The Jewish Jesus Story

In the mysterious and controversial ancient Hebrew text ‘Toledot Yeshu,’ a counterlife of the Nazarene ‘bastard, son of a menstruant’ that criticizes Jews as much as Christians

Toledot Yeshu (The Life Story of Jesus) is almost certainly one of the most mysterious and controversial, yet exceedingly popular, books in the history of Hebrew literature. The book lays out for the reader the New Testament stories about the life of Jesus of Nazareth from a Jewish point of view. The Virgin Birth, the divinity and messiahship of Jesus, the betrayal by Judas Iscariot, the sentencing of Jesus before the Sanhedrin, his death, and his resurrection as Son of God are all replaced by a newly shaped narrative, what the late historian Amos Funkenstein termed “counterhistory,” that crudely derides the deepest principles of the Christian faith.

Toledot Yeshu was printed numerous times from the beginning of the modern period, in which it became disseminated throughout the Jewish communities both in Islamic lands and in Christian Europe. This attests to the great popularity it enjoyed among Jewish readers. Given such literary success, it is quite surprising that its time and place of composition are shrouded in mystery, as are the historical and social circumstances that gave rise to such a complex and fascinating literary creation. I am not aware of any other work of Jewish culture that has generated such diametrically opposed opinions among scholars. Dating estimates have ranged from the third century to the 14th, and speculations as to its place of composition have wandered through Jewish lands—from Christian Europe, to the Islamic East and, finally, to Byzantine Palestine. Scholars cannot even begin to guess the identity of its author or authors.

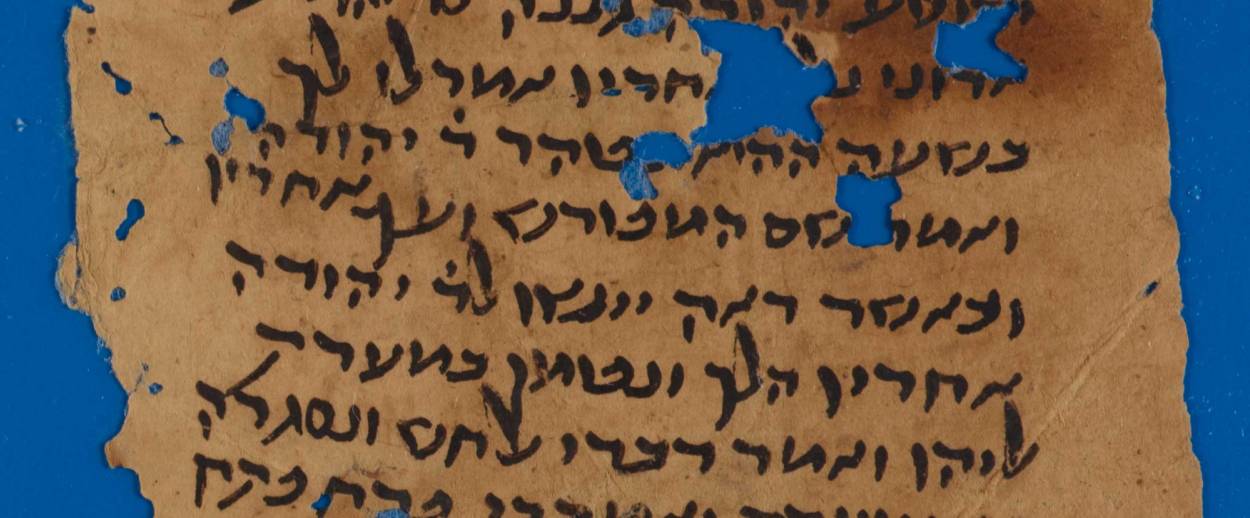

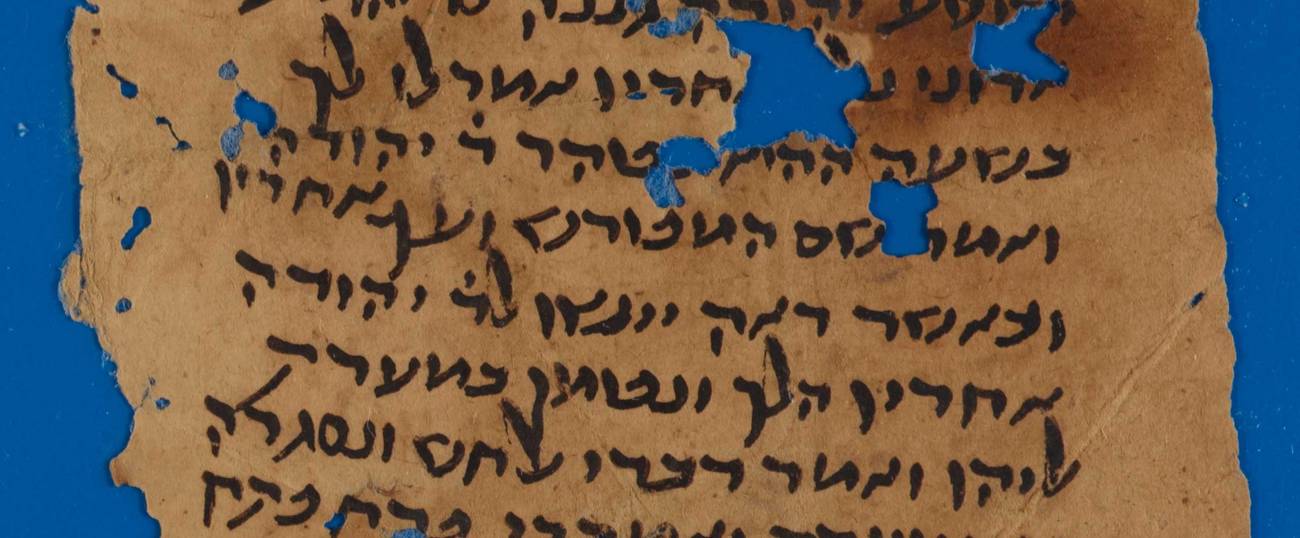

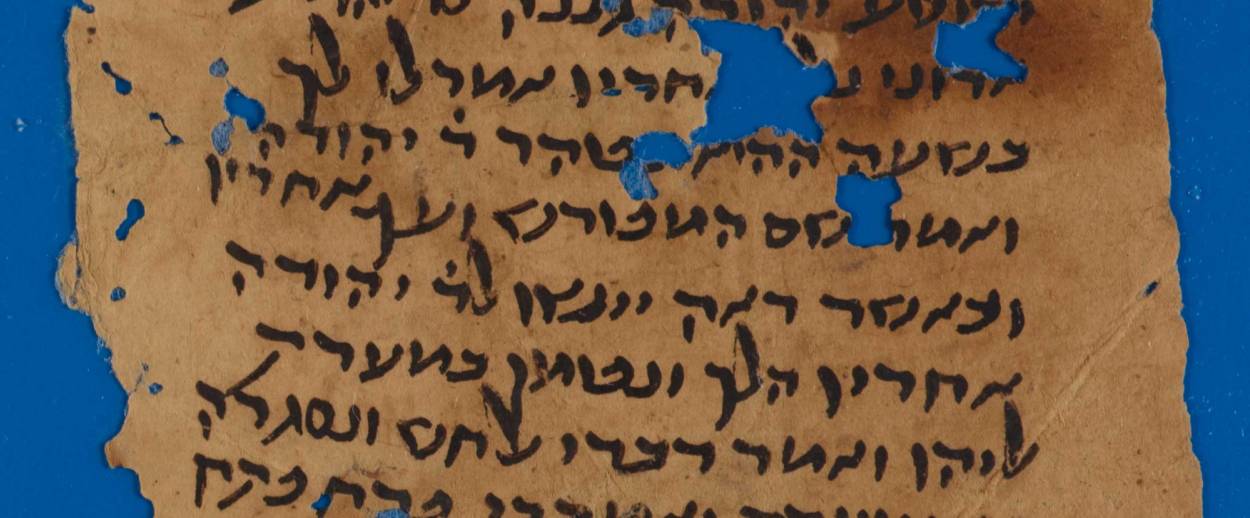

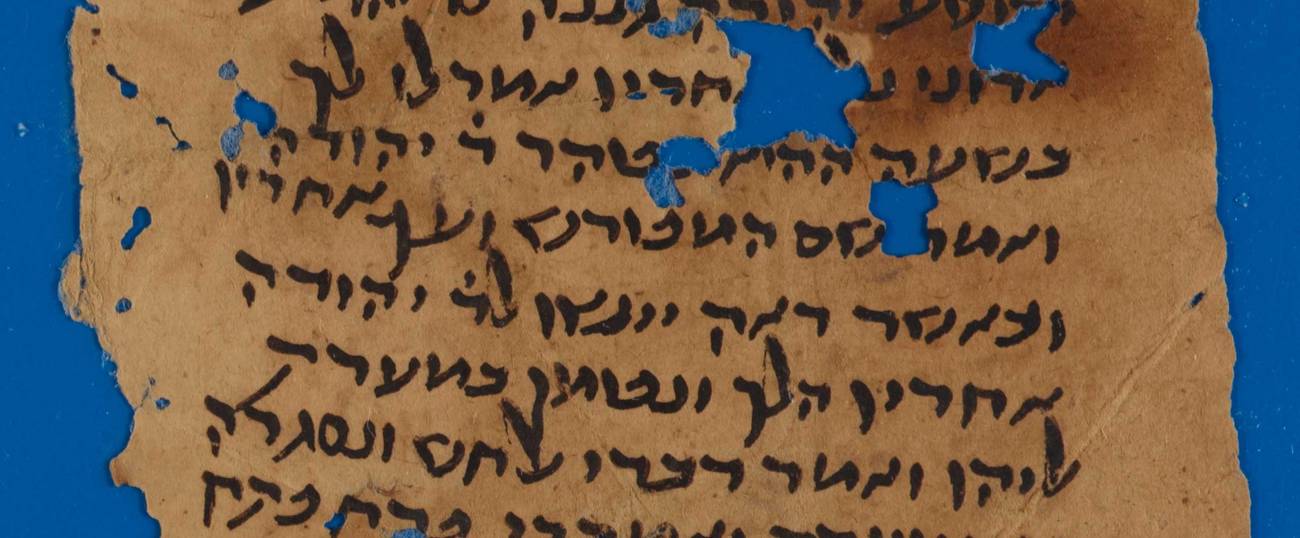

All that said, the immense scholarship surrounding the composition has established a number of reliable footholds. One of the most important finds has been the discovery of Toledot Yeshu citations in medieval Latin translation by Agobard, bishop of Lyons, and his disciple Amulo, around the year 800, in a copy apparently preserved in a monastic library. This find provides support for the claim that Toledot Yeshu existed and was already widespread in the eighth century. There have even been discoveries that point not to Christian Europe but to the East as its place of composition, and more specifically to the Jewish communities of medieval Iraq. This assessment relies upon the Babylonian Aramaic in which the earliest versions were composed, fragments of which were found in the Cairo Genizah, which makes sense: It is hard to believe that medieval European Jews would have had the nerve to put in writing, and then go as far as to circulate copies of, such a work.

It is generally accepted that Toledot Yeshu belongs to the rich genre of polemical literature that took part in the ancient contest between Judaism and Christianity. There is more than enough basis for this in the text, because Toledot Yeshu, like the religious disputations that proliferated from the beginning of the Middle Ages, contends with Christian dogma and then rejects it by making a mockery of it, and a coarse one at that. Be that as it may, what sets Toledot Yeshu apart, importantly, is in the execution—it does not recruit rhetoric or theological argumentation for its polemical ends, as does the rest of the Jewish polemical literature, but deploys narrative. Toledut Yeshu offers no counterarguments; it tells a different tale, it constructs an alternative narrative. It follows the main character from cradle (and even prior to birth) to grave in one long retelling, complete and seamless. It does not engage in debate, making this or that argument—it tells a story. From this perspective, Toledot Yeshu should be seen first and foremost as a literary creation.

Even as such it is innovative, intrepid even. We know of no work in all of Hebrew literature prior to Toledut Yeshu dedicated entirely to the literary biography of a single protagonist. Seen in this light, it paved the way for the biographical narratives that would be written later about cultural heroes like Moses, R. Judah the Pious, R. Isaac Luria, the Baal Shem Tov, and others. Another very interesting aspect of the work, from a literary perspective, is the multiplicity of versions. The dozens of manuscripts and early printing in which Toledot Yeshu has reached us present us with radically different, and at times even contradictory, renderings of the story. The anonymity of the work, alongside the multiplicity of versions, signal to us that we should view it as a folk-book, a Volksbuch (as termed in literary theory): Every Jewish community or storyteller took some artistic license, as storytellers have been doing since time immemorial, to rework, make alterations, embellish, or pare down, because each saw it as a kind of cultural property shared by the entire Jewish community. This finding is tremendously important, for it enables us to see how every community—each in its own time and place, each with its particular social situation and worldview—related to the Christian world and its beliefs, and how a Jewish minority living in the midst of a dominant Christian or Muslim majority attempted to cope with this reality.

Indeed, the book has the obviously polemical aim of mocking Christian dogma and scornfully spurning it. But, as with any complex work of art, it transcends its avowed intentions and succeeds in engaging with the life story of real people who are no longer treated as mere symbols and myths. The work thus expands its narrative boundaries beyond the narrow focus of its polemical surface goals.

The basic Christian myth marked as the first target for derision, toward which the barbs of Jewish criticism were aimed, was obviously the Virgin Birth. Whereas polemical literature contended with it by using arguments that are “logical” (it is impossible), theological (God has no physical dimensions), and exegetical (Isaiah 7:14 intended something other than a virgin birth), Toledot Yeshu takes a completely different tack—it tells a story. And so we have Mary, a virgin from Nazareth, being impregnated by a Roman officer or adulterous neighbor by the name of Pandera or Pantera, who lusted after her not only while she was engaged to her fiancé, but even worse, while she was menstruating.

The accusation that Mary attempted to cover up her extramarital pregnancy by fabricating a story about a virgin birth is not a virgin contribution of Toledot Yeshu. Such reports were widespread in the earliest pagan polemics against nascent Christianity, and allusions to it can be found in Talmudic literature. Unlike mere rumor, however, Toledot Yeshu creates a complete narrative episode. It has lust for an innocent maiden, seduction, deception, a cuckolded husband, and a pregnancy concealed by the adulteress through great cunning, a tale surprisingly reminiscent of the novellas in Boccaccio’s Decameron yet predating them by centuries. Thus Jesus was reborn as a “bastard, son of a menstruant,” an epithet that has stuck ever since within the Jewish world.

When Jesus was sent as a child to study in the study hall with other children, he was discovered to be a prodigy, sharper and more diligent than everyone else. As one of the earliest versions tells it, though, these qualities were of no avail to him:

It came to pass after these things that the wicked one [Jesus] played with the lads outside, as lads playing together are wont to do. The wicked one angered the lads with his playing. The lads said unto him: “Bastard, son of a menstruant! You think you are the son of Johanan? You are not his son, but the son of Joseph Pandera, who bedded your mother in her menses and sired you, evil begotten by evil.” Whereupon hearing these words the wicked one ran to his house, to his mother, fuming, and let out a great and embittered cry, uttering: “Mother! Mother! Tell me the truth straightaway. When I was little, the children used to say that I am a bastard, son of a menstruant, but I thought it a tease. But now the lads, all as one, hoot at me, day in and day out: ‘Bastard, son of a menstruant!’ They tell me that I am the son of Joseph Pandera, who came unto you in your menses.”

Jesus the boy, the prodigy with a bright future as a Torah scholar, tries to fit in with his peers, only to face rejection when the boys repeat obscene gossip undoubtedly heard from their parents. This most humane depiction of a boy bullied by his cruel classmates, who runs to his mother and cries bitterly about the dark secret poisoning his life, is quite far from the stereotypical or polemical. For this life of degradation and rejection has nothing to do with him or his character traits, it is imposed upon the young child by his parents and bitter fate.

The picture that emerges from the narrative completely undercuts the epithet that appears at the beginning of the piece and in its continuation (and throughout the entire length of Toledot Yeshu)—“the wicked one.” The story itself tells of a wretched and ill-fated boy, not an evildoer. The same cannot be said for his classmates and playmates, and certainly not for the parents spreading the vile rumors, because it is precisely those representatives of “normative” Jewish society within the narrative who are wicked and make this talented and spurned boy’s life miserable.

Another early version of Toledot Yeshu paints an even graver picture:

And it came to pass in those days, that the court of that place would adjudicate the cases of the people, but they would pervert their judgments for bribes and out of favoritism. This Jesus the Nazarene would sit with them and reprove them, time and again, about justice. They would threaten him, and he would remonstrate with them about it in a quarrel […] He became a thorn in their side, and so they sought a pretext to distance him from his seat among them […] [When Jesus left on a errand to a village,] the court summoned his mother Mary, after her husband Joseph had died, and made her swear by the Name that “you shall tell us whence this young man Jesus came to you, whose son is he? For he has been impertinent with us.” […] Upon Jesus’ return from the village, he came to sit in his usual seat. The court rose and hustled him, saying to him thusly: “A bastard shall not enter into the Congregation of the Lord.” He said to them: “Even were it as you say, I am wiser and more fearful of God than you, and I will not withhold His reproof from you.” […] They answered him: “From now on we shall not heed your words; you shall not even sit amongst us, for you are a bastard.” He pleaded with them but they would not be appeased. At last he grew weary and distant on account of their determination, and “Jeroboam went astray.”

In the first piece, Jewish society rejected Jesus from birth as a result of his misfortune. In this second piece, it’s even worse: Jesus is an upright man fighting for justice and truth in a corrupt Jewish society, and his noble activity leads to his rejection and excommunication. This account, too, mentions the vile gossip about his origins, which the judges wring from his mother through intimidation. Unlike the previous version in which the children used it to mock him, here the judges use it to expel him from their midst, so that they may continue in their depravity without hindrance. This description relies, in fact, upon the Gospels, which presented Jesus as fighting against the corrupt establishment in charge of the Temple, but this account much more powerfully depicts the moral chasm separating Jesus and the Jewish establishment.

This narrative episode, which closes with expression “Jeroboam went astray,” echoes the biblical story in which the pride of Solomon results in the breakaway of the northern kingdom from the United Monarchy. Used here, it establishes a causative link between the banishment of Jesus at the hands of the corrupt court and Christianity breaking away from within Judaism to eventually become its own religion. In the previous episode, too, which tells of the insults Jesus endured at the hands of his playmates, he expressly declares: “If I am a bastard, son of a menstruant, I shall act like a bastard, son of a menstruant.”

What caused the breakaway of Jesus from the Jewish people, the establishment of an alternative to the Jewish Torah, and the founding of the Christian religion, was clearly the extremely callous and degenerate behavior of Jewish society. The children, parents, and rabbinic establishment, who all harshly pushed away the atypical child and the judge who fought for truth and justice, all carry clear blame for the consequences of their actions. This critique leads to the following troubling question about the story: Had the Jewish community not acted toward Jesus the way it did, would he not have become a Torah prodigy, would he not have become chief justice of a just court, the pride and joy of the Jewish people? Perhaps Christianity would have never come into being at all, and the terrible suffering it visited upon Jewish society would never have materialized, if only Jewish society had been more humane and merciful?

If we return to the consideration of Toledot Yeshu from a literary perspective, we would see that this is precisely the narrative turning point in which the anonymous child protagonist becomes a charismatic religious figure, the private individual morphs into a national leader, and finally assumes the mantle of the messiah. Until now, the subject of Toledot Yeshu has been the personal fate of the boy Jesus; now it focuses on his public persona. To complete this metamorphosis, however, the protagonist needs to procure the means that will grant him the power to persuade the masses of his ability to influence their lives, which is the secret of charismatic leadership. This question preoccupied, in fact, both the first Christians and their Jewish and pagan adversaries. Where the New Testament saw the source of Jesus’ power in his divine essence, the adversaries defined his power as black magic deriving from the forces of evil. “Jesus as sorcerer” was a prevalent and accepted motif amongst pagans and Jews at the inception of Christianity.

Toledot Yeshu, on the other hand, chooses a different path of surprising originality. It relates that the Foundation Stone upon which the world was established, which is hidden under the foundations of the Temple, is inscribed with the Ineffable Name. This Name is the most closely guarded secret of Judaism, an extremely powerful means by which someone can work miracles and harness the forces of nature. The Rabbis worried that the Ineffable Name might be stolen and become a devastating force in the wrong hands. Therefore, they devised a way to erase the memory of anyone seeking to memorize this secret of divine holiness, and to spirit it away to some location outside the holy precincts.

Jesus, upon being banished from Jewish society, decided to avenge himself. He entered the holy precincts, inscribed the Ineffable Name on parchment, made an incision in his thigh, stuck the parchment into the cut, closed the wound, and left, with no one the wiser. This way, even though he forgot the name that he had tried to memorize, upon returning home he removed the parchment from his flesh and thereby deceived the Sages of Israel. Now, with the Ineffable Name in hand, he could use it to work the miracles that would be described in the New Testament, the ones that won him the admiration of the masses and inspired their belief that he was the messiah and Son of God.

In a religious polemic, there is no move easier to make than to accuse one’s opponent of sorcery, thereby putting him in league with all things evil and demonic. The question that cuts to the heart of Toledot Yeshu’s meaning, then, is why this work, in almost all versions, decided to ignore the longstanding tradition of Jesus as a sorcerer and instead gave him the Ineffable Name. The story appears to contain the following polemical argument at its base: The foundation of Christianity is rooted in an underhanded theft of one of the most hallowed possessions of Judaism. But the argument is more complicated still, for it does not deny the truth of Jesus’ actions and the divine source of his power. Toledot Yeshu does not argue that the stories of Jesus’ wonderworking in the New Testament are lies; on the contrary, they are absolutely true because they flow from his getting hold of the holiest power of all, the Ineffable Name. If Jesus, in this narrative, represents Christianity as a whole, then a most bold claim lies between these lines: Christianity is not legerdemain or lies because it springs from the Holiest of Jewish Holies. The foundation of the Christian faith may lie in an act of deception, but one cannot gainsay its power and credibility. Thus, as a folk narrative aimed at the many broad strata of Jewish society, and not as a polemic intended solely for the learned, Toledot Yeshu seeks to expose and present the Jewish basis of Christianity, and to argue that the sources of its power and massive success came from Judaism.

In the story about Jesus stealing the Ineffable Name, another extremely important critical dimension appears to be present. Jesus used the stolen Name, and the wonders he worked through it, to prove that he was the messiah that Jewish society had been expecting every day. Jesus fulfilled, according to Toledot Yeshu, the main “requirements” for identifying the messiah: He claimed Davidic descent, worked miracles (revived the dead, cured lepers, banished demons, flew in the air), and altered the natural order. It follows that anyone who manages to hoodwink the rabbinic establishment by hook or by crook, and who appears to work real miracles or the mere semblance thereof, can present himself as the messiah and bring terrible and trying catastrophes upon the Jewish people, as Jesus did. The “Jesus incident” in Toledot Yeshu served as a cautionary tale for the messianic tendencies rife in the period of the work’s composition, which viewed every charismatic man claiming Davidic origins and working wonders or performing magic as the messiah, who then led thousands around by the nose, riled them up, and let them loose against the local authorities, resulting in the utter destruction of entire Jewish communities.

Although Toledot Yeshu understands the full gravity of the dispute with Christianity, it does not seek to lay all the blame at the feet of the Other, to place it all squarely upon the shoulders of the most detested personality in the history of Judaism—Jesus of Nazareth. From the foregoing, one should not get the impression that Toledot Yeshu tries to display any hint of positive appraisal of Christianity. Au contraire; it was written to combat Christianity, as one of the tools created by Judaism to be used in its ongoing fight against Jews joining the other side. At the same time, this important and complex work makes use of the “Jesus incident” to highlight what the authors saw as dark phenomena that had taken root in Jewish society over time. Toledot Yeshu does not shy away from turning the critical spotlight inward, within the Jewish camp. It blames the rise of Christianity upon Jewish society’s mistreatment of the lowly and outcast, its moral depravity, and its obsession with messiahs and messianism.

The uniqueness of Toledot Yeshu, as with any complex literary creation, lies in its ability to support varied readings of the reality it depicts. One can see incisive and occasionally crude polemic with Christianity, but also sharp and cutting criticism directed inward at the weaknesses and sins of Jewish society.

***

Translated from the Hebrew by Daniel Tabak. You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Eli Yassif is professor emeritus of Jewish Folk-Culture in The School of Jewish Studies, Tel-Aviv University. His book, The Hebrew Folktale: History, Genre, Meaning (Indiana University Press, 1999), won the National Jewish Book Award.