The Forgotten Confederate Jew

How history lost Judah P. Benjamin, the most prominent American Jew of the 19th century

Temptations is a New Orleans strip joint whose neon sign declares it “The Gentlemens’ [sic] Club in a Class By Itself.” Open noon ’til dawn, it sits on a crowded stretch of Bourbon Street between the century-old Galatoire’s restaurant and Larry Flynt’s Barely Legal Club. Inside Temptations, the ground-floor parlor is done up in antebellum-period décor, with a pair of grand fireplaces and crystal chandeliers. The paint on the walls cracks with antiquarian charm. At the rear of the room, red velvet-upholstered stools line a bar that serves up chilled cocktails to cut the bayou heat. The parlor is centered around a stage with a dance pole, where, during a recent late-night visit, a stripper billed as “Ryan” Lockhart was hard at work, wriggling her g-string-clad body around the head of a bald man with a fist full of money.

When Lockhart finished her routine, redonning her leopard-print brassiere and shredded black dress and joining the half-dozen other ladies working the floor, I asked if she was aware of the building’s notable history as the former home of Judah P. Benjamin, the Confederate secretary of state and America’s first openly Jewish senator. She was not. I told her that up the staircase to the lap-dance rooms had once ascended “the brains of the Confederacy,” the U.S. Senate’s whip-smart “Gentleman from Louisiana,” a gifted orator—the most prominent American Jew of the 19th century.

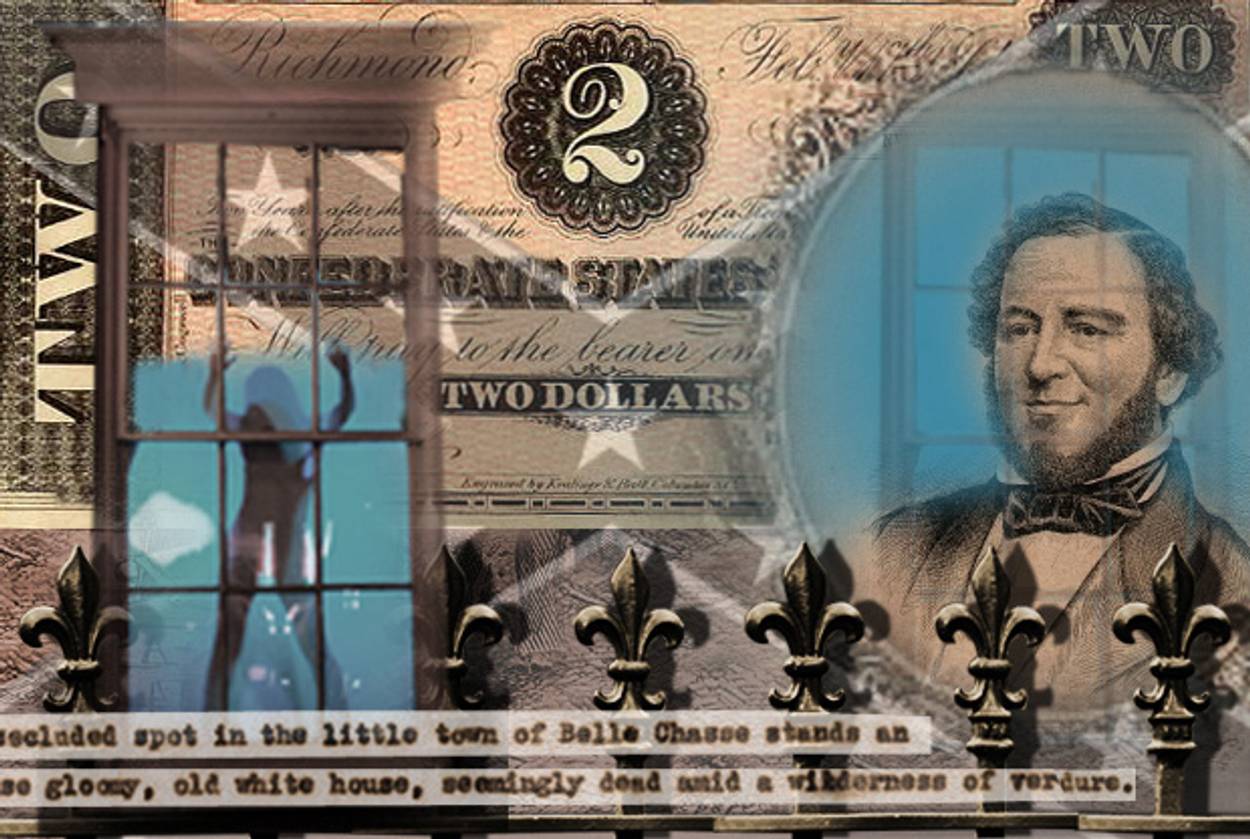

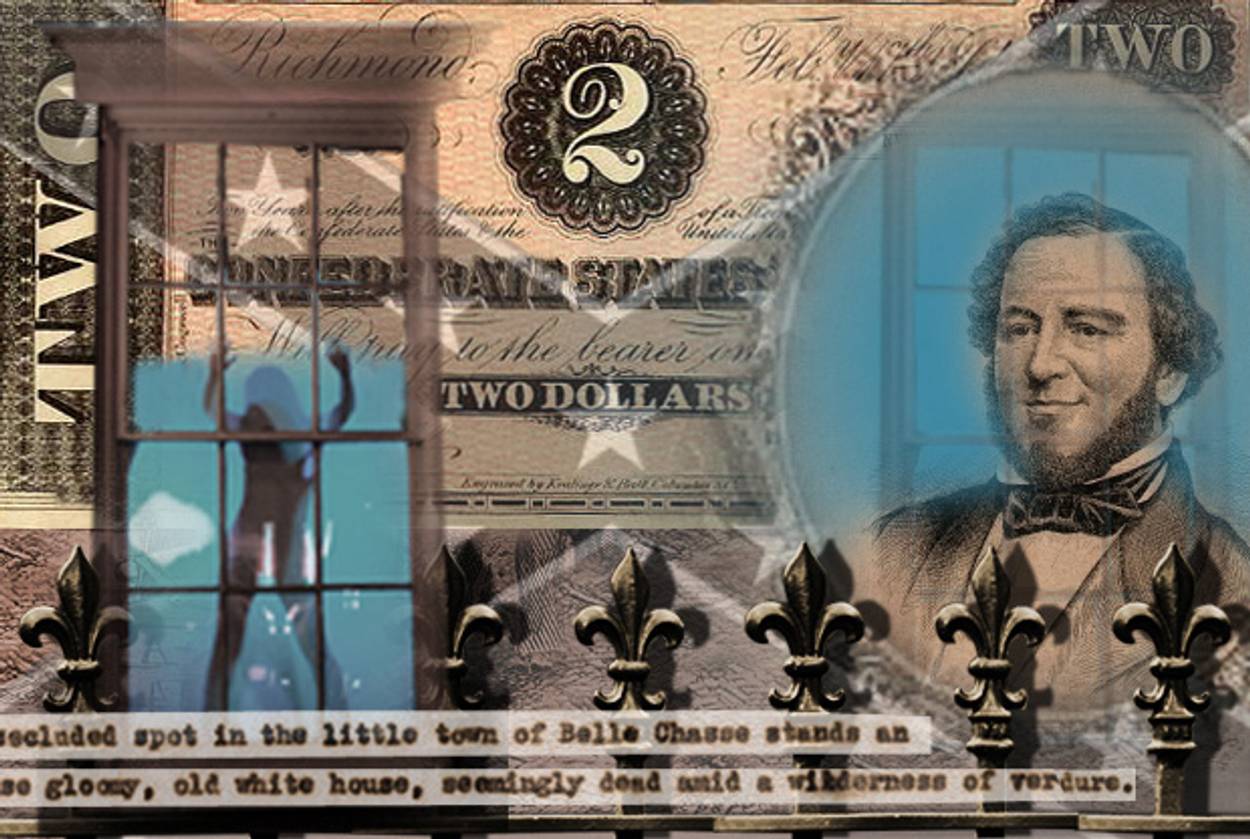

Lockhart’s ignorance was unsurprising—and not just because the exotic dancer is no Civil War buff. Benjamin has confounded even the myriad professional historians who have tried to rescue him from his obscurity as the enigma who stares out from the Confederate $2 bill. But how could so prominent a man, anointed in the moonlight-and-magnolias-besotted chronicle of the antebellum Southern aristocracy, A Class by Themselves, as “arguably the greatest of all Southerners,” be so utterly forgotten today?Temptations, I pointed out, didn’t have so much as a plaque acknowledging its building’s tremendous significance to New Orleans, Southern, and American-Jewish history.

Lockhart, having mastered her profession’s art of feigning interest in men’s minds as a way into their wallets, pressed her hand insistently to my thigh and gushed, “That explains why the place is haunted.”

***

Benjamin hovers like an apparition over American Jewish history. His four-story Bourbon St. townhome was erected in 1835 for him and his new bride, Natalie St. Martin, and his in-laws, French colonial aristocrats who had fled the Haitian slave revolt of 1791 for New Orleans. Benjamin had married Natalie two years earlier, when he was 21 and she just 16.

Benjamin was born a British subject on St. Croix in 1811 to a family of Sephardic Jews. In 1822, the Benjamin family immigrated to America, seeking their fortune in what was then the nation’s most Jewish city: Charleston, S.C. According to S.I. Nieman’s 1963 biography—one of a string of such scholarly tomes collecting dust on library shelves—the boy who would grow up to be one of the South’s leading defenders of its peculiar institution was welcomed to the famously beautiful port city with the grisly sight of dozens of limp black bodies dangling from gallows. A few days before the Benjamins’ arrival, sentences had been meted out in a slave revolt conspiracy organized by Denmark Vesey, a Haitian-born freedman who had hit the Charleston city lottery and, inspired by the revolution in his homeland, used his winnings to finance an ill-fated slave uprising.

As a Charleston schoolboy, Judah was adored by his teachers for his quick mind. He was packed off to Yale at age 14 where he became the sole Jew in his class. In New Haven, Judah distinguished himself as a debater, engaging the questions that he would eventually argue on the Senate floor, including “Ought the government of the U. States to take immediate measures for the Manumission of the slaves of our country?” and, ominously, “Is it probable that our country will continue united under its present form of government for a century?”

But the little big man on campus—Benjamin stood just over five feet tall—never graduated. In 1827, he was expelled from the university for “ungentlemanly conduct” of an unspecified nature. Rumors that the tempest in New Haven involved gambling, carousing, or kleptomania dogged him the rest of his life, particularly during the Civil War when the Northern press rehashed the scandal to tar the man they called the South’s “evil genius.”

Benjamin hovers like an apparition over American Jewish history.

Apparently ashamed to return to Charleston in disgrace, Benjamin instead headed to its bawdy sister city on the Mississippi: New Orleans, a polyglot metropolis of 50,000 divided by its central artery, Canal Street, into francophone and anglophone zones. Perhaps inspired by their own sleepless nights letting loose on Bourbon Street after a long day at the archives, myriad historians have indulged in evidence-free speculations on the debauched Big Easy antics of the young Benjamin. “Whether he also found time for the ladies and the music of Rampart Street, for the fiestas and the street dancing, no record would show,” Nieman wrote. “But for a few short years, he was a gay bachelor, and New Orleans was ‘the City of Sin.’ ” In today’s post-Stonewall hindsight, however, the scant historical record would suggest that Benjamin was, if anything, a gay bachelor in the contemporary sense of the word. Yet this doesn’t stop another biographer from speculating that Benjamin may have fathered children with a mixed-race mistress, as was common among upper-class gentlemen in antebellum New Orleans. (In these common-law marriages, the children took the father’s name, which strongly suggests that Benjamin did not engage in such heterosexual, hetero-racial liaisons.)

If Benjamin was gay, he soon had a beard. A generation after Louisiana’s acquisition by America, the territory’s French Creole elite was eager to marry its daughters off to the ascendant Americains and Benjamin, eager to move up in his latest hometown, learned French, began tutoring Natalie St. Martin in English as a second language, and married her in 1833. (He remained Jewish and she Catholic in a remarkably modern arrangement.) It was a marriage of convenience. Judah got the social legitimacy that helped him build his career first as a corporate lawyer and then as a politician as well as netting him a sizable dowry that included a pair of slaves. Natalie married a successful attorney on his way to becoming a leading statesman, a man who asked little of her in return. Natalie soon abandoned both the Bourbon St. townhouse and the whitewashed Greek Revival plantation home Benjamin built downriver in Plaquemines Parish, for the cultured life of Paris—and the attentions of a string of other men. Despite her open infidelity, Benjamin continued to support his wife’s lavish lifestyle and arrived annually to visit her and Ninette, the daughter she bore soon after the move to France.

Benjamin’s professional life was as successful as his personal life was troubled. By 1852, “the Little Jew from New Orleans” had made enough of a name for himself as a state legislator to be sent to the U.S. Senate, chosen, as was thencustomary, not by popular election but by statehouse pols. On the Senate floor, Benjamin flourished as an orator of the Southern cause, a master of the secessionist rhetoric that cast slaveholders as victims. After Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, with the war looming, Benjamin intoned in a speech to his Northern Senate colleagues, “You may carry desolation into our peaceful land, and with torch and fire you may set our cities in flames … but you never can subjugate us; you never can convert the free sons of the soil into vassals, paying tribute to your power; and you never, never can degrade them to the level of an inferior and servile race. Never! Never!” When an abolitionist senator, citing the Book of Exodus, called Benjamin out for the signal hypocrisy of a Jew shilling for slavery—he tarred him as “an Israelite with Egyptian principles”—Benjamin cried anti-Semitism and refused to answer the charge on the merits.

With Louisiana’s secession from the Union in 1861, Benjamin, having turned down the chance to be the first Jew nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court, was tapped by Confederate President Jefferson Davis as his right-hand man. During the war, Benjamin rotated through a series of Cabinet positions, first attorney general, then secretary of war, and finally secretary of state. Because of Benjamin’s Jewishness, Davis presumably figured he could never challenge him for the presidency should the South succeed in its bid for independence. (Unlike the United States Constitution, the Confederate Constitution permitted immigrants to become president provided they were Confederate citizens at the time of its ratification.) Secretary of State Benjamin was given the daunting diplomatic task of trying to obtain international recognition for the South as an independent country—a hopeless endeavor he pursued with such zeal he was later dubbed the “Confederate Kissinger.”

When the war ended, Benjamin fled Richmond posing as a French farmer who spoke only broken English. The short, fat attorney eluded a U.S. Army manhunt through the swamps of Florida before setting sail for London, where he began his legal practice anew from scratch. Soon counted among Britain’s most successful barristers, he built his wife a trophy home on the Rue d’Iéna in Paris and threw a lavish wedding for his daughter. In 1884, Benjamin died a wealthy man. Against his wishes, his wife had him buried in a Catholic cemetery, the famed Père Lachaise, where he rests today in obscurity, ignored by tourists tramping from Marcel Proust’s grave to Jim Morrison’s.

***

Why did Benjamin disappear? It is certainly not for lack of scholarly efforts to remember the “Jewish Confederate.” In every age, a heroic sage struggles to rescue Benjamin from obscurity—and invariably fails. The complete catalog of Benjamin biographies reads like a very long joke, a string of titles that includes Martin Rywell’s 1948 tome, Judah Benjamin: Unsung Rebel Prince and then, 15 years later, Nieman’s Judah Benjamin: Mystery Man of the Confederacy. That 1963 work opens by mourning that Benjamin remains “a half-forgotten name,” eerily echoing Rollin Osterweis’ 1933 biography Judah P. Benjamin: Statesman of the Lost Cause, whose preface notes, “Every American thrills at the brave tales of the Day of the Confederacy. And when he recalls the spirit of Calhoun, borne onward by the Sword of Robert E. Lee, let him not forget the indomitable Benjamin, gallant statesman of the Lost Cause.”

Anti-Semitism is undoubtedly a factor in the postbellum’s South exclusion of Benjamin from its Confederate pantheon. The portly, pint-sized Jew commanding the valiant gentile generals was a convenient scapegoat for the military disasters that unfolded on hiswatch as secretary of war. But it is more the events and memorializations of the postbellum era that sealed Benjamin’s sorry fate. While Jefferson Davis became a martyr to the Lost Cause, spending two years in a U.S. Army brig and being stripped of his American citizenship, Benjamin fled the country to become a rich British lawyer. As a resentful, defeated South transformed Southern-ness into a veritable ethnicity—when Jefferson Davis’ daughter, Winnie, was betrothed to a New Yorker, the proposed “mixed marriage” so scandalized the South that the engagement was called off—the Caribbean-born Jew with the francophone Catholic wife did not fit the hero’s casting call.

Even New Orleans’ Confederate Memorial Hall—a monument to the Lost Cause, opened in 1891 and built to look like a church, with its vaulted ceiling and stained-glass—contains virtually nothing relating to the highest-ranking Confederate official the city produced. I was told the institution held a bed rumored to have belonged to Benjamin, but it is kept in storage, disassembled.

For the guardians of Confederate memory after Reconstruction, Benjamin became a kind of pet Jew, generally ignored, but then trotted out at opportune moments to defend the segregated South against charges of bigotry. In 1943, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, an organization whose idea of a fundraiser in the early 20th century was selling primers on the glories of the Ku Klux Klan to schoolchildren, erected a pink granite monument to Benjamin on the Sarasota, Fla., plantation where he set sail to escape his U.S. Army pursuers. As the segregated units of America’s Jim Crow army marched into battle against Hitler’s Jew-hunting Wehrmacht, a UDC official intoned, “While Hitlerites spew lies that tend to arouse anti-Jewish passions … Florida, through the United Daughters of the Confederacy, does well to build this monument … for it will stand as a guidepost and reminder that this nation is still the pillar of freedom and tolerance. It is the south’s personal challenge to Nazism and hate.”

On June 2, 1968, as local headlines detailed a synagogue bombing in neighboring Mississippi by white supremacist night riders, a memorial bell dedicated to Benjamin was unveiled at the site of his plantation home in Plaquemines Parish. Benjamin’s home itself had been leveled eight years before the ceremony to make way for an airfield, despite the Works Progress Administration having pleaded in the 1930s that “No home in Louisiana has more claim to historical interest than this … immense gloomy, old white house, seemingly dead amid a wilderness of verdure.” (The caption beneath the photograph of the just-unveiled memorial in the Times-Picayune makes the suspicious error of identifying Benjamin as “the Confederacy’s treasurer.”)

Southern conservatives were not alone in their discomfort with Judah P. Benjamin. Today’s liberal American Jewish community also appears to be squeamish about preserving the memory of its illustrious ancestor. Reform Rabbi Daniel Polish surely spoke for many when he recounted in the Los Angeles Times in 1988 that learning of Benjamin “represent[ed] a significant dilemma [in] my years growing up as a Jew both proud of his people and with an intense commitment to the ideals of liberalism and human solidarity that I found embodied in the civil rights movement.” In her 2009 Jewish Civil War spy novel, All Other Nights, novelist Dara Horn casts Benjamin unsurprisingly as an arch-villain. Horn introduces him to readers at a painfully ironic New Orleans Passover Seder prepared and served by slaves.

Even if they could make peace with his politics, contemporary liberals still couldn’t claim Benjamin as gay ground-breaker with full assurance because the historical record is too sparse. When a biographer approached Benjamin in the final year of his life, hoping to read his papers and interview him, he replied, “I have no materials available for your purpose. … I have never kept a diary or retained a copy of a letter written by me … for I have read so many American biographies which reflected only the passions and prejudices of their writers, that I do not want to leave behind me letters and documents to be used in such a work about myself.” Before his death, Benjamin destroyed even the few papers he had. (Whatever the facts of Benjamin’s personal life, the title of first gay senator would still likely belong to William King of Alabama, who went to Washington decades before Benjamin and served as a kind of First Gentleman to bachelor president James Buchanan.)

Acknowledging the likelihood that Benjamin was gay makes the pathological privacy that puzzled his chroniclers much more understandable. Reading those biographies today, one experiences the strange sensation that historians are presenting him as an almost farcically stereotypical gay man and yet wear such impervious heteronormative blinders that they themselves know not what they write. At the turn of the last century, one biographer, Pierce Butler, painted Benjamin as a fastidious wedding planner, noting that his letter recounting his daughter’s Parisian nuptials is “almost feminine in its attention to detail.” A 1960s biographer reprints “the dapper Jew’s” queeny rant over the powdered-wig getup he was made to don as a London barrister—and yet insistently paints Benjamin as a hen-pecked, jilted spouse, who reluctantly lived with his little sister, Peninah (“Penny”), rather than his beloved wife at his Belle Chasse mansion. Even as late as the 1980s, a biographer’s dish that Benjamin was “a favorite of all government wives in the Richmond capital” seems to assume his popularity was that of a rake not a hag-magnet.

Only in the 2001 reprint of a 1943 biography does historian William C. Davis finally acknowledge in his introduction “cloaked suggestions that he [Benjamin] was a homosexual.” This distinct possibility colors not only Benjamin’s enduring marriage to an unfaithful woman on another continent but also his mystery-shrouded dismissal from Yale for “ungentlemanly conduct.” In a larger sense, it colors Benjamin’s scrupulous privacy and his descent into historical obscurity itself.

Whatever his reasons, by destroying his papers, Benjamin ensured not just his personal privacy but his historical marginalization. For all his prominence, he is largely absent from Civil War history books because he left nothing for historians to work from. By contrast, such books are dominated by minor personages like Mary Chestnut, the wife of a military aide to Jefferson Davis, and George Templeton Strong, a New York lawyer, not because they enjoyed anything rivaling Benjamin’s importance but solely because they were such committed and eloquent diarists.

***

During the 2010 Jewish Federations of North America General Assembly in New Orleans, four men, a rabbi among them, dropped by Temptations one afternoon and requested a tour.

“The Jewish aspect, that was their interest,” Denise Chatellier, the blonde, middle-aged manager told me, in her office marked “Satan Place.” As word spread through the convention, dozens of attendees slipped out of dull conference sessions to take in the Benjamin residence. “All of a sudden, I was giving all these tours,” Chatellier said. “They were the ones who opened my eyes up to appreciate the whole history of the place.” At the convention, meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu used Benjamin’s signature rhetorical tactic to tar his young Jewish hecklers as anti-Semitic dupes for suggesting that a unique history of suffering should make Jews particularly sensitive to human rights.

On the floor of Temptations, such heady concerns felt remote. As Lockhart’s successor on the pole spun around in a pink teddy, patrons downed enough liquor to blot out whatever would happen in this house a few hours from now, let alone a few centuries ago. Lockhart had told me that the upper floors of the home are inhabited by a ghostly woman in a white dress, whose presence can be felt moving through the darkened hallways and empty lap-dance rooms. She agreed it would have to be Ninette, Benjamin’s Parisian-raised daughter, still searching for her absentee father, a man lost to history not least because he doesn’t want to be found.

Daniel Brook, a New Orleans-based journalist, is the author of two books, includingA History of Future Cities, to be published by W. W. Norton in 2013.