The View From Here

Graphic artist Saul Steinberg spent formative years in Italy, a place that, like for other Jews, both sheltered and rejected him

Saul Steinberg’s Italian years—among the lesser-known periods of his artistic and human trajectory, and the subject of a series of lectures starting Monday at New York’s Centro Primo Levi—represent an emblematic story. Like thousands of Jews fleeing anti-Semitism in their countries, Steinberg found in Italy at first a welcoming refuge and later forced internment.

Steinberg’s artistic persona began to take shape in Milan, where he arrived from his native Romania in 1933 to study architecture. In 1936, he began contributing cartoons to Italian humor newspapers and soon became renowned for his visual wit. But, in 1938, with the institution of racial laws, he couldn’t believe “the betrayal,” as he put it. “Dearest Italy turned into Romania, hellish homeland,” he wrote in a 1995 letter to Aldo Buzzi. He then went through a bureaucratic ordeal to obtain the many papers needed to leave Italy. Following an aborted attempt to take the Portugal route, he was briefly interned, before managing to finally flee the country. He embarked for New York in 1941. The surreal documents contained in his masterpiece The Passport gain new poignancy in light of his struggle through the Fascist bureaucratic machine.

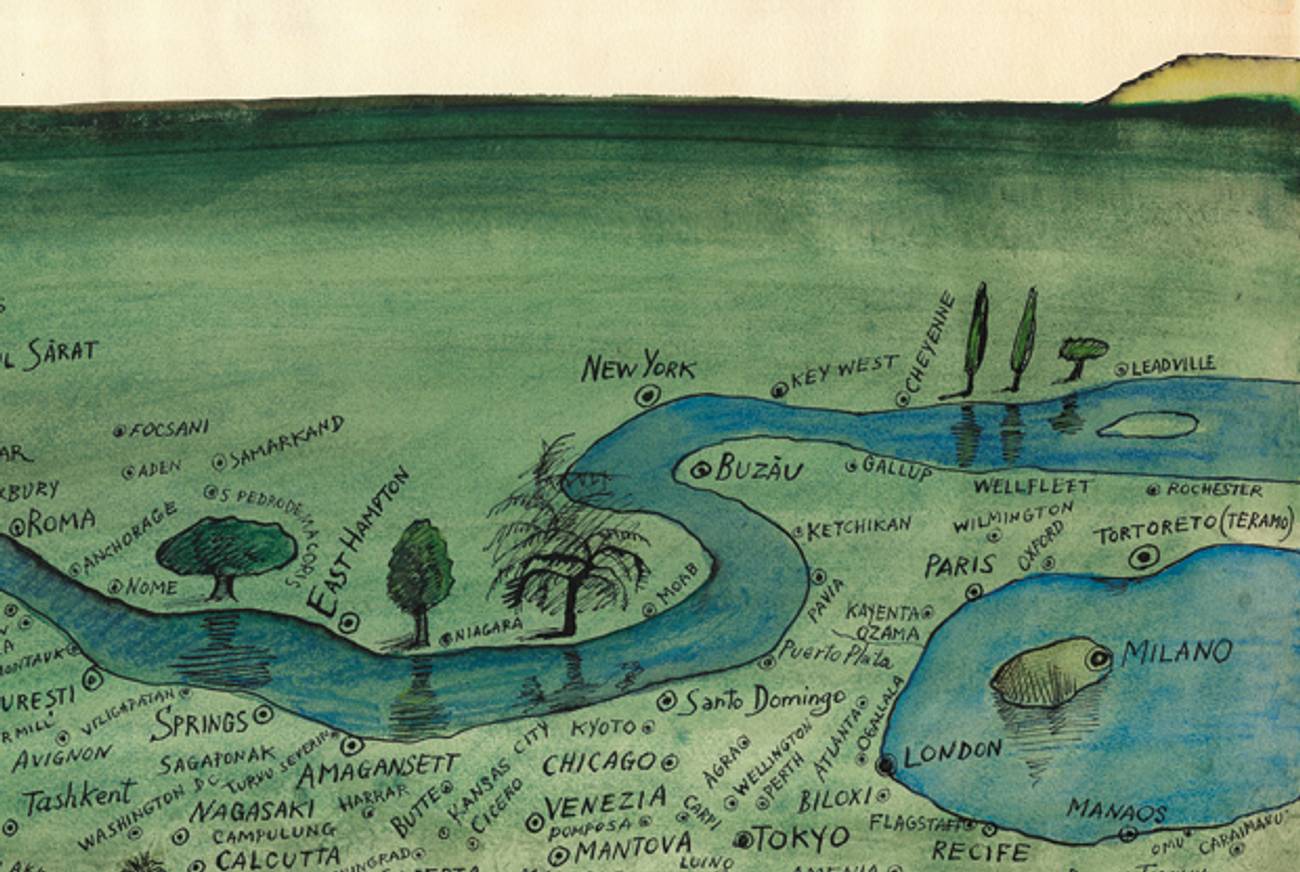

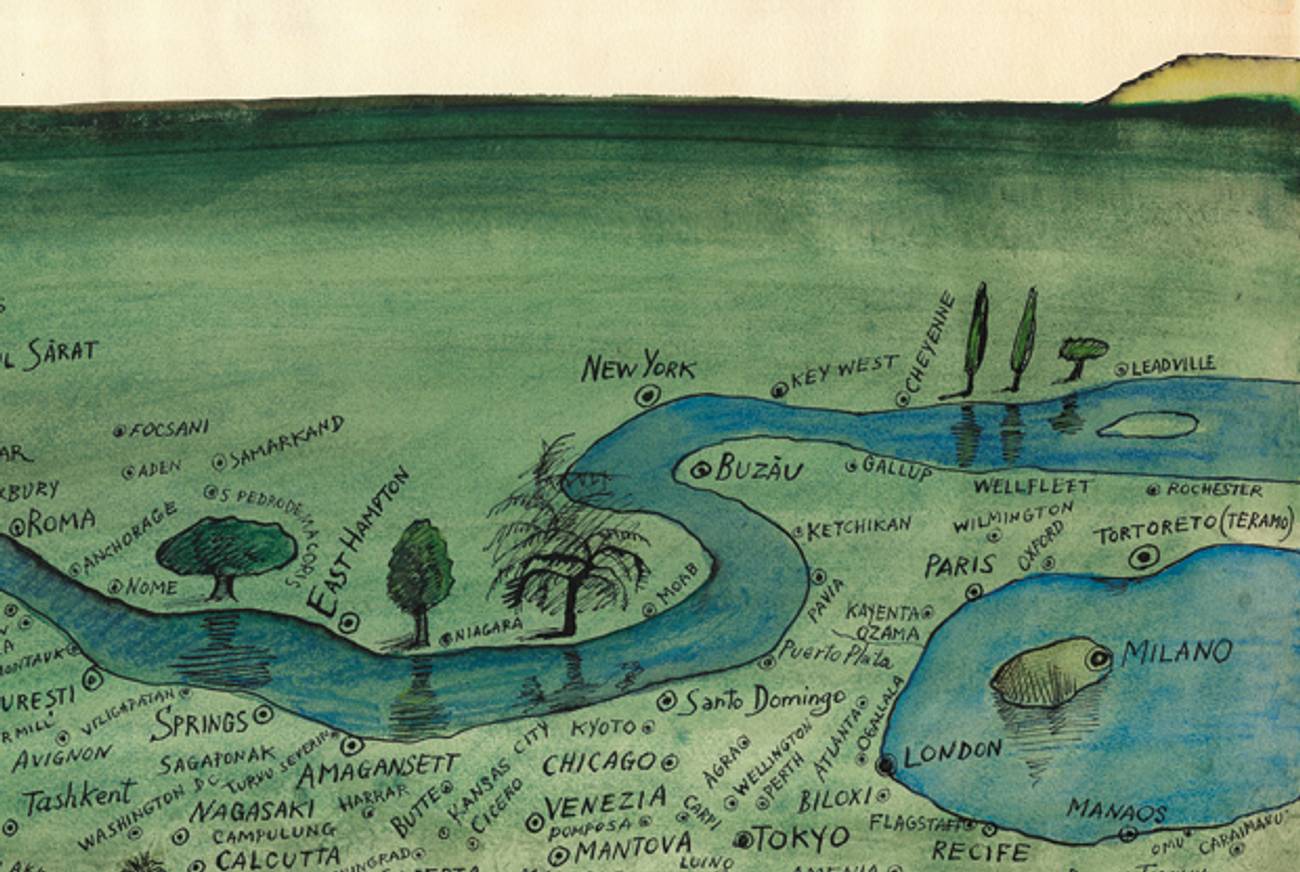

For most of his life, Saul Steinberg drew maps—maps of real or imaginary locations. Often the maps start with actual places, filtered through the artist’s mental constructs, as in his View of the World From 9th Avenue, the celebrated 1976 New Yorker cover. Another remarkable map is Autogeography, a bird’s-eye view of a green territory dotted with the names of places, from every corner of the world. As the title suggests, it is an idiosyncratic Carte du Tendre, where his birth place, Ramnicu Sarat, his beloved Milano, and Tortoreto, the place of his internment, coexist in close proximity.

Steinberg spent seven years in Milan, from 1933 to 1941; here he studied, loved, began to draw, and formed enduring friendships. The way it ended—his status returned to that of a “foreign Jew”—was an experience that would continue to haunt him for the rest of his life. But it never translated into a coherent narrative. Steinberg feared “autobiography—the last refuge of the scoundrel,” as he told Buzzi in a 1978 letter in the run-up to a retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York.

At the time, his comments on the Italian years were more provocative and concealing than informative. Still, his early cartoons bear great interest, as the Bertoldo newspaper and its artists managed to walk the thin line between compliance and satire, succeeding in sometimes mocking the pomp and pretentiousness of the Fascist regime.

Newly arrived in America, Steinberg had to explain to government officials how a Jewish artist had lived happily and worked successfully for newspapers in Fascist Italy. In the United States Steinberg began to work for the government. Assigned to the intelligence services, he was sent to China, India, Algeria, and finally to Italy, in mid-1944. This time he walked around Italy a free man, wearing a U.S. military officer’s uniform.

This essay was adapted and abridged by Alessandro Cassin, deputy director of Centro Primo Levi.

Mario Tedeschini Lalli is a director for innovation and development at Italy’s Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso.

Mario Tedeschini Lalli is a director for innovation and development at Italy’s Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso.