The Mythmakers

Rachel Kushner’s new novel The Flamethrowers is overly cool and stylish. So, why do the critics swoon for her?

When James Wood reviewed Rachel Kushner’s new novel The Flamethrowers in The New Yorker, he praised the book for its ability to transcend the usual binary opposition between realistic fiction and playfully postmodern fiction. Here, he argued, is a meticulously imagined historical novel, one that moves from the Italian front of World War I to the SoHo art scene of the 1970s, with a confidence clearly based on thorough research. Yet The Flamethrowers, Wood wrote, is so powerfully, even recklessly imagined that each moment lives like the present. For Wood, whose holy grail in fiction is the elusive but recognizable thing called “reality,” this makes The Flamethrowers a triumph: “[T]he novel’s reality level [is] as high and blindingly brilliant as the Utah sunlight.”

Wood’s rave, itself the holy grail for contemporary novelists, put the crowning touch on the series of glowing reviews and profiles that greeted Kushner’s second novel. Her first, Telex From Cuba, was already a critical success—it was a finalist for the National Book Award—but The Flamethrowers has achieved something even rarer: It has made Kushner about as famous as a literary novelist not named Jonathan Franzen can get in contemporary American culture. Especially notable has been the personal quality of this attention. Jami Attenberg’s The Middlesteins, published last year, was on the cover of the New York Times Book Review and reached the best-seller list; but Attenberg was not, like Kushner, profiled by the New York Times and pictured in Vogue.

It’s always fascinating to watch as the critical and publishing apparatus moves into action to anoint a new novelist. Why, hundreds of novelists must ask themselves, does one writer become famous, when others, perhaps just as talented, remain stuck on the midlist? In Kushner’s case, I think, part of the reason has to do with a different binarism than the one Wood identified—a conflict even more intractable than the one between realists and post-realists: the gender divide in contemporary literature.

In recent years, this has become a subject of intense debate. Earlier this month, I attended a panel at New York’s HousingWorks Bookstore titled “Sharp: A Discussion of Women and Criticism,” in which an all-star group of female critics discussed the state of their art. Among the issues raised were the so-called VIDA count, which has demonstrated in recent years that elite publications favor male authors and reviewers by a huge margin; and the gender-coding of book covers, a problem humorously highlighted by the Coverflip contest; and the split between commercial publishing, which markets primarily to women (often in the form of what some call, often disparagingly, “chick lit”), and prestige publishing, which continues to favor men. Some participants in the panel—in particular, Laura Miller of Salon—were impatient enough to suggest that “seriousness” per se is a male mode of writing and criticizing, a racket that mistakes humorless, self-aggrandizing pomposity for depth.

The novel that has waded most conspicuously into these roiled waters recently is Claire Messud’s The Woman Upstairs. Messud’s book, which I have not yet read, apparently features a furious and vengeful female protagonist, a fact that bothered a Publisher’s Weekly interviewer enough that she complained, “I wouldn’t want to be friends with Nora, would you?” Messud’s wonderful tirade of a response, in which she named literary characters who wouldn’t exactly make best-friend material—from Humbert Humbert to Raskolnikov—had a strongly feminist subtext, which was made explicit by many of the critics who wrote about the episode. Why should male writers be allowed to create monsters and anti-heroes, while women have to create friends and confidantes? Does the societal requirement that a woman be likable—read: inoffensive—extend even to fiction?

***

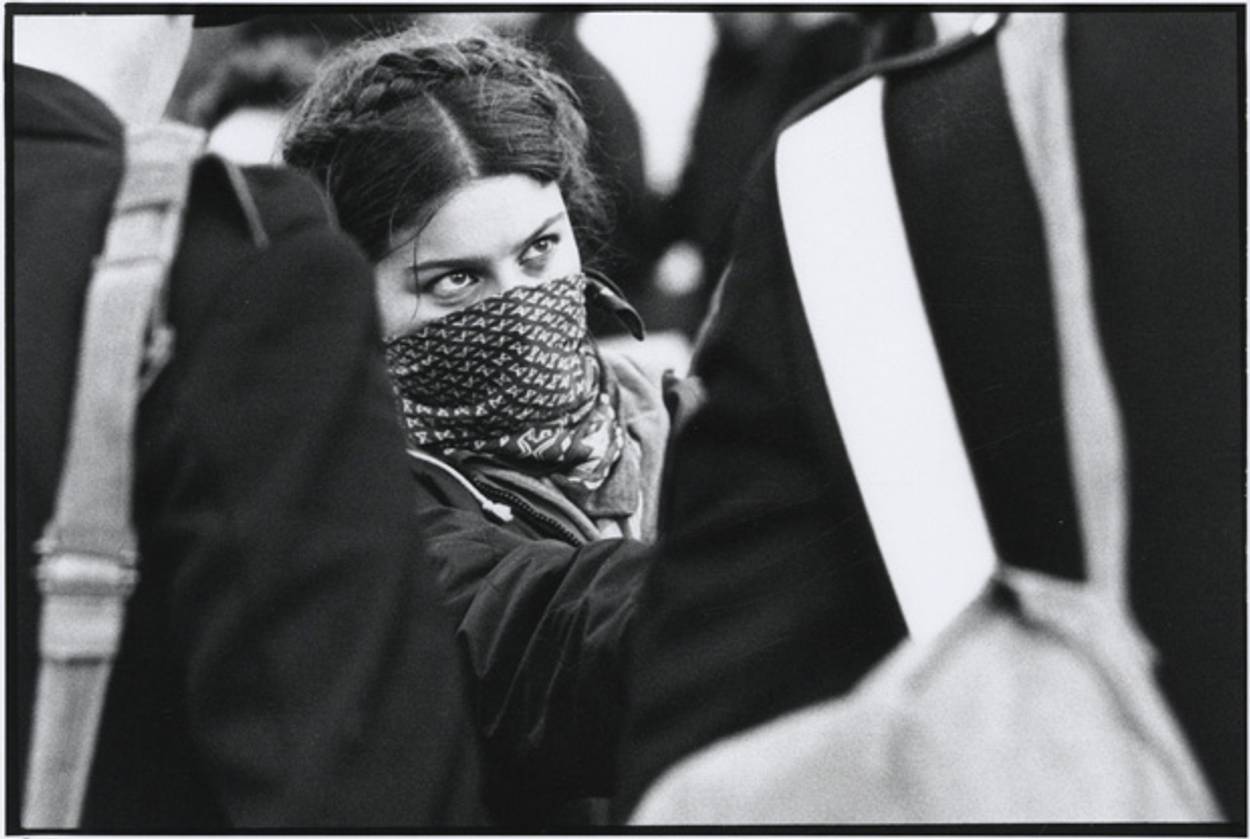

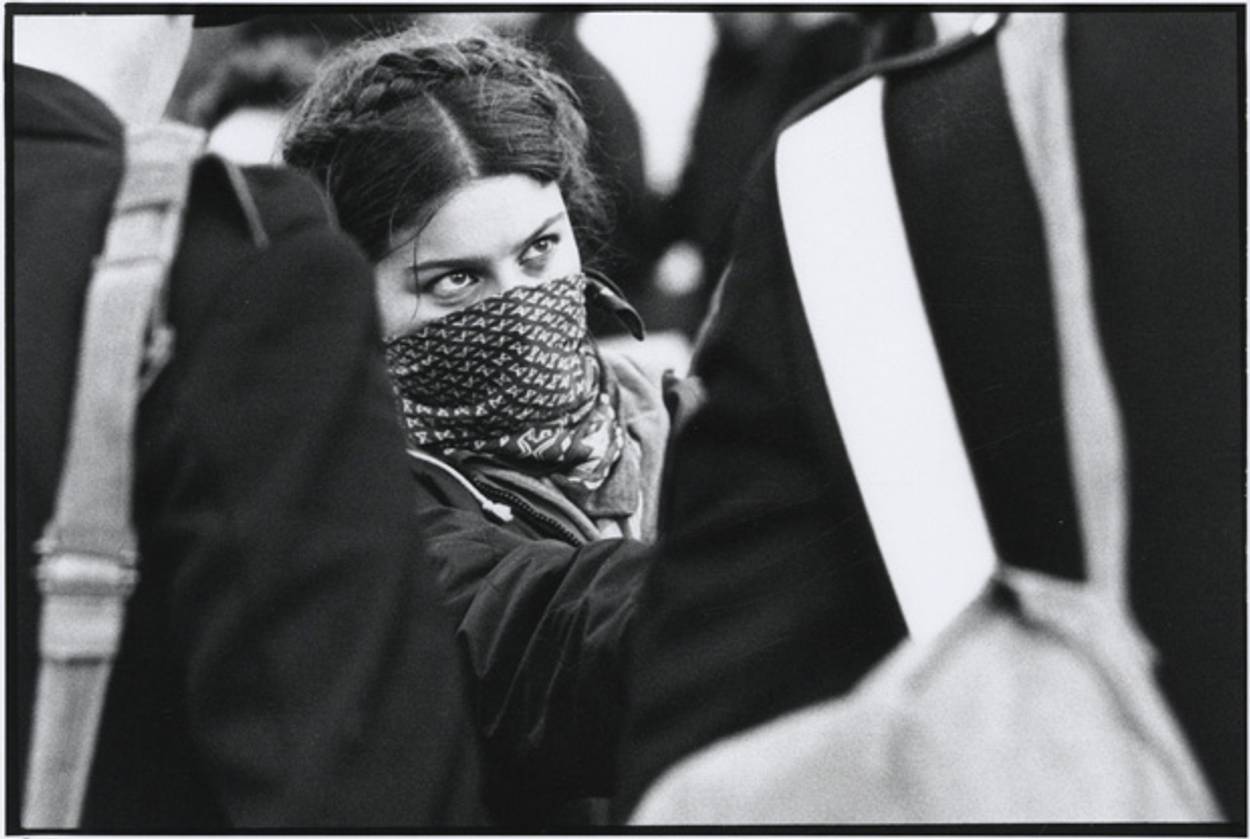

What makes The Flamethrowers a book for our moment is the way it implodes all the usual assumptions about what gender means in literature. Are “women’s novels” supposed to have robin’s-egg-blue covers and deal with domestic issues and personal relationships and offer likable protagonists? Well, the cover of The Flamethrowers features a tinted photograph of a woman with her mouth taped shut—an image taken from a 1980 issue of an Italian radical newspaper. It deals directly with the largest political issues, including futurism, fascism, industrial exploitation, and terrorism.

And at the book’s center is a female narrator—known only by her nickname, Reno—who is our window onto all kinds of male pretension and charlatanism. In a celebrated essay, the writer Rebecca Solnit coined the term “mansplaining,” after an incident in which a man began to lecture her about the photographer Eadweard Muybridge—about whom Solnit herself had written a book. In The Flamethrowers there is a similar episode, where Reno has to endure a lesson on skiing from an aging novelist, even though she herself is an expert skier. “He didn’t bring up skiing to have a conversation,” Reno observes, “but to lecture and instruct. I’d seen right away he was the type of person who grows deadly bored if disrupted from his plan to talk about himself.”

Monologuing is, in fact, the favorite activity of just about every character in The Flamethrowers. If Reno herself feels underdrawn, less than fully alive, that is because her primary purpose in the novel is to be an audience for the endless self-dramatizing performances of everyone she meets. Take, for instance, Giddle, a waitress in the diner where Reno takes to hanging out when she arrives, friendless, in mid-1970s New York City. “Giddle … was a waitress but also playing the part of one,” Kushner writes, “a girl working in a diner, glancing out the windows as she cleaned the counter in small circles with a damp rag. Life, Giddle said, was the thing to treat as art.” Giddle used to hang out at Warhol’s Factory, and if Warhol could make movies of people just being themselves, why couldn’t just living one’s life constitute a kind of artwork?

The art world is, of course, the perfect place to observe this kind of self-dramatization. Art, as Kushner describes it, is a confidence game in the strict sense of the word: To succeed, you must be confident that what you are doing is art and not just puerile gamesmanship. Sandro Valera, the Italian artist who becomes Reno’s lover, makes empty metal boxes; John Dogg, a minor character seen in passing, projects light onto walls. Ronnie Fontaine, Sandro’s best friend, is also an artist, but his real creativity is poured into the outrageous lies he tells about himself. Some of his shaggy-dog stories go on for pages, like the one about the time he got amnesia as a child and ended up as a wealthy couple’s cabin-boy on a cruise around the world.

For Reno herself, who has not yet discovered her voice as an artist, the vehicle of self-expression is just that, a vehicle—specifically, the motorcycle manufactured by the Valera company, of which her boyfriend is the unhappy scion. “There was a performance in riding the Moto Valera through the streets of New York that felt pure. It made the city a stage, my stage, while I was simply getting from one place to the next. … It was only a motorcycle but it felt like a mode of being.” One of the novel’s most vivid set-pieces involves Reno trying to set a speed record on her motorcycle, in the salt flats of a Western desert. She plans to photograph the tracks she leaves, turning the traces of speed into a kind of inscription.

What’s fascinating about The Flamethrowers is the way its interrogation of performance, of image-making, is entwined with its own commitment to performance. Just as much as any of the artists she mocks—or is it mockery?—Kushner is out to create a mystique, and her book is full of portentous atmosphere and self-conscious cool. In other words, The Flamethrowers manages to be a macho novel by and about women, which may explain why it has been received so enthusiastically by the critics. This is a novel that declares on Page 4 that “People who want their love easy don’t really want love,” and on Page 5, “That’s the funny thing about freedom. … Nobody wants it.” Such musings would sound best in the voice-over to a film, and The Flamethrowers is heavily indebted for its mood and imagery to the films of its period, many of which are name-checked (Klute, Zabriskie Point). The anomie, the political doominess, the stylish alienation—all of this reads “1970s” in marquee neon letters.

Kushner could not evoke all this so well if she did not buy into its mystique, at least imaginatively. She has a real gift for grasping the prose-poetry of ideologies, whether it is the art-ideology of SoHo or the left-wing violence of the Italian Red Brigades or, in the sections of the novel set around World War I, the right-wing violence of the Futurists:

They were smashing and crushing every outmoded and traditional idea, Lonzi said, every past thing. Everything old and of good taste, every kind of decadentism and aestheticism. … Lonzi said the only thing worth loving was what was to come, and since what was to come was unforeseeable—only a cretin or a liar would try to predict the future—the future had to be lived now, in the now, as intensity.

The plot of The Flamethrowers is alternately attenuated and supercharged, depending on where Kushner needs her characters to go. Much of the time Reno is hanging out in New York, drifting from rooftop party to art gallery to bar; then suddenly she is whisked by Sandro to his aristocratic family’s mansion in Italy; then she is hiding out with communist revolutionaries. She ends up witnessing both a political march in Rome and the 1977 blackout in New York, less for any compelling internal reason than because these are moments Kushner longs to evoke, to mythicize.

One of the greatest powers of the novel is the ability to penetrate the myths we make about ourselves

The first words the reader of The Flamethrowers encounters are the epigram, “Fac ut ardeat,” Latin for “made to burn.” This was, we learn, the motto of the Arditi, an Italian commando unit in World War I, in which Sandro’s father served. They also help to explain the title: The young in every age, the novel suggests, long to burn up and to burn things up, to be bright and vivid and violent. What is missing from The Flamethrowers is a sense of what all its characters are like when they are not aflame, not performing their selves but simply being. As a result, even Kushner’s critique of artificiality ends up reading like a celebration of it: The novel itself is, if not “mansplaining,” at least always insisting on its own mystique.

But a novelist should not be a mythmaker, not when one of the greatest powers of the novel is the ability to penetrate the myths we make about ourselves—to show how things really work, instead of how they claim to work. The Flamethrowers is too cool, too stylish; in this it resembles some of the most famous writing of the 1970s, including Robert Stone’s novels and Joan Didion’s essays. (Stone, in fact, blurbs the book). But in the gray work-shopped world of contemporary fiction, Kushner’s bold gestures and grand ambitions rightfully stand out. We read her the way Reno listens to the artists she meets—with pleasure, amazement, and not a little suspicion.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.