Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Petition to God

A searingly personal, deeply moving prayer is discovered in the Nobel Laureate’s papers

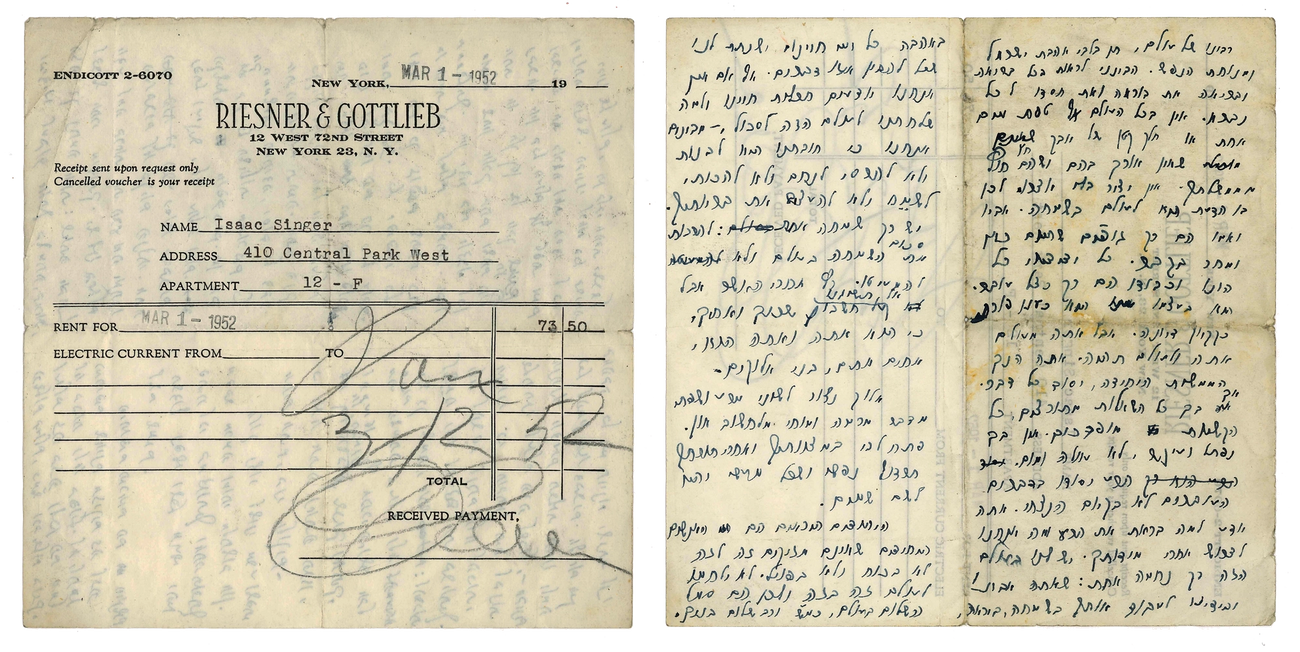

The prayer below was composed by Polish-born Jewish-American author Isaac Bashevis Singer (ca. 1903-1991), whose published work includes numerous volumes of fiction, essays, memoir, and stories for children. It was handwritten on the back of a rent receipt made out to Singer by Riesner & Gottlieb, which shows he lived on 410 Central Park West, Apartment 12F, and that he paid $73.50 for March 1952. According to the articles he was writing for the Yiddish daily Forverts in March, Singer appears to have been in Miami Beach, so it is likely that he used the back of this receipt some time later. On November 15, 1952, he published an article in the Forverts using one of his better-known pseudonyms, Yitskhok Varshavski, titled “Mentshn vos gloybn un mentshn vos tsveyfln” (People that Believe and People that Doubt, page 2), which discusses the faith of skeptics, a category under which he includes the Jewish patriarch, Abraham, whose brand of skepticism, he argues, created Judaism. The article ends with a personal credo: “Di elementn fun yidishkayt zaynen aynfakh: es iz a gloybn in an eyntsikn got un az der got iz in grunt gut un farlangt fun mentsh tsu zayn gut oyf zayn shteyger. Oyf di dosike aksiomen ken men boyen in yedn dor. Dos is der fundament, vos keyn shum vintn konen nit avekblozn” (The elements of Judaism are simple: it is a faith in a single God, a God who is fundamentally good, and who wants people to be good in their way. Every generation can be built on these axioms. It is a foundation that no winds can blow away).

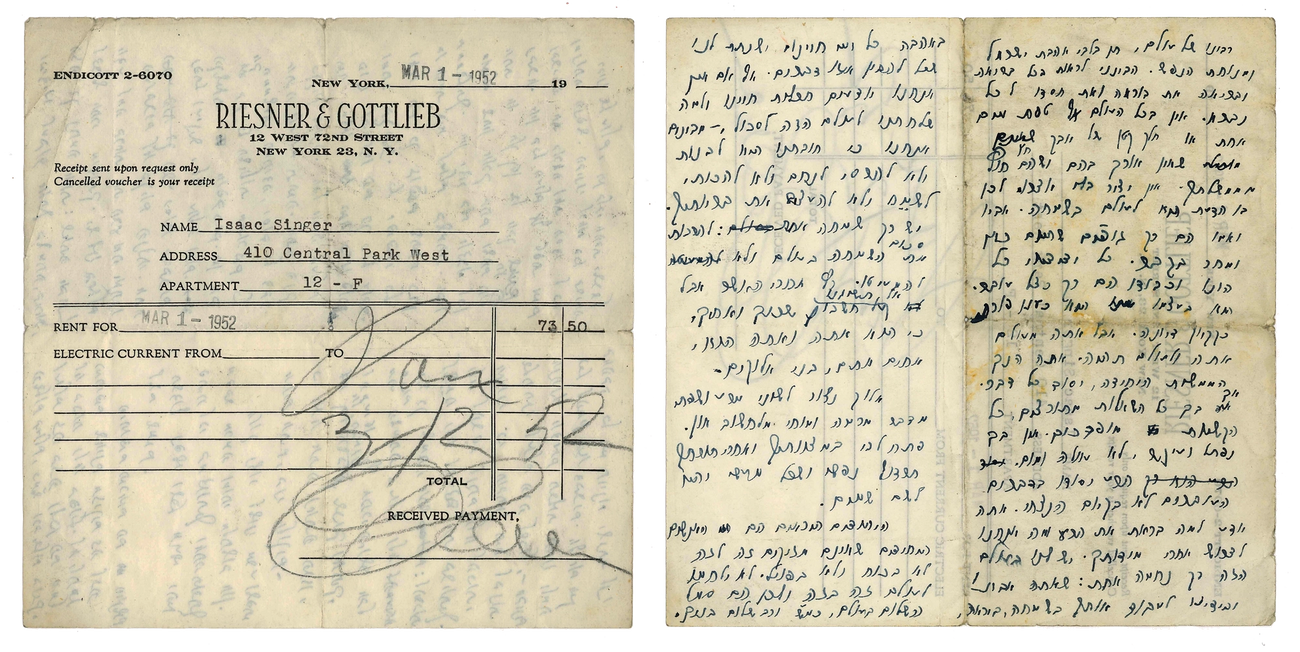

The prayer, written in Hebrew, appears to express a personal call to faith. It uses the language of Hebrew liturgy to lay out the foundation of a personal spiritual and moral basis. It is my speculation that this was one of a series of steps in which Singer slowly made spiritual tshuve, a return to religion, leading in 1955 to his memoir series about growing up observing his father’s rabbinical court in the apartment on Krochmalna Street in Warsaw—which first appeared under the name Varshavski in the Forverts, was published a year later under the name Bashevis as a book in Yiddish, and appeared a decade later in English under his full name as In My Father’s Court (1966). This prayer expresses a step in the formulation of Singer’s personal conception of religion—and the spiritual terms on which he based his writing. He would later formulate these ideas in a series of Yiddish articles—“A perzenlikhe oyffasung fun religie” (A Personal Conception of Religion, August 9, 1966), “Di getlikhe kunst un dos getlikhe visn” (Divine Art and Divine Knowledge, August 10, 1966), and “Mayn bagrif vegn got un di flikhtn fun mentsh” (My Concept of God and the Duties of Man, August 11, 1966)—which he presented, in English, in the spring of 1979 a lecture at the Gallatin Division of New York University’s series on “The Writer at Work.”

The text below reproduces Singer’s original Hebrew prayer in full – though minor stylistic edits were made to bring it more in line with modern Hebrew. As for the translation, I’ve kept as close as possible to Singer’s original, but took one liberty based on my familiarity with his work. Where, in Hebrew, he speaks of ha’yehudim ha’yera’im – God-fearing Jews—I rendered the phrase as “Those who fear God.” This is not merely in order to universalize the message, but also in the spirit of how the word Yid is understood in religious Jewish contexts—as “person.” As Singer writes in his essay, “Yiddish, the Language of Exile”:

I was brought up in an exceedingly orthodox home. My father was the rabbi in the Polish shtetl of Leoncin, where I was born. Later he became the head of a yeshiva in Radzymin, and still later a rabbi in Warsaw on Krochmalna Street. In our house, being a Jew and a person were synonymous. When my father wanted to say, “A person must eat,” he would say, “A Jew must eat.” It was not chauvinism as we understand it today.

In the religious Jew, Singer sees the symbol of those who understand that actions have consequences, and who believe that there is a higher power in the world that wants people to be good. As he writes in another essay, “The Jew, as seen by the Zohar, symbolizes the powers of goodness.” Singer’s religiousness was expressed as a unique conception of literature as mystical practice – yet, despite his documented skepticism, this prayer shows him at the age of nearly fifty in the midst of a personal and spiritual reckoning, putting his personal sources of faith into words.

David Stromberg, Jerusalem

Untitled (Prayer, c. 1952)

Isaac Bashevis Singer

Master of the Universe, fill my heart with love for my people, and rest for the soul.

Let me see the Creator in each and every creature, its mercy for each thing it creates.

There’s not a single drop of water or particle of dust in which your light is lacking, or that is outside your domain.

There is no creature without its creator.

Those who know this live always in joy.

Their parents are but bodies that are here today, and are tomorrow in their graves.

All their friends, all their possessions and honors, are like a passing shadow.

They are themselves like passing clouds, like Jonah’s tree.

But you – you have always existed and will always exist.

You are the only true being, the essence of all things.

Only for you are all problems solved, all challenges effortless.

There is nothing devious in you – no retribution, injustice, or fault.

Evil lives in all things temporary, not in what exists eternally.

You know why you created evil – and who are we to question your integrity?

We have only one comfort in this world – that you are our maker and that we have the power to serve you with joy, awe, and love, all our lives – and that you have given us the ability to understand such things.

Though we may not know the purpose of life, or why you sent us into this world to suffer, we understand that it is our duty to build and not to destroy, to comfort and not to torment, to bring joy rather than sorrow to your creatures.

There is only one joy: to increase and not to lessen the world’s joy.

Seek happiness, but not on account of your neighbors or family, for you are they and they are you, you are bonded, children of God.

God, guard my tongue from evil, my lips from deceit, my mind from sin.

Open my heart to your commands, let my heart seek your teaching, and let all my actions serve a higher purpose.

Those who fear God are the only ones who do not hurt each other, neither in fact nor in principle.

They will never wage war against each other, and for this reason they are the symbol of peace, as it is written: “and your children’s peace shall grow.”

“Prayer, circa 1952” © 2021 by the Isaac Bashevis Singer Literary Trust. Translation © 2021 by David Stromberg. Used with permission of the Susan Schulman Literary Agency.

Isaac Bashevis Singer (circa 1903-1991) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978.