Three-Part Harmony

A new book shows how Nazism and the Ku Klux Klan prompted the American establishment to look beyond longstanding divisions and see Catholics, Protestants, and Jews as kin

After he was elected president in 1952, Dwight Eisenhower made a famous statement of belief that nicely summarized the mid-century American creed: “Our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” There is something absurd about the way the second part of the sentence casually annuls the first: If you don’t care what people believe about God, how “deeply felt” can your own beliefs really be? What Eisenhower really seems to be saying is that religious people make good citizens—more bluntly still, that fear of God is needed to keep people in line.

This principle may or may not be true, but it has nothing to say about the truth or falsehood of any particular religion. Presumably, if Americans started sincerely worshipping Zeus or L. Ron Hubbard, they would get all the same civic benefits as if they were pious Jews, Catholics, or Protestants. The temptation to make a religion of religion, to recommend that other people believe doctrines one does not believe oneself, is a standing temptation for ideologues, especially on the right.

Yet the generosity of Eisenhower’s statement is even more striking than its awkwardness. When you consider how much blood has been spilled over questions of theology, there is something quite wonderful about the way Americans are so eager to give every religion equal credit for good intentions—or even to believe that good intentions are more important than theological correctness. And what is most amazing of all is the way Jews are automatically included in this consensus—in what Eisenhower went on to call “the Judeo-Christian concept.” The very term “Judeo-Christian,” which is now a cliché in American political discourse, represents a healing of a 2,000-year-old breach, an off-hand repudiation of the whole bloody history of Christian anti-Judaism.

When and how did America start to think of itself as a Judeo-Christian country, rather than what it historically has been, a Protestant one? That is the question Kevin M. Schultz asks in Tri-Faith America: How Catholics and Jews Held Postwar America to Its Protestant Promise (Oxford), and he gives a very concrete answer. The change came about in the 1930s and 1940s, thanks primarily to the concerted effort of the National Conference of Christians and Jews, a lobbying and educational group founded in 1927. In fact, the first half of Tri-Faith America reads like a history of the NCCJ, as Schultz draws on archival material to show how the group developed its programs and understood its mission.

That mission was even clearer in the group’s original, unwieldy name, National Conference of Jews and Christians (Catholic and Protestant). For if one of its goals was to bridge the divide between Jews and Christians, the other was to stimulate good will between Protestant and Catholics—groups whose antagonism had been a far more important feature of American history. Indeed, from any reasonable point of view, Catholics posed a much greater challenge to the hegemony of American Protestants than Jews ever could: At mid-century, the population was estimated to be two-thirds Protestant, one-quarter Catholic, and 3 percent Jewish. To many Protestants, moreover, Catholics were inherently unsuited to democracy, because of their obedience to the Church and their communal clannishness. Not until the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 would this kind of hostility be wholly put to rest.

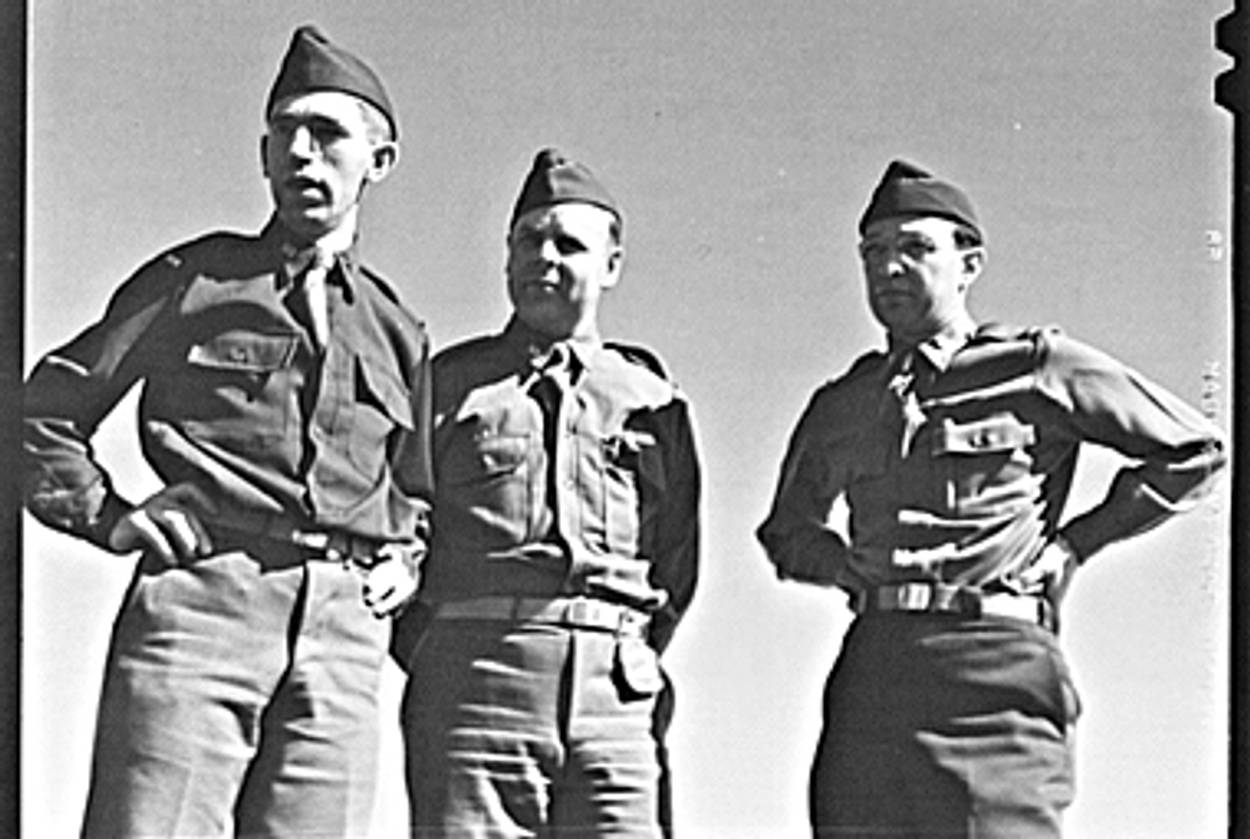

It is greatly to the credit of America’s mainline Protestant leaders, then, that in the 20th century they put the weight of the Establishment behind the “tri-faith” vision and against the forces of bigotry. The NCCJ had its origins as a reaction to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, with its anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic hatreds, and took new urgency from the rise of Nazism in 1930s Europe. Its most popular programs were the so-called Tolerance Trios, in which a priest, minister, and rabbi would tour the country conducting public discussions. The NCCJ’s head described these tours as a benevolent American “ ‘storm-trooping’ … in sharp contrast to Nazi precept and procedure.”

Anodyne as the Tolerance Trios sound, they did have to overcome some initial resistance, notably from the Catholic Church. Some bishops refused to allow priests to appear in a setting that suggested parity with ministers and rabbis. Yet the clergy who took part in the Trios went out of their way to minimize doctrinal differences. At one conference in the early 1930s, a priest told a Methodist questioner, “I would hope that you should become a Catholic. But as long as your reason and conscience truly lead you to do otherwise, you have as good a chance to get to heaven as any Catholic.” As Schultz notes, this was “a bit theologically soft regarding the Catholic position,” but for that very reason it was a good example of how the rhetoric of tolerance helped to produce the reality. The official NCCJ formula, “the brotherhood of men under the fatherhood of God,” nicely elided dogmatic differences.

World War II, Schultz shows, was when Tri-Faith America became official government policy. Privately, Franklin Roosevelt could be cutting about Jews and Catholics, once announcing that the United States was “a Protestant country, and the Catholics and Jews are here under sufferance.” But during the war, the political appeal of “brotherhood” was too obvious to ignore. Not only did it serve to tamp down ethnic and religious prejudices that could hinder the American war effort, but it provided a perfect foil to Nazi racism. “We are at war with a people claiming to be a ‘lordly race,’ ” said Henry Sloane Coffin, a leading American Protestant minister. “We must hold fast to our national unity by insisting that all men have one heavenly father who wills His Children to honor and serve one another as brethren.”

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, then, the NCCJ was given free access to the American military. Tolerance Trios visited camps and bases; soldiers were issued pamphlets with titles like “A Faith for Young Men in the Armed Forces” and “Why We Are at War.” Perhaps the most concise and moving statement of tri-faith unity was the “prayer card” issued to every soldier, containing Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish prayers to be read to a dying man. The kitschiest example, on the other hand, may have been the football game at Ft. Benning described by Schultz in which the marching band formed into a Star of David and played a rousing version of “Ein Keloheinu,” before reforming as a cross and playing “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

The NCCJ representative at that game noted happily that “the massed thousands cheered wildly and warm-heartedly this gesture of good-will.” But then, he wasn’t exactly a neutral party. Schultz’s institutional focus on the NCCJ means that he has little to say about how its propaganda was actually received by citizens and soldiers and what kind of concrete impact it had on bigotry. (Tom Lehrer, the musical satirist, offered an astringent view in his song “National Brotherhood Week”: “It’s fun to eulogize/ The people you despise/ As long as you don’t let ’em in your school.”)

Schultz’s treatment of the intellectual and theological dimensions of the subject is also fairly summary. Inevitably, Schultz mentions Will Herberg, whose 1955 book Protestant-Catholic-Jew “affirmed the arrival of Tri-Faith-America,” but he has less to say about Herberg’s critique of this concept as “religiousness without religion … a way of sociability or ‘belonging’ rather than a way of reorienting life to God.”

His focus in the second half of the book is, rather, legal and sociological. If World War II enshrined “the brotherhood of man under the fatherhood of God” as an American principle, the 1950s and 1960s saw Americans wrestle with its limits and contradictions. For one thing, Schultz emphasizes, the divisions among Protestant, Catholic, and Jew were far easier to talk about than the gulf between black and white. The NCCJ faced periodic pressure to broaden its mandate to include civil rights issues; but while many of its members were sympathetic to the cause, the organization itself remained highly cautious.

Still, Schultz argues in his last chapter, “From Creed to Color,” that the tri-faith emphasis on “brotherhood” and “the Judeo-Christian heritage” helped to prepare the ground for the civil rights movement, by giving it “a language to tap into.” In his “I Have a Dream” speech, Schultz notes, Martin Luther King Jr. invoked the tri-faith formula when he referred to the day “when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands.”

Yet other postwar developments helped to expose the fault lines in the tri-faith alliance—in particular, the conflicting agendas of Jews and Catholics. While both of these groups wanted to fight discrimination from the Protestant Establishment, they had different visions of what America should be. Jews, as a small and historically persecuted minority, understood America as a secular country, where Church and State were totally separate. Thus, Jewish plantiffs and lawyers helped to litigate the landmark Supreme Court cases that barred school prayer in the early 1960s, and Jewish organizations strongly objected to plans to include a question about religion on the 1960 census. Catholics, Schultz shows, came down on the other side of both issues. As a large and well-established group, they welcomed a recognition of their numbers and wanted a role for religion in public life.

Such disagreements, heightened by Jews’ memories of Catholic persecution, tested but did not break the tri-faith consensus. Today, as Schultz observes, the major divisions in American life cut across religious boundaries. On issues like abortion, homosexuality, and school prayer, conservative Protestants, Catholics, and Jews have much more in common with one another than with their liberal coreligionists.

But the real test for the tri-faith model, which Schultz barely addresses in his book, will be the assimilation of new religious groups into the “Judeo-Christian” model—above all, Muslims. From Ground Zero to Orange County, the last year witnessed a series of revolting demonstrations of anti-Muslim prejudice in the United States, reminiscent of the kind of bigotry that Jews and Catholics once faced. Tri-Faith America shows that our religious diversity has been a process of mutual accommodation: As “foreign” religions become less dogmatic and distinctive, Americans stop seeing them as alien or threatening. With luck, the same benevolent process will allow us, a few generations from now, to talk blithely of America’s Judeo-Christian-Islamic heritage.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.