The Tainted Bird

A new collection of Jerzy Kosinski’s interviews and speeches reveals an Everyman who worked on his own terms

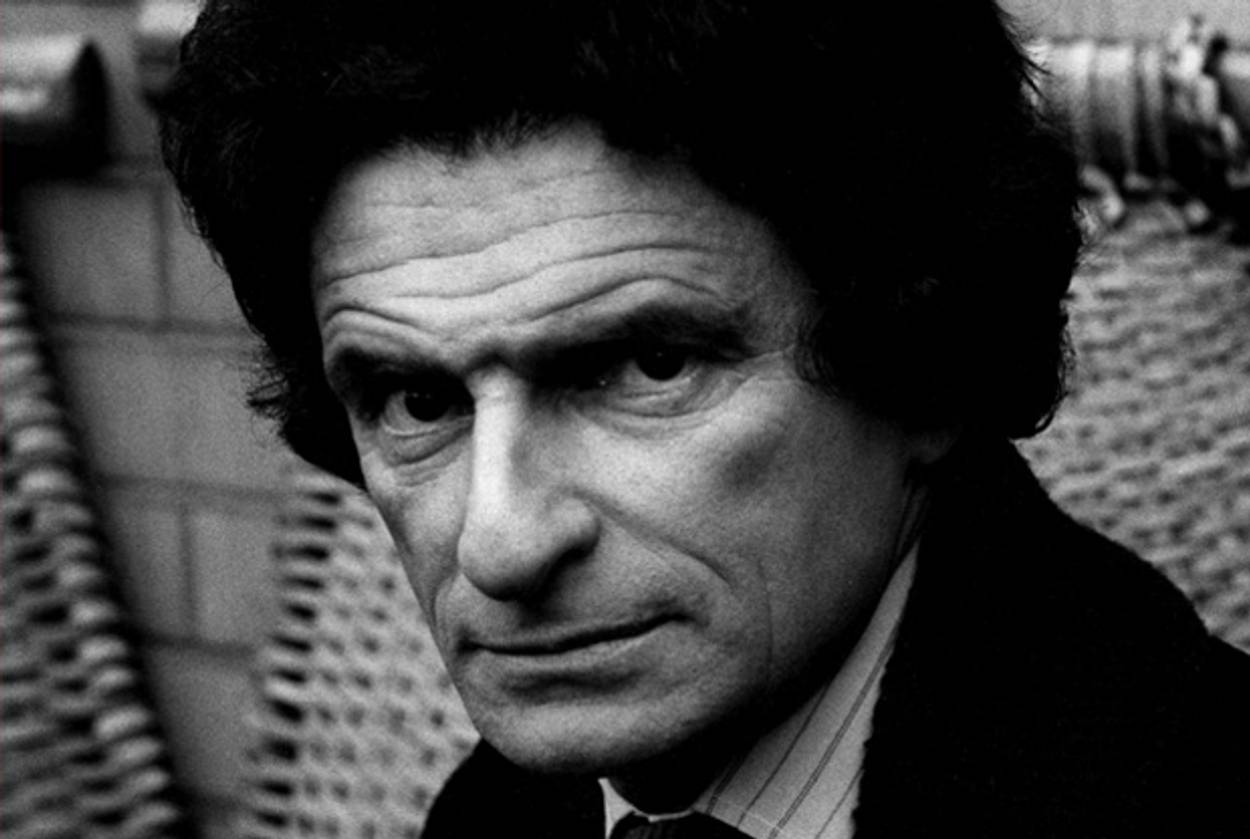

Jerzy Nikodem Kosinski was born on June 14, 1933, in Lodz, Poland, five months after Adolf Hitler ascended to the chancellorship of Germany. He died on May 3, 1991, in New York at the age of 57 after overdosing on alcohol and barbiturates and asphyxiating himself in his bathtub. To this day, everything in between is the subject of controversy.

Few legacies remain as mythic in scope and precarious in esteem as Kosinski’s. A Holocaust survivor living under various fake identities, he immigrated to the United States in 1957 and held odd jobs, like chauffeuring a Harlem drug king, until he married a wealthy steel heiress whom he later divorced. He was an actor, socialite, playboy, academic, and most notably an award-winning writer of books such as The Painted Bird (1965), Steps (1968), and Being There (1971), the last of which was adapted into an Academy Award- and BAFTA-winning film starring Peter Sellers and written by Kosinski himself.

He was also one of the most polarizing figures of the 20th century. Upon arriving in the United States, he explicitly denied being Jewish and used a nom de plume for his early, more overtly political writing. His fiction was frequently criticized as self-indulgent and vulgar. Accusations arose, most potently in a 1982 Village Voice exposé by Geoffrey Stokes and Eliot Fremont-Smith, that Kosinski plagiarized his novels, fabricated the verity of their autobiographical nature (specifically The Painted Bird), and used freelance ghostwriters (often uncompensated) to translate his books from Polish to English. And if that wasn’t enough, he shocked puritan American sensibilities, particularly American Jewish ones, with bold yet unsettling postulations during frequent media appearances. At one notable lecture, in which Kosinski addressed postwar Jewish self-victimization and what he called the “Second Holocaust,” he asked, “Must Dr. Goebbels succeed by injecting spiritual Zyklon B into the galaxy of the human mind where Jewish presence has been anything but marginal and nebulous?”

And while he certainly flaunted a charming personality, his life story is rife with unseemly anecdotes. According to biographer James Park Sloan, he was an angry child who often took out his frustrations on others, such as when he and a peer pushed a toddler down a steep hill in a baby carriage. He once received a letter from a reader that stated, “You’ve got to be one of the meanest little creeps on earth. My God, with all the suffering that you have said you have been through, you treat people like trash.”

Even after his death, Kosinski has failed to evade the ineluctable stream of detractors who believe him to be nothing more than a bloated, odious fraud. But Sloan, while at times an insufferably redundant and partial biographer, says it best when he concludes that Kosinski “lived in an aged of incongruities.” Kosinski himself is a living embodiment of said contradictions, and Oral Pleasure: Kosinski as Storyteller—a collection of mostly unpublished interviews and speeches compiled in part by Kosinski’s late second wife, Kiki—is a testament to his convoluted self. It both reinforces the myths of his life (since these are, after all, his words alone) and quiets them amid the clamor of his critics. While at times repetitive and confusing, occasionally cutting speeches into chunks running parts of the same speech in different sections to fit neatly within the book’s 16 thematic categories, it is nevertheless a most welcome body of texts that elucidates a rather mysterious persona.

***

Admirers and skeptics alike can agree that Kosinski experienced a lifelong struggle with reconciling the sacred and the profane, and that’s precisely what the title “Oral Pleasure” suggests. He once quipped, “Now I distinctly remember when I arrived in the United States, to me, oral pleasure meant Haggadah. … I mean the rest is pleasure, no doubt about it. But true oral pleasure comes from storytelling.” In order to even attempt to understand what drove Kosinski as both an artist and a Polish Jew who immigrated to postwar America, one must be willing to engage in this process of reconciliation as well.

Regarding Kosinski as artist, what he ultimately yearned for was authenticity. In his mind, the single most authentic force was “sexual instinct”—not sex, but sexuality, a wholly internal and spiritual force. As he explained to talk-radio legend Barry Gray in 1982, “To us, to my generation, to those good Jews brought up on the best of what’s in Judaic religion, sex was a rewarding and life-giving force.” The interplay between sexuality and spirituality permeates the National Book Award-winning novel Steps, where in one poignant episode, the narrator, a soldier, recalls a high-school girlfriend dumping him after he talked to a friend on the phone while they made love. “I told her it didn’t matter,” he comments, “but she insisted it did, claiming that if I made a conscious decision to have an erection, it would reduce the act of making love to something very mechanical and ordinary.”

This particular moment captures a genuine, rampant fear amongst sexual beings: the difficulty of understanding oneself as a lover, thus becoming unable to grasp the needs of one’s companion. But what continues to trouble Kosinski’s audience is the interwoven-ness of sexuality (a spiritual, procreative, God-given gift) with profane, graphic violence. In The Painted Bird, for instance, a promiscuous woman has a glass bottle filled with feces shoved inside her vagina, eventually killing her. Another scene from Steps depicts a peasant girl copulating with an animal, while men pay to watch the spectacle. Indeed, it’s not at all uncommon to find in Kosinski’s novels scenes of rape, incest, and bestiality.

Sometimes cheekily, other times in earnest, Kosinski dismissed accusations that such moments were the sum of his novels. He responded, rightly so, that deeply embedded in his work exists “a great deal of compassion—of being drawn to life, of protecting it, of defending oneself against bureaucracy, oppression, arbitrary imposition of someone else’s will.” His art, like life itself, is dramatic and unpredictable. But what it strives for, as epitomized by the protagonists of his earlier novels, is spiritual innocence. It’s about the protection of one’s inner being. As Sloan puts it, “Few writers had given more thought to the problems of the self—its boundaries, its divisions, its enemies, its very essence.”

Kosinski would likely agree with this estimation for many reasons, not least because in his later life he viewed Abraham Joshua Heschel as his “spiritual guru.” As peculiar as this may seem, Kosinski did evince a particular strand of Heschelian thought, that on the nature of the self. In God in Search of Man, Heschel maintains that the destiny of the self is “the concern for the non-self”:

There is no joy for the self within the self. Joy is found in giving rather than in acquiring; in serving rather than in taking. We are all endowed with talents, aptitudes facilities; yet talent without dedication, aptitude without vocation, facility without spiritual dignity end in frustration. What is spiritual dignity? The attachment of the soul to a goal that lies beyond the self, a goal not within but beyond the self.

Like James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, the burgeoning artist who “had been born to serve,” Kosinski approached writing as a vocation that transcends any single historical locus. His work extended beyond merely himself by spreading awareness of life’s complexities. He said in an undated interview, “I feel I have a responsibility to others, a responsibility to be engaged in the events around me.” Elsewhere he proclaimed, “My writing fiction is a very democratic process.” At once, Kosinski managed to place himself on a pedestal above all others while simultaneously pulling himself down. It’s an egalitarian disposition that channels the doppelganger narrator of Bruno Schulz—another Polish writer greatly admired by Kosinski—who opines, wistfully, “For, under the imaginary table that separates me from my readers, don’t we secretly clasp each other’s hands?”

Yet at the same time, Oral Pleasure shows Kosinski reluctantly conceding the limits of his reach. Echoing the newly retired Philip Roth, who now believes the novel’s readership (not the novel itself) is dying, Kosinski admitted that while his narratives were meant to connect with the public at large, he was destined to remain “a marginal writer who attempts to communicate with a marginal group of readers.” This is due in no small part to his self-proclaimed contentiousness. The writer’s main function, according to Kosinski, “is that of a detonator.” Only by determining what incites him, the writer, playing the role of “every man’s Everyman,” becomes an effective storyteller.

Kosinski’s claim to be an “Everyman” is precisely the problem. Beyond the more superficial provocations of his writing, there remains the nagging issue of categorization (fiction or nonfiction, novel or autobiography) that consumes and frustrates his readers. On the one hand, he claimed that his novels featured “archetypal characters and situations in an attempt to condense and crystallize situations common to all of us.” He chided that if he truly used ghostwriters, he would have produced a more extensive output. So, was it pure chicanery when he told Elie Wiesel, who reviewed The Painted Bird for the New York Times, that the book was essentially autobiographical? And was he being earnest or merely defensive when he claimed that “no text is ever completely original, because it is shaped by the ghostwriters who came before”? For a writer obsessed with authentic human experience, Kosinski strained mightily to muddle the distinction between fact and fiction in his own works. Or perhaps, as Sloan suggests, he gradually lost the ability to distinguish between the two.

***

This dilemma plays out rather saliently when considering Kosinski’s place as a Jewish writer and intellectual. His record of Jewish self-identification was rocky at best, but understandably so. Taken in by Polish peasants during the war (unlike the hero of The Painted Bird, he stayed with his family throughout the war’s duration), he grew up, on the one hand, concealing his true identity in order to survive. On the other hand, in the war’s aftermath, his father became increasingly outspoken about his Jewish pride, something the young Kosinski denied within himself upon arriving in the United States. Numerous American acquaintances initially thought he was either a gypsy or Polish Catholic, even anti-Semitic.

Kosinski did not publicly admit to his Jewish heritage until much later in life, and even then this information leaked out for a time unintentionally. Still, as alluded to earlier, Kosinski’s belated recognition of his Jewish selfhood put him in a unique position in relation to his American Jewish brethren, especially when it came to foretelling their woes. In a 1990 lecture at New York’s Congregation Emanu-El, Kosinski disparaged American Jews for allowing themselves to be defined by the Holocaust, thereby establishing a self-imposed ghetto instead of re-embracing “the Jewish ethos that celebrates life.” He added, caustically, that Jews “have chosen as their identity not their historical identity but an ID card with Auschwitz-Birkenau written on it in capital letters as large as we could possibly imagine.” In other speeches, he decried rampant anti-Polish sentiment within the Jewish community, arguing that rural Poles didn’t have to protect Jews during the war at all, given the consequence of death for doing so. At the time of these addresses—and even to the present day, one could argue—the Jewish community reacted negatively to his assessments.

Even if his words stung, they strove toward what Kosinski viewed as Judaism’s most beautiful and essential concept: the value of life. For Kosinski, the storyteller plays a critical role both to remember—“To a Jew,” he remarked in a 1988 address, “writing is essential to chronicling the past”—and to generate a sense of awareness. Episodic novels like The Painted Bird and Steps, which lack central plots in the traditional sense, crystallize the power of consciously experiencing each moment. He fled Eastern Europe for the United States to escape the former’s stifling forces of collectivization in exchange for the empowering individualism of American democracy, which enables each citizen to coexist with others while turning inward to discover what he finds spiritually meaningful.

This uplifting worldview turns rather sour in light of Kosinski’s gruesome suicide. A perennial enemy of passivity, he stated in a 1985 radio interview, “I see myself definitely as a participant in life because I love life, and I will be profoundly sorry when it ends.” But to what extent can his audience truly believe this? On the surface, there is something more sinister at play. To quote a chilling line from Steps, “When I’m gone, I’ll be for you just another memory descending upon you uninvited, stirring up your thoughts, confusing your feelings.”

Irrespective of the discrepancies between his life and fiction, between his inner storytelling gifts and uncredited stylistic assistance, his final deed constitutes the most haunting and troubling incongruity of them all. Paradoxically, it may also be the most fitting. By preventing an external force from shaping the contours of his life, he resembles the young protagonist of The Painted Bird who, after recovering from a horrific act of violence that left him mute, regains his agency and ends up “convincing myself again and again and again that speech was now mine and that it did not intend to escape through the door which opened onto the balcony.” Perhaps, in order to fully participate in life, Kosinski thought he must be willing to finish it on his own terms. It’s an act of twisted destiny that solidifies Kosinski’s status as one of modern Judaism’s most perplexing antiheroes.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Sam Kerbel has written for the Jewish Daily Forward, Kirkus Reviews, and Guernica, among other publications.

Sam Kerbel has written for the Jewish Daily Forward, Kirkus Reviews, and Guernica, among other publications.