Thomas Ligotti’s Uncanny Horror and the Future of Holocaust Fiction

With Penguin Classics’ recent republication of ‘Songs of a Dead Dreamer’ and ‘Grimscribe,’ a new look at the worst-case scenarios of the universe

Until a couple of years ago, Thomas Ligotti’s name was barely a sinister whisper amidst the larger horror community, only known by true genre connoisseurs. He was the top-shelf stuff, his writing reserved for readers with palates supposedly developed enough to digest his works of unease and dread. That all changed with the New Weird’s creep into public consciousness—Jeff VanderMeer’s best-selling Southern Reach Trilogy, along with critical and financial darlings like The Leftovers and American Horror Story and Nic Pizzolatto’s True Detective, whose premiere season draws the most directly (some would say a little too directly) from Ligotti’s essays and fiction. Ligotti’s own popularity has risen sufficiently that Penguin Classics has recently republished some of his most acclaimed works, Songs of a Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe.

Ligotti would almost undoubtedly disdain the association of his work with any semblance of religiosity. This is, after all, the man who once remarked that Judeo-Christian adherents “trust the deity of the Old Testament, an incontinent dotard who soiled Himself and the universe with his corruption, a low-budget divinity passing itself off as the genuine article.” His simultaneously bleak yet darkly funny philosophy treatise, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (2010), renders all of human experience as an evolutionary aberration, a tragicomic cosmic joke resulting in mechanical organisms much too aware of their own consciousness to be of any benefit to themselves or the universe at large. While we can laugh at our own misfortune, and write about it, the objectively moral act is to collectively stop reproducing and die off altogether. “One cringes to hear scientists cooing over the universe or any part thereof like schoolgirls over-heated by their first crush,” Ligotti writes in Conspiracy, later adding with his own emphasis, “But it would be nice if just one of these gushing eggheads would step back and, as a concession to objectivity, speak the truth: THERE IS NOTHING INNATELY IMPRESSIVE ABOUT THE UNIVERSE OR ANYTHING IN IT.”

The bleakness of Ligotti’s work strikes an odd resonance in the context of post-Shoah Judaism. Although the religion’s emphasis on creating a kehila kedosha, a holy community, in the here and now may be seen as the opposite of Ligotti’s nihilism, faith itself can be seen as a type of “uncanny belief,” and I think that this notion is important to consider for modern Jews. The uncanny is first attributed to Sigmund Freud’s and Ernst Jentsch’s explorations of the idea in the early 20th century. In 1906, Jentsch defined the uncanny as an “intellectual uncertainty; so that [it] would always … be something one does not know one’s way about in.” Further extending this concept into literature, he writes that, in its most effective form, it will “leave uncertainty in the reader whether a particular figure in the story is a human being or an automaton and to do it in a way that his attention is not focused directly on his uncertainty.” As a Jew, I have faith in the holiness of community, in some sense of divine wonder, but I choose this faith knowing there is always the possibility of it being a sham. I may only possess “the story of my life, which has no more life in it than story,” as Ligotti describes in Songs of a Dead Dreamer’s “The Lost Art of Twilight.”

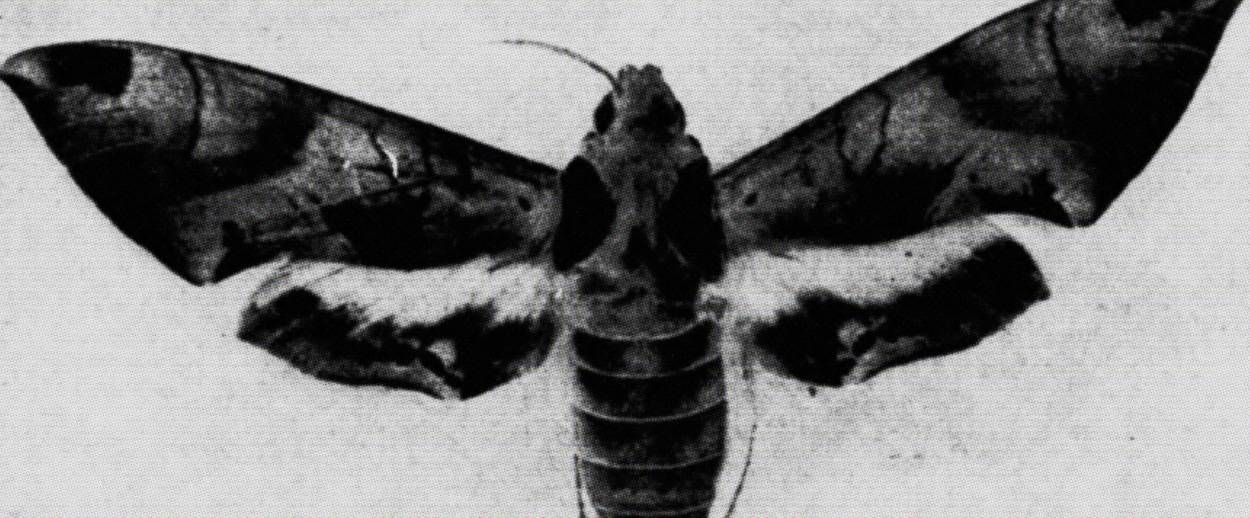

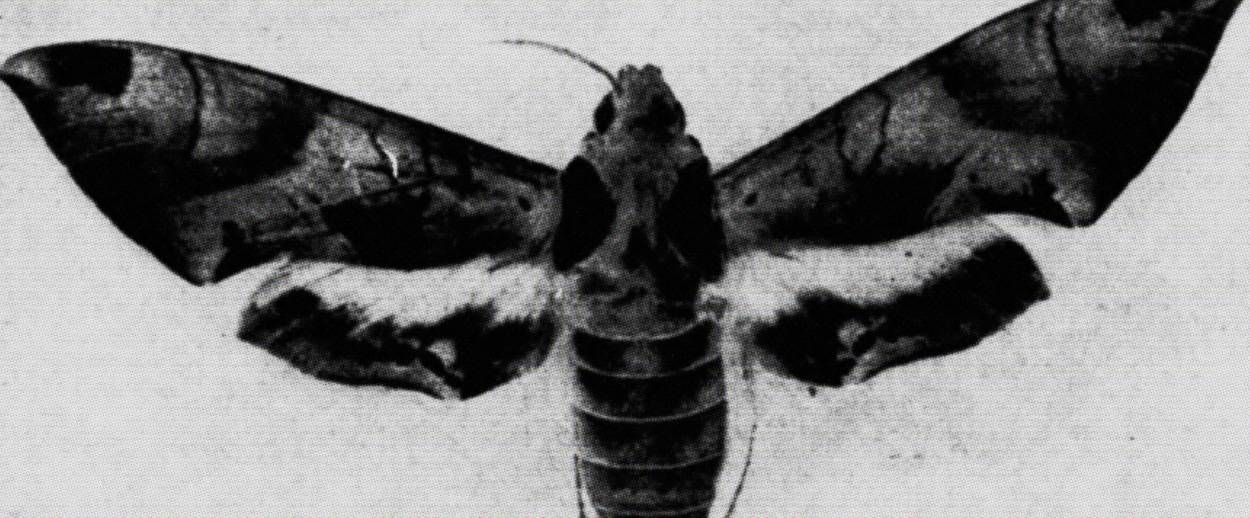

The bleakness of Thomas Ligotti’s work strikes an odd resonance in the context of post-Shoah Judaism.

The uncanny doubt that is part of the dialectic of Jewish faith has become all the more prevalent in the shadow of Hitler’s atrocities. If there ever were an antithesis to Sinai’s cloud of glory—an event that could shatter God’s covenant with Israel—then it would be found in the ashes of the Shoah. The death of God’s relationship with humanity, a popular 20th-century post-Holocaust theodicy, would be a “cultural fact,” as Richard Rubenstein writes in After Auschwitz (1966), and evidence “that the thread uniting God and man, heaven and earth, has been broken.” It doesn’t negate the existence of a deity; rather, it infers that the lines of communication are currently down between us and the divine. If this is our reality now, then cosmic, uncanny horror in the vein of Ligotti’s work provides some the best and most interesting alternatives for future generations of Jews to explore the emotions inevitably present in the realization of humanity’s helpless and potentially unending solitude.

“Dream of a Manikin,” one of the most effective tales in Ligotti’s collection, and arguably the most appropriate to this line of thinking, unfolds as a letter from one psychiatrist to another, possibly a paramour, whom we are led to conclude shares many of the author’s beliefs. The narrator occupies the role of resident “egghead,” as Ligotti earlier describes, recounting a patient seemingly referred to him by his correspondent. At least in regards to the author’s own personal philosophy, this is one of his blunter works, but that doesn’t detract from the pervasive, effective dread and unease occupying much of the story. “Dream of a Manikin” explores the notions of deluded self-consciousness and the fabrications of autonomy, primarily in how humans relate to one another. Ligotti’s dreamscapes echo his own belief that we are all self-deluded “manikins” traveling through life trying to maintain a blissful, unquestioning ignorance of our sad truth.

Holocaust literature is a genre in and of itself with its own insights, complexities, and shortcomings. As the last survivors of the Shoah leave us, depicting this tragedy becomes even more problematic—is it possible to tap into an honest portrayal of the horror at 80, 90 years out? A century or more? As a Jewish writer, I’m not sure I will ever be comfortable attempting fictionalized accounts of these very real monstrosities, but the theological quandaries still linger. Songs of a Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe are certainly not Ligotti’s attempt at exploring Shoah theodicies, but their masterful spook stories can be a blueprint for authors interested in subversive ways of tackling the notions of cosmic injustice and inhuman horror. If employed properly, uncanny horror can be the future of Holocaust literature for the generations feeling the pull toward investigating those uneasy feelings that something fatally wrong exists among us.

Maybe it is, as Ligotti says, the self-delusion of consciousness in a universe wholly devoid of anything divine, or maybe that fatal wrongness is simply the capacity for inhumanity residing in all of us. Ligotti’s pessimism can be a lot like scream therapy. These worlds and characters devoid of hope are the worst-case scenarios of the universe, and a possibility we should all face head-on.

A passage near the conclusion of “Dream of a Manikin” includes a surprisingly overt nod to Jewish theologian Martin Buber. Ligotti’s psychiatric narrator references the types of relations that can exist between individuals. Desperate to reassert his previously assured take on the universe and its inhabitants, the psychiatrist pleads to his recipient, this former flame, a relationship since severed: “Forget other selves,” writes the narrator. “Forget the third (fourth, nth) person view of life in which some god or demon has individuated itself into bits and pieces of all that is. Only first and second persons matter (I and thou). … So please be so kind as to acknowledge the reality of my existence.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Andrew Paul‘s work is recently featured in VQR, Oxford American, VICE, and The A.V. Club. He lives in New Orleans.