The Kindest of Strangers

A new biography revives the generous life of Salka Viertel, L.A. ‘salonnière,’ memoirist, ‘Garbo specialist,’ and Jewish mother to Hollywood stars

If Salka Viertel did not know every literary, theatrical, or cinematic artist of note in the first half of the 20th century, it was not for want of trying. In later life, when she came to recount her friendship-filled heyday as a European stage actress, Hollywood screenwriter, and salonnière extraordinaire, she did not so much drop names as unleash a torrent of boldface personalities, certified geniuses, and marquee screen credits. If she is in Prague, Franz Kafka turns up at the dinner table. Munich? Rainer Maria Rilke is at the door with an invitation to tea. Santa Monica? Greta Garbo drops by for a walk on the beach.

The near-tandem publication of a new edition of Viertel’s luminous memoir, The Kindness of Strangers, and an essential companion piece by literary critic Donna Rifkind, The Sun and Her Stars: Salka Viertel and Hitler’s Exiles in the Golden Age of Hollywood, offers a welcome opportunity to look back on—and bask in the sheer decency of—a woman who was much more than the sum of her illustrious houseguests. An accomplished actress, a passionate anti-Nazi activist, and a gifted prose stylist in her fifth (sixth?) language, Viertel—herself an early harbinger of the mass migration—embodied the steely grit and quick-change skillfulness of a generation of Jewish artists who fled Europe steps ahead of the Gestapo. Throughout the 1930s, she worked tirelessly to get friends, acquaintances, and total strangers out of Hitler’s death trap, writing checks, soliciting donations, and lobbying the State Department for a more humane immigration policy. She welcomed many of them into her home, nurturing a vibrant exile community that earned the moniker “Berlin on the Pacific,” where German was as much a lingua franca as English or, for that matter, Yiddish.

Originally published in 1969, The Kindness of Strangers has gained steadily in reputation for its finely drawn character sketches, wry cultural-historical insights, and aphorisms on every page. (“Acting in fragments is like drinking from an eyedropper when you are parched,” she wrote of her first experience before the motion picture camera.) The work has also become a touchstone for academic scholarship in the burgeoning field of “exile studies,” especially the strand focused on the Jewish refugees who settled in Hollywood in the 1930s. Salka was at the center of the scene, her almost-beachfront, very lived-in home at 165 Mabery Road in Santa Monica serving as literary salon, crash pad, upscale soup kitchen, and safe space for the great, the future great, the has-been, and the never-was or would be.

Born in 1889 in the garrison town of Sambor, Galicia, then at the Polish edge of the wheezing Austro-Hungarian Empire and now in western Ukraine, Salka Viertel (née Salomea Sara Steuermann) grew up in a fin de siècle atmosphere of genteel privilege that seems as mistily remote as a medieval pageant. Her ludicrously talented family was Jewish which, as she remembers it, was no big deal either to them or their neighbors. Stern-on-the-outside father Josef Steuermann, a respected lawyer and the town mayor, brought electrification and modern sewage to the backwater. Mother Auguste was an aspiring opera singer forced into a marriage of economic convenience, but she passed the performance gene down to her children, especially precocious Salka, the eldest, who roamed the forests around the family estate imagining applause from rapturous audiences. Brother Edward, the family favorite, gained fame as a brilliant pianist and interpreter of the twelve-tone scale of Arnold Schoenberg; sister Rose was a top-billed stage actress; and the youngest brother, Dusko, was a natural athlete who became a champion soccer player.

In his graceful introduction to the new edition, Lawrence Weschler suggests that the reader may feel the urge to skim past the opening act and cut to the chase—that is, star-studded Hollywood—but Salka’s evocation of the lost world of her childhood and adolescence is utterly charming, like being transported into the set design of a Turgenev novel or Chekhov play. It seems unimaginable that in 1914 life would be swept away and by 1939 the grounds would be a killing field.

To her family’s horror, Salka was determined to enter the second most disreputable profession available to a girl of her learning and breeding: acting. Slave wages, exploitative contracts, and dawn-to-midnight hours—she loved every minute of it. “I always felt secure as soon as I had stageboards under my feet,” she recalls. The bosomy, leggy ingénue had to be nimble off the stageboards too, dodging pervy cast mates and predatory directors.

After the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand, “everything, which appeared built for eternity, began to falter.” While the empire imploded and armies crisscrossed the fields of the family estate, she and her sister Rose served as nurse’s aides. “What we desperately wanted to convey to those dazed, maimed men, was that we were personally concerned, and we tried to draw them out from the horrible anonymity into which they had been thrown,” she remembers, already striving to give more than medicinal support. Soon, the family is forced to flee their beloved home and become what she would later embrace—refugees.

***

In 1916, Salka met Berthold Viertel, an up-and-coming theater director, who, though married, resolved to wed her. Ditching his wife, he made good on the promise. Berthold was driven, self-absorbed, and, it turned out, a philanderer. She remained devoted to him, a pillar of emotional and financial support who subsidized his writing, stroked his ego, and even, when they finally divorced, befriended his new wife. Leaving the rearing of their three sons to Salka, Berthold spent most of her memoir anywhere but close to home—New York, London, Paris. What can one say? She loved the jerk.

After the Armistice, Berthold and Salka pursued her dream of revolutionizing theater in a Weimar Germany that conforms to Threepenny Opera expectations. Runaway inflation and hunger pangs coexist with a thriving art scene in theater, music, and film, and the couple drank deep of the best of it. At the movies, watching Mauritz Stiller’s The Saga of Gösta Berling (1924), she shares a moment of bedazzled spectatorship that is also a flash forward: “There was a loud gasp from the audience when the extraordinary face of the young Greta Garbo appeared on the screen.”

In 1928, Berthold got an offer from the Fox Film Corporation and the family pulled up stakes and moved to the promised land. In some ways, the timing was awful (the couple knew no English, the industry was converting to sound, and the stock market crash was around the corner) and in other ways fortuitous (they came to America as immigrants not refugees and, mirabile dictu, it was a buyer’s market in Los Angeles real estate). Ignoring the advice of locals who said Santa Monica was too far away from the action, she secured a mortgage on the soon-to-be-legendary homestead at 165 Mabery Road. “Contrary to expectations,” she understates, “moving to Santa Monica did not impair our social life.”

While Berthold struggled with English and the boorish moguls (to clear his head, he would retreat to the men’s room at Fox to read Kant), Salka managed the home and raised the boys. With her acting career stalled (“I was neither beautiful nor young enough for a film career,” she writes with characteristic self-effacement), she turned to screenwriting and parlayed her encyclopedic knowledge of European dramaturgy into the scripts that underwrite the ever-expanding needs of family and friends. Meanwhile, the three Viertel boys morphed into “dedicated Californians,” so much so that when she refused to sign a school permission slip for her 11-year-old son Peter to play football, he angrily yelled at her, “You—you—foreigner!”

Under Salka’s tender caregiving, the house at Mabery Road sprang organically into the destination of choice on Sunday afternoons, not just for refugees from Germany but for New York screenwriters, hustling actors, and other proto-bohemians who would rather not kiss the behinds of the big macher studio heads in Beverly Hills and San Simeon. The atmosphere of convivial bonne humeur and warm gemütlichkeit, of comfort food and cheap wine, makes the designation “salonnière” sound too grand for the down-home hostess. Everybody came to Salka’s.

The swirl of colorful personalities who arrived to schmooze and mooch is dizzying. (One of the flaws of the new edition, as with so many books in these penny-pinching twilight days of print publishing, is that there is no index.) Director F. W. Murnau, riding high after the success of Sunrise (1927), was a close friend (she rushed to his hospital bedside, but he had already succumbed to injuries sustained in a car crash); she took Soviet director Sergei M. Eisenstein to Aimee Semple McPherson’s Angelus Temple for an all-American evangelical hullabaloo (he loved it); and she bonded with the woman whose face had hypnotized her in Berlin, Greta Garbo (her reputation as the reigning “Garbo specialist” in town kept her in good graces with the powers at MGM). She knew Ernst Lubitsch from when he was a practical joker backstage in the German theater and not the genius with a name-brand touch. (Speaking of touches, Lubitsch was an easy one, bailing Salka out on more than one occasion when the mortgage was due. He balked only when she asked him to bankroll a restaurant. “You’ll be feeding the whole town for nothing,” he explains sensibly.) Commenting on a genius in a different field, she writes that the dinner she shared with Albert Einstein was “the most effortless and gayest evening I have ever spent in the presence of a great man.”

For all the intimate anecdotes and personal tidbits, Salka is discreet in a way no modern memoirist with an eye on the bestseller lists would ever be. The Kindness of Strangers is no tell-all; she kept her mouth shut about the homosexual crush Murnau had on the “Polynesian boy” who drove the death car. She is also never catty—well, almost never. Tallulah Bankhead set her teeth on edge “with her torrents of self-glorification.”

As “Hitler’s hideous demented voice carried across the Atlantic,” Salka was guilt-ridden for lolling about in the California sun while her kinsmen were squirming under the jackboot of Nazism. She joined the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, contributed to the European Film Fund for refugee relief, and hosted Popular Front fundraisers in the parlor at Mabery. In 1936, during a packed anti-Fascist rally at the Shrine Auditorium, she witnessed the birth of Hollywood-style radical chic as “ladies in mink clutching their bejeweled hands” mimicked the upright fist of the “red salute” of the Communist party.

For Salka, the war in Europe was personal; her family was targeted for annihilation. After Promethean exertions, she managed to get them all out of harm’s way, save for Dusko, captured by the Nazis in an Aktion in the Ukraine. All she could learn of his fate was a report that he was shot by the SS after leaping from a train bound for the death camps. She could only hope that he died in an act of resistance. Little wonder that, unlike so many of the exiles who gladly returned to Germany or Austria after the war, she felt a permanent alienation. “I never considered going back,” she writes, not bitterly, just stating a fact. “I did not believe that all Germans were Nazis; but that even those who had Jewish friends had tacitly accepted their disappearance, the unspeakable horrors and the mass exterminations made it impossible for me to return.”

Given her fierce anti-Fascism and open door to refugees of all stripes, it is no surprise that Salka ran afoul of the postwar anti-communist crusade in America. It is hard to tell how she was stamped persona non grata by the studios, but the work dried up with suspicious synchronicity. Though she was never called to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, her FBI file was thick enough with allegations to raise red flags with the State Department. In 1953, she was denied a passport for foreign travel. During a clearance interview with an officious State Department flunky, she was asked if it was true that she had said she preferred any form of government to the one in the United States. “Do I give the impression of being a moron?” she snapped back.

Forced to cool her heels in New York waiting on her stalled passport, Salka spent Christmas Eve alone in a small apartment until a knock sounded on the door: Greta Garbo, also alone (of course). She whipped up a quick meal and the two old friends shared shots of vodka.

The memoir ends soon after, in 1954, on New Year’s Day, with Salka journeying to Klosters, Switzerland, to meet her 2-year-old granddaughter Christine. The instant the little girl reaches up to touch Salka’s white hair, “a tidal wave of tenderness and love engulfed my incorrigible heart.” It is the last line of the book.

Ultimately, Salka decided to settle in Klosters to be near her granddaughter, and it is in that snowy Alpine destination for celebrity skiers that she lived out the remainder of her days, working on her memoir while living in cramped quarters above a butcher shop. When she died in 1978, almost no one seems to have noticed.

***

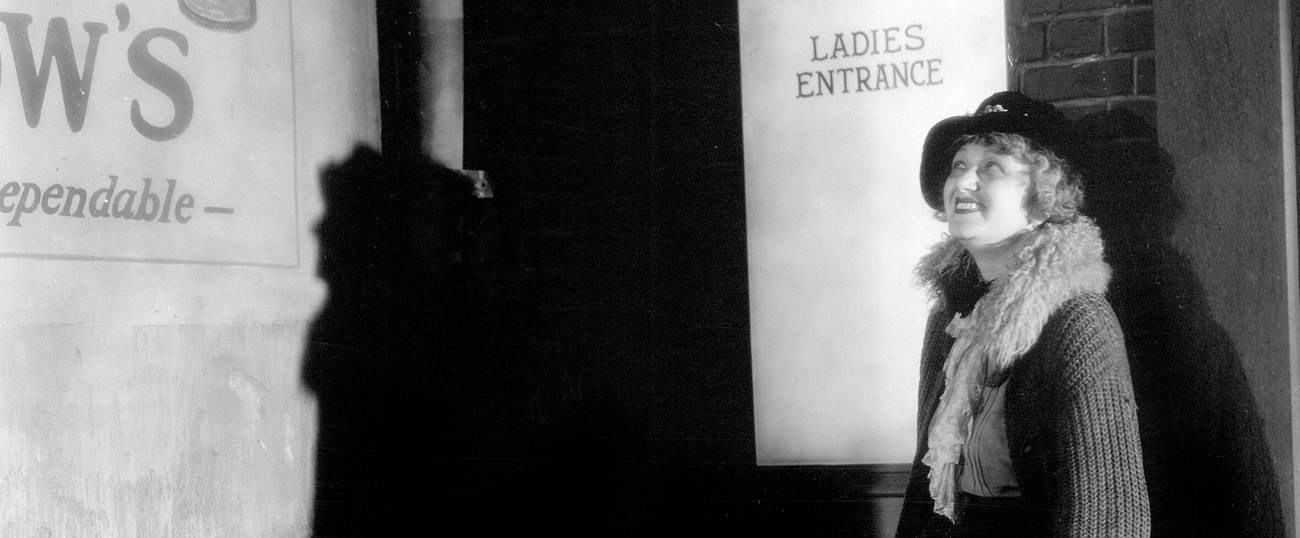

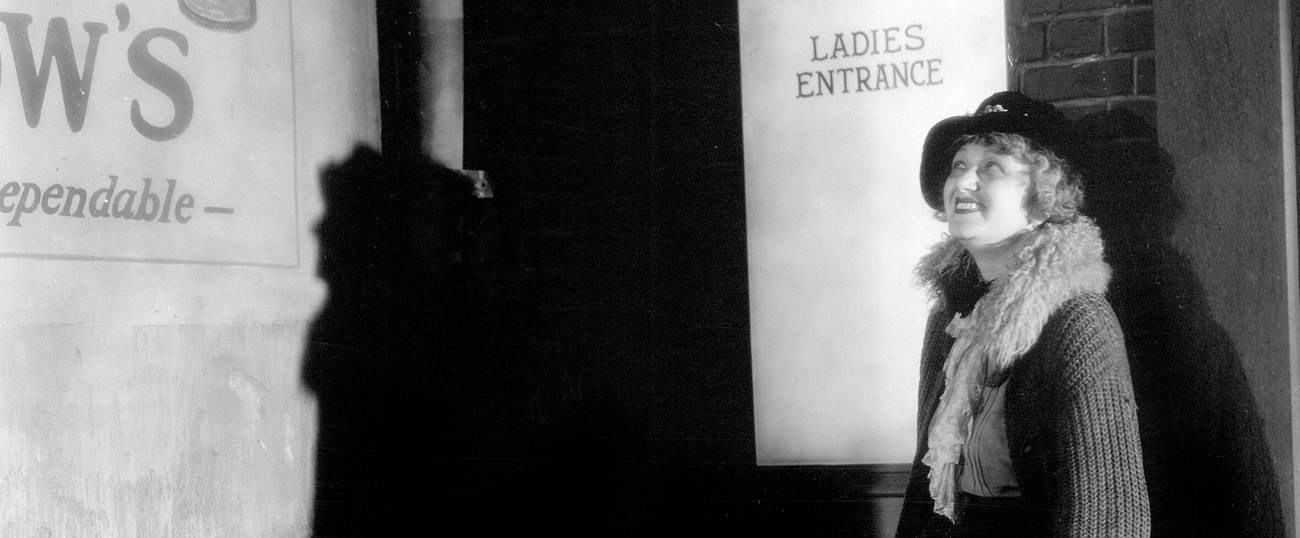

Donna Rifkind aims to remedy the oversight. In The Sun and Her Stars, she fills in the blanks that Salka left empty, provides context and background, and chronicles Salka’s post-Kindness life during her final and loneliest exile. Rifkind’s affectionate and meticulously researched study seeks to write back into history a woman whose legacy is more intangible than the screen credits and bylines of the artists she befriended, whose legacy is found in the many lives she sustained and saved. (Salka’s most noteworthy screen appearance was in the German language version of Anna Christie (1930), where she plays opposite Garbo.) To move outside the memoir, Rifkind draws heavily on the trove of letters and diary entries in the Berthold and Salka Viertel papers at the Deutsches Literaturarchiv in Marbach, Germany. “We’re so glad you are here for Salka,” says an archivist when the author arrives. “Almost everyone comes for Berthold.”

Readers who have fallen in love with the Salka Viertel of the memoir will be reassured to know that the woman Rifkind portrays is as good as the legend. To be sure, she reveals a few sides and specifics that the memoirist passed over in silence or veiled allusion. Like Berthold, Salka had her share of extramarital affairs, some “retaliatory and fleeting,” others more serious, including a decadelong relationship with Gottfried Reinhardt, son of Max, 20 years her junior. Here sometimes Berthold’s vaunted European sophistication did not prevent him from a jealous application of the double standard. “Torn and inconsistent, Odysseus resented bitterly that Penelope had not waited patiently for his return, though he himself had not renounced the Nausicaas,” was Salka’s droll comment.

Ending in 1954, the memoir spares the reader the singular tragedy of Salka’s later life. She and her daughter-in-law Jigee (mother of her beloved granddaughter Christine and ex-wife of son Peter, the frustrated footballer) had remained close since Peter and Jigee’s divorce, the two women having bonded during WWII when Peter was a Marine serving in the Pacific. In 1959, Jigee suffered horrible burns in a fire and, after five agonizing weeks, died in hospital.

Hoping to care for Christine, Salka settled permanently in Klosters, but the girl was shunted off to a boarding school and she saw her only intermittently in the ensuing years. Salka’s circle of friends shrank—most died, some forgot—but she still had a supportive network of comrades from the old days. The ever-loyal Garbo came to visit and ski every summer. Charles Chaplin welcomed her to his ostentatious manor house in Corsier, Switzerland. By then, it was Salka who was the tramp. For the train fare back home, Rifkind reports, she had to borrow 40 francs from Chaplin’s wife, Oona.

The welcome mat Salka put out for Jews, Communists, and homosexuals (and for people who were all three) was a gesture “quietly but transgressively courageous,” writes Rifkind. Peering into the “incorrigible heart” of her subject, she speculates that the roots of Salka’s penchant for hospitality reside in a Judaic tradition “known in Hebrew as hachnasat orchim, the taking of guests,” an inheritance from her mother, who always had a pot of soup ready for the starving soldiers and bedraggled refugees who shuffled by the family estate.

Perhaps. The woman of the house at 165 Mabery Road seems not to have given it much thought. Nor would it have ever occurred to Salka Viertel that the kindest stranger in her memoir was the author.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Thomas Doherty, a professor of American Studies at Brandeis University, is the author of Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 and Little Lindy Is Kidnapped: How the Media Covered the Crime of the Century.