Here we are at a party at the art collector Ronald Penrose’s multi-level house on Downshire Hill in intellectual-bohemian Hampstead. It is late 1940 and the bombs are falling on London. Upstairs there is general nonchalance, drinking and dancing, and a modicum of canoodling. Down in the basement it is a different story; firemen move in and out from the garden, filling buckets from a sand supply, then rush to extinguish flames at the burning houses nearby. Meanwhile, in the basement’s dark corners, a general we-could-die-at-any-minute debauchery has taken hold. Oblivious to the entwined lovers, the firemen toil on.

These two anecdotes, recalled by Canetti almost half a century after the events that they depict, are characteristic of the sharp, vivid, utterly honest, and fascinating brief chapters that constitute Party in the Blitz: The English Years which is essentially the fourth volume of Canetti’s memoirs, while quite different in form and concentration from its rather long-winded predecessors.

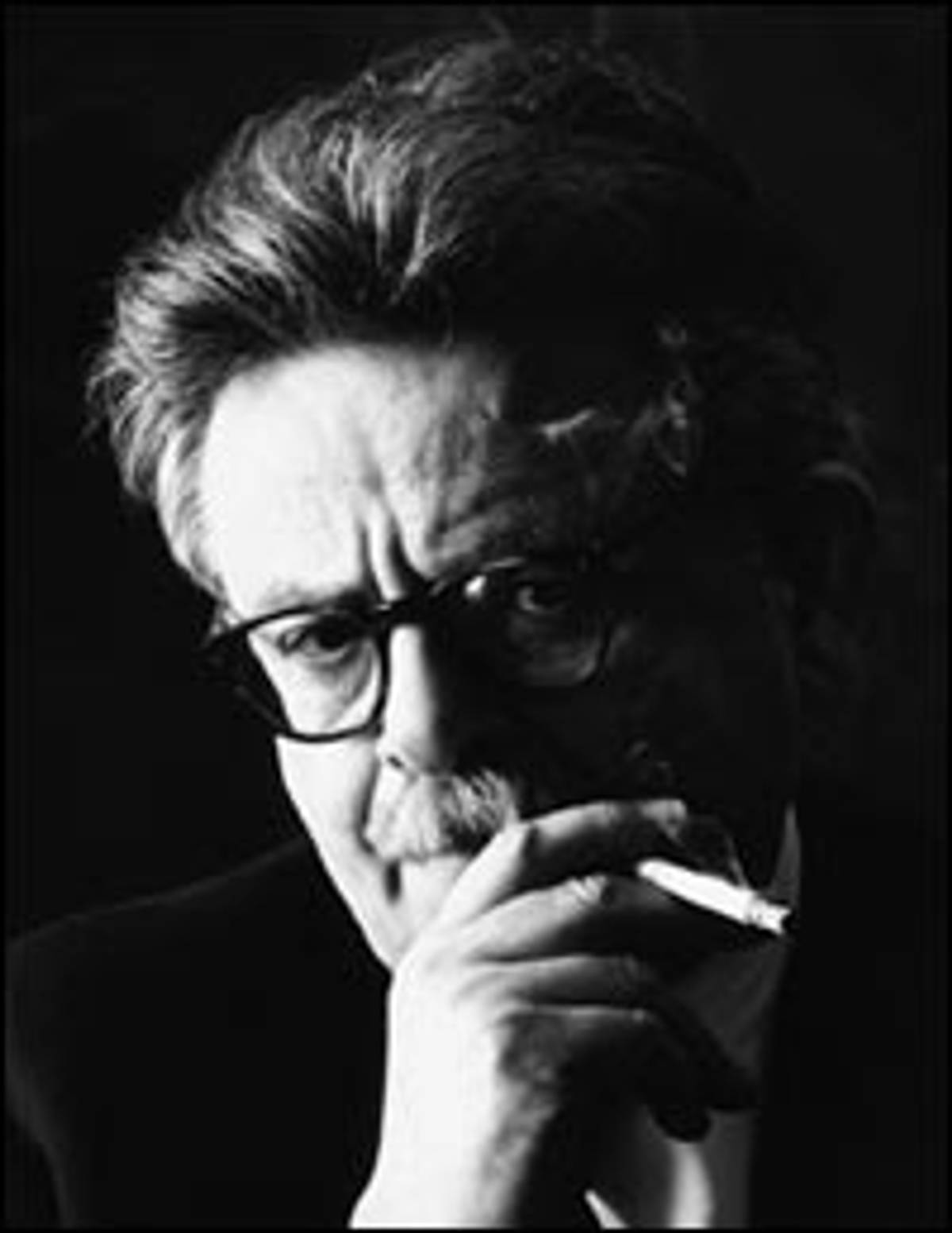

Of late, Canetti’s own party, on both sides of the Atlantic, has been a distinctly ill-attended affair. This is of a piece with the sporadic bursts of attention that have been paid over the years to this remarkable Bulgarian-born Jewish writer since his arrival as a refugee in London from post-Anschluss Austria in 1938. Canetti won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1981 which increased his celebrity, but only temporarily. Canetti wrote one great novel, Auto-da-fé, completed when he was 25, and one great anthropological-philosophical study, Crowds and Power, conceived in response to the mass pro-Nazi demonstrations that he had witnessed in Austria but not completed for almost 20 years. Canetti is a quirky individualist, close in some ways to Walter Benjamin, but where Benjamin’s truant Marxism has long made him a darling of the academic left, Canetti’s long volumes of memoir and short collections of aphorisms have not had a prolonged impact in literary-academic circles. This is a shame, as Canetti deserves close attention precisely because of the way that he bucks more or less all trends and resists most “isms.” He has no time for Freud (briefly his near neighbor in Hampstead) or any theory that appears to offer an airtight big-picture wrap-up of humanity.

Party in the Blitz caused a sensation when it first appeared in Germany in 1993, a year before Canetti’s death. (The terrific English translation by Michael Hofmann with an excellent afterword by Jeremy Adler is a first, and we should be grateful to New Directions for this publication.) It is in one aspect a biting indictment of the English literary-artistic world as he and his wife, Veza, a novelist herself, knew it during the first years of their exile in London and later during Canetti’s almost lifelong sojourn in the country. The English in general are condemned for their usual emotional failures—coldness and distance, as well as their snobbishness, arrogance, rigid caste-like hierarchical systems, “insipid conversations,” exclusiveness, suspicion of foreigners, and so on.

Then there are the creative individuals, English and otherwise, doing the rounds in wartime Hampstead and beyond: Iris Murdoch, Canetti’s lover for three years from 1952, gets absolutely and cruelly ripped, as a lover, as a novelist, and as a philosopher. (Peter Conradi, Murdoch’s biographer, reviewing Party in the Blitz for The Guardian has leapt to her defense: Canetti, he says, is an insignificant writer currently famous only for having had an affair with Iris.) Oskar Kokoschka is revealed as a narcissist. But the prime target of Canetti’s spleen is T.S.Eliot. Oddly, it is not Eliot’s anti-Semitism that enrages Canetti—indeed Canetti, whose antennae are usually receptive to loud and small noises alike, seems staggeringly unaware of British anti-Semitism in general—but rather Eliot’s dismissal of Blake and indifference to Keats. “I was a witness to the fame of T.S. Eliot,” Canetti writes. “Is it possible for a people ever to repent sufficiently of that?” This kind of literary rather than political animosity—Canetti is on the side of sanguine poets like his acquaintance Dylan Thomas—seems almost quaint to us now: literary fights, like the one over Russian prosody that ended the relationship between Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson, are surrounded by the aura of a gone world, one in which an individual’s opinions of books and writers really mattered.

What seems to have mattered above all to Canetti in his early London years (and plenty of his later ones as well) was the fact that nobody appeared to have any idea who he was. Only one man he knew—Arthur Waley, the masterful translator of Chinese poetry—had read (and admired) Canetti’s as-yet-untranslated novel, and while he quickly established a reputation as a brilliant thinker, his professional anonymity continued to trouble him. An ever-present at parties, he is frequently the odd-bod, everybody’s favorite refugee, a Central European intellectual with an untested literary pedigree and a vague reputation for something or other. A good listener who inevitably comes up with the to-the-point question, Canetti drew the attention of other fine minds, including Bertrand Russell and the composer Ralph Vaughn Williams.

It must have been frustrating for a man of Canetti’s intellectual stature—in pre-war Europe he had known Babel, Broch, and Musil—to experience the tolerant indifference of the British. To his credit, most of his portraits of the men who befriended him are without rancor or resentment of their ignorance. It is telling, however, that in Party in the Blitz Canetti reserves his most profound approbation for a humble street sweeper whom he comes to know during his and Veza’s period of evacuation to Chesham Bois, a small country village not far, but far enough, from the London bombing. With an almost Wordsworthian rapture Canetti celebrates this taciturn old man, who seems to represent the authenticity and wisdom that Canetti craves: “One day, when we had learned of the most terrible things, in incontrovertible details, he took two steps up to me…and said: ‘I’m sorry for what’s happening to your people.’ And then he added: ‘They are my people too.’”

Canetti and his wife had an open marriage, at least on his side, but you wouldn’t know it from Party in the Blitz; with the exception of Iris Murdoch, his lovers, like the novelist Friedl Benedikt and the painter Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, are presented with the same taxonomical distance as the other limned personalities. Canetti’s concern is less with personal relationships, or indeed with the daily tribulations of his own life—he and Veza were frequently on the edge of poverty—than with producing a kind of anthropology of his time and place. While, with Veza’s assistance, he worked throughout the war and on through the 1940s and 1950s on his magnum opus Crowds and Power—which begins with the bold statement, “There is nothing that man fears more than the touch of the unknown”—he was clearly thinking deeply about the social distances that surrounded him in London.

These distances hardly lessened as he grew older. While he maintained a number of friendships with British writers, like the Welsh-Jewish poet Dannie Abse, that are not recorded in this book, he remained something of an enigmatic figure on the London literary scene. Party in the Blitz concludes with some hostile reflections on Margaret Thatcher—Canetti, a lifelong pacifist, despised her Falklands war—and with a devastating list of the varieties of arrogance that he had come across in England: Oxford arrogance is at the top of the list. One can’t help but wonder why he stayed so long or why, even when he moved to Zurich in the mid-1980s, he maintained a home in England. And yet, despite the carping, there is much that Canetti finds to admire in England. Paradoxically, they are frequently the same things—for example, that stiff-upper-lip calmness in the face of crisis—that he despises.

When I was growing up in north London, the expatriate Central European community of my neighborhood generally headed for one of two well-known coffee shops: the Cosmo in Swiss Cottage or the Coffee Cup in Hampstead. Canetti liked to frequent the latter; for a number of years in the 1950s and 1960s, he held court there before a group of admirers. The Coffee Cup was also my hangout then, and it chastens me to think that I might have seen Canetti without having the faintest idea who he was.

Salman Rushdie was less ignorant. An admirer of Auto-da-fé, he searched Canetti out in Hampstead and learned from him. As he later remarked on BBC radio, “I decided that all I had to do was—like Canetti—to combine vast erudition and awesome intricacies of structure with a sort of glittering, beady, comic eye.” Party in the Blitz, a lovely series of lively, unyielding essays, won’t bring Canetti back into the public eye, even though it should. But then again, a few weeks ago I mentioned Salman Rushdie in a class that I was teaching—and none of the students, ages 19 to 22, had ever heard of him.

Jonathan Wilson, the director of the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University, is the author of, among other books, the Nextbook Press biography of Marc Chagall.

Jonathan Wilson is the author of eight books including the novel A Palestine Affair and a biography, Marc Chagall. He recently completed a novel, Hotel Cinema, about the unsolved murder of Chaim Arlosoroff.