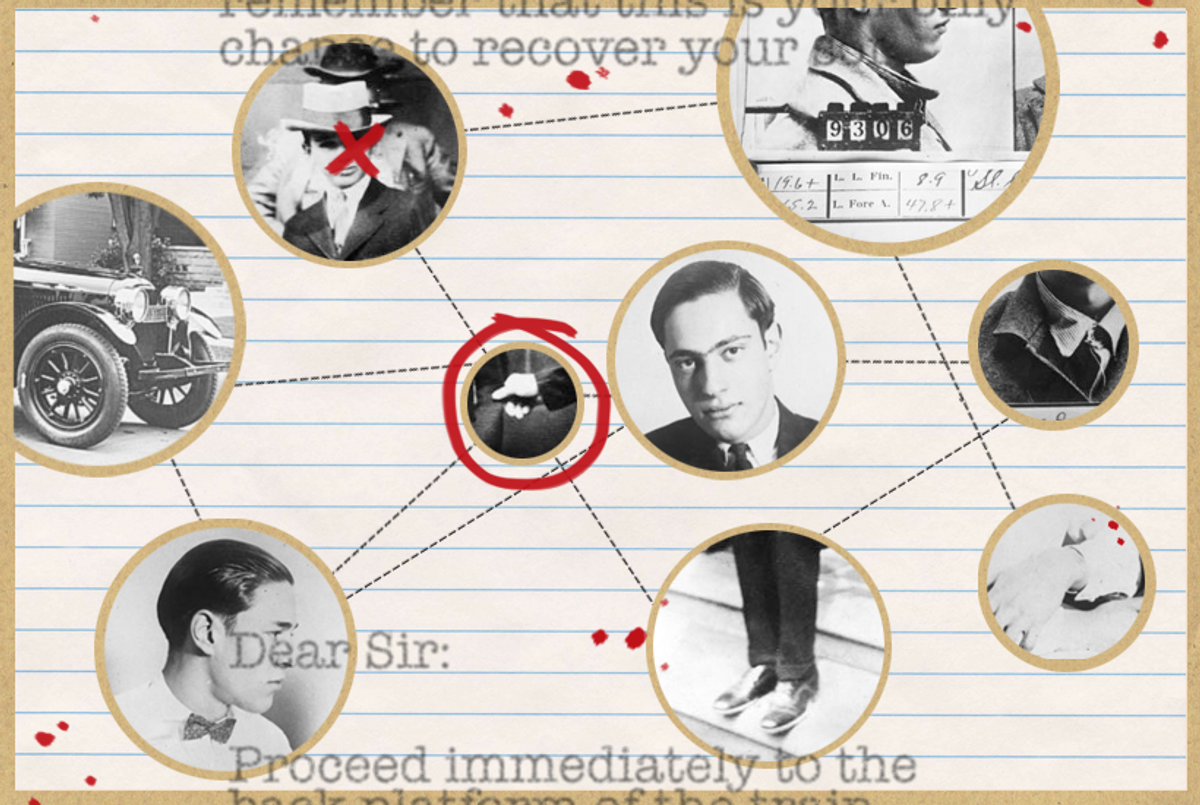

When you think of how many people have died violent deaths in the last 90 years, it’s strange that a single murder from 1924 should still be remembered at all, much less regarded as the crime of the century. But the killing of 14-year-old Bobby Franks by Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb was no ordinary murder. We are used to murderers who kill out of greed, rage, jealousy, fear, or hatred; we are even used to genocides committed for ideological or political reasons. What is hard to comprehend, even today, is a murder committed for no reason at all. Yet when Leopold and Loeb, two teenage friends from wealthy Jewish families in Chicago, convinced Franks to get into their car one afternoon after school and then beat him to death with a chisel, the sheer absence of motive was itself their motive. Their goal, they explained during the subsequent investigation and trial, was to commit a “perfect crime,” by which they meant one that was entirely gratuitous, conceived as an intellectual project and carried out with a kind of scientific detachment. “It is just as easy to justify such a death as it is to justify an entomologist killing a beetle on a pin,” Leopold explained.

It’s no wonder that so many writers and filmmakers have been drawn to the Leopold and Loeb case, since the crime itself was so literary in inspiration. The killers, both child prodigies who graduated from the University of Chicago while in their teens, had absorbed their moral detachment from famous books: Crime and Punishment, where Raskolnikov philosophically justifies his murder of an old woman; Lafcadio’s Adventures, the André Gide novel that introduced the world to the idea of the acte gratuit, the motiveless crime; above all, the works of Nietzsche, which taught Leopold and Loeb that the superior man, the Übermensch, was not bound by conventional morality. These were the books that created the modern mind, with its constant temptation to nihilism, the belief that everything is permitted because everything in meaningless.

By taking that reasoning seriously, Leopold and Loeb seemed to present modernity with its own deformed image. In a strange way, their single crime encapsulates the moral anarchy that was responsible for so many millions of deaths, in war and revolution and Holocaust, during the 20th century. As in a laboratory experiment, they demonstrated on a small scale the forces that, unleashed, could destroy the world. Meyer Levin makes this suggestion repeatedly in Compulsion, his fascinating 1956 novel about the Leopold and Loeb case, which has just been reissued by the enterprising new Jewish publisher Fig Tree Books. “It always seemed to me a telling part of this tragedy,” muses Sid Silver, the newspaperman who narrates the book, “that the victims were somehow external to it. … In the world as I was to come to know it, the victims mattered very little.”

Levin was particularly fascinated by the Leopold and Loeb case because he was so close to it: Like the killers, he was a precocious Jewish student at the University of Chicago, and he helped to cover the case as a young reporter for the Chicago Daily News. When he came to write Compulsion more than 30 years later, Levin drew on his memories to create the character of Sid Silver, an eager young apprentice reporter who is simultaneously thrilled and appalled by the cynical world he is entering. To heighten the stakes, Levin gives Silver a much closer connection to the crime than he himself possessed: Silver is a fraternity brother of Artie Straus, the Loeb figure in the book, and he shares a girlfriend with Judd Steiner, the Leopold figure.

Steiner and Straus themselves, however, are about as close to their originals as they could possibly be. Almost every detail of the actual crime finds its way into Levin’s retelling. Steiner and Straus lure their victim, here named Paulie Kessler, into their car and kill him with a chisel, then dump the body. They invent a complicated, multistage ransom scheme, hoping to extort money from the boy’s rich family, a plan that goes awry when the body is unexpectedly discovered. And they are exposed when Steiner’s glasses, accidentally lost near the body, are traced back to him through the manufacturer. All these things also happened to Leopold and Loeb, as did the dramatic trial in which the killers were represented by Clarence Darrow—renamed Jonathan Wilk in the novel—who successfully pleaded for them to be spared the death penalty. (Indeed, in his preface Levin acknowledges that he assigns Darrow’s actual words to Wilk.)

On one level, then, Compulsion works as a true-crime account of a case whose details are no longer as familiar as they used to be. The novel’s first section, tellingly titled “The Crime of Our Century,” opens on the morning after the murder, with Steiner and Straus trying and failing to put their overelaborate ransom plan into action. The killing itself is revealed only gradually, in a series of flashbacks, and Levin never gives us a straightforward picture of what happened. (As in the real case, for instance, it remains unclear whether Steiner or Straus actually delivered the fatal blows.) This narrative technique helps to impart some suspense to a story whose conclusion is known in advance: There is never any doubt, for a reader who knows the outlines of the Leopold and Loeb case, about whether the boys will get caught in the police net that slowly tightens around them. The same holds true of the second half of the book, which focuses on the trial—actually a sentencing hearing, since the culprits pleaded guilty—in which the fate of Steiner and Straus is decided.

Plot, however, is not Levin’s central concern, and the real source of the novel’s power lies elsewhere. Levin’s goal is to view a familiar story through a new imaginative lens, provided by Freudian psychoanalysis. Freudian ideas, which were just becoming fashionable in 1924 when the crime was committed, had become widely familiar and well-established by 1956, when Compulsion was written. In the process, those ideas were inevitably blurred and vulgarized, in part thanks to movies like Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound, which taught the public to see psychoanalysis as the search for a specific, all-explaining trauma in a patient’s childhood. (Hitchcock also made, in Rope, a claustrophobically thrilling version of the Leopold and Loeb story.)

That kind of mass-market Freudianism is the tool Levin uses to explain the “compulsion,” itself a Freudian term, that drove Steiner and Straus to kill. In the second half of the book, their defense lawyers commission a team of psychologists to write a report that neatly lays out Levin’s own psychoanalytic theory of the crime. We see how Straus, a charming sociopath, and Steiner, an arrogant introvert, were set on the course that led them to kill by childhood accidents and sexual traumas and family romances. Often the connection between these early experiences and the crime itself are cartoonishly literal: For instance, Straus uses a chisel to kill because, when he was a child, he heard a garage mechanic compare a chisel to an erect penis. Steiner pours acid on the dead boy’s genitals because he wants to erase his own masculinity and become a woman.

As this suggests, homosexuality, understood in classic Freudian terms as a blockage on the road to sexual maturity, is at the center of Levin’s understanding of the case. Steiner has an unrequited crush on Straus, which both binds them together and isolates them from their peers—Steiner is blackballed from the Jewish fraternity when rumors are spread about his trysts with Straus. Levin makes a point of showing that this crush is, however, a phase, the product of feelings of paranoia and mother-worship, which Steiner could potentially overcome through the love of the right woman. While this understanding of homosexuality comes across as outmoded and insulting today, it is nonetheless remarkable that Levin writes about the subject with such directness and sympathy. He even enters into Steiner’s sexual fantasies with a frankness that must have been surprising in 1956.

There is, of course, also another explanation for Steiner’s mutilation of Kessler’s body. In real life, Leopold said that he tried to destroy Bobby Franks’ genitals so that the police would not realize he was Jewish, which would help to trace his identity. In Levin’s hands, this practical explanation is also mined for psychological meaning. Judd Steiner’s “conflict over being a Jew” is related to Freud’s theory of Jewish self-hatred: “Every Jew had a wish not to be burdened with the problem of being a Jew. Then came the guilt feeling for harboring such a wish.”

Levin is not as interested in the Jewish psychology of the case as much as he is in its sexual psychology, but he does a good job of capturing the milieu of high-bourgeois Jewish Chicago, with its deep fear of bad publicity. “One thing is lucky in this terrible affair, Sid,” says the narrator’s father. “It’s lucky it was a Jewish boy they picked.” Indeed, had Leopold and Loeb’s victim been Christian, the murder could have become a different kind of archetype entirely, not a modern thrill-killing but an ancient blood libel. In many ways, Compulsion is a period piece, but its ability to communicate the horror of this famous crime gives it a lasting power.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.