The Kabbalah of Rothko

In the gap between transcendental and concrete experience, 48 years after the painter’s death

To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. —Theodor W. Adorno

In Houston, in a small middle-class neighborhood, on a quiet street lined with oak trees, sits the unassuming Rothko Chapel, surrounded by a big lawn, a wall of overgrown bamboo, and a reflecting pool that enshrines Barnett Newman’s imposing steel monument, Broken Obelisk. The combination of the chapel’s bland, windowless, tan-brick exterior with the somewhat heavy-handed Obelisk is an initial bummer. But the suite of Rothko paintings that line the room is nothing less than transformative, and once the initial emotional impact begins to wear off, one can reflect on the room’s architectural precision and painterly detail.

The 14 site-specific paintings in the Rothko Chapel read as a multipanel work of monomorphic chromatic art. Each panel is essentially tied to the next by a haze of filtered natural light. The artworks themselves are so integral to the space and to one another that, to an untrained eye, they could almost be mistaken for the chapel’s walls. After Rothko and Philip Johnson, the chapel’s original architect, had a disagreement and parted ways, two other architects from Johnson’s firm took over. The chapel’s design is so reductive, so stripped down to essentials, that one is not struck by the hand of any architect but rather given the opportunity to feel pure unadulterated Rothko.

The chapel’s near brutalism juxtaposes nicely with the paintings’ sensuous, vulnerable fields. It’s as if the room is a nocturne—a forest with moonlight filtering through its canopy. Even by day, the paintings provide the quiet solitude and mystery of night. The dark presence of the canvases seems to articulate light itself and allow one to commune with the chapel’s radiance. Dark as they may be, their geometric forms, alternating between translucence and opacity, create a milky luminescence and a compelling spectrum of tones and temperatures.

From its inception, the chapel offered a haven to Rothko himself, who was desperate for a context outside the toxic New York art world and for the nurturing he needed to venture onward in his work. Despite his enormous success by the mid-1960s, Rothko was finding it increasingly difficult to feel rewarded or challenged by exhibiting and selling knockout paintings. The chapel gave Rothko the opportunity to home in on, and realize, one of the last objectives of his late career, which was to create a kind of circuit of permanent, site-specific paintings that would have a greater visceral impact on viewers than any work he had previously done.

The octagonal chapel was designed with a Greek cross (+) in mind and was originally intended to be Roman Catholic, Rothko’s initial referent being the Byzantine Cathedral of St. Maria Assunta in Torcello, Venice. However, without a gold dome or mosaic of the Madonna and Child or bell tower, the chapel is hardly reminiscent of a northern Italian basilica. And yet, the chapel retains a definite Christian aura. Three of the paintings are triptychs, a form invented in the Middle Ages to provide pop-up altarpieces illustrating generic crucifixions. Perhaps the chapel’s most strikingly Christian gesture is found in two of its three triptychs, which are nearly identical. In both, Rothko—swayed by an offhand remark after the works were complete—chose to elevate the central panel about 6 inches, a gesture that, given the chapel’s overall starkness, stands out as a bold reference to the Christian cross.

What would have led Mark Rothko—a Jew, albeit a nonpracticing Jew—in such a Catholic direction—in Houston, of all places? The concept for the chapel was cooked up by the legendary Houston-based philanthropists Dominique and John de Menil, who were motivated by their interest in the ecumenical movement in Christianity to establish a one-size-fits-all sacred chamber for prayer and meditation. As John de Menil wrote not long after the chapel opened: “Without staff, without organized programs, just by keeping its doors open eight hours a day, [the chapel] has become a place of election for peace, for quiet contemplation and prayer.” Today, the chairman of the chapel’s board of directors is Mark Rothko’s highly charismatic and brilliant son Christopher Rothko, and the chapel is in constant use, hosting weddings, memorials, baptisms, philosophical exchanges, colloquia, and a broad range of spiritual and musical performances.

To what extent Rothko believed in the chapel’s mission is another question; one can only imagine the skepticism of a judgmental, depressive Jewish artist getting involved in the creation of a Christian church with a high-profile architect known for his arrogance and sympathy for German Fascist dictators. Nevertheless, the de Menils believed that a room of Rothko’s would possess a universal spiritual force, and they fearlessly led their pet abstract expressionist from the secular into the spiritual. Today, while many gravitate to the chapel and revel in its sacred vibrations without a moment’s hesitation, others stand poised with iPhones, yoga mats, and credit cards, scratching their heads. It’s simply too good to be true.

Indeed, part of the answer to the mystery is money. Yes, money does talk. And money can also make God talk. It should thus come as no surprise that money was (and still is) flowing from the de Menils, who up until 1997, when Dominique died (John died in 1973), were among the wealthiest art patrons in the game. Dominique was heiress to the Schlumberger oil-industry fortune, and in 1932 after having married the banker John de Menil, the couple relocated to Houston from France. John quickly rose in the ranks of his wife’s family business to president of the Middle East, Far East, and Latin America divisions of Schlumberger. Even with Schlumberger’s supposedly high “Green” ratings, and the de Menil family’s altruism and extreme generosity, the words “Texas,” “oil,” and “Middle East” are likely to raise eyebrows, even at the peaceful little Rothko Chapel.

If Rothko is playing the part of the martyr here, then the de Menils are surely the saints. Their generosity is staggering, and there are far too many fascinating stories connected to the family dynasty for me to even scratch the surface—from the creation of the Dia Art Foundation in 1974 by Dominique’s daughter Philippa de Menil (and her art-dealer husband, Heiner Friedrich, and their close friend Helen Winkler); to Dominique’s other daughter, the fashion and jewelry designer Christophe de Menil, and more recently Christophe’s grandson, the hipster-artist Dash Snow (who sadly died of an overdose in 2009 after skyrocketing to fame with little more than a stash of gnarly salacious Polaroids that are nonetheless exquisite). Fortunately, even the outsize money and personalities of one of the world’s largest oil families do not contaminate the purity of the Rothko Chapel, which comes across as a place that, from day one, was simply meant to be. But where did it come from?

In his recent book Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out, Christopher Rothko broaches the topic of the influence of Judaism on his father’s art. But one can sense the author’s reluctance to debate the subject, and rightfully so, for it can be almost painful to burden Rothko posthumously with an identity and faith he so deliberately and successfully shed in his lifetime. While Christopher Rothko admits that abstract expressionism may have a bit of the Talmud at its core—asking “Does Rothko’s fully abstract color-field style derive from biblical prohibition on making a graven image of the human figure?”—his answer is ultimately dismissive, which is harsh for the population of Jews in the world who want to claim Rothko as their very own mystical modernist prophet. Christopher has great conviction and sensitivity to the fact that his father was not a practicing Jew and that there is no clear sign in his writings or art that he ever thought of himself as a maker of progressive Judaica.

Under normal circumstances, I wouldn’t disagree. But the chapel is a strange sort of anomaly and a departure from the rubric of abstract expressionism. And as gentrified as Rothko was by the 1950s and ’60s, underneath he was about as Jewish as they come. Born in Dvinsk, Russia, to an Orthodox Jewish family, Markus Yakovlevich Rotkovich formally studied the Talmud in a Jewish school, and in 1913, when the family immigrated and settled in Portland, Oregon, he became an active member of a Jewish community center, where he developed a rebellious, leftist Jewish attitude, which stuck when he went to Yale University and then to New York. Perhaps we are ready to investigate Rothko’s complexity and ethnicity without attaching labels? Perhaps there is also an increasing anxiety about an increasingly homogenous America that does too little to expose its real culture and roots? The venerable art historian Dore Ashton once compared Rothko’s use of light to the radiance of the Zohar, the principal text of Kabbalah. And I happen to think she was dead-on.

It was most likely Carl Jung who ushered in pop Kabbalah through his appropriation of Jewish mysticism in his famous book Man and His Symbols. But if this is true, then it is the German-born philosopher, historian, and Zionist Gershom Scholem who paved the way for Jung through his pioneering modern academic study of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism. According to Scholem, Kabbalah began in medieval times in Spain, when ideas about Will, Wisdom, Understanding, Kindness, Judgment, Beauty, Glory, Splendor, Foundation, and Kingship were written into the Zohar, an explorative commentary on the Torah’s Five Books of Moses. It is in the Zohar where the notion is articulated of humanity’s spark of divine light and primordial Adam possessing a unity of opposites.

Scholem explores how Kabbalah’s mysticism, metaphysics, and cosmology arose in reaction to a more rational conception of God (Socratic and Platonic in influence) as a distant and unapproachable deity. Soon in regions of Provence, Castile, and Gerona, a number of radical rabbinical leaders began to fuel a polemic that continued up until the Spanish “Edict of Expulsion” in 1492, when Sephardic Jews were driven out of Spain by the Catholic monarchs. (The edict was not formally revoked until—prepare yourself—1968.) About 400 years later, in 1933, a forum in Switzerland called the Eranos Conference convened for the first time, seeking to bring scholars of different religions together, Scholem being one of them. There he was given the opportunity to present his Hebraic research, which led to numerous articles in German and English journals, causing Kabbalah studies to become widely known for the first time among scholars of religion and psychology.

While Scholem and Jung did know each other personally, their influence on one another was complex. Jung suppressed his Jewish influences during the rise of Nazism, and in fact, he made many anti-Semitic remarks throughout the 1930s that he later retracted or contradicted. In 1928, perhaps as a result of his growing competition with Freud, Jung wrote, “It is quite an unpardonable mistake to accept the conclusions of a Jewish psychology as generally valid.” But in 1934—possibly due to his contact with Scholem at the Eranos Conferences—Jung expressed his gratitude for a people who were essentially down with his crackpot ideas: “I came across this impressive doctrine,” he writes, “which gives meaning to man’s status exalted by the incarnation. I am glad that I can quote at least one voice in favor of my rather involuntary manifesto.” In another confession, Jung writes to a friend that he had taken a “deep plunge into the history of the Jewish mind” to transgress “beyond Jewish Orthodoxy into the subterranean workings of Hasidism … and then into the intricacies of the Kabbalah.”

In his book, Christopher Rothko talks about Rothko’s interest in the writings of Carl Jung as well as Friedrich Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy, but he points out that it was Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious that had the greatest impact on his father’s thinking. “Whether or not Rothko subscribed to Jungian theory,” says Christopher Rothko, “it is clear that Jung’s ideas concerning the power and origin of myth were thick in the air that my father was breathing at the time.”

And what was this Jungian fog, exactly? Jung’s theories were, among other things, emissions of Kabbalah, Gnosticism, and Alchemy all fed with great erudition into a Christianized, modernized form of mysticism. The core idea: God is reduced to an inner divine spark in the primordial human, and religious experience is found through a turning inward into the Self. Indeed, Jung, in his own form of Alchemy, extracted gold, nugget by nugget, from the Kabbalah, in concepts such as microcosm mirrors macrocosm; God is unknowable and infinite; cosmic events can be conjured and related to the dynamics of our soul.

Rothko’s chapel can be seen as the perfect Carl Jung and/or Gershom Scholem case study house, for it seems to embody a yearning to elucidate a gap between transcendental and concrete experience. Archetypes—or paintings in Rothko’s case—are not merely expressive religious symbols, but a mechanism, a medium, for authentic transcendental symbiosis. But Rothko was not altogether cool with Jung’s morphing archetypes. In his 1947 essay “The Romantics Were Prompted,” Rothko says that the “archaic artist … found it necessary to create a group of intermediaries, monsters, hybrids, gods and demigods” in much the same way that modern man found intermediaries in Fascism and the Communist Party. “Without monsters and gods,” says Rothko, “art cannot enact a drama.” Rothko’s caution can be compared to Walter Benjamin’s critique, or “war,” with Jung in the following 1937 letter to his close friend Scholem, claiming to be “waging an onslaught” on Jung’s doctrines and archaic images and theory of the collective unconscious after discovering Jung’s “auxiliary services to National Socialism.”

Writer, curator, and architect Alexander Gorlin in his recent book Kabbalah in Art and Architecture (Pointed Leaf Press), which was accompanied by an exhibition at Sandra Gering called “Light and the Space of Void,” bravely goes down the Kabbalah rabbit hole. He pinpoints Kabbalist allusions in Rothko and Barnett Newman, as well as in the architecture of Louis I. Kahn, not to mention gentile architects like Le Corbusier. In a 2013 interview in Metropolis, Gorlin piques the imagination by comparing the concept of the tsim-tsum (the void) in the Kabbalah to Newman’s “zip” paintings and to the central water channel in Kahn’s Salk Institute building.

Gorlin’s research also dredged up a very obscure Rothko piece from 1928. It is a hand-rendered map of ancient Jerusalem that he drew for a book authored by a man named Lewis Browne titled The Graphic Bible. It was a project that occurred very early in Rothko’s career and that ended in an ugly lawsuit. According to Rothko’s biographer James E.B. Breslin:

The hearing for the suit produced seven hundred pages of testimony, three hundred of them from Rothko himself—the most elaborate record we have of Rothko as a young man. More important, the legal confrontation between Rothko and Browne posed many of the deeper issues of Rothko’s identity: the questions of who he was, who he was in relation to authority, who he was as a painter, who he was as a Russian Jew in America.

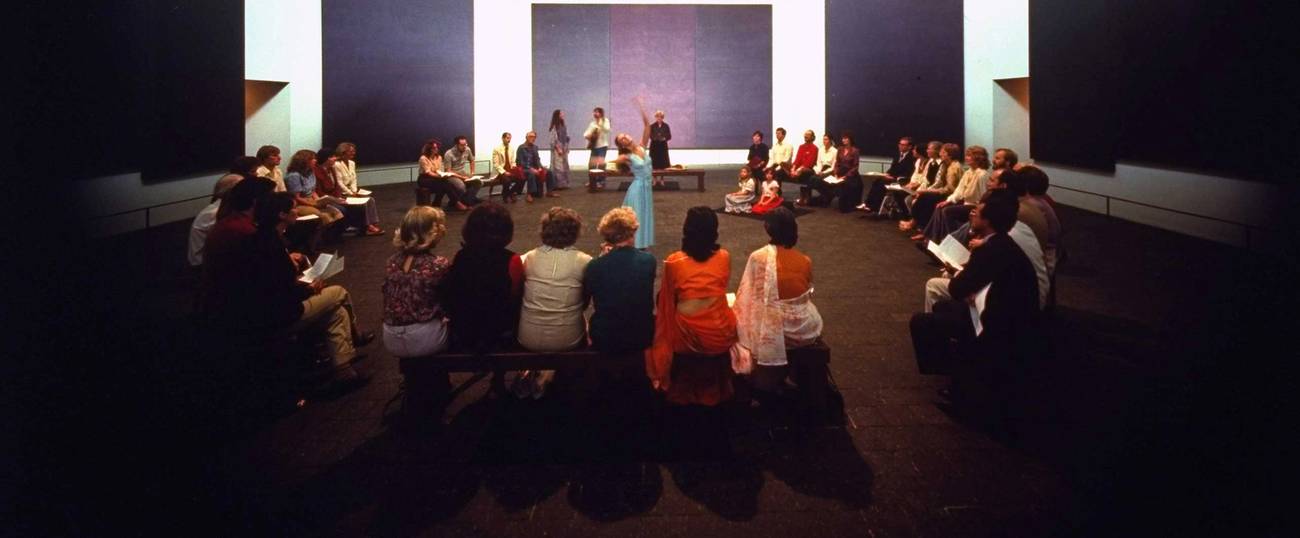

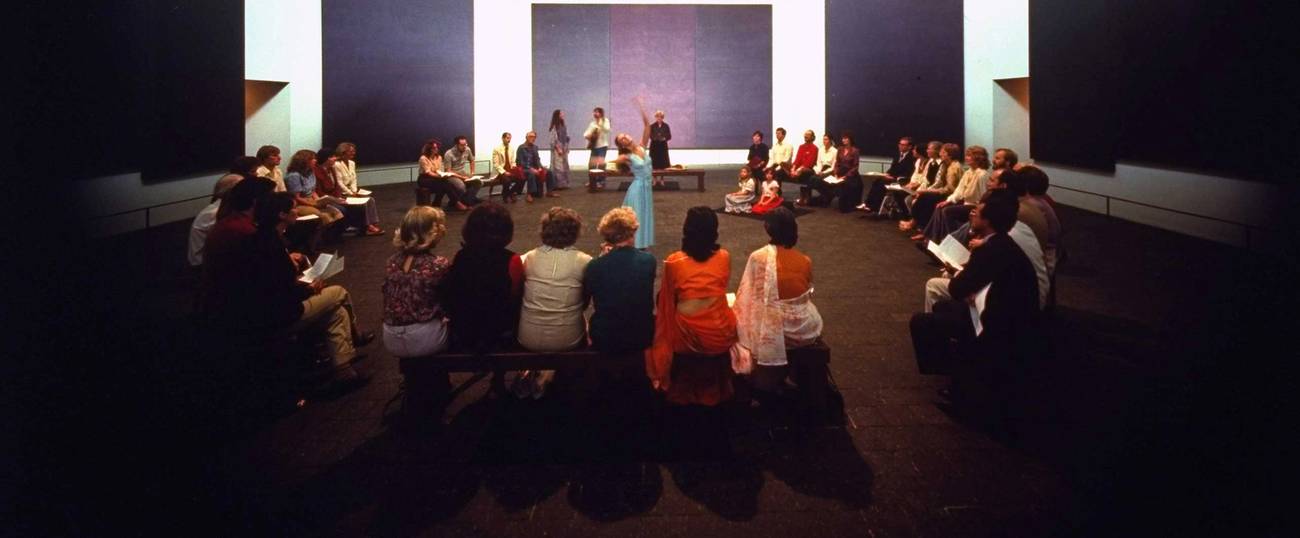

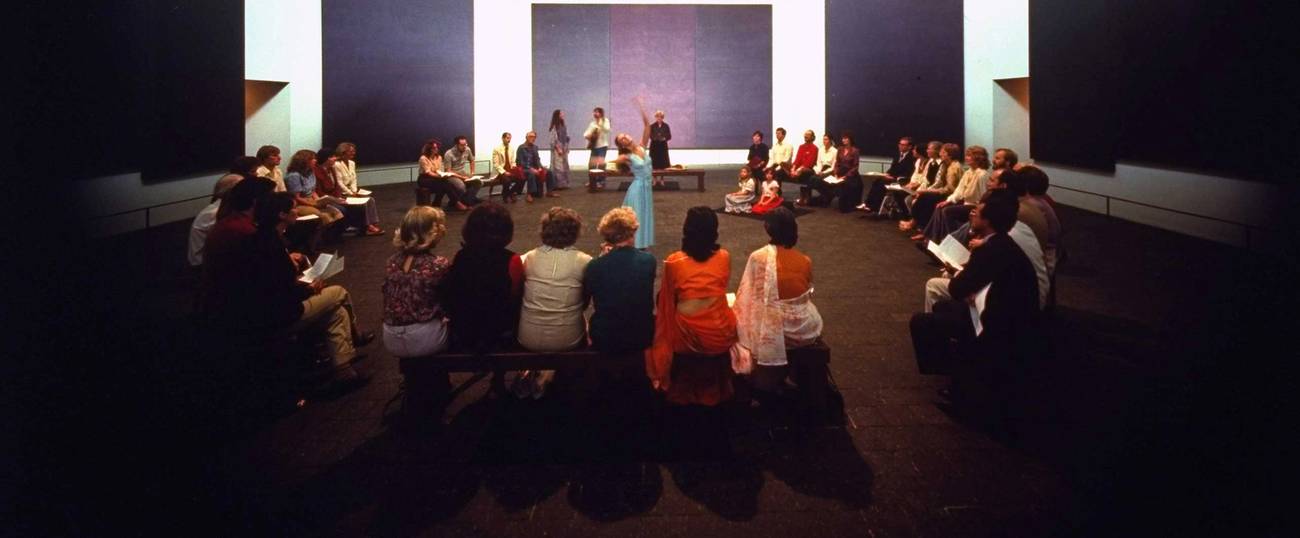

Another recent Rothko biographer, Annie Cohen-Solal, also examines Rothko’s relationship to Judaism in her book Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel (published as part of Yale’s Jewish Lives series). She argues that throughout his life, Rothko remained connected to his father’s Orthodox Jewish ways and his own Talmudic education. In one section of the book, Cohen-Solal describes a studio party Rothko threw in 1969 as a “primal reception,” where, according to Robert Motherwell, he hung his paintings in a circle and stood at its center for the entire party, “as if it carried some totemic power.”

I suspect (although it may be an unfair projection) that Rothko was the classic depressive, self-hating Jew who was nonetheless open and honest about his Jewish soul-searching when he was among his closest Jewish comrades. An example of this honesty can be found in the amazing 1983 oral-history interview with the major American poet Stanley Kunitz, a recording that exists in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian.

Kunitz, who was Rothko’s very close friend right up to the end, speaks of Rothko’s undeniably Jewish disposition, calling him “the last rabbi of Western art”: “When I said that to him once, he enjoyed it,” says Kunitz.

It made him feel very good. I meant that there was in him a rather magisterial authority, a sense of transcendence as well, a feeling in him that he belonged to the line of the prophets rather than to the line of the great craftsmen. It partly had to do with his appearance and his mannerism. You could imagine him being a grand rabbi.

And Kunitz then adds:

He certainly had very little Orthodox religion, but I think he felt strongly that he belonged to a great Judaic tradition, and that this was central to his art and to his life. It had nothing to do with the practice of religion but it had to do with the sense of being. But it was something that he could not articulate in language.

In his probing philosophical writings, Rothko seems very good, in fact, at articulating what I would call the Jewish piece of the metaphysical puzzle. In his essay “The Integrity of the Plastic Process” (published in 2004 in The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art, edited by Christopher Rothko), Rothko shows the extensiveness of his knowledge of the history of religion and philosophy. “Christian art,” he says, “can no more be called new than Christian thought itself, for that simply is the consummation of the meeting of East and West in Asia Minor, where Greek Platonism is combined with the mysticism of the East and the puritanical legalism of the Oriental Jew.” And in another essay, “Subject and Subject Matter,” Rothko states:

Let us remember that both the Greeks and the Christians demanded “works as proof,” and, being essentially naturalists, they were not admonished for the demand as were the Jews. Their senses found those works in the phenomena around them. In a sense both Jesus and Zeus, were in the position of scientists who were called upon at will to demonstrate this power to order nature.

In Rothko’s writing (as well as his art), it is pretty apparent that his Jewishness was not something he ever wanted to analyze, or deconstruct, or question, or put on display, but a given, a counterpoint, to which he could repeatedly draw comparisons.

As I entered the chapel, I felt myself crossing a very subtle threshold into a startling room (60 feet across and large enough to hold about 300 people) lit from one source, a baffled cupola in the direct center of the ceiling. I was also taken by the floor’s durable asphalt tiles that created a rough industrial all-purpose feel. It was apparent that Rothko based the interior of the chapel on the studio he was using at the time to create the paintings, a cavernous space on East 69th Street in New York where he erected mock chapel walls exactly to scale, as though he were already standing in the “chapel.” The studio, which had originally stored and maintained horse carriages, had a similar cupola and floor.

There was also something distinct about the chapel’s acoustics. Sound was very important to Rothko, and he referenced it throughout his career in a variety of ways. Once, he rejected the idea that his paintings were a language, calling them instead a form of speech. Much has been written about the silence that seems to ricochet off the paintings (negative speech, if you will). Rothko once said, “Silence is so accurate.” In a famously brief talk he once gave at Yale University, he described his work as a search for “pockets of silence.”

As John Cage pointed out in his wickedly smart 1952 musical composition 4’33” (where the performer sits at the piano, lifts up the keyboard cover, and proceeds to play nothing for over four-and-a-half minutes), silence is an opportunity to hear new things. Maybe this explains why, upon entering the chapel, I was immediately seduced by a very curious low hum (which the guard informed me was the building’s air-filtration system). For a brief second, in any case, I was reminded of the composer Morton Feldman, who was a close friend of Rothko’s, and who, in 1971, wrote a piece specifically for the chapel that also explored the chapel’s Jewish implications. In Alex Ross’s 2006 article on Feldman in The New Yorker, he speaks of Feldman’s lamenting, fleeting, dissonant, echoing, and lonely music, “that seemed to protest all of European civilization,” says Ross, as if all of Europe “in one way or another, had been complicit in Hitler’s crimes.” On one occasion, Feldman was in attendance at a German music festival when another American composer asked him why he didn’t move to Germany, and Feldman stopped in the middle of the street, pointed down at the cobblestones, and said, “Can’t you hear them? They’re screaming! Still screaming out from under the pavements!”

Rothko had strong political views about Fascism, Nazism, and the Vietnam War. But his rage carried over into many things, like bureaucratic museum institutions, the greed of the commercial galleries and collectors, and the critics who he generally felt were always getting him wrong when, for example, they would incorrectly label him a “colorist.”

Kunitz tells how Rothko’s depression, anxiety, and paranoia were beginning to get the best of him, especially after 1958, around the time he backed out of the Seagram Murals, a commission he had been given to paint a series of works for the lavish Four Seasons restaurant, which was still under construction at the time. After completing 40 breathtaking paintings in dark reds and browns, Rothko in an unprecedented fit of rage reneged on the deal, returned the advance, and stored the paintings until 1968, when they were given a permanent room at the Tate Gallery in London.

In 1968 Rothko’s health rapidly deteriorated, and he was diagnosed with a mild aortic aneurysm. He continued to drink and smoke heavily and became increasingly isolated and strung out. On Feb. 25, 1970, at the age of 66, Rothko took his own life (the crated works for the Seagram commission apparently arrived in England on the day of Rothko’s death). Just about a year later, the murals were delivered to the chapel. They were lowered by crane down through the cupola and quickly installed in time for an opening. At the dedication, Dominique de Menil praised the work for bringing us to the “threshold of the divine.” Rothko never saw the chapel completed—an abstraction that somehow seems fitting.

Back at the chapel, the light had changed. The sun had passed behind a cloud. The paintings were now emitting a bit less color—now they all seemed to be the same cool shade of gray. It was lunchtime, and the chapel was beginning to fill up with visitors, who, I assume, were mostly locals. I noticed one woman meditating in lotus position on one of the plump zafu pillows set down around the floor. There were at least 10 people standing before various panels in deep concentration. The feeling was of focus and balance, and everyone was tuning in, as if to another frequency. No one was visibly praying (or davening, ha ha). No one was sobbing. Rothko is famous for having once said that “people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationship, then you miss the point.”

But what about their color? They most certainly weren’t black. They have been called eggplant, aubergine, plum, chestnut brown, a velvety purplish black, and black mauves. They are indeed all of these colors in different lights, but they are also non-colors.

Maybe the canvases could be called “light catchers.” Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, the highly respected conservator who has been involved with the chapel since 1979, once determined that Rothko had mastered this magical game of light-catching through his sensitive brush handling, and consistency of paint, but mostly through the medium itself. (His secret ingredient: egg.) Indeed, the chremamorphism in the paintings is dependent not only on pigment, but on Rothko’s control over the slightest hint of reflectivity across the painting’s surface, and it is easy to miss how rigorous he was in developing, modulating, this surface, layer by layer. It has been noted that Rothko’s aim was not so much to create a panel of paint as to enclose the viewer in a spiritual twilight.

The romantic that he was, Rothko saw a painting as a place for a kind of intimate encounter with the viewer—a place for a vicarious bodily contact. He seems to have put his trust in the presence of the painted canvas to embody his spirit but to also absorb the spirit of the viewer. This idea, of course, plays into the Kabbalistic idea of death being a kind of divide between two worlds, but Rothko wanted to have this thrill, this exchange, while he was alive. Simply knowing that people were standing before his paintings seems to have filled him with a kind of warmth and sense of approval—giving him life.

There I was in the chapel, standing before the main triptych, which hung on a wall that was designed to be recessed about 5 feet. The painting, thus, was not so much hung on the wall, but in a niche. I stared up at the canvas’ breathtaking 15-foot expanse, which is when I noticed that I could not see its top edge. The painting was muted, blended, with a shadow that seemed to have been cleverly orchestrated, so that it appeared to be part of the painting.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.