The Death of Glucksmann

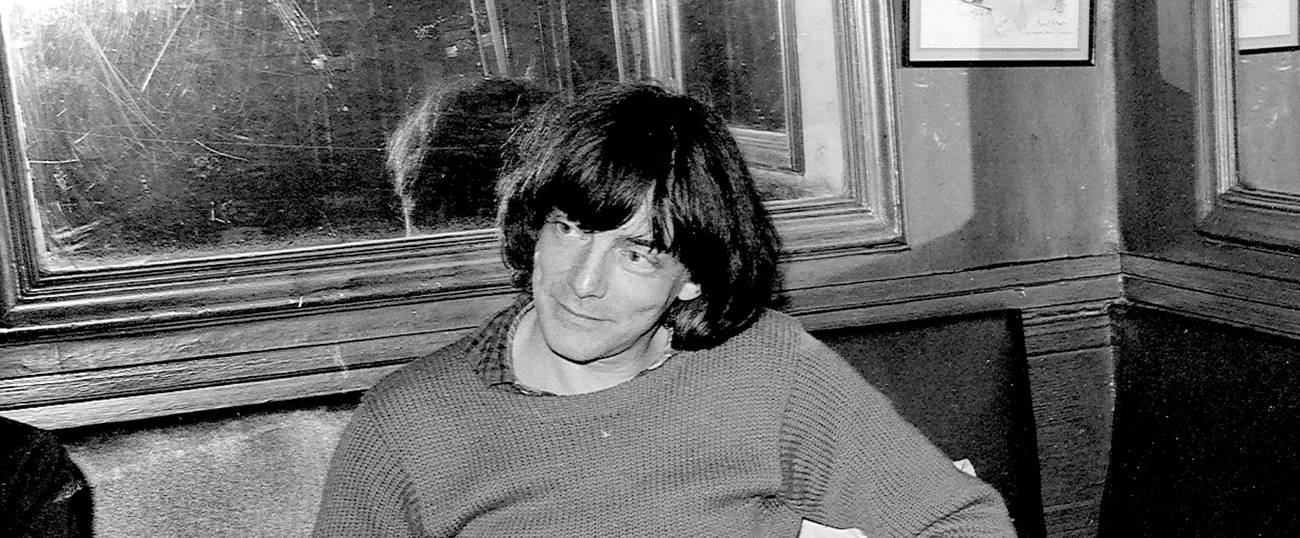

Remembering the French intellectual, a man of influential ideas

André Glucksmann was a great man, and he played a great role in history. I think that, in the world of ideas, no one in modern times has played a larger and more effective role in marshalling the arguments against totalitarianisms of every sort—no one outside of the dissident circles of the old Soviet bloc, that is. Even within those circles, Glucksmann and his arguments played a mighty role. Adam Michnik has told us that, during the bad old days in communist Poland, the dissidents used to pass around Glucksmann’s writings. In communist Czechoslovakia, Václav Havel was his friend. I have seen with my own eyes that, in Ukraine and in the Republic of Georgia, Glucksmann has continued to be revered into our own moment, and the list of countries could go on. It is also true that he has always had detractors. Glucksmann was America’s most vigorous defender among the modern French intellectuals, and I think that not more than one or two university departments in the United States ever invited him to deliver a lecture. In the American universities, no one has bothered to translate his major writings. The fashion for French philosophers in the American universities has always been a fashion for the wrong philosophers. Then again, the universities in America may not be as central to the intellectual world as they imagine themselves to be.

On the New Yorker website just now, Adam Gopnik recalls whiling away afternoons with Glucksmann in Paris during his time as a magazine correspondent there, and the description makes me reflect that, if the intellectual world does have a center, Glucksmann’s apartment ought to count as one of its locales. I recognize Gopnik’s details: Glucksmann’s purposeful conversation, the combination of a sweet demeanor and a moral firmness, the habit of referring everything to the classics of literature. I can attest that conversation in that apartment could make a powerful impression. My own first knock on the door took place in 1984 because the American political philosopher Dick Howard, who had played a part in the French student revolution of 1968, had talked me into reading Glucksmann. Just then Glucksmann had scandalized the French public and the enormous French left by coming out in favor of Ronald Reagan’s anti-Soviet missiles in Europe, which seemed to me unimaginable. And I talked Mother Jones into sending me to Paris to produce an article, in which I intended to reveal Glucksmann as a deplorable case. I do not have the heart to look at that article today, but I think I did try to suggest that Glucksmann was a fool. Only, by the time the article was in print I had begun to doubt my own evaluation.

The New Yorker writer Jonathan Schell had written a plea for nuclear disarmament titled The Fate of the Earth, in which he made disarmament seem like common sense. And Glucksmann had written a response called The Force of Vertigo, which—though it took me a while to recognize my own response—impressed me. Glucksmann worried about dreamy visions of world peace. Dreamy visions seemed to him a ticket to war. He had a lot to say about the Soviet Union and its own weapons. He argued that, in the face of the Soviet Union, nuclear deterrence and common sense were one and the same. Pessimism was wisdom, in his eyes. He wanted to rally support in the West for the dissidents of the East, which was not the same as staging mass demonstrations against Ronald Reagan. His book was a tour de force of mockery, erudition, spleen, and energy, together with a habit of banging on big philosophical drums from time to time. Reading it made me bug-eyed in wonder. And, when he answered the door and led me into his apartment, I marveled still more.

He had the ability to rephrase his own learned arguments in a tone of everyday conversation, as if to demonstrate that, for all the baroque ornaments in his literary style, his thinking did not depend on ornamentation. He was comfortable with the peregrinations of his own logic, which were his own, and no one else’s. Nor was there any vanity in his reasoning, even if there was vanity in the Latin citations. It is true that he boasted about Sartre’s regard for him, and about his friendship with Foucault. But this kind of vanity is proper to writers. And he had reason to boast. He gave the appearance of being a man trying to summon common sense, on the basis of his own experiences. Also he was happy to speak the language of the left, if that was my preference. No one had a stronger leftwing background than Glucksmann’s, beginning with his parents, heroes of the anti-Nazi Resistance. The leftwing background, by the way, had everything to do with his influence among the dissidents of the East Bloc in those years. The dissidents, most of them, were themselves men and women of the left, sincere Communists in many cases, or the offspring of Communists, who had begun to wonder if, on leftwing grounds, they oughtn’t to revise their estimation of Communism; and Glucksmann was the same, except that he happened to live in France. And France had given him the benefits of a first-rate education.

The apartment seemed to me a cathedral of high ceilings, double-stacked bookcases, paintings (the gifts of artist-friends) that I never had time to examine, magnificent rattan chairs and other creaky furniture, antique molding from some previous century, warrens of corridors lined with still more books, and grand windows opening on the narrow and busy commercial Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière. Somewhere I have read that Oulipo, the avant garde literary movement of the early 1960s, used to meet at Glucksmann’s apartment, but I suppose that must have been a different apartment. He was able to buy the place on Faubourg-Poissonnière only after one of his early books turned out to be a big seller. Still, Oulipo remained on his mind. He advised me more than once to read Raymond Queneau, one of the Oulipo writers—a lasting influence on Glucksmann, I deduce. I wonder if Oulipo volumes didn’t fill some of those massive bookshelves. When I am in a writer’s home, sometimes I wish the writer himself would disappear for a few hours, in order to give me the freedom to go roaming through the bookshelves. Here, surely, must be the secrets of his genius. I want to know how many ancient Greeks there are, and how many Victorians. But I was always in conversation during my visits, either with Glucksmann or with his wife, the fiery Fanfan. Or his son Raphaël was on his way in or out. Other people, too, were always stopping by for a few minutes or for the evening or because they were sleeping in some corner of the apartment—frightened young exiles from Chechnya, a touring Italian politician, the old Trotskyist filmmaker Romain Goupil (who, I read, was with Glucksmann at his death, together with Fanfan and Raphaël), and onward.

The apartment does have a legend of being a center for refugees—Latin Americans fleeing rightwing dictatorships, East Europeans fleeing leftwing dictatorships, East Europeans fleeing Putin’s right-wing dictatorship. One day, at a dinner sometime after Sept. 11, in front of a gigantic cheese the size of a pillow, I discovered that I, and not anyone else, was the visiting refugee, asked by my host to provide a personal recollection of New York and Brooklyn on the day of the attack: Where did I walk? What did I see? What was it like? This was a Glucksmannian moment. You think you are a privileged person? You think you are a citizen of the world’s most powerful country, which will never have to endure the sufferings that other nations are always having to endure? You think that gigantic massacres take place only outside other people’s windows? André Glucksmann begs to remind you otherwise. His eyes burned in my direction. In his autobiography, A Child’s Rage, he recalls that, in the aftermath of the Liberation of France, his mother went to work for an orphanage run by the Rothschilds for Jewish orphans, of whom there were a great many, which meant that he himself spent time at the orphanage. His little friends, the orphans, were skeletal, unstable, and snot-nosed. To be at ease with refugees was his natural condition.

Glucksmann was denounced intermittently throughout his career as a traitor to the left, and I think that, for him, this made for a sometimes difficult experience. His Cook and the Cannibal, from 1975, on the Soviet gulag, was an explicitly left-wing book, which invoked the Black Panthers of the United States (on the topic of prisons) and drew on Foucault (the philosopher of incarceration), and offered, in any case, a passionate defense of the bottom-most oppressed, the prison population of the Soviet Union. It was a book in the tradition of Victor Hugo, surely a bigger influence on him that Oulipo. But the visible spirit of social solidarity in his book did not spare him the wrath of a large portion of the left of those days, who did not care to hear discouraging news about the Soviet Union. On the other hand, after a few years, those particular denunciations came to an end, and a good many people began to reflect that maybe Glucksmann had been right, after all. There was a rhythm to how these transformations in his reputation took place. I have noticed over the decades that, every time I visit certain friends in France, they tell me that Glucksmann in the recent past used to be an admirable thinker, but lately he has become a reactionary and is no longer relevant. And, when I visit the same people a couple of years later, they tell me the same: Until recently he may have been a superb intellectual, but now he has become an irrelevant reactionary. Eventually I figured out that he was merely ahead of his public. People needed a few years to digest what he had to say.

Also he wore his critics down. The critics would denounce him as a man who had lost all sense of ideals and political decency, a notorious ideologue, a sell-out, a self-promoter, and so forth. And Glucksmann would go on, undeterred, leading one campaign after another for populations at extreme risk, the oppressed of the oppressed. His book about prison laborers in the Soviet Union was only the beginning. It was Glucksmann who rallied the French intellectuals to call for aid for the “boat people” of Vietnam—the vast tide of desperate refugees from the Communist victory in South Vietnam. The Bosnians, the Kosovars, the murdered Rwandans, the Chechens whose country was destroyed by Putin—these people were his causes. The AIDS epidemic broke out. He wrote about denial, which was his greatest theme. Marxism is supposed to be a social science designed to see through hypocrisies and denial, but Marxism ended up as a kind of earplug, guaranteed to deafen its disciples. Such was his argument. He made it so powerfully that, all over the world, the political left has never been the same, afterward.

Intellectually speaking, he did not care if old-fashioned leftists of a certain kind accused him of betrayal. His own rebellion was to reject political ideologies altogether. The leftists denounced him as a right-winger, and sometimes the press picked up the cliché, but this, of course, was never accurate. You have only to read two pages by Glucksmann to appreciate that he is not a man of conservative instincts. He is outraged by injustice; he is moved by the despair of the most desperate; he doesn’t give a damn about hallowed traditions. These traits of his were constitutional. His final book is about Voltaire—I wrote about it for Tablet—and, in that book, he mounted a defense of the Roma, or Gypsies, in France, people so downtrodden they have ended up deformed and ugly, doomed to the pathologies of organized crime. In France, to defend the Roma has not been in fashion. But France’s most principled intellectual was on their side.

It is true that, in the French election of 2007, he came out for the conservative candidate for president. This was Nicolas Sarkozy, and Glucksmann’s endorsement aroused the harshest denunciations of his life. He could not walk in the street without being rebuked by the leftwing passersby. As it happened, he came to the conclusion, after a couple of years, that his endorsement was a mistake, which he regretted. Still, it is worth recalling what led him into his mistake. Sarkozy, back in 2007, presented himself as a conservative of an unusual kind—someone who, unlike the conservative candidates of the past, was not of old French stock and who entertained progressive ideas on a variety of matters. He wanted to modernize the economy to solve the chronic unemployment in France. He proposed to build mosques, which was a good idea. He reached out to the political left. If you look at the opening pages of Bernard-Henri Lévy’s book Left in Dark Times you can see a description of just how aggressively Sarkozy went about courting the left—in this instance, with a telephone call to BHL, pleading for his own endorsement. BHL declined.

But Sarkozy made a similar telephone call to Glucksmann, who, instead of saying no, came up with an interesting proposal. Sarkozy had mused about a transformation of French foreign policy away from the old and traditional realpolitik and the leftover habits of French imperialism into something more humanitarian and idealistic. Glucksmann proposed to him that, if he was serious about any of this, he ought to make Bernard Kouchner the foreign minister. Kouchner was a man of Glucksmann’s temper: Someone who, like Glucksmann, had spent his infancy in occupied France, and had grown up in the bosom of the Communist Party, and had turned away from the Communists in favor of human rights and an activist humanitarianism. Only, Kouchner had done this as a medical doctor and a man of action, and not as a philosopher. Kouchner, during the period when he was still a Communist, had been a comrade of Che Guevara’s in Cuba; and, when he turned away from Communism, he became a kind of Che Guevara of medical action. He and a couple of other people had founded Doctors Without Borders to bring their activist humanitarianism into the zones of extreme poverty and suffering in the remotest corners of the world. There was no one Kouchner had not served: The impoverished Guatemalans, the Palestinians, the Kurds, the victims of Africa’s civil wars. Glucksmann’s suggestion to Sarkozy might have sounded a little wild. Kouchner was a Socialist. More: Kouchner was the most popular Socialist in France, according to the polls. The leaders of the Socialist Party were fools not to have made him their own candidate for president. Sarkozy saw an opportunity, though, and he asked Glucksmann to sound out Kouchner.

Glucksmann called. Kouchner was tempted. So, yes, Glucksmann endorsed Sarkozy in the election, which seemed a treason to the political left. Sarkozy went ahead and appointed France’s most admired Socialist as foreign minister. And, at that moment, it became possible to imagine that something new had taken place: a union between the modernizing conservatives, whom Sarkozy represented, and the anti-totalitarian left, whose profoundest thinker was Glucksmann and whose greatest man of action was Kouchner. It became possible to imagine that a new kind of foreign policy might emerge, not just in France—a foreign policy based on Glucksmann’s principles (if not necessarily on Glucksmann’s judgments about this or that situation around the world, which were sometimes hotheaded) and Kouchner’s worldly experience. Certainly the appointment aroused a bit of excitement in the United States.

On the day that President Sarkozy, newly elected, announced that France’s foreign minister would be Bernard Kouchner, Richard Holbrooke telephoned me from somewhere in the world to express his own excitement. I think Holbrooke was in East Africa, working on an AIDS project, or maybe he was in Pakistan, where he used to spend time in order to prepare himself for some future diplomatic post, or maybe he was holed up in the exotic remotes of Washington, D.C.; but, in any case, he needed to get hold of someone who could share his enthusiasm. He exclaimed into the phone: “Bernard!” The name said it all. I suspect that Holbrooke was entertaining the possibility that Hillary Clinton was going to be the Democratic nominee for president in 2008, and, if she won, he was likely to be appointed secretary of state. He and Kouchner were friends, and I think he relished the idea that, if he did become secretary, he and Kouchner would be able to establish a new sort of French-American global diplomacy: Forceful sometimes, humanitarian almost always, based on the idea that rich and powerful nations have a responsibility to the super-oppressed of the world, even if it may be a challenge to come up with policies capable of achieving what needs to be achieved. Holbrooke was thrilled that France, at least, had evidently chosen such a path.

Only, it all turned out to be a delusion. Sarkozy exploited his opening to the left in order to win the election, and he installed Kouchner as foreign minister, and he awarded a medal to Glucksmann and gave him a seat on the presidential plane. He even allowed Kouchner to organize a few beneficial adjustments to France’s policy toward powerless countries in Africa, which made it seem, for a moment, that something new was, in fact, underway. Change was a deception, though. Sarkozy had no intention of allowing Kouchner to run the important policies—above all, France’s policy toward Russia. Sarkozy turned out to be a traditionalist in French foreign affairs, which is to say, a maneuverer for national advantage and even personal advantage. He was not, in reality, a worldwide champion of human rights. He cut a deal with Putin.

Kouchner exited the government, disillusioned, and Glucksmann turned against Sarkozy, embarrassed at having campaigned for the man. Glucksmann’s enemies will never forgive him for his endorsement. They will cite it forever as the sign of his rightward drift, or a sign of personal opportunism—his treason to the left. But it was not a sign of rightward drift, nor was it opportunistic. It was a mistake. It was part of the tragedy of an era in which George W. Bush turned out to be incompetent, and Tony Blair proved to be better at speech-making than at decision-making, and Sarkozy turned out to be no improvement over his predecessor, Jacques Chirac, the champion of French interests, narrowly conceived, not to mention his own interests. Glucksmann was willing, at least, to acknowledge the mistake. BHL has noted just now that a willingness to acknowledge error was part of Glucksmann’s greatness. Glucksmann hit back, too. Sarkozy, being a conservative, denounced the uprisings of May 1968. Glucksmann, being a ’68er, collaborated with his son Raphaël in writing a book defending (mostly) the uprisings to Sarkozy—Raphaël Glucksmann, who is the author just now of his own lively and polemical tract, Génération gueule de bois: manuel de lutte contre les réacs, or (roughly) Hangover Generation: Manual of Struggle against the Reactionary Old Farts, which displays handsomely the family aversion to the old-school bigots of French life and their modern-day apologists.

I worry that, in going on about Glucksmann’s various political books and campaigns and successes and failures, I may have painted him in the gray tones of most other political writers. Something was technicolor about the man. It would be foolish to reduce his thinking to a doctrine or two and a couple of slogans—anti-totalitarianism, a refusal of utopian hopes, the “gospel of bad news,” “the right to D-Day.” In truth, he was—he is—a man of a thousand ideas. His books are of uneven quality, as is always the case with prolific writers, but all of the books are alive with throw-away observations, sardonic wise-cracks, displays of prowess with the knife and the sword, and splendid evocations of lessons to be learned from the authors of classical antiquity or the French 17th century. If Glucksmann had ever been tempted to carve out a career for himself as an academic system-builder, he could have constructed a multi-volume doctrine out of any of a dozen perceptions in the course of those books, and would have ended up as the head of his own “center” at the University of California.

His ideas have absolutely been an influence on my own thinking, such that sometimes I forget that one or another thought of mine may well be a cheerful American adaptation of a respectably gloomy philosophical observation that long ago I stumbled across in some old book of Glucksmann’s. Maybe 20 of those books are sitting on my own bookshelves, with probably two or three others lurking somewhere else. I look on those books as a kind of bank, from which, whenever I am in search of ideas or inspirations, I may make a new withdrawal. Ten years ago I wrote an essay in the New Republic touching on a book of Glucksmann’s called The Discourse of Hatred, where he offers a unified-field theory of three kinds of hatreds, each of them thriving in the modern world—the hatreds that are misogynist, anti-Semitic, and anti-American. Today, when my eye alights upon the book, it occurs to me that I should go through it again because I would certainly come up with inspirations for my own essays. Here is a book called The Most Beautiful History of Liberty, with a preface by Havel, which offers a conversation between Glucksmann, the political writer Nicole Bacharan, and the wonderful essayist Abdelwahab Meddeb, who died a year ago this month—which reminds me that Meddeb, too, deserves an essay. Here is Glucksmann’s The Discourse of War, from 1967, written when he was a deluded Maoist, but which is, even so, a brilliant discussion of guerilla war and its relation to language—a book that could yield a dozen new insights into our present-day counter-jihad, if anyone wanted to scoop up the gems. Here is his book on Heidegger, which I haven’t read; but the prospect of doing so cheers me. A book on Charles de Gaulle: probably I will pass it up, but that might be a mistake. I seem to have misplaced the book that Glucksmann wrote about the Jews with Elena Bonner, the Russian dissident from Soviet times. That book, too, may be worth an essay. It occurs to me that long ago Glucksmann convinced me that I ought to read Seneca’s plays. But I am going to have to stop thinking about these things.

Some years ago, confronting his own mortality, Glucksmann asked me to write his obituary. “I charge you,” he said. I have written a rambling commentary instead. But it is true to the moment. Today, Nov. 13, is the day of his funeral at the Père Lachaise cemetery. Paris is ahead of New York on the clock, and the funeral may have gotten underway even as I am typing.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.