wife-beater” style undershirt, like a mini Marlon Brando, and tries to strike a feminine pose in the mirror. She hangs a cheap beaded necklace around her neck, and splashes her mom’s remaining perfume all over herself, attempting to magically transform herself into a sexy woman. Is this yet another movie mogul’s Lolita? A cultural fascination with prepubescent girls arriving at the moment of desire of becoming the object of desire? Is it a realistic representation of a little girl coming of age?

The perfume splashes on the camera lens (accidentally, I assume), breaking the fourth wall—and creating a seamless transition to the car’s spattered windshield, the next day, which is when the two buddies seem to realize they are a compatible and codependent team, something like lovers.

The car and the road also begin to meld. Tires skid across gravel, kicking up a cloud of dust which drifts toward the camera, and nearly dissolves the scene—owed to special camera filters and expert cinematography.

They arrive at the county fair, where Addie eats cotton candy, while Moze waits in line to enter the “Harem Slave” tent behind the working men in overalls. Moze tells Addie to play a little bingo or “write a love letter to Roosevelt,” and quickly reappears accompanied by a “dancer” he met inside the tent. Trixie Delight is, just like that, his new appendage. Also along for the ride is Trixie’s servant, a Black girl roughly Addie’s same age named Imogen. The degrading racial stereotype is cringeworthy, and yet, presumably radical for its time—pointing to the preposterous dynamic of presumed white superiority and feigned Black inferiority. The depiction harks back to the parables of Mark Twain, as if Paper Moon has merged with the raft in Huckleberry Finn. The vulgar compromised prostitute (perhaps no different than Addie’s own mother) is a significantly higher-ranking member of society than the African American girl who politely jumps to the whore’s every whim and treats her like a queen. The film, to its credit, displays the disgrace and humiliation of the universal hustle, that to some degree, we all take part in.

The team of four then moves on down the road—however, now with Trixie sitting up front riding shotgun and Addie demoted to the back of the bus. Their exhausted 1930 Ford Model A convertible gets traded in for a fancy new 1936 Ford V8 De Luxe convertible. While Moze enjoys his new car and catch, a revealing albeit cartoonish friendship forms in the back seat between Addie and her new friend. Addie offers Imogen a cigarette and the two kids trade winks. Later Imogen will compare Trixie to “that little white speck on top of old chicken shit.”

At a pitstop, Addie’s protest begins. She climbs up a hill and parks it, with no intention of getting back in the car unless her status in the front seat is restored. Trixie yells from the car “This baby gots to go winky tinky!” Moses starts up the hill and tries to talk Addie back to the car.

“I ain’t comin’!” says Addie with more intelligence than mere stubbornness. Moze explains, “Miss Delight and me are sittin’ in front because we are two grown-ups and that’s where grown-ups do the sittin’!” Addie responds: “Well, she ain’t my grown-up and I ain’t plannin’ no more to sit in the back. Not for no cow!

It’s now up to Trixie to coax Addie back to the car, and she tries a different tactic. This is when the actor Madeline Kahn gets truly outrageous: “Nobody started to call me ‘Mademoiselle’ until I was seventeen and getting a little bone structure.” She points to her chest. “You’re gonna have ‘em up there too … And I’ll see to it you get a little bra or somethin’.”

Addie grins and looks at Trixie, seeing her as the shallow eye candy that she is, which triggers Trixie’s true bitch: “you’re gonna pick up your little ass,” Trixie says, “and you’re gonna drop it in the back seat, you’re gonna cut out the crap! … Let ole Trixie sit up front with her big tits.”

Is that what this is all about? Tits?

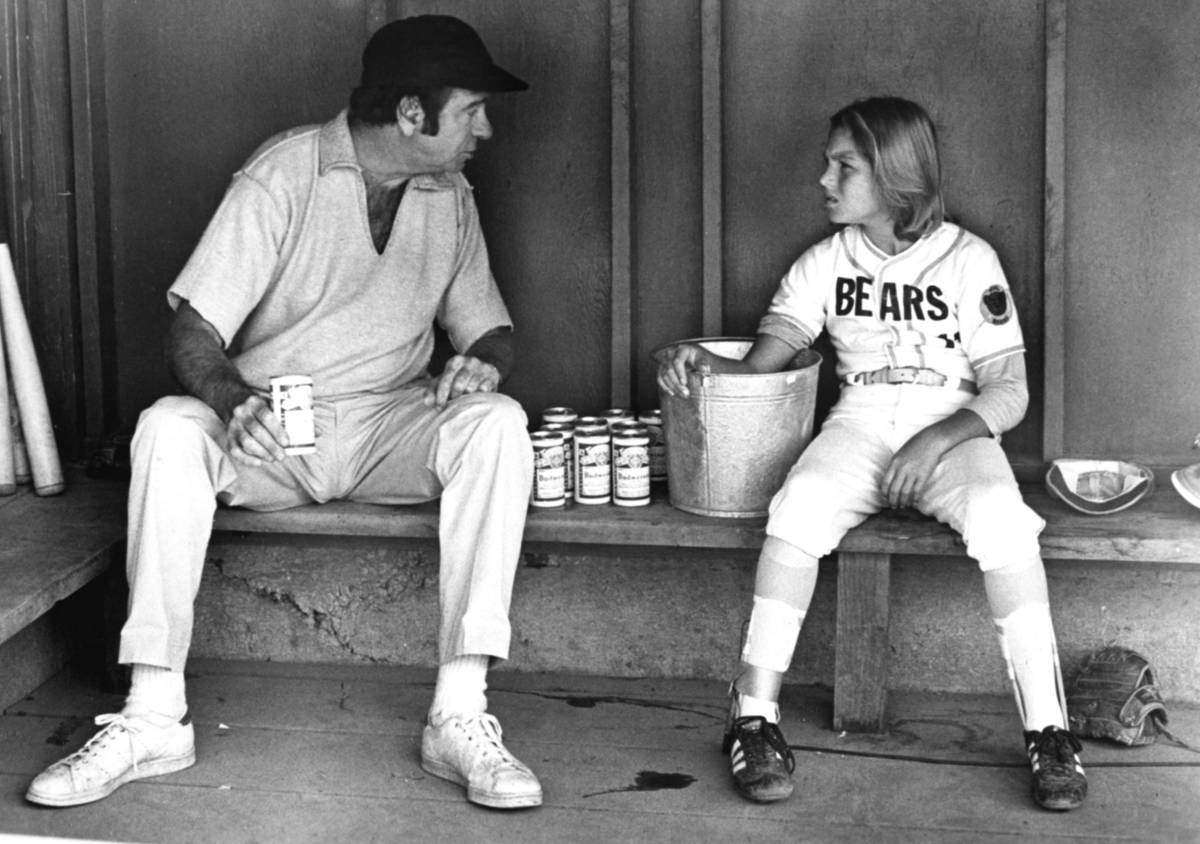

Platt moved on to her next ’70s masterpiece-in-the-making, bringing Tatum along. Paper Moon ends with a girl and her father in a car driving off on a winding road. These archetypical pals make a U-ie and drive right back at us (moviegoers) into the suburban sprawl of LA, this time in a light blue 1964 Cadillac DeVille convertible, missing the door on its trunk, outfitted with a Styrofoam cooler full of cold Buds (as well as Coors, Schlitz, and Miller), a couple baseball mitts, and the coiled hoses used to vacuum pools.

The driver is named Buttermaker. He is the quintessential Little League loser, played by the grumpy Walter Matthau. Every feature on his face droops in a poochlike fashion creating sympathy. If the Academy had the category best punim (Yiddish for face), he surely would have won many times. According to various BNB trivia sites, the Buttermaker role was initially offered to Steve McQueen (who turned it down), and then to Warren Beatty, who signed instead with Reds (not the Cincinnati Reds, who won the pennant that year).

We have by now crossed over, with Polly Platt’s shapeshifting creative promiscuity, to a new generation of moviegoers (families). The Bad News Bears no longer struggles with the past, but carves a massive wake into America’s reckless and hopeless future.

Working with an entirely new team—writer Bill Lancaster (son of Burt), director Michael Ritchie and producer Stanley Jaffe—Platt found in Walter Matthau a new flawed father figure for Tatum. According to Jaffe, Matthau was a curmudgeon with “a heart as big as this world.” There is no doubt he was just the right mensch to play the schmuck. The film, which was never meant to be quite so good, became a compelling allegory for America’s failing democracy in an election year, as well as a stunning follow up for Tatum O’Neal, who had already made it big, but was still only beginning to blossom.

Unlike Paper Moon, with its variety of period interiors and moving outdoor settings, BNB is situated almost entirely in a ballpark and in the present-tense pop cultural zeitgeist of the mid-’70s. Platt insisted they “make the diamond the world.” Rather than hunt for the perfect Little League field, she built one from scratch, so that her diamond would work with the sun at the golden hour without portions falling into shadow. Every frame glows.

Platt also kept most of the irrelevant parents and spectators in the background, allowing the motley kids and their dopey coach to dominate in a set consisting mostly of distressed forest-green dugouts, bleachers, an announcer’s box, a scoreboard, chain-link fence, and a home run wall with memorable texture and character.

In one scene the team’s fat catcher Engelberg and the nerdy bookworm Ogilvie, climb over the outfield wall, collapse in exhaustion, and hide from their coach who is working them too hard. They look like two WWI soldiers in the trenches. Engelberg pulls out a candy bar, chomps into it, and chews it up paper and all, while Ogilvie pulls out his asthma inhaler and takes a puff.

The outfield wall takes center stage again, later in the film, when Lupus (the team’s runt who hardly fills out his uniform) drops back with his dreamy blue eyes lost in the clear sky till he arrives at the green wall. He reaches back and suddenly feels his glove sag from the weight of the plummeted ball. Trumpets and xylophones sound, and Lupus is shocked as everyone else to discover what’s in his mitt. He’s stolen a homer like a pro center fielder, reaching beyond the outfield wall.

Paramount’s producers were also shocked by their big catch. When making the film, the executives were split on whether the Bears should win or lose, and they actually shot both a happy and a sad ending before knowing which one they’d insert into the final cut. The film’s producer, Jaffe (who received a degree in economics from Wharton in 1962) insisted that BNB was about trying, not winning. According to his logic, “One person wins. But everybody tries.” Jaffe—who also made it big with Fatal Attraction (1987), and Kramer vs. Kramer (1979)—found that the same people who try are the ones who buy movie tickets.

The Bad News Bears was released on April 7, 1976, and trying people (like me and my sister and brother and parents) came in droves—the film shot past its expected $9 million, and kept going till it reached $42.3 million, with the popcorn buttermakers flowing ‘round the clock.

Paramount was initially concerned that the authenticity of the baseball scenes and lingo would not be understood by a broad-enough audience (and especially a foreign audience), so they added a five-minute animated baseball primer at the beginning of the film dubbed in five languages. Perhaps this was unnecessary.

The film begins with Buttermaker, in his car. He’s a case study for downward mobility, judging from the entropy of his Cadillac, which would have at one time been a genuine status symbol. After a brief stint pitching in the minors, he’s become a pool cleaner. He wears khakis and beat-up Stans (the all-white Adidas with the green tab at the heel) and, in a few scenes, a madras shirt and seersucker blazer suggestive of preppier days on country club tennis courts. And yet, down and out as he is, Buttermaker seems to be perfectly content going nowhere.

Buttermaker, we quickly learn, has not been hired to form an able squad of competitors, but rather to assist the league’s assorted losers in fading, without a fight, into the forest-green woodwork. His job is literally to round up all the rejects and get ‘em all onto one bench.

Tatum was perhaps one of the first girls that kids my age saw buckle down, concentrate, and demonstrate what it takes to throw a strike—let alone to strike out the side.

Buttermaker (or Boilermaker, as he is often called by the kids who have watched him snatch a bottle of Jim Beam from his glove compartment and empty a slug or two into his beer can) sticks to his ethics—assuring every player on his equal opportunity team that they will get up to bat. He sticks with this philosophy when a disgruntled parent challenges his authority. “Is it really necessary to send in that Lupus kid now?” pleads the parent, who is fed up with losing.

“He hasn’t played yet,” says Buttermaker.

“I know that. But we still gotta chance.

“Well everybody on my team gets a chance to play.”

“Oh come on! Don’t give me that righteous bullshit!”

Buttermaker finally orders the parent back to the stands before he “shaves off half his mustache and shoves it up his left nostril.”

At one point, Buttermaker packs the entire team into his boat-convertible and brings them along to help clean a pool. The work is done, and happy hour begins. The camera pans back, revealing Lupus, of all people, expertly putting the finishing touches on a martini by inserting a toothpick through an olive and delicately placing it on the edge of the glass, exactly as a seasoned bartender would do it—as Buttermaker describes to his wide-eyed Bears a young female pitcher he once coached named Amanda Whurlitzer (whom we are yet to meet) who had “the most tantalizing knuckler you ever saw in your life. I mean this thing was a thing of beauty.” Buttermaker stops to take the first sip of his martini and smoothly acknowledges his bartender with a slight nod as he continues describing how the little girl’s pitch “came up to the plate and disappeared. It was like a ball of melted ice cream.” He then turns to Lupus: “That’s superb. [Sip]. Thank you very much.”

In the Bears’ first preseason practice, Buttermaker arrives at practice too shit-faced to even stand up and he passes out near the pitcher’s mound, provoking Tanner Boyle—the Bears’ inbred, blond-haired redneck with serious anger management issues—to boil over: “Look, you crud, just get back to your beer! Get going!” At another point, Tanner shames his coach, saying “all we got is a cruddy alci for a manager.”

Buttermaker’s public inebriation is embarrassing, but it’s equally shocking to see just how uncoachable and dysfunctional his boys really are. The next practice Buttermaker stands at the plate hitting pop flies and ground balls to his inept infielders and outfielder, who can’t catch or throw. He turns to his catcher, Engelberg, who is morbidly obese (although by today’s standards not that fat) and says with astonishment: “There’s chocolate all over this ball.”

The kid is crouched behind the plate, stuffing another partially wrapped melted candy bar through his face mask. He then takes to his feet and unloads on his coach: “Look Mr. Buttermaker. Quit buggin’ me about my food. My shrink says that’s why I’m so fat. So you’re not doin’ me any good … so just quit it!”

Rather than push back at a kid who is obviously a casualty of rampant consumerism, and getting iffy psychiatric advice, Buttermaker—an alcoholic in his own downward spiral—calmly backs off. “OK … OK … OK …” he says, in a soothing tone.

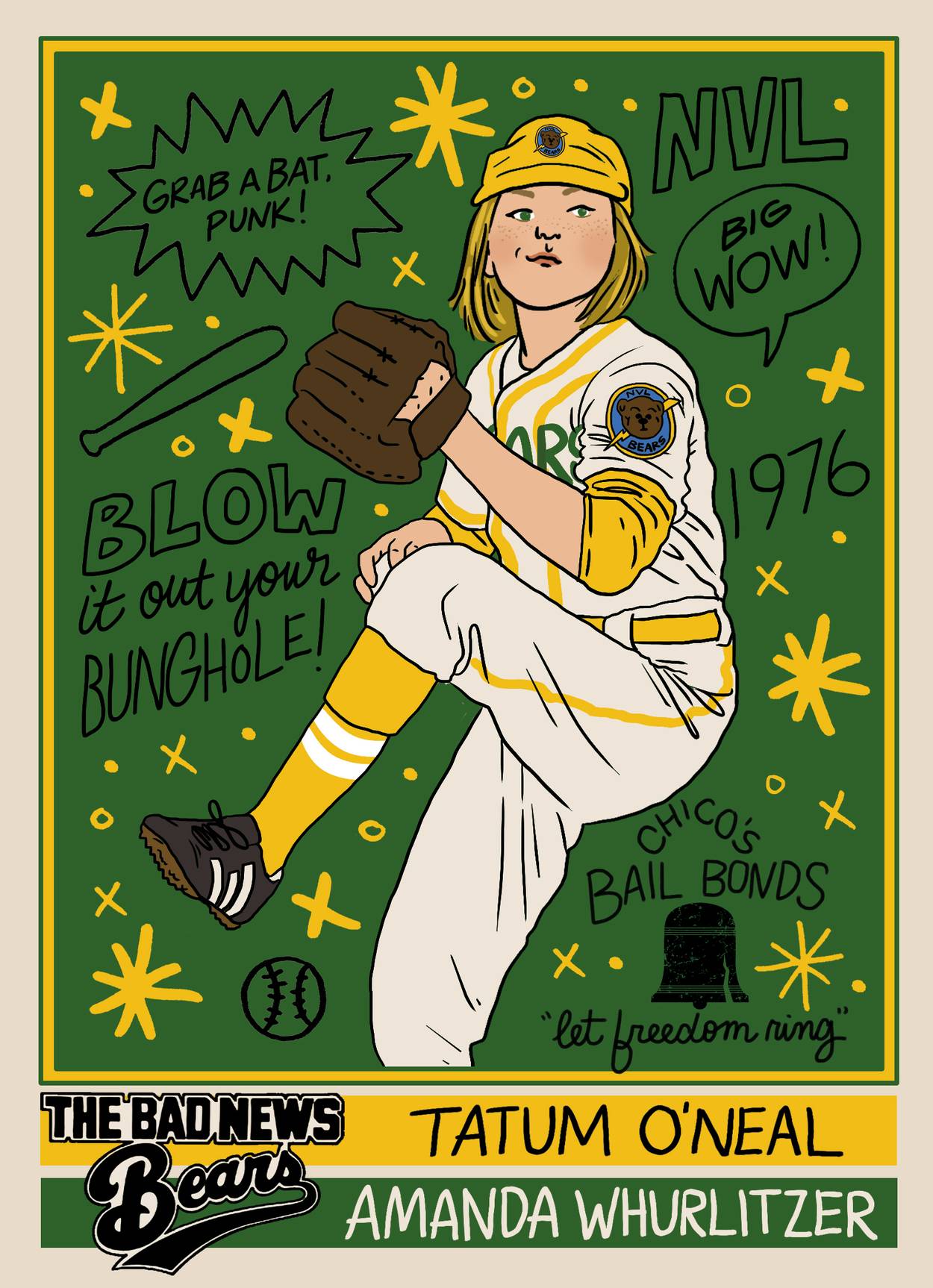

Somewhat miraculously, Buttermaker actually delivers the team their uniforms, just in time—arriving with a tall stack of boxes. “I’ve been out getting what you little creeps have been bitching for—uniforms!” He pulls out a sharp-looking white jersey with yellow trim and an outlined number “1.” It’s an object of pure beauty (paid for by Chico’s Bail Bonds).

The kids now look like a team, even if they can’t play like one. Alas, the season opener is a total wipeout. After allowing 26 runs to score in the top of the first without a single out, Buttermaker weaves a little off-kilter out of the dugout carrying his Schlitz tall-boy and crosses home plate to speak with the Yankees’ coach: “What do you say we call this off. It’s getting ridiculous.” He forfeits the game. The bum quits again.

He then marches back to his dugout planning to administer some group therapy to his sorry squad but discovers that the Bears’ representative Black Muslim player, Ahmad Abdul-Rahim, has run away, stripped off his uniform, and climbed a tree, ashamed by his poor performance. This sets the film up for one of its most endearing moments and proves that The Bad News Bears was in fact a serious piece of cinema gravitas underneath its screwball packaging.

Buttermaker climbs the tree and sits next to Ahmad who is just in his underwear.

“Leave me alone,” pleads Ahmad.

“This isn’t your tree,” says Buttermaker. “Anybody can climb up here.” He then insists that there was “nothing easy about the fly balls,” and that “the sun was in his eyes.”

“Don’t give me any of your honky bullshit Buttermaker!”

“Let’s not bring race into this R-Man.” Says Buttermaker, as he lights another of his plastic-filter-tipped cheap cigars. “We got enough problems as it is.”

The conversation continues: “Thank God Hank Aaron didn’t act like this,” says Buttermaker.

“What?”

“Don’t give me that ‘what!’ You know what I’m talking about!—the 42 errors!”

“42 errors?”

“Come off it, will ya R-Man? Stop pullin’ my leg. You know all about Hank Aaron. His first year in sand-lot ball, he committed 42 errors. He was nine years old. Broke his little heart. He damn near quit …”

“Buttermaker you’re so full of shit …”

“—IT’S COMMON KNOWLEDGE for cryin’ out loud. Ask Ogilvie.”

The scene gets even more touching, when Buttermaker talks R-Man into envisioning a more positive season for himself. “I was thinkin’ right around the 3rd or 4th game you’d be switch-hitting. I figured with your speed … you’d be a tough out … You know, bunts … things like that.”

There’s a long pause. “I am kind ‘a fast huh?” says Ahmad.

There’s another even longer pause. We look into Buttermaker’s eyes, then at the slanted line of his mouth. “You’re VERY fast.” It’s that authentic Matthau emotion. The way he inflects the word “very” creates goosebumps.

Buttermaker takes his own advice. He sees a better season for himself too, and he begins to teach the kids a few fundamentals. He shows one batter how to firmly plant his back foot before taking a swing. He demonstrates how an infielder should get his body behind a ground ball in order to block the unexpected bad hop. Buttermaker is building skills and confidence, lifting his team from the bottomless pit of low self-esteem to the world of high expectations. Ogilvie reads off the stat sheet, reminding his coach that despite their “24 errors,” and the fact that the other team’s “pitcher threw a no-hitter” the Bears actually played pretty good baseball. “Two of our runners almost managed to get to first base,” he says cheerfully. “And we did hit 17 foul balls!”

Still, Buttermaker knows what his team really needs—the girl with the melting knuckler. Off he goes to recruit her, arriving somewhere on Mulholland Drive where she’s sitting in a foldout lawn chair selling Star Maps and flipping through a fashion magazine. She looks a little too grown-up for her age, in a white-flowered peasant top and an ankle-length patterned wraparound skirt, and a wide-brimmed sun hat. She could be modeling for a Matisse.

“Pretty fancy neighborhood you’re working these days, Amanda,” says Buttermaker as he gets out of his car and walks toward her. He plants a tender kiss on her temple the way a father would. “How’s your mom?”

“What’s it to you?”

“Is that the way to talk to me? I haven’t seen you in two to three years?”

“Well if you’re looking for money, you can forget it!” Amanda continues to unload on the poor guy. “You made my mother sick! You know she wanted to marry you. Boy was she dumb.” She goes on in her demoralizing tone. “You’re not my father and I ain’t interested in playing baseball for you anymore. So why don’t you get back in that sardine can of yours and go vacuum the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.”

It seems that the Buttermaker was simply not a good enough breadwinner. But he returns a few days later to try again. This time, he uses the same sort of reverse psychology that worked on R-Man. “There’s nothing to be afraid of,” he says, tossing the ball repeatedly into his mitt.

“I’m not afraid. I’m just through with all that tomboy stuff.”

“Baseball’s not tomboy stuff! It’s your country’s national pastime. It’s healthy!

Amanda tells of her plans to get braces and become a fashion model, and then returns to the theme at the core of Paper Moon. “I’m almost twelve and I’ll be getting a bra soon.” She says looking down at her skin-tight stretchy black tube-top that reveals a perfectly flat chest. “Well maybe in a year or so,” she says with disappointment.

“You’re absolutely right!” says Buttermaker. “You’re turning into a regular little lady. It was a dumb idea anyway. I mean you wouldn’t have helped the team much. I mean you were great when you were nine. Girls reach their peak athletically when they’re about that age.” He puts the baseball gloves back in his trunk.

On cue, Amanda suddenly has a change of heart. She stands up and offers to throw a few pitches. She lines one up, and torpedoes a very impressive pitch right on target. Buttermaker smiles, knowing he’s almost won her over. “When are we gonna see some curves?” he asks, in a moment of brilliant innuendo, and Amanda, who now seems motivated by something like testosterone, replies: “The next one’s coming right between your eyes.”

Next, we see this odd couple side-by-side in the front of the old Cadi sailing down some endless LA boulevard, wind blowing through Amanda’s blond hair. (So much for seatbelts, or drunk driving with a minor in the front seat.) She pulls the cigar out of Buttermaker’s mouth and throws it out (so much for littering). The negotiation then continues as, once again, the precocious daughter of Ryan O’Neal bargains for the best deal she can get: “I want the imported kind of jeans.”

“Jeans?”

“Yes, French Jeans.”

“I’m not getting you any kind of Jeans. Do you know how many pools I’ll have to clean …”

“—the expensive kind.”

“Imported jeans? What’s a matter with American Jeans?”

“I don’t like ‘em.”

Buttermaker walks Amanda Whurlitzer out to the mound (is she named after the type of organ that plays “Take Me Out to the Ball Game”?). It’s her first Bears practice. “Boys, I’d like you to meet your new pitcher.” Tanner immediately reacts—adding the female gender to his long list of deficient human beings (“Jews, Spics,” the N-bomb again, “and now a Girl?”).

Apparently, Tanner is not able to see himself in the mirror, nor to recognize his own marginal status as a piece of white trash.

“Grab a bat Punk!” dares Amanda, crossing her arms in front of her flat chest. She’s in a tight pink T-shirt with iron-on sassy rainbow decals and bellbottoms. When she fires her first supersonic pitch, we feel its heat and hear it crush the catcher’s mitt (it breaks the sound barrier).

Tatum was perhaps one of the first girls that kids my age saw buckle down, concentrate, and demonstrate what it takes to throw a strike—let alone to strike out the side.

Tatum was better than the decade’s two other tomboys, who both duked it out for the role of Amanda Whurlitzer—Jodie Foster dropped out to make Taxi Driver, and Kristy McNichol was asked to step aside.

Tatum summed her experience in an interview she gave some 40 years later expressing how amazed she was to wake up and find that so many people had fallen head over heels for her character’s careful blend of masculinity and femininity. “People love this movie … I love this movie!” She also gives away a little secret: Two boys (stunt doubles) were used to fire those hard and accurate burners.

You might be asking, what kind’a booger-eatin’ spaz cares about such crud? Quentin Tarantino and the late Philip Seymour Hoffman certainly care(d). Both masters, at one time or another, called The Bad News Bears their favorite movie of all time. Even if you weren’t fortunate enough to see it in theaters back in ’76 before you had hair down there, I’m sure by now you’ve absorbed it through the pores of pop culture.

The film was something of a wild pitch. Wilder than Jimmy Carter (the first presidential candidate from the Deep South to win since the Civil War); wilder than the Concorde (which took flight that year); wilder than Caitlyn Jenner, in her snug-fitting track and field uniform, waving that cute American flag on her victory lap, after winning the men’s decathlon at the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal. It could have been called the Bicentennial Bad-Ass Bears.

BNB wasn’t just about Tatum’s gender-bending curveball, knuckler, or fastball, or Matthau’s choice of whatever six-pack was on sale. It was about bad words. Never before had a family audience witnessed so many unabashedly offensive remarks. Tatum admits: “I don’t think you’ll see kids talk like that again in film. It was unbelievably non-PC.”

Perhaps the most bad-ass character in the film is the certified juvenile delinquent, Kelly Leak. We first find him in the outfield perched on his 1975 Harley-Davidson Z90 (Platt had an eye for such gems). He lords over things from a voyeur’s perspective in his rose-tinted Ray-Ban Aviator sunglasses, with a cigarette dangling from his lips. We see him hop off the bleachers, kick-start his bike, rev his throttle, flare his back tire, and peel off in one fluid motion, like an outlaw in a Western. He actually rockets down the third-base line and uses the base pad as a bump to catch a little air, before zipping across the outfield. Rad. That same year, Mr. Evel Knievel jumped 10 vans, surpassing his previous world record.

The day finally comes one practice when a deep shot to left field rolls past the outfielder. In an unprecedented moment, Kelly Leak jumps off his Harley, flicks his cig into the grass, and hurls the ball all the way back to home, skipping the relay man (or woman). It’s immediately apparent that he is the rock star they’ve all been hoping for. Indeed, the neighborhood’s ne’er-do-well turns out to be the most gifted athlete of ‘em all. But he sees jocks as the sworn enemy, and is committed to letting his athletic abilities languish.

Buttermaker employs Amanda to lure Kelly Leak onto the team. He drops her off at a seedy arcade somewhere, where he’s known to hustle people on the air hockey table. Amanda struts over to the table in that prideful yet vulnerable Tatum way, and challenges the intimidating boy to the next game. We witness the added bonus of their pre-pubescent flirtatiousness, as they begin hitting the puck around. They make a bet: If she wins, he will join the Bears. But what if he wins? We watch the puck ricochet twice and slip into the narrow slot behind Amanda’s paddle.

Amanda walks across the parking lot in her trendy outfit. She’s dressed like KC from KC and The Sunshine Band. She slams the car door, exactly as Buttermaker slams back yet another cold one. She reports the bad news—that she is now required to go with “the creep” to the (quote) “Rolling Stone concert.” Tatum actually seems to flub the line, saying the word “Stone” (singular) instead of “Stones” (plural).

“Eleven-year-old girls don’t go out on dates!” says Buttermaker, sounding ticked-off.

“Blow it out your bunghole!” yells Amanda, using the exact kind of words we all use when respectfully addressing our parents, parents’ friends, teachers, coaches, aunts, uncles, etc.). And there’s a long silence.

“What if he tries something …” asks Buttermaker, meekly.

Amanda looks directly at him with macho surety: “I’ll handle it.”

The Bears actually get Kelly Leak on the team, and he leads them all the way up the ladder. At one point, Buttermaker takes him aside and instructs him to go after every ball on the field. Which angers all the other players who now take pride in their positions and abilities. Buttermaker has gotten greedy for victory. It is noticeably unclassy. “I told you not to swing you idiot! … Sit down Engelberg. What the hell’s a matter with you? Next time I tell you to do something, god damn it, you do it! Or else you’re off this team!”

He sounds like every father ever to coach a Little League team. He’s finagled his own Catfish and Reggie. He thinks he’s an alpha in pinstripes? Which leads to the epic default pep talk of the century: “All season long you’ve been laughed at, crapped on. Now you’ve gotta chance to spit it back in their faces and what do you do? You’re out there like a bunch of dead fish. Bonehead plays. Mistakes! I mean, don’t you want to beat those bastards!?”

The camera pans across their fierce little faces—Amanda, Kelly Leak, Lupus, Tanner, Ogilvie, Engelberg, Regi, Miguel, Jose, R-Man, Stein. Buttermaker can hear his bark echo through the dugout and he decides to ease up. His face droops, he blinks, and he apologetically mutters: “Now get out there and do the best you can.”

At the final championship game, the Bears do the best they can. Every kid gets up to bat. Even the very small Mexican boy Miguel (younger brother of Jose), who doesn’t speak a word of English. His almost nonexistent strike zone allows him to draw four balls and he miraculously walks his way on.

The Bears don’t win the game. But it wouldn’t be correct to say they lose. At the game’s end, both teams gather at home plate for a trophy ceremony. The Bears are awarded a small second-place trophy, and the Yankees’ pitcher (in his eyeglasses) Joey Turner, who is the league’s nastiest bully, makes a semi-insulting condolence speech: “We just want to say, you played a good game. And we treated you pretty unfair all season, so we want to apologize. We still don’t think you’re all that good a baseball team. But you got guts! All of you.”

The Yanks throw up their hats, and the camera cuts to Tanner, who, at least has the audacity to say what he really thinks. “Hey Yankees!” he yells: “You can take your apology, and your trophy, and shove it straight up your ass!” A joyous celebration erupts around home plate, and out come the brewskis. The entire bunch of minors is suddenly pouring and spraying bottles of beer in each other’s faces—just like the pros. The camera pans back on the American flag to Bizet’s 1875 French Revolution opera, Carmen.

Here I am in my vintage yellow Bears cap like Bernie in his COVID mask and mittens (nay, mitt) sitting innocuously way out in the proverbial bleachers, still crushing on the electrifying Tatum, awestruck by the gonads of that kid Kelly Leak. But now I’m feeling like the film’s 50-something coach, and perhaps identifying a little too much with his epic sense of futility and failure. Buttermaker sits in the dugout icing his beers as Whurlitzer ices her sore throwing arm in a bucket. She’s grown attached once again to this older man and aspires to get him back together with her mother. Or to at least spend more time with him one-on-one off-season. “I was just thinking maybe we could go horseback riding or something. Or maybe go to a matinee.”

“Look Amanda you’re a terrific kid. You shouldn’t be hanging around with me. I mean I’m an old broken-down, third-rate ballplayer. I like to drink too much, I like to smoke my cigars without anybody bothering me, including you! I’m happy that way! I’m a bum!”

“No you’re not.” says Amanda sweetly. Like so many children, she believes in fairy tales. “You taught me how to pitch …”

“—GODDAMN IT!” screams Buttermaker, splashing beer from his can into her face. It’s a violent, unforgivable gesture. He has rage in his eyes. “Can’t you get it through your thick head? I don’t want your company!”

Amanda stands up and walks away. Her face is wet with tears and beer. In real life, this is the way the heartbreaking film would end. Or in real life does the party keep going, as the players continue to numb their pain and hide from reality and try to stay high?

Platt’s worst fears about Tatum came true—she kept abusing substances and being abused by volatile men. She was allegedly beaten by her father and molested by his drug dealer. Then came heroin and crack. It’s easy to speculate that she could have been verbally abused by her husband, the tennis star John McEnroe, judging by the way we’ve seen him talk to line umpires, and throw his racket in his tennis tantrums. What do you think—was it Tatum’s Irish blood, or that quarter Ashkenazi?

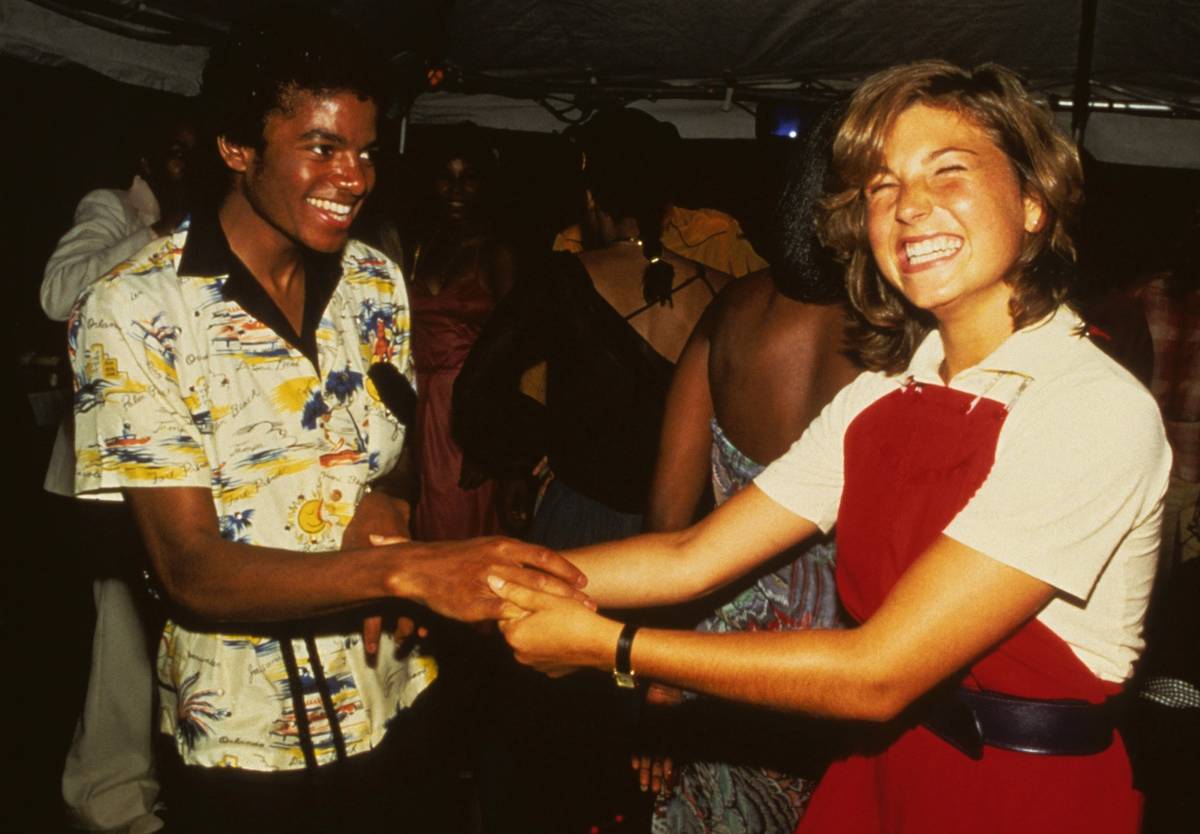

I discovered a picture of Tatum when she was very much at the top of her game. She was still in her teens, floating on some disco dance floor with Michael Jackson. It looks less like Studio 54 shot by some paparazzi, and more like a photo from a family friend’s bat mitzvah party. She’s in red overalls (overalls of all things). And she’s blushing. MJ, who is drenched in sweat, looks devilishly innocent as always. Is it puppy love? They were said to be dating. Tatum has spoken about their long hours on the phone back then. Jackson once put it like this: “I was, like, in heaven.”

Apparently, Michael and I aren’t the only two guys who fell in love with Tatum O’Neal. It’s fair to say that back in ’76, she was every boy’s favorite tomboy—the dictionary definition of “first crush.” Boys my age fell for what they saw on screen: her baffling gender-fluidity, her back talk to authority, her confidence in all situations, and concentration. But also her tenderness and honesty—and willingness to talk about her body. To an 11-year-old, a simple word like “bra” is mortifying. Tatum did convince us that she was genuinely a great pitcher, but even more that she was a genuine person. Boys knew when they left that theater that girls no longer threw like girls.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.