The Jewish Brando

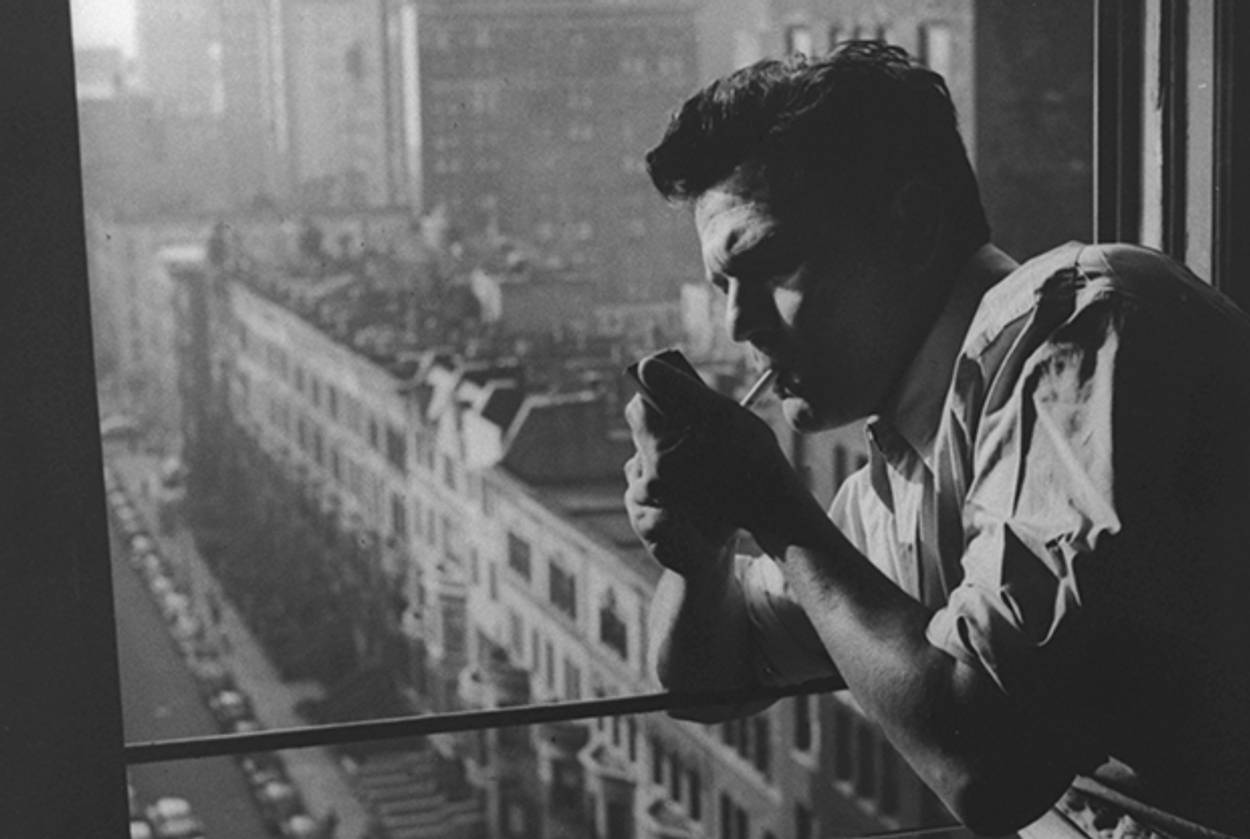

John Garfield, the tough, underrated Hollywood star who would have turned 100 today, embodied Jewish pride

A half dozen years ago, while teaching a college class called “Jews & American Cinema: Outsiders In or Insiders Out?”, I asked each student to name the Jewish-American media figure they thought most prominent. Woody Allen got the most votes. The rest of the nominees were virtually all comedians (Larry David, Sarah Silverman, Milton Berle). Only one action star was cited (Kirk Douglas). No one was familiar with that week’s subject for discussion: John Garfield, the son of an immigrant clothes-presser, born Jacob Garfinkle in a Lower East Side tenement, 100 years ago, on March 4.

A tough, working-class kid who ran with gangs and was repeatedly expelled from school, young Garfinkle tried his hand at boxing, fell into acting (helped at one point by Yiddish stage star Jacob Ben-Ami), and found a home with the Depression radicals of the Group Theater. Passed over for the title role in Clifford Odets’ Golden Boy, he was among the first members of the Group to make it to Hollywood, signing with Warner Bros. in the late 1930s. Although the studio changed his name and he would not play a specifically Jewish character until Gentleman’s Agreement in 1947, he received extensive coverage in the Jewish press. Jewish audiences recognized Garfield as their first Hollywood leading man. Hollywood recognized that, given his emotional volatility, rapid-fire sarcasm, and confrontational sexual charisma, Garfield was a new sort of screen presence—a Brando before Brando.

Indeed, Garfield’s old Group Theater comrade Elia Kazan, who directed Garfield in Gentleman’s Agreement, had wanted him for the role of Stanley Kowalski in the original 1947 production of A Streetcar Named Desire. Had Garfield returned to the stage it would have changed showbiz history; however, Garfield had by then formed his own production company, an outfit largely staffed by like-minded, socially conscious leftists, many with backgrounds similar to his own. The prolonged congressional investigation into alleged communist influence in the movie industry, a period marked by blacklisting and hearings, likely contributed to the tightly wound star’s death by heart attack at age 39.

***

Garfield’s Enterprise (as his company was called) was short-lived and foredoomed. Still, it produced the two best movies he ever made—the boxing drama Body and Soul (1947), directed by Robert Rossen from Abraham Polonsky’s script; and numbers-racket noir Force of Evil (1948), which Polonsky co-wrote, with novelist Ira Wolfert, and also directed. Both of these tense, urban dramas feature Garfield as a Jewish street kid made good (and bad), a prize-fighter and a mob lawyer respectively; both have been newly released on Blu-Ray by OliveFilms in excellent transfers.

In Body and Soul, Garfield’s Charlie Davis turns his back on his working-class background—ignoring his mother’s plea that he “fight for something” not just money or fame. In the movie’s key scene, Charlie, now middleweight champion, stands on the brink of total corruption. He’s controlled by gangsters who have instructed him to throw the biggest fight of his career. At the same time he just reconciled with his fiancée (Lilli Palmer). They are visiting Charlie’s mother in her Lower East Side tenement when a delivery of groceries arrives. The admiring deliveryman is not just a fan who tells Charlie that the “whole neighborhood” is betting on him to win his next fight, but the personification of Charlie’s conscience; he praises America as the land of justice and opportunity where, despite the Nazi terror in Europe, a Jew can be champion. It’s a moment that spells out the fighter’s significance for his people—and perhaps Garfield’s as well.

Inspired in part by the story of boxer Barney Ross (as well as the plot of Golden Boy), Body and Soul was the most Jewish movie made in Hollywood since the 1927 version of The Jazz Singer. (Garfield not only played an explicitly Jewish character but had, as his love interest, a German-Jewish refugee.) Body and Soul is also very likely the reddest Hollywood movie ever. Communist Party members or associates included the director, the screenwriter, and the producer (Bob Roberts), as well as a much of the cast: Anne Revere (Charlie’s mother), Lloyd Gough (Charlie’s “owner”), Canada Lee (Charlie’s adversary and sparring partner), Art Smith (Charlie’s father), and Shimen Ruskin (the delivery man and, like Art Smith, a Group Theater graduate). Most would be blacklisted. Well before its release in late 1947, Body and Soul was being promoted by the Daily Worker and investigated by the government. (FBI files not only identify Rossen and Revere as Communists but complain that the movie’s portrayal of the corrupt fight promoter was putting “the rich and successful man in a bad light.”)

Body and Soul was a critical success. (Bosley Crowther ended his New York Times review by declaring, “Altogether this Enterprise picture rolls up a round-by-round triumph on points until it comes through with a climactic knockout that hits the all-time high in throat-catching fight films.”) It was also a commercial hit that proved to be domestic distributor United Artists’ top money-maker of 1947. The movie was nominated for three Oscars—including actor and original screenplay—won one, for film editing, and made possible a more radical follow-up, Force of Evil.

In Force of Evil, Garfield plays another poor kid who has risen up from Manhattan’s mean streets. Joe Morse is a slick, ambitious lawyer who implements a fix that will allow his criminal boss to consolidate his gambling racket by driving small numbers banks out of business. One of these banks is run out of a Lower East Side tenement by Morse’s delusional older brother Leo (Thomas Gomez), who is set up and killed.

An obvious art film, Force of Evil (which was voted into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 1994) was made with a surplus of shadows and a surfeit of colorful characters and is completely unambiguous in its insistence on capitalism as crime. (“Waddaya mean gangsters—it’s business,” one enforcer whines, nearly a quarter century before The Godfather.) The opening line “This is Wall Street” hangs over the dealings. Much of the action is overshadowed by the skyscrapers of New York’s financial district, while Leo’s neighborhood bank suggests nothing so much as a Ma and Pa candy store or a struggling dress factory.

Polonsky set his story during the Depression to provide motivations for the honest characters involved in the racket; most likely to placate the Breen office censors, he concocted a framing narrative. The narrative would unfold in flashback with Joe Morse giving testimony in the state rackets probe. Unavoidably recalling the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings of the previous year (and eerily anticipating the star’s own fate), the device was dropped in favor of Garfield’s voice-over explanation when the movie reached theaters in late 1948.

By then, Force of Evil lost approximately 20 minutes when Garfield’s failing studio sold the movie to MGM, which then released it as a B feature. Body and Soul, by contrast, was shortened by less than 10 seconds, but that small cut to the body cost the movie much of its soul, and thereby hangs a tale.

A few years ago, Annette Insdorf, Columbia professor and the author of Indelible Shadows, the first history of film and the Holocaust, forwarded me an email she had received from Chicago Police Officer Maurice Richards, regarding an apparent cut in the DVD he had recently purchased of Body and Soul. “It isn’t the money, it’s his way of showing,” the delivery man says when Charlie guiltily advises him that betting is foolish. The next 20 words—“In Europe, the Nazis are killing people like us just because of their religion. But here, Charlie Davis is champion”—are gone, leaving only his final statement, “and we are proud.”

The omission, Lt. Richards wrote, is “disgraceful, outrageous and deliberate. The anti-Nazi content and speaking out against the Holocaust has been purposefully removed from the film. New generations of viewers will never be able to see and appreciate the true legacy of this great work of art and Jewish heritage.” He further called for a “thorough investigation” of the deletion: “It is important to find out when, by whom, and if possible, why this was done.”

Prof. Insdorf made a number of inquiries on the lieutenant’s behalf. (I was one person she contacted and was able to ascertain that the change was not made for TV—the 16mm television print did have the missing 20 words.) Eventually, Patricia Hanson, of the American Film Institute, figured out that Republic Pictures Home Video had released two VHS versions of Body and Soul; the 1986 version included the complete dialogue while a 1992 “45th anniversary edition” (advertised as “digitally remastered from the original”) did not and was identical to the Artisan Home Entertainment DVD purchased by Lt. Richards. “Because of various controversies surrounding the film,” she noted, “it is very likely that the cut was made on the master decades ago.”

The most reasonable explanation for the cut was given to me by Dave Kehr, the extremely knowledgeable film critic who writes a weekly DVD column for the Sunday New York Times. The 1992 version was likely remastered from an export negative. Pointing out that a small studio like Enterprise had no overseas distribution, he theorized that whoever had licensed the movie from Enterprise in the late ’40s cut their negative out of deference to the West German market. No Jews, no Nazis, no Holocaust, no offense. In any case, the OliveFilms Blu-Ray, evidently made from the Enterprise negative, is complete, and the meaning of the movie as an expression of Jewish pride and solidarity—and Garfield’s significance as its embodiment—has been made whole.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

J. Hoberman, the former longtime Village Voice film critic, is a monthly film columnist for Tablet Magazine. He is the author, co-author or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.

J. Hoberman was the longtime Village Voice film critic. He is the author, co-author, or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.