Theodor Herzl Is Alive and Well and Living in New York (Los Angeles, Paris, and London, too)

Unlike most of his learned Jewish contemporaries, Herzl understood that antisemitism can’t be pled or reasoned away

A few weeks ago, between watching thugs drive through north London shouting “F*** the Jews, rape their daughters,” and reading a tweet from an American TV personality with a pink bikini and 275,000 Twitter followers that read “These Jewish people are really killing children,” I picked up a vintage hardcover that was gathering dust at a lending library on a street near mine. This book was published in 1975 and set mainly in the 1890s, so I was surprised, upon opening it, to find … the present.

We’re in Vienna. The main character, Theodor Herzl, is a writer, a master of the German language, and a former member of a Teutonic college fraternity. He is a Jew by birth, but he’s over it. His son isn’t circumcised, and when a rabbi pays a visit to his home one December, the writer is just lighting the Christmas tree. He’s a proud citizen of a great polyglot power, the empire of the Habsburgs, where Jews are emancipated, fitting in tentatively, moving up conclusively.

Something is happening outside, a kind of unsettling buzz on the street. “It was easy at first to laugh it all off as a short-lived fad,” writes the book’s author, historian Amos Elon. “Many people succumbed to the temptation.”

Yet, the country is in decline, disintegrating into its constituent parts. The Austro-Hungarians are no longer in agreement over what “Austro-Hungarian” means, or who is included. There are Germans and Czechs and Hungarians and Poles, conservatives, socialists, anarchists—and then there are Jews, or rather, the “Jewish problem,” which suddenly becomes a burning preoccupation in Vienna and across Europe.

The prosperous Jews of Vienna, who assumed that this problem was on its way to being solved, are surprised to find themselves the focus for the anxieties of the age. They’re caught off guard in their colleges, law firms, and factories, midstep on their journeys toward assimilation. “Jews were baffled and shocked by this obsession,” Elon writes. “Should they react to the attacks or ignore them? Was it something they had done? Many sensitive young Jews were tormented by these questions. Rich Jews tended to blame poor Jews, and vice versa.”

The correct attitude among Jewish intellectuals, Herzl’s social circles, was to cringe at both rich and poor, affecting a very Viennese attitude of wry fatigue with the foibles of humanity. The writer works for the Neue Freie Presse, the New York Times of the empire, a newspaper of careful Jews who are celebrated for their brilliance, hampered by their social aspirations, and wrong, in retrospect, about everything. We don’t know that yet. Herzl’s plays are produced in Berlin and at the best theater in the city. Progress might not be smooth, but it is inevitable.

And yet society becomes increasingly preoccupied with the “bad manners” of the Jews. There are many people with bad manners, but the Jews stand out, “because of the obsessive interest in their lives and the general belief in the existence of a ‘problem,’ which even Jews paranoically began to share themselves.”

Books appear seeking to analyze the Jews’ warped character and physiognomy. This isn’t primitive hatred of Jews like in the days of the Church and the ghetto. This is science. As a young man Herzl reads one such book—Eugene Duhring’s The Jewish Question as a Racial, Ethical, and Cultural Question—and allows it briefly to penetrate his consciousness, mentioning his troubled emotions in his diary before relegating it to the back of his mind. One of the most toxic tracts would eventually be written by a Jew by the name of Otto Weininger. Like all Jews willing to attack other Jews, Weininger was borne upward on a strange, grateful tide of popularity, before taking his critique to its logical conclusion and killing himself. “When a number of frightened Jewish scholars publicly endorsed the new ‘scientific’ antisemitism and admitted the ‘biological’ inferiority of their race,” Elon writes, “other Jewish wits replied that ‘antisemitism did not really succeed until the Jews began to sponsor it.’”

Viennese politicians begin understanding how effective this hatred can be as a mobilizing tool. The dark word “they” comes into use—everyone knows who “they” are.

The most adept of this breed is Karl Lueger, who rides Jew-hatred into power but has Jewish friends. “I decide,” he famously declares, “who is a Jew.” It’s a type becoming familiar in our own time. Jews like Herzl believe that the genteel people in the palaces and grand townhouses of Vienna are in control of events, and that culture will thus prevail. But power is shifting to the gutter.

Herzl’s newspaper sends him to be the correspondent in Paris, the capital of European culture and the first country to emancipate its Jews. But here, too, there is that same buzz—dark stories of Jewish finance, of Jewish treachery and fakery. And here the journalist doesn’t do what one would expect, what his colleagues and friends and wife were all doing. He doesn’t invent a story about why none of this is about him.

He’s covering Paris in 1894 when a story about Jews, or rather one Jew, transfixes France. An artillery officer, Alfred Dreyfus, a member of the general staff, is accused of treason. It is in fact the Jews who are on trial. There are riots in the street. Dreyfus, who has been framed, is defended by the forces of liberalism and excoriated by the forces of reaction, including the army. France is tearing itself apart about what kind of country it wants to be, and this colossal battle is joined over the “Jewish problem,” just as such battles are currently being waged in America and elsewhere in the guise of a debate about “Israel.” Who is this Dreyfus, and the people he represents? What is he hiding? Is he one of us? Who is “us”?

With his notebook and press credentials, Herzl goes to a military barracks to cover the ceremony at which this question is answered. Soldiers line the courtyard. Dreyfus has his ranks torn off and his sword broken. Outside the mob howls, “Mort aux juifs!” Death to the Jews!

He reports back to his editors in Vienna, where Lueger is gaining support, and will eventually be mayor. Almost nothing will be left of the Jews of Vienna, or of Europe. Herzl’s own daughter will die in a concentration camp. Lueger’s rhetoric about the Jews will directly inspire a stunted Austrian who came to the metropolis with dreams of an art career, but who takes up a different career altogether. He was commemorated in one of the popular hashtags on Twitter this past month, #HitlerWasRight.

Hello, Vienna. Is it a comfort to know that we’ve been here before? Not really. Progress, when viewed from this angle, seems as fictional as the comedies of manners that Herzl wrote for the Burgtheater, and which no one remembers. Machines advance and the human soul does not. But this isn’t the whole story.

Herzl is inflamed by these events, which give him no rest. An idea begins to form. This idea is not to disappear (he’s tried!) or to plead for better treatment. He doesn’t try to “shift the narrative,” or swear loyalty to whatever political power seems ascendant, or modify the behavior of the Jews—the Jews, he understands, are the target of these poisonous stories, but the stories aren’t their fault. Freud is working just then a few doors down from Herzl’s house in Vienna, but even before psychoanalysis it was clear that an obsession is a mental malfunction in the obsessed party, not in the object of the obsession. A different solution is required.

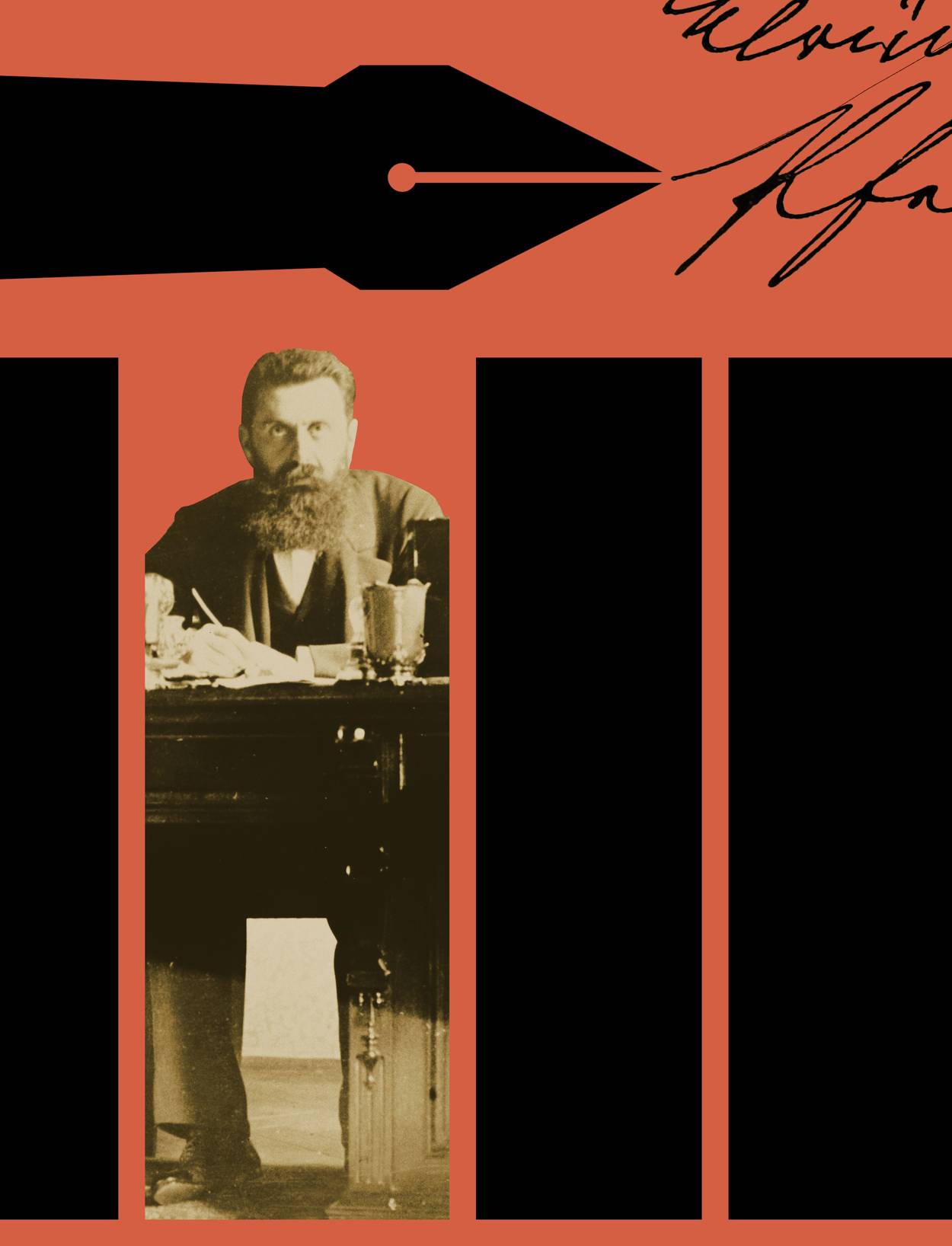

Observers in the Tuileries Gardens in the first days of June 1895 see Herzl pacing furiously. He’s gaunt. People think he’s mad, as many will in the coming years. He’s muttering, running through German sentences in his mind. His faith in Western progress was wrong. The way he thinks his new plan will play out is wrong. But his faith that he can bend reality for his people—this is astonishingly, incontrovertibly right, which is why I could pick up his biography 126 years later among stacks of Hebrew books on a street in Jerusalem.

Herzl leaves the garden and hurries back to his hotel room. He sits at the desk and picks up his pen.

With thanks to ‘Herzl,’ by Amos Elon (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975)

Matti Friedman is a Tablet columnist and the author, most recently, of Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai.