The Mystery Stone

Does a rock in New Mexico show the Ten Commandments in ancient Hebrew? Harvard professor says yes.

Twenty miles south of Albuquerque in the Rio Grande Valley lies the town of Los Lunas, home to roughly 14,000 souls who tend to be religious but vote Democratic, and listen to country music but not Rush Limbaugh. Main Street coincides with Route 6, along which one passes the middle school, the Los Lunas Public Library, and the fire department. The biggest employer here is Walmart; the second biggest is a prison located at the edge of an empty field.

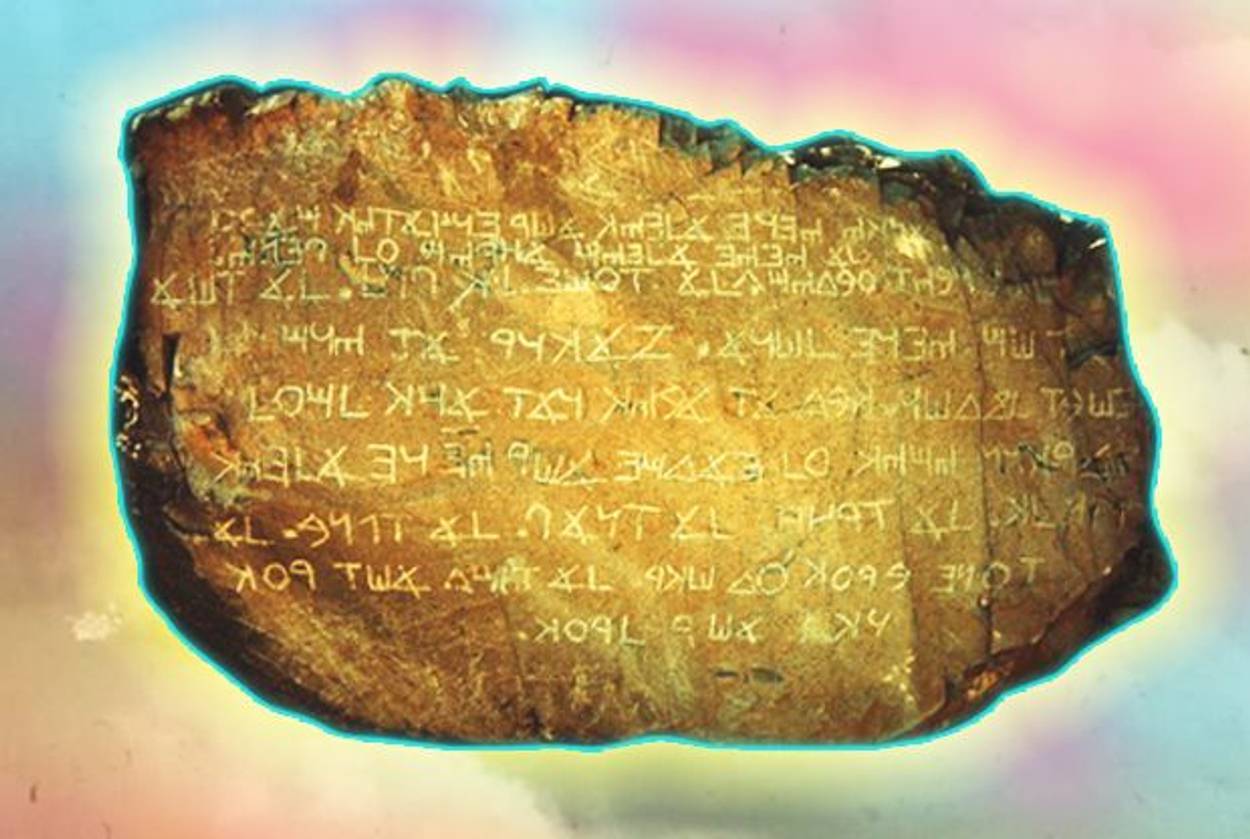

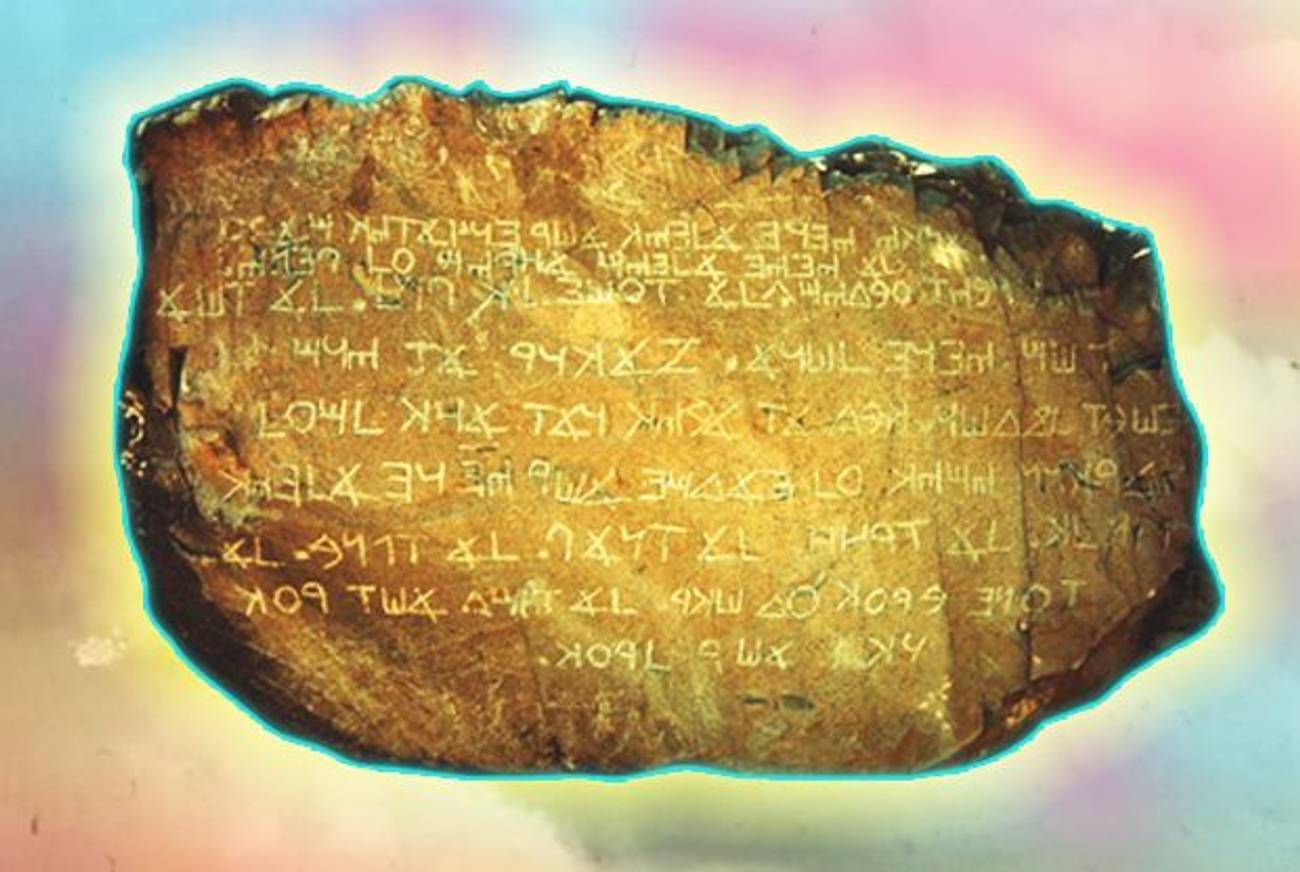

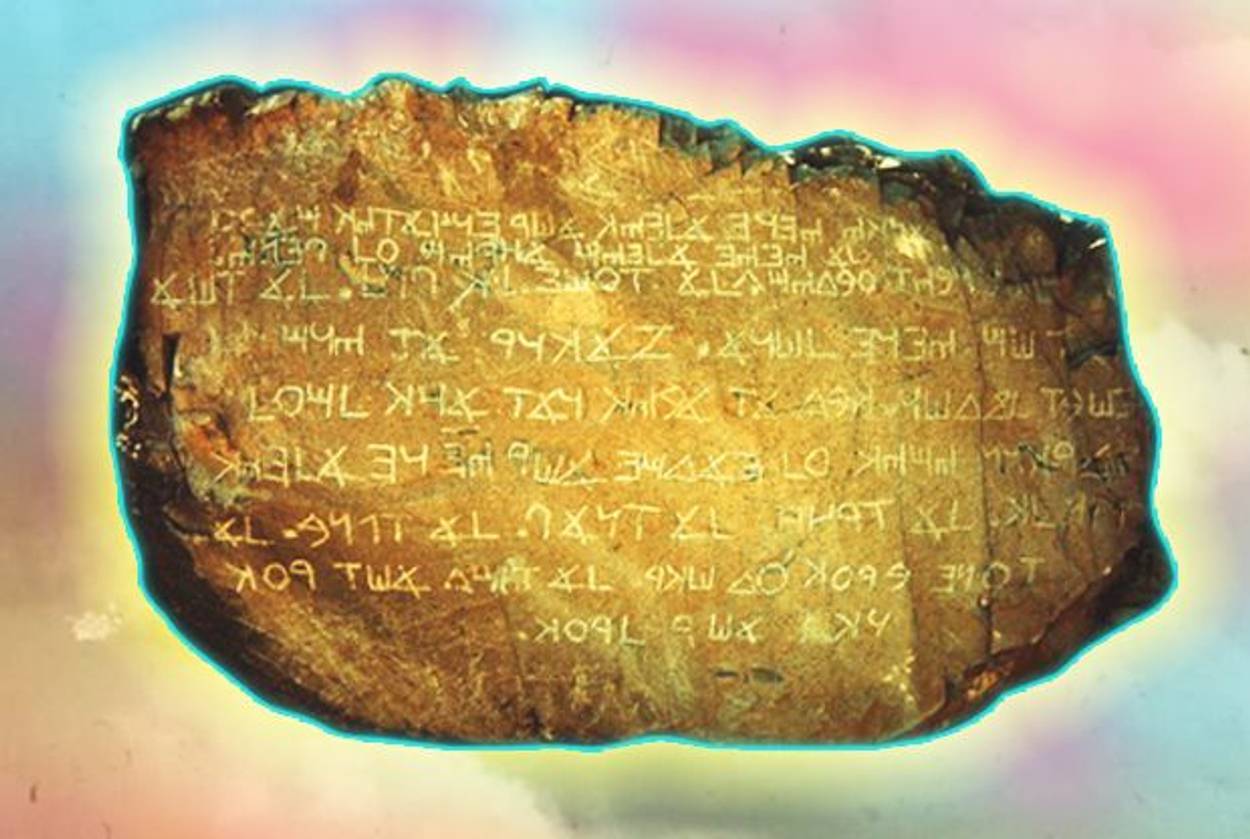

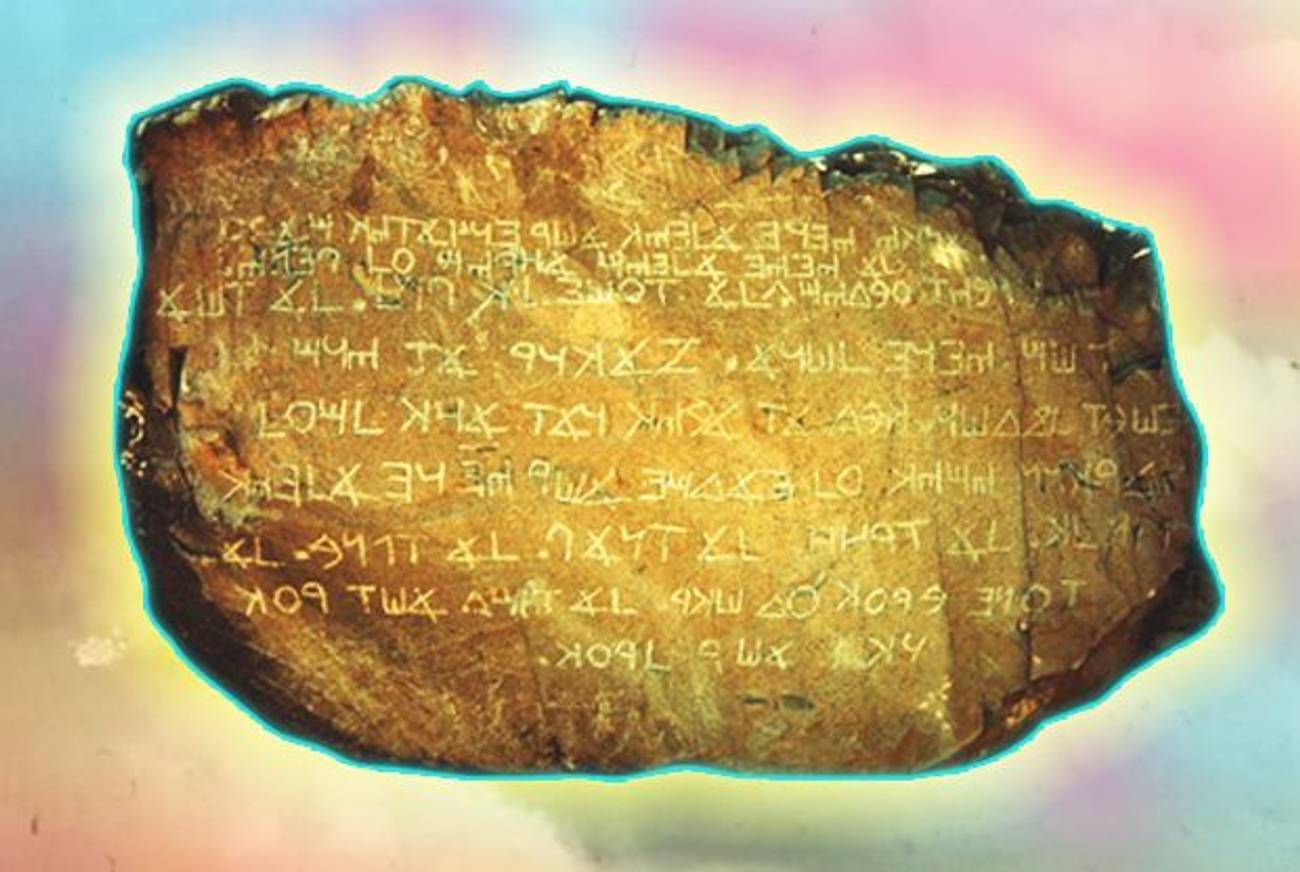

Los Lunas is also home to a curious artifact of mysterious origin: an 80-ton stone bearing a written code that is eight and a half lines long. The stone itself is about four and a half feet tall, its back end embedded into the mountain in the desert that is near the town. The characters etched into its surface are white, deeply engraved, and strangely geometric. They are chiseled in long, precise lines and seem to be grouped together in clusters resembling words. Every so often, a dot approximating a period appears after one of the clusters.

Who wrote this code in the heart of the Rio Abajo desert, and in what language is it written? For a while, the jury was out. Since the stone’s discovery in the 1930s, three different translations appeared. Robert Hoath La Follette, a lawyer and dabbler in archaeology, suggested that the inscription is a combination of Phoenician, Etruscan, and Egyptian letters that tell a halting, indeterminate tale of ambiguous survival and responsive weather: “We retreated while under attack … then we traveled over the surface of the water; then we climbed without eating,” he said it reads; “just when we were greatly in need of water, we had rain. … In the water we sat down.”

Dixie L. Perkins, another lay enthusiast, suggested that the inscription is an early version of Greek. Her translation is slightly more gothic: “I have come up this point. … The other one met with an untimely death one year ago; dishonored, insulted, and stripped of flesh; the men thought him to be an object of care, whom I looked after, considered crazed, wandering in mind, to be tossed about as if in a wind; to perish, streaked with blood. … I, Zakynerous, am dross, scum, refuse, just as on board a ship a soft effeminate sailor is flogged with an animal’s hide.”

In 1949, Robert Pfeiffer of Harvard’s Semitic Museum arrived in Los Lunas to inspect the stone. He concluded that it was written in a mixture of Moabite, Greek, and ancient Phoenician—an orthography that is basically Paleo-Hebrew, the script of the Jews prior to their exile to Babylon. There is even a debate in the Talmud as to whether the Torah that was originally given to the Israelites was written in Paleo-Hebrew or Assyrian, today’s Hebrew orthography. The alphabet continued to be used by Samaritans and was known by Irish theologian and scholar Henry Dodwell as early as 1691, who wrote in his A Discourse Concerning Sanchoniathon’s Phoenician History that “[the Samaritans] still preserve [the Pentateuch] in the Old Hebrew character.”

But it was Pfeiffer’s translation of the mysterious inscription on the stone that created the greatest interest among scholars and others: “I am Yahweh, the God who brought thee out of the land of Egypt out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven image.” The stone began to be referred to as the “Mystery Stone” or “Commandment Rock,” a title that gained further currency when The Epigraphic Society accepted Pfeiffer’s reading of the inscription as a truncated form of the Ten Commandments that, according to the Hebrew Bible, were given to Moses at Mount Sinai.

***

So, what explanation could possibly lead to the inscription of the Ten Commandments in Hebrew on a rock in the middle of the New Mexico desert? When I arrived in Los Lunas early one morning in February, I was told that the person to speak to about the Mystery Stone was Cynthia Shetter, the town librarian. “She knows everything about that stone,” said the receptionist at the Visitor’s Center, which is unusual: Very few people in town seemed to have heard of the stone, and no one I met had ever seen it. Shetter learned about the rock in her capacity as librarian because, as she put it, “a lot of people such as yourself were calling and coming into the library.”

Shetter is from a town south of Los Lunas originally called Hot Springs until its inhabitants voted to rename it “Truth or Consequences”—“after the game show,” she says. Shetter grew up on a ranch before becoming the “story hour mom” and then the chief librarian, and her cowgirl past is never far from the surface. She has an easy, unpretentious manner, is quick to laugh, and absorbs knowledge like a sponge. Throughout the day I observe her patiently waiting for various men to finish speaking and then subtly correcting them, in a tone of voice that makes it sound like she is agreeing with them. In her fifties, Shetter is still an attractive woman with long blonde hair and a twinkle in her blue eyes. She knows everyone and everything about Los Lunas and may well be the town’s next mayor.

She clears her schedule at the opportunity to take me to see the Mystery Stone. When I ask her who she thinks wrote the inscription, she smiles and says, “It’s a mystery.” She tells me that former mayor Louis Huning’s father, Jack Huning, remembers the stone as a child. The Hunings were German homesteaders who moved to the area in the 1850s, fleeing the German army. “Louis died last year at the age of 80,” she says. “So, that puts it way back in the 1920s or ’30s. And he says that he was shown it by an Indian sheep herder, who had seen it when he was a kid, so that’s back to the 1880s.” She shrugs and smiles, and says again, “It’s a good mystery.” Shetter seems proud of the stone for keeping its secrets.

Shetter buys water and Clif Bars, and we make the journey out to the Mystery Stone. Along for the ride is John Taylor, a former engineer who has written two books about the Civil War in New Mexico and is now working on a book called Murder, Mystery and Mayhem in the Rio Abajo. Well over six feet tall, with a deep, booming voice and big gray eyes, he has never seen the stone before.

There are many more mysteries in the Albuquerque area than just the Mystery Stone, Taylor tells us as we turn off Route 6 and onto the dirt road that leads to the stone. For example, when the Franciscans came in the 16th century to convert the Isleta Indians who now live on the reservation just north of Los Lunas, it turned out that they had already been converted—they are said to have asked the friars for sacraments. So, who had converted them? Sister Maria de Jesus de Agreda, the legend held, a Franciscan nun who lived in Spain and had never traveled but who had appeared to them in a collective vision over 500 times and preached to them in their own language. There is also the fact, Taylor tells me, that Elizabeth Taylor’s third husband died in a plane crash not far from Los Lunas.

Mystery Stone lies at the foot of Hidden Mountain, so named by the Indians, though no one seems to know why. I had procured a permit from the State Land Office, but on the way, Shetter says she has to make another call to Martin Abeita (she pronounces it Mar-teen), the manager of Comanche Ranch, which now belongs to the Isleta Indians. We will be crossing Indian land to get to State Trust Land, she explains. “I once came out here with some folks from University of New Mexico and Martin came and shut us down. He was pissed,” she adds to herself, dialing. Her tone when she informs him that we are going to be on Indian land is exactly the one I would have used: firm, but conciliatory.

The gate that leads to the Indian Reservation land is located square in the middle of the desert, 16 miles west of Los Lunas. The day is chilly, despite the sun. The ground is yellow, covered in a thick brush of thistles and sage bushes. To the east and west, red mountains erupt from the landscape in clusters. Hidden Mountain is a mile high.

“See that?” Shetter points to another mountain, lower than Hidden Mountain and to the east of where we are standing. I shade my eyes and look. “That’s Pottery Mound. It’s an ancient Indian site. No whites can go there anymore, since UNM returned it to the tribe. That was Abeita’s doing. I’ve been in this town 25 years and I’ve never seen it.”

We begin the mile hike to the base of Hidden Mountain. I ask Taylor who he thinks is responsible for the engraving. He is of the opinion that the inscription was a hoax perpetrated sometime in the 1930s. I ask him if he thinks that Jack Huning was lying or mistaken when he said it had been seen as early as the 1880s. He looks diplomatically at the ground and smiles.

“The groups who advocate for the ancient solution are mostly the ‘Young Earthers,’ ” Taylor says, referring to those who believe they can prove scientifically that the earth is only as old as the Bible claims. “They are committed to Biblical Inerrancy, which is dangerous, because it means that if one thing is found to be incorrect in the Bible, the whole thing becomes worthless.” I ask him if he is a religious man, and he says, “I am a Catholic, but I am a scientist by training. I don’t need the Bible to be true literally. ‘Myth’ is a loaded term, but I believe the Bible has stories meant to suggest the relationship between God and men, to guide us morally and ethically. To me that’s just more satisfying; otherwise, it’s a house of cards just waiting to collapse.”

“And besides,” Shetter muses, “who knows how long a year is to God? Here’s the stone,” she says quietly, pointing.

***

Many ascribe the first mention of the stone in print to the late Frank C. Hibben in 1933, though no record exists of his having published anything on the subject. Hibben was a famous mid-century archeologist who married into money and had a reputation for being an astoundingly charismatic professor and gaming enthusiast. But his reputation for being the life of the party was finally outweighed by his reputation for “salting” his sites—adding or antiquating materials, or misrepresenting the process of excavation, or the state of the artifacts he discovered. He was involved in the unfortunate Sandia Man affair, in which fraudulent salt was added to the Sandia Cave findings to suggest ancient American inhabitants. As a result, when Hibben’s name is attached to an archeological artifact, skepticism rides high. But it seems a long shot from seeding a site to creating one wholesale. Could Hibben really have invented the site, as some skeptics believe?

Not all skeptics believe the inscription was Hibben’s doing. Some think it might have been the work of students of his, trying to either help him or make a fool of him. Still others believe that it might have been the work of a 19th-century Mormon Battalion in the Spanish War, trying to drum up evidence for claims in the Book of Mormon that prophets lived in America until the fifth century. Alternatively, it is possible that the inscription is proof of a Mediterranean presence in the area, pre-Columbus—“America, B.C.” as one writer has called it.

Contrary to what one might expect, the debate about the rock’s authenticity does not rage but rather whispers along. No comprehensive archeological excavation of the area has ever been performed. The site doesn’t have an official name; it is referred to as “Decalogue Stone” and “Commandment Rock,” as well as “Mystery Stone” or “Los Lunas Stone” and to some as simply “Inscription Stone.”

Of the archeologists who have spoken or written about the site, the question of its authenticity seems to hang on whether a context exists for such a finding. It is a truism that in archeology, context is everything. “Nowhere in the history of the world do people leave one inscription and nothing else,” Kenneth L. Feder told me in a phone interview in January. He is a professor of archaeology at Central Connecticut State University and author of Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archeology. “Such people don’t exist,” he added emphatically. “I know what it looks like when humans live somewhere. It’s my trade. Archeological findings are accidental; it’s all about how traditions become evidence. If people lived here, where’s their garbage?” He ended in a crescendo. He is a man used to speaking publicly about such things, with an IMDB page that boasts appearances on TV shows called Is It Real? and History’s Mysteries. When I asked him why others are so ready to believe in the possibility of pre-Columbian non-Native Americans, he said, “It’s kind of a fascinating possibility, and scientists are humans like everyone else. Sometimes they check their skepticism at the door because they want something to be the case due to religious reasons. But I don’t have a holy book. I just have ideas.”

But there are those who think that a context does exist for the stone. James Tabor, chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, says that the archeological context is to be found at the top of the mountain, where there are the remains of dwellings and more Hebrew writings. The organization of the dwellings on the mountaintop plateau is reminiscent of Masada. But even more convincing to Tabor is the star map engraved on one of the stones that records a solar eclipse dated to Sept. 15, 107 BCE. That was the date of Rosh Hashanah of that year. All this adds up to a context compelling enough to rule out the possibility of it being a hoax, Tabor explained to me in a phone interview in February.

Tabor bases his opinion on the expertise of Cyrus Gordon, late professor of Near Eastern cultures and ancient languages at Brandeis and NYU. Gordon, who died in 2001, was greatly respected for his work in all areas save one. “His colleagues were very embarrassed that Gordon thought that ancient peoples visited the New World before Columbus,” Tabor tells me.

Yet Gordon did cite evidence for his claim. The Samaritans, who continued to use Paleo-Hebrew, had a special tax put on their ships, indicating that they were maritime and prosperous. Furthermore, the Mystery Stone is sized and placed appropriately to be a Samaritan mezuzah, which tended to be a large slab, rather than a small scroll, and was placed at the entrance to the town. As it happens, the Mystery Stone is located at the entrance to the only path leading to the mountaintop village. “The better question,” Tabor points out, “is why it is so odd to think that ancient people could have ended up in the New World in the thousand years between Solomon and the Common Era.”

After meeting Gordon at a conference at Harvard in 1995, Tabor made the trip to see the stone in 1996. During the trip, he spoke to Frank Hibben, who told him that an Indian guide recalled having seen the inscription as early as 1880. This suggested to Tabor that if it was a hoax, it was a 19th-century hoax, not a 20th-century one.

The story of Hibben being shown the rock by a guide is discomfortingly close to the one Huning told Shetter. Still, it seems a lot more likely that Hibben “borrowed” the story, than that he wrote the inscription.

Tabor published a paper on the Mystery Stone in David Horovitz’sUnited Israel Bulletin, but he has since retracted it, though he is still tentatively convinced that the site is ancient. “People tend to misrepresent things,” he says. I ask if he is religious, and he says, “Not in a way that is relevant.”

Interestingly, both those who think the stone is of ancient origin as well as those who think it is a hoax see the truth of the issue to be marred by a lack of objectivity in the scientific community. David Atlee Phillips, curator of Archeology at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology and professor of anthropology at the University of New Mexico, finds it much more likely that the inscription is the work of con artists than evidence of an ancient civilization. Preferring to communicate via email due to the “touchy nature of the subject,” Phillips writes, “As every con man knows, the essence of a good fraud is allowing the victim to believe what that victim wishes to believe. The ‘true believers’ I have encountered vis a vis the Los Lunas inscription fall into two categories. First, individuals for whom an ancient Old World inscription in the New World would validate their particular religious beliefs. Second, individuals who are looking to make the Next Great Scientific Discovery. Some humans are able to resist the temptation of the more self-serving path, but others are not—and once they are on that path, they use their certainty to determine which potential facts are correct and which are not. In my experience, once people have started down that path, they are quite impervious to whatever information I provide them.”

The smoking gun for Phillips is the “caret,” symbolizing a correction, a modern symbol. “I infer that the person who inscribed the words was not fluent in the language, but was working off a photograph or drawing and temporarily overlooked part of the inscription.” Furthermore, Phillips writes, “when you stand and look at the inscription, a glance downward will show the possible signature of the creators. There in the bedrock is inscribed ‘Eva and Hobe 3-13-30.’ There is an oral tradition at UNM that Eva and Hobe were anthropology majors who prepared the inscription as a hoax, and who were found out. They were told that if they ever did something like that again, their careers in the field would be over.”

When I press Phillips on the “touchy nature of the subject,” he writes, “It is touchy because there are people out there who want very, very much to prove that the inscription is ancient, to the point that they will use only the parts of what I say that fit their preconceptions.”

The same charge is leveled—this time, against Mystery Stone skeptics—by J. Huston McCulloch, a retired professor of economics at Ohio State University who has published on the subject of Hebrew inscriptions in America. While Phillips says he is too much of a scientist to believe in the stone’s authenticity, McCulloch sees the insistence on disbelieving the inscription’s authenticity as unscientific. “A scientist must follow the scientific method,” McCulloch told me in a phone interview. “We compare the theory to the data, and if it doesn’t match, we revise the theory, not the data.” But when it comes to archeological findings, especially those that seem to corroborate the claim that non-Native Americans lived in America pre-Columbus, he says, “Archeologists claim that the data is wrong. Each time something is found, they claim it is unique and thus discredit it for having no context. They did that with the Bat Creek inscription, and the Newark Stones, and now with the Los Lunas Decalogue Stone,” referring to other finds of artifacts of disputed origin.

McCulloch’s interest in ancient inscriptions began with his interest as an economist in congressional appropriations. Specifically, in 1881, Congress appropriated $5,000 to the Smithsonian Institution to conduct a “Mound Survey” for “ethnological research” that included the inscribed stones. McCulloch sees this not uncommon occurrence as a blatant attempt to keep the inscriptions from being viewed as Hebraic, possibly due to anti-Mormon sentiment at that time.

Indeed, Mormons would seem to benefit the most, ideologically speaking, from authenticated Hebraic inscriptions. But in 1953, I found out, a group of five archeologists from Brigham Young University in Utah made the trip to Mystery Stone and found themselves unconvinced. Among them was John Sorenson, who wrote a letter to the editor of the Mormon Sunstone Review in the 1980s stating that though the scientists were “quite thrilled at first sight,” he notes that “the surrounding petroglyphs … were heavily patinated, whereas none of the carvings on the Phoenician stone were thus darkened.” Welby Ricks, another of the Mormon archeologists, concluded finally in the 15th Annual Symposium on the Archaeology of the Scriptures at BYU that “the Ten Commandment stone found near Los Lunas, New Mexico, is a fraud,” and probably the work of Eva and Hobe, as late as 1930.

In a similar vein, when I contacted the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to ask about Mystery Stone, spokesman Lyman Kirkland told me, “The acceptance of scripture has always been a matter of faith. Personal testimony of the Bible or Book of Mormon is not gained by weighing its historical and archeological context, but by studying and living the truths and teachings found there.”

***

I have almost passed the stone without noticing it. Amid the rocks, in the shade of its own heft and the mountain behind it, stands the Mystery Stone, the engraved lines absolutely straight as if drawn along a ruler down the surface of the rock, which is tilted at a 45-degree angle. The stone is blanched (from being cleaned by Boy Scouts in the 1950s, Hibben told Tabor), making dating through the patina—the surface layer of the rock—impossible. The first line has been methodically scratched out, but the rest of the inscription is completely legible. I pull out the Phoenician alphabet that I brought with me knowing the site has no signs, and begin to write the letters in their Hebrew counterparts on a notepad. “Lo Yihyeh Elohim Aheirim al Pahnay …” A chill goes down my spine.

It is then that I realize the error—a spelling mistake—Panai, or before me, is spelled with an extra Hebrew letter Hei. It’s not the only spelling error. Zakhor is spelled with an extra aleph, and Sheker is spelled with a khaph instead of a kuf. All phonetic mistakes, misspellings made by someone writing from memory and sound, rather than someone transcribing from a text. Either that, or mistakes made by a very clever impersonator.

Later I ask Tabor if spelling errors are usually a sign of authenticity or inauthenticity. He says a forger would be careful to use the exact text for fear of being found out. The ossuaries he studies in Jerusalem are often marked with spelling mistakes, which indicate a non-professional, rather than a hoax.

Across from the Mystery Stone is another stone with Indian petroglyphs on it. These appear different than the carving of the Decalogue. There is no depth to the images; they appear painted onto the surface, rather than etched into the rock, though this is an illusion. I can make out a mountain lion with a very long tail, and what seems to be a sailboat on a river. They also point upwards, facing the sun, unlike the Mystery Stone, whose face is at a 90-degree angle to the ground and therefore in the shade.

We climb to the top of the mountain. Along the way, the graffiti “EVA and HOBE 3-13-30” appears two more times, inscribed but less deeply than the words of the Decalogue. Taylor and I float various theories again between us as though this time we might solve the mystery, our curiosity turbo-charged by the site. Shetter hikes beside us quietly. A hush has fallen over her.

At the top of the mountain, the remains of dwellings and lookout posts lie in squat circles of stones at the outer edges of the plateau: the village Tabor mentioned. Another rock has “EVA and HOBE” and some petroglyphs, as well as more Paleo-Hebrew. I pull out my alphabet and read out, “Yahweh, Elohim.” Though written in the same handwriting as the Decalogue, these markings don’t have the same depth. They look like the ancient petroglyphs, which give the illusion of being painted on the surface of the stone. They are in the sun.

***

Shetter and I wait for Abeita at the Los Lunas Chili’s at a corner table with bar stools (he has specified the table he wanted). He arrives in the biggest white pick-up truck I have ever seen and stalks into the restaurant like a moving mountain. He is wearing a silk purple kerchief tied around his neck and a purple paisley silk shirt under his Comanche Ranch vest. He is also wearing a black, six-gallon cowboy hat and dusty boots with real silver spurs on them. He is a handsome man with a face long and grim, which he wears like it is just another burden. When I shake his hands, they feel like leather. He orders a Coke and is brought two by a waitress who lingers nearby throughout our stay.

I ask him about the Mystery Stone. He stares at me.

“It’s a pain in my ass is what it is,” he says. “And it’s a fake. It’s a money-maker for the state. We’re gonna get that land back, and then no more trespassers and whatnot.”

Shetter sits quietly, says nothing, absorbs everything.

I ask how far back the Indians remember the stone.

“I’ll tell you what. You can ask my Uncle Joe. He’s working on the ranch.”

Getting into Abeita’s truck is like getting onto a horse. We fly through the desert at 80 miles an hour on dirt roads. It is calving season. Velveteen cows and their 2- and 3-week-old calves stand by the side of the road in groups, unperturbed by the truck. Abeita talks about the Tribal Council of 12 who are voted in by the people every two years. I ask if they campaign. “Kinda, sorta,” he says. “Basically, the people with the biggest family get voted in.” He talks about a calf that was born yesterday and jokes that it has Down Syndrome—“I don’t know what’s wrong with him! His face is all crooked,” he says affectionately—and about the two women who broke his heart. He repeatedly and patiently explains to me the ins and outs of land ownership in New Mexico—“We own 120,000 acres, from Isleta Pueblo near the airport all the way down toward Pottery Mound. We lease some more land for the grazing rights to 12,000 other acres—that’s where your stone is. But there’s also the water rights which run underground. Used to be all ranchers here. Now they’ve been moved out because of the water rights.”

He explains to me that Comanche Ranch was bought from the Hunings by the Isleta Pueblo for $6.7 million, with proceeds from their casino and an associated Hard Rock Café. Now the Pueblo is incorporated, which some support and some don’t.

On the way in to the ranch, we meet one of his employees, Francisco, who is Hispanic. Francisco asks me gravely, “Are you going to educate us about that rock?” Abeita laughs at him.

Uncle Joe is a short man with a deeply lined, weather-worn face and a quick smile. He asks me my name and makes a big show of giving up after no tries. “What language is that? I can hardly speak English and you want me to say that!”

I ask him about the Mystery Stone.

“Well? So what?” he says, shrugging. “We didn’t know it was there. If they knew, no one said. It was a secret.” The Indians’ Christian conversion had clearly not extended to caring about the stone. “Just like the Pottery Mound. They say it’s sacred. If it’s sacred, I got no business going up there.”

Abeita had gone to check on the calf and left Shetter and me to speak with his uncle. He returns just as Uncle Joe finishes complaining about women being allowed to vote and run for council. “It’s the white man’s way. They are too light on crime.”

“So, did you get what you needed?” Abeita asks me.

“Take me to the Pottery Mound,” I say.

“Absolutely not. No one goes up there,” he says emphatically, and then, sheepishly, “Five thousand dollars.”

But it’s no use—I have sensed the half-heartedness of his resistance. I let the sum reverberate for a beat, which is all it takes.

“Oh, get in the truck,” he grumbles, and we climb back in.

If the Mystery Stone is all Truth, Pottery Mound is all Consequences. The ground is littered with a mosaic of bits of broken pottery, dried lava, and the occasional arrowhead, interspersed with the bones of foxes and other small creatures. The pottery shards are painted in all colors with beautiful designs—black on white, green on white, black on red, dots along lines with the remnants of figures. The pieces are mostly the size of my palm, though some are bigger. The mound is split down the middle by a deep ravine, and along the ravine wall a long white object is visibly protruding.

If the Mystery Stone is all Truth, Pottery Mound is all Consequences.

When I get back to New York I will learn from David Atlee Phillips at UNM that Pottery Mound was an Indian village between 1350 and 1500. I will learn that the pottery is in pieces because given the available technology, whole pots were fragile. Phillips gauges the average lifespan of a pot to have been no more than a couple of years. A few years ago, Abeita found some uncovered bodies and demanded that the site be returned to the Isleta Indians. As for Eva and Hobe, no one knows what became of them. Inquiries came up empty at UNM, where, like in a ghost story, their names continue to float around.

But for now, I don’t know any of this. I know only that I am in a sacred place. I walk silently along the mound, picking up pieces of pottery and putting them gently down again. The sun is beginning to set in the west, and dried lava shimmers against the desert ground. I look over at Shetter, and she is walking quietly with the same palpable reverence she radiated at the Mystery Stone. Mysteries are not there for the solving. Her blue eyes look up at me in the dying desert light.

Back in my motel room off of Route 6, the question of who wrote the Mystery Stone resumes its subtle, persistent drumming. Images of Samaritan ships intersperse in my mind with Ken Feder’s theatrical voice, demanding to know of the theoretical American Hebrews, “Where’s their garbage?” The truth of Mystery Stone is obfuscated by the stakes of the mystery’s solution, the consequences of a non-Native, pre-Columbian existence in North America requiring too much belief for some and receiving too much skepticism for others. But if we can’t agree whether the Mystery Stone is sacred artifact or profane hoax, we can agree that our debates about what constitutes the sacred and the profane, the scientific and the belief-worthy, are sanctified.

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer who lives in New York. Her Twitter feed is @bungarsargon.