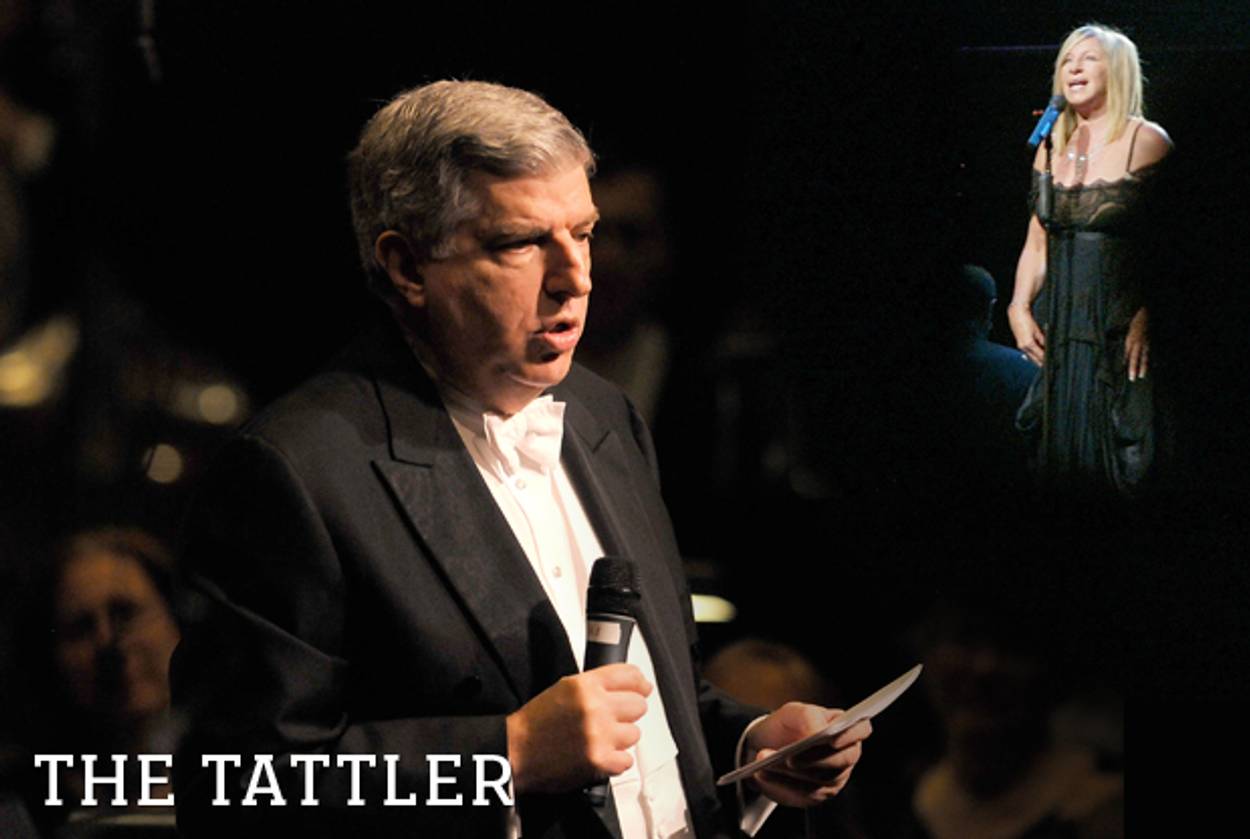

The Way Marvin Hamlisch Was

The son of Viennese refugees from Hitler, the gifted, menschy composer wrote the ultimate survivor’s song

Carrie Bradshaw and friends once asserted,just before dissolving into communal martini-induced weeping, that there are two kinds of women in this world: “simple” girls, and “Katie” girls. The “simple” girls, as personified in the episode by Mr. Big’s new fiancée (Bridget Moynihan, before she was jilted IRL by Tom Brady) are adoring, self-abnegating types who instinctively know how to position throw pillows and don’t ask too many questions and never forget to buy Windex. The “Katie” girls—so-called after the main character in The Way We Were, as played by Barbra Streisand in her most glorious stage as supreme deity to, in the words of Fran Drescher, all “Jewish girls in search of a leader”—are unruly, uncompromising, challenging, fearless; the kind of women who don’t let their partners easily win arguments or dictate their ambitions, who want to be the main characters in their own stories. If men—who conceivably range from shaygetz gods like Robert Redford with rumpled golden locks suitable for tender/inflamed mussing to the nebbishy bald guy your mother made you go out with over Thanksgiving—ultimately reject you, it’s not because of anything you’ve done wrong, but because the schmucks are simply scared of your Katie-girl wonderfulness. The lesson is clear: Different is nice, but it sure isn’t pretty/ Pretty is what it’s about.

And it all happened because Marvin Hamlisch wrote that song.

I’m a human being with thoughts and feelings and eyes and a heart, and, like all other such organisms, I can’t watch The Way We Were without crying my eyes out—and not pretty, demure, WASP-y crying either, but the deafening, ululating sobs of an ancient and tormented desert tribe, the kind my aunt is talking about when she tells the story of my grandfather’s funeral and how when they lowered the casket into the ground she “had never heard grown men scream like that.”

That doesn’t mean The Way We Were is a great movie. The story, ostensibly due to director Sydney Pollack’s demands that the male role be the equivalent in size and heft to the female one (a typical preoccupation echoed later in his work on the otherwise flawless Tootsie; i.e., it’s OK for a picture to have a feminist message as long as the main character is a man), has more holes in it than a needlepoint canvas, and on repeated viewings you start to get the feeling that the Katie character—in the grand tradition of Blanche DuBois and Samantha Jones—is actually an autobiographical stand-in for her male creator. It’s one thing to imagine yourself as a glossy-lipped Barbra Streisand in a series of fetching back-teased hairdos. It’s quite another to look in the mirror and see Arthur Laurents. For these reasons, I’ve always thought of the film as a sort of “problem play”: the Measure for Measure of the Linda Richman set.

But the title song elevates The Way We Were. The piece, with its demure opening chime soon taken over by Barbra at her soaring best, gives a period-specific and often melodramatic story a kind of nobility, a epic sense of timelessness. Hamlisch’s music and Alan and Marilyn Bergman’s lyrics allude to heartbreak and loss but are neither defeated by nor wholly triumphant over them. It’s not a question so much of banishing one’s demons as accepting them for having made you what you are; a wistful, bittersweet ambivalence that is no less powerful for being inconclusive; the kind of decision that, to borrow a line from Sondheim (who at 82, is still going strong, God help the person who has to peel me off the floor when he kicks it, they’re going to need a big, waterproof spatula) “is not to decide.” It’s precisely this kind of complexity that makes a Katie girl a Katie girl. Is it schmaltzy too? Sure. But so is love.

Of course, there’s also a larger, less romantic context in which to look at this, which is that in “The Way We Were,” Hamlisch, the son of Viennese refugees from Hitler, wrote the ultimate survivor’s song. Rare among the genre, it never trivializes the pain of the past. Instead, it gently, even lovingly, suggests that the pain is never really what’s important. It’s not about the broken heart; it’s about that single beautiful afternoon outside the Plaza Hotel when we pushed Robert Redford’s hair out of his beautiful face. It’s not about the blacklist; it’s about the belief that the world can be a better place. It’s not about the Holocaust, it’s about the fact that we were here at all.

So, go ahead. Have a listen this weekend and get nice and verklempt. (For those among you less sentimentally inclined, I suggest this inadvertently hilarious clip of Beyoncé serenading La Streisand at the Kennedy Center honors. I’ll give you a topic: Barbra is either hostilely amused or amusedly hostile. Discuss. And for all you Katie girls, say a little thank you to Marvin Hamlisch, who made the way we were the way we are.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Rachel Shukert, a Tablet Magazine columnist on pop culture, is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great. Starstruck, the first in a series of three novels, is new from Random House. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.

Rachel Shukert is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great,and the novel Starstruck. She is the creator of the Netflix show The Baby-Sitters Club, and a writer on such series as GLOW and Supergirl. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.