The End of the Affair

In a book on the Dreyfus Affair, writer-lawyer Louis Begley offers a 21st-century J’accuse

As the 19th century was ending, Europe engaged in a series of dress rehearsals for the calamities awaiting it in the 20th. The Dreyfus Affair was the most conspicuous of these portents of the terror and inhumanity to come. The conviction of a French artillery officer of Jewish extraction for a treasonous act committed by another exposed virtually every ailment that threatened the modern state—justice perverted by those charged to uphold it, the institutions of a free society turned against the rights they were designed to preserve, and the explosion of Jew-hatred that would, in a later decade, rally the mediocre to the banner of universal murder.

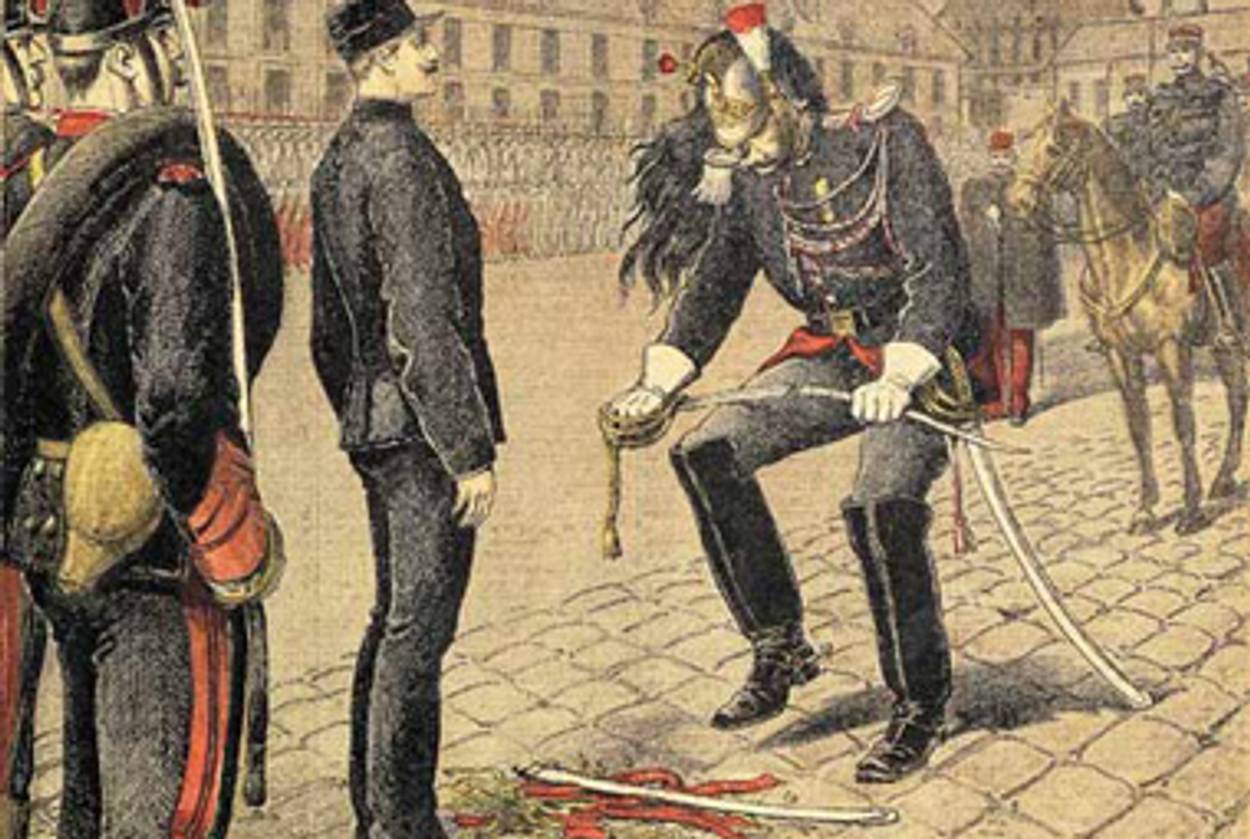

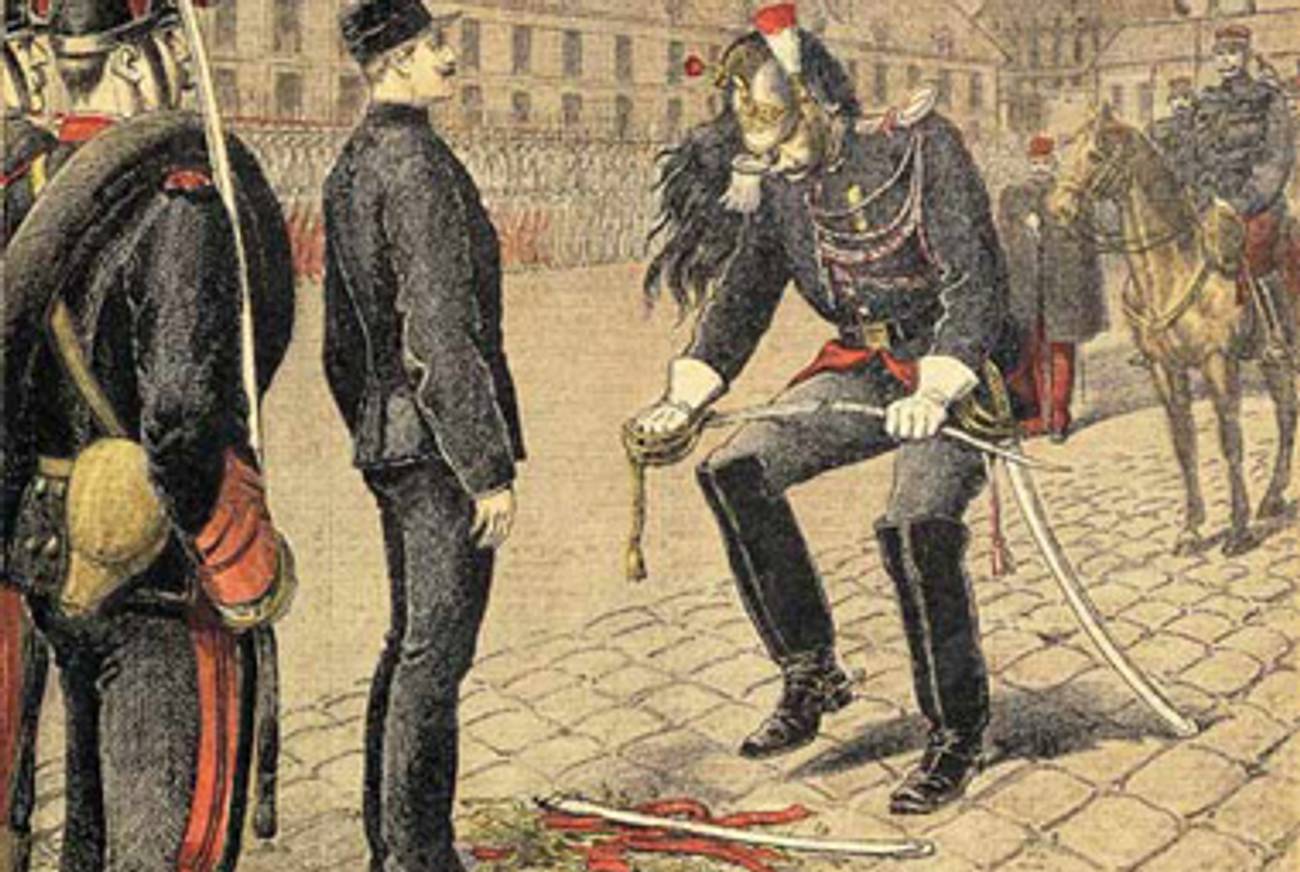

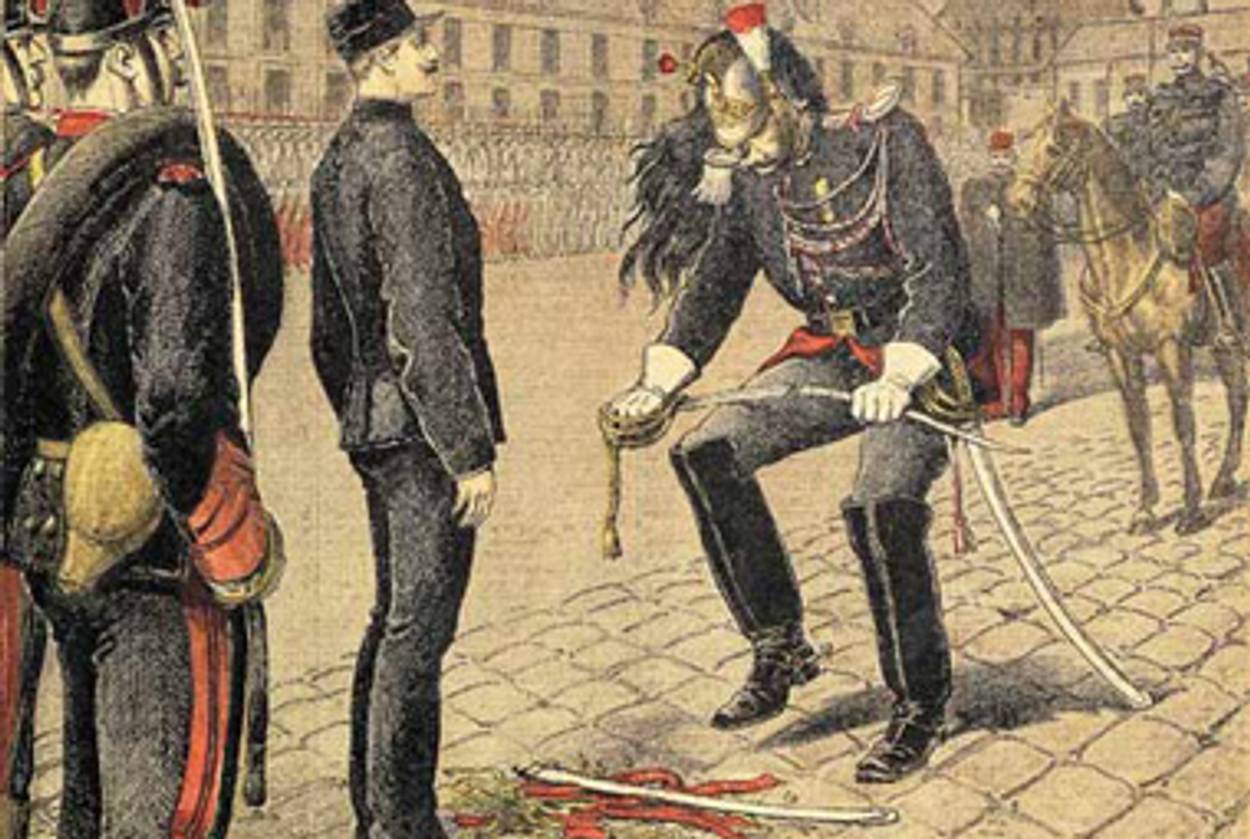

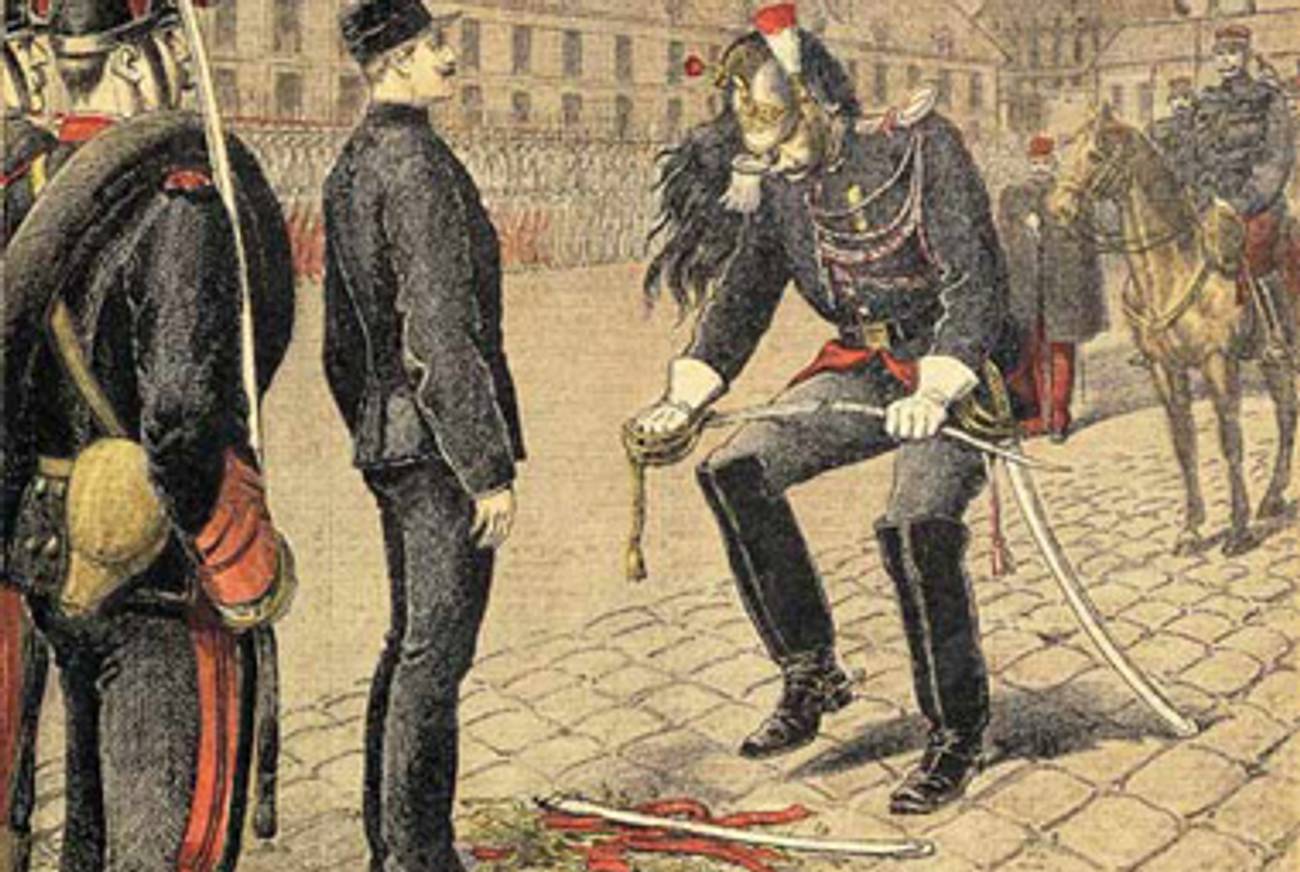

“Death! Death to the Jews!” resounded in the courtyard of the École Militaire as fellow soldiers ripped the decorations off of Captain Alfred Dreyfus’ cap and sleeves, tossed his badges of rank onto the ground, and broke his saber in two. This was during the ceremony of degradation that preceded his internment in the penal colony of Devil’s Island. Dreyfus, a recent graduate of the nation’s elite military academy assigned to the General Staff, had been convicted on the basis of a resemblance, controverted by one of the experts assigned to evaluate it, of a single scrap of his handwriting to that of a document seized by a spy from the German embassy enumerating a list of items (the infamous bordereau, as it came to be known) delivered by a French agent to his German handler. The rest was prejudice, guesswork, and group-think: his accusers were never able to establish any motive (Dreyfus was a devoted family man and the inheritor of a large industrial fortune), and the character testimony adduced against him consisted of the aimless tittle-tattle of resentful classmates assured by their superiors that he was a traitor. The army rallied around documents brazenly altered by one of their agents to buttress a fabricated certainty. These documents were secretly presented to the military jurors who would go on to convict him, in defiance of the most basic courtroom propriety. Overcoming the army’s intransigence and its deceptions would take more than a decade, and a struggle for truth and justice of unprecedented scope.

Present in that crowd of onlookers was the Paris correspondent of Vienna’s largest newspaper, the Neue Freie Presse. Writing five years after the event, that writer, Theodor Herzl, who had in the intervening years recast himself in the role of political visionary, lamented that such an event could occur even “in republican, modern civilized France, one hundred years after the declaration of the Rights of Man.” He discerned in those bloodthirsty chants “the wish of the enormous majority in France to damn a Jew, and, in this one Jew, all Jews,” and concluded that in that call “the edict of the Great Revolution”—which had granted Jews full citizenship rights more than half a century before any other country—“has been revoked.” The implied question was clear—if this is what is done to a Jew in France, what will they scruple to do to him in Austria, Germany, Poland, and the Ukraine?

The call for Jewish blood would resound throughout France in the years to come, inflamed by a rabid right-wing press ascribing all the efforts to secure justice for the condemned to a diabolical “Jewish syndicate.” The syndicate, in the paranoid vision of its antagonists, was composed of Jewish international bankers and all the venal politicians, journalists, Socialists, Republicans, and anti-clericalists whom they had bribed or found common cause alongside in the assault against all that was traditional, decent, honest, God-fearing, virile, and orderly in the French nation.

These were the chauvinist, nationalist, and anti-Semitic notions that would someday metastasize into the mass political movement known as fascism. But the Dreyfus Affair was only a symbolic enactment of the infamies to come. Dreyfus survived his ordeal on Devil’s Island and lived to see his total vindication. The French military that re-convicted Dreyfus in 1899 for a crime that its highest ranking officers knew by then he had not committed awarded him, in 1906, with its highest decoration. The countervailing forces that rallied to Dreyfus’ cause, by the end of the affair, had effected a total rout of their opponents; indeed, this rout was a condition of his vindication.

The Dreyfusard party began as a party of one—Dreyfus’ brother Mathieu. One by one, men of talent and energy were converted to the cause. Among them were the great novelists Anatole France and Émile Zola, who penned, in the wake of a military court martial’s exoneration of the crime’s true culprit—a penniless adventurer and rake named Count Esterhazy—the most consequential work of crusading journalism ever published: the open letter to the French President Felix Faure in defense of Dreyfus that went by the name of J’accuse. The men of science and letters who emerged as a new force in society during the affair—the “intellectuals,” as they were first dubbed by Georges Clemenceau—were joined by a voice that ought to have been decisive. Lt. Col. Georges Picquart, former head of the Statistics Section, found evidence implicating Esterhazy in the course of his investigations. “What do you care if that Jew rots on Devil’s Island?” his superior asked him, pointing out, as Louis Begley puts it in his elegant summary of the affair Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters “that if Picquart did not tell anyone, no one would know.” To which Picquart responded: “What you are saying General, is abominable. I will not in any event take this secret with me to the grave.”

As Dreyfus’ enemies heaped ever greater stakes on the defense of his conviction, so the Dreyfusard cause came to stand for all of the values against which his enemies inveighed—the accountability of the military to civilian rule, the legitimacy of the Republic to represent the nation of France, and a renewed commitment to the French Revolutionary principles of equality before the law. Eventually the Dreyfusards swelled to include the most powerful men in France, who used the affair to assert greater civilian control over the military and to break the independent power of the Catholic Church—whose newspapers had called for the expulsion of the Jews from France.

The story of how a case of petty espionage and skulduggery in the Army came to polarize all of France into two warring camps is among the most copiously documented events in world history. In its labyrinthine complexity and its many novelistic flourishes, it seemed to anticipate, and indeed to provide the template for, all subsequent political scandals, miscarriages of justice, and abuses of government secrecy that followed it. Wherever truth and fairness are sacrificed on the altar of national security, wherever a legal contest expands to become a political or cultural struggle—an echo of the affair resounds.

It is for this reason among the most frequently referenced events of recent history. The trial and execution of the anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti, the nuclear espionage conviction of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the Wen Ho Lee case—even the OJ Simpson trial, have drawn, with varying degrees of plausibility, comparisons to the Dreyfus Affair. The Weekly Standard even had the chutzpah to call the acquittal by the U.S. Senate of Bill Clinton on the charge of high crimes and misdemeanors for perjuring himself on the subject of his sexual dalliances with the White House intern Monica Lewinsky “Our Dreyfus Case.”

In the period after 9/11, one began to hear of new Dreyfus Affairs, linked to the resurgence of anti-Semitism among Arab youth in Europe. The New York Times called the murder of Ilan Halimi —in which French Arab youths kidnapped, tortured, and killed a young French Jew—“today’s Dreyfus Affair,” while The New Republic attached the headline “Dreyfus Affair 2.0” to an account of a story in which a French court had vindicated the charge made by an online media critic that a French television report about the killing of a 12-year old Palestinian refugee by Israeli soldiers had relied on stage footage.

Both of these attempts to channel the legacy of the Dreyfus Affair cast the significance of that event solely as a matter of anti-Semitism and Jewish self-defense. But Jewish self-defense, narrowly construed, was only one of the many aspects of that multifarious event. The Dreyfus Affair awakened Herzl to the need for Jews to answer aggressive nationalism with a self-empowering national movement of their own. But the assault against the Jews was always also an assault against the universal values of the Enlightenment, of which the Jews had been the special beneficiary.

Begley was a successful lawyer at a major New York firm when he published his first novel in 1991, at the age of 57. Wartime Lies was fictionalized account of his own flight from the Nazis, made at the age of seven. In Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters, he acknowledges the faults of the assimilationist creed of Dreyfus’ and Herzl’s day, laments the “tendency of French Jews to minimize the importance of anti-Semitism, remain passive, and avoid speaking out against outrageous behavior,” and deplores the resurgence of anti-Semitism in the Halimi case and other events like it. But he opens his book by drawing a direct parallel between Devil’s Island—where Dreyfus was held in solitary confinement for five years for a crime he did not commit—and Guantanamo Bay.

The choice amounts to an implicit insistence that Jewish self-defense and the defense of the rights of despised minorities everywhere are always one and the same cause, and that any ostensible pursuit of Jewish interests that countenances the violation of due process and Constitutional protections for the accused, or that winks at lawless behavior in our government or intelligence agencies, is a betrayal of the memory of the Dreyfus Affair. Thus Begley’s riveting account of the affair—as clean, poised, and concise as any yet written—is also an intervention in the politics of the moment and a reminder that though the Jews must be for themselves in a time of great tension and danger, they must not be for themselves alone.

Begley begins his case in the most confrontational way possible, with an act of empathy that many Americans will be reluctant to undertake. He begins by hailing the Obama Administration’s decisions to end “an era of dragnet detentions and mistreatment or worse of alleged enemy combatants, and secret CIA prisons,” and to “bring the United States back under the rule of law.”

“One supposes that the news of Senator Obama’s victory on November 4, 2008, must spread from cell to cell in Guantanamo—except perhaps to those in which detainees, some of them shackled, are held in solitary confinement—and one can imagine the stirring of hope among the prisoners. One can even more easily imagine the joy with which the news of the stay of the trials before the military commission has been greeted.”

Here Begley is extolling the effect of Obama’s election on the morale of Guantanamo inmates. One reflexively imagines—as the writers of the Dreyfus’ time must have had to wonder about the next broadside from La Libre Parole, the scurrilous anti-Semitic newspaper owned by Edouard Drumont, author of La France Juivie—what our scurrilous American right-wing press will make of such an utterance. But though the invitation to empathy seems politically impermissible in the current environment, Begley insists that it is precisely in our reluctance to extend empathy to the enemy combatants imprisoned in Guantanamo that we most resemble the French public that turned its back on Dreyfus. “Just as at the outset of the Dreyfus Affair the French found it easy to believe that Dreyfus must be a traitor because he was a Jew, many Americans have had no trouble believing that the detainees of Guantanamo—and those held in CIA jails—were terrorists simply because they were Muslims.”

There were 800 detainees in Guantanamo Bay in 2001. The claim made by Donald Rumsfeld that they were “the worst of the worst” has been decisively rebuked by the subsequent release of 600 of them without trial or charge by the Bush Administration. Most of them really were just bumbling nobodies who happened to get in the way of the wrong venal US allied warlord after 9/11. But some of them—particularly the “high level detainees” in CIA jails—have the blood of thousands of American innocents on their hands. Not that Begley doesn’t know this, but it bears repeating simply because of a structural problem built into the analogy between “inmates of American detention during the War on Terror”—a category encompassing hundreds of the guilty and not guilty—and “Dreyfus”—one innocent man—can lend itself to a certain misleading equivalence that Begley, in his zeal to make his argument, does not always avoid.

These minor reservations aside, Begley has written a brave and important book. Beneath its lawyerly precision, the book vibrates with what one feels must be a personal passion. Begley fled a Europe destroyed by hate and fear, a world in which the dread of enemies without and within led an ancient and civilized nation to imprison, torture, and kill without restraint, and to wage a war without limits while husbanding an intact sense of its own righteousness and victimization through it all. He found in America a virtuous haven for himself and others of his kind which permitted him to join the ranks of its wealthy elite in a single lifetime—only to observe, in old age, the lawless depredations of the Bush Administration in the wake of 9/11. “As each generation confronts the outrages committed in its name,” he writes, permitting his lawyerly voice to lift toward eloquence, “analogies to past outrages become clear, illuminating. And so does the need for a response to the question that has been posed time and again without losing its urgency: Will there be in that generation men and women ready to defend human rights, and the dignity of every human life against abuse wrapped in claims of expediency and reasons of state?”

The Dreyfusards answered the call in their own time. The answering voices confronting malign forces in the time of Begley’s childhood were not sufficient to the task posed to them.

Of our own time, Begley writes:

“Journalists dedicated to exposing the abuses of the Bush Administration, members of the federal judiciary unflinchingly upholding the rule of law, military lawyers who have put their careers at risk by taking a stand against torture and kangaroo trials, and civilian lawyers and law professors of all ages who have devoted thousands of hours without pay as legal defenders of Guantanamo detainees have given the answer for the United States. They have redeemed the honor of the nation.”

Wesley Yang is the author of The Souls of Yellow Folk.

Wesley Yang is the author of The Souls of Yellow Folk.