On Tokens and Tokenism

From George Washington to Jill Biden, Black literature has long been plagued by ignorant white patrons, who arbitrarily anoint a few writers as symbols of the Black experience

Tokens are the bane of Black literature, and for that matter, Latinx, Native American, and Asian American literature. They are often selected arbitrarily as symbols by those who know little about Black literary traditions or literature in general, and their work overshadows the production of writers who might write as well or better.

From George Washington, who anointed the poet Phillis Wheatley back in the day, to Jill Biden, who gave Amanda Gorman the nod earlier this year, a powerful white patron can offer a Black writer huge sales and exposure. In return, these writers become the go-to sources about the Black experience for readers as well as academics who are spared the trouble of viewing Black writing as a tradition that extends at least to the 1700s. This includes Black writer-slaves who wrote in Arabic. Instead, we are limited to renaissances, each generation canceling the previous ones.

Both John A. Williams and John Oliver Killens, who wrote as well as any of the tokens, agreed that once a powerful white literary trend-maker or institution selects a token, segments of the Black cognoscenti line up to ratify the choice no matter their politics. Before the decline of the Black newspapers, those writers who were neglected by the outsiders, who control the patronage networks, could get some space. Langston Hughes, John A. Williams, and Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote for newspapers. Dunbar’s newspaper, The Dayton Tattler, was supported by his classmate Orville Wright. Black writers had influence over which of the younger writers would receive support.

Then came the ascendancy of critics who are housed in universities and paid by foundations. These critics decide which writers will receive grants that might provide them the time to complete creative projects. Critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. controls the patronage of at least three foundations. He often provides grants to his Harvard colleagues instead of awarding them to creative writers. Contrast this with the generosity that Richard Wright extended to a struggling James Baldwin. In 1948, Wright used his influence to provide Baldwin with a Eugene Saxton Memorial Trust fellowship from the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

For my part, after the publication of my novel Reckless Eyeballing I was left as literary roadkill because I took aim at some of the dizziest ideas of bourgeois feminists, among them women who regarded Valerie Solanas as a hero, viewed male ejaculation as “an act of war,” or argued that Emmett Till, who allegedly whistled at a Southern white woman—who confessed on her deathbed that she lied—was just as guilty as his murderers. Luckily, I received a cash award from the great poet Gwendolyn Brooks that helped to sustain me, financially.

Who are some of the writers that have been neglected by these guardians of patronage more likely to extend grants to fellow professors than to struggling artists?

Louise Merriweather could use a grant. Ninety-five-year-old Merriweather had to raise $36,000 through GoFundMe for round-the-clock care after she contracted COVID-19. Her 1970 Harlem novel, Daddy Was a Number Runner, was as good as any Harlem novel including Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain. But those who curated Black culture at the time might have found some of her characterizations uncomfortable. For example, her novel reports that Harlem girls had to submit to fondling by lecherous shop owners in exchange for food (a practice that still goes on in my Oakland inner-city neighborhood, except the predators might be Muslim immigrants who have a traditional family in the suburbs and a “baby momma” in the ghetto.) Merriweather might have also been obscured because of her role in halting the film production of William Styron’s 1967 Confessions of Nat Turner, in which the Black hero was subjected to trendy pop psychoanalysis by the author—to which she took objection.

Mrs. Merriweather is a writer who doesn’t hold back. She could have used the backing of Karen Durbin, the white feminist former editor at The Village Voice who takes credit for Gates’ rise as a public intellectual. A Black writer who worked there told me that the white women who had editorial positions were always encouraging her to attack Black men.

Durbin and her ilk are part of a tradition of token creators that reaches back to George Washington. So flattered was Washington by Phillis Wheatley’s 1775 tribute to him that he offered to publish her poem, a panegyric to his achievements, but decided that it would be vain and instead sought to have the poem published by another publisher. Washington sold a slave for rum, raffled off slave children to pay his debts, and was a dedicated fugitive slave hunter. Maybe Ms. Wheatley was not aware of Washington’s treatment of slaves who lived in miserable conditions, according to a visitor to Mount Vernon as he worked to have her poem published. Regardless, Phillis Wheatley became the most famous Black person of her time, and the first Black American literary token. I’m sure that some other poets and storytellers of her time were just as good.

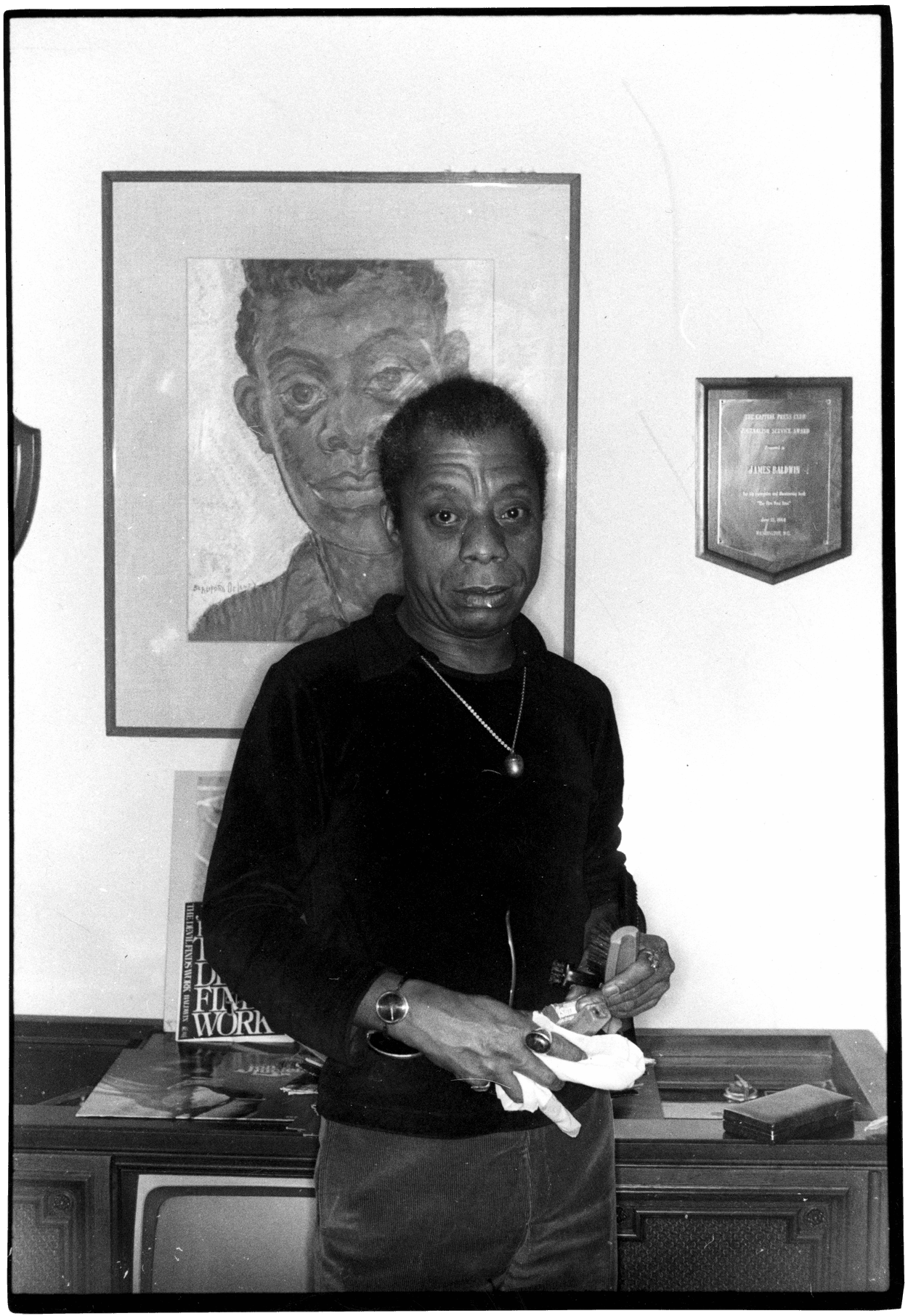

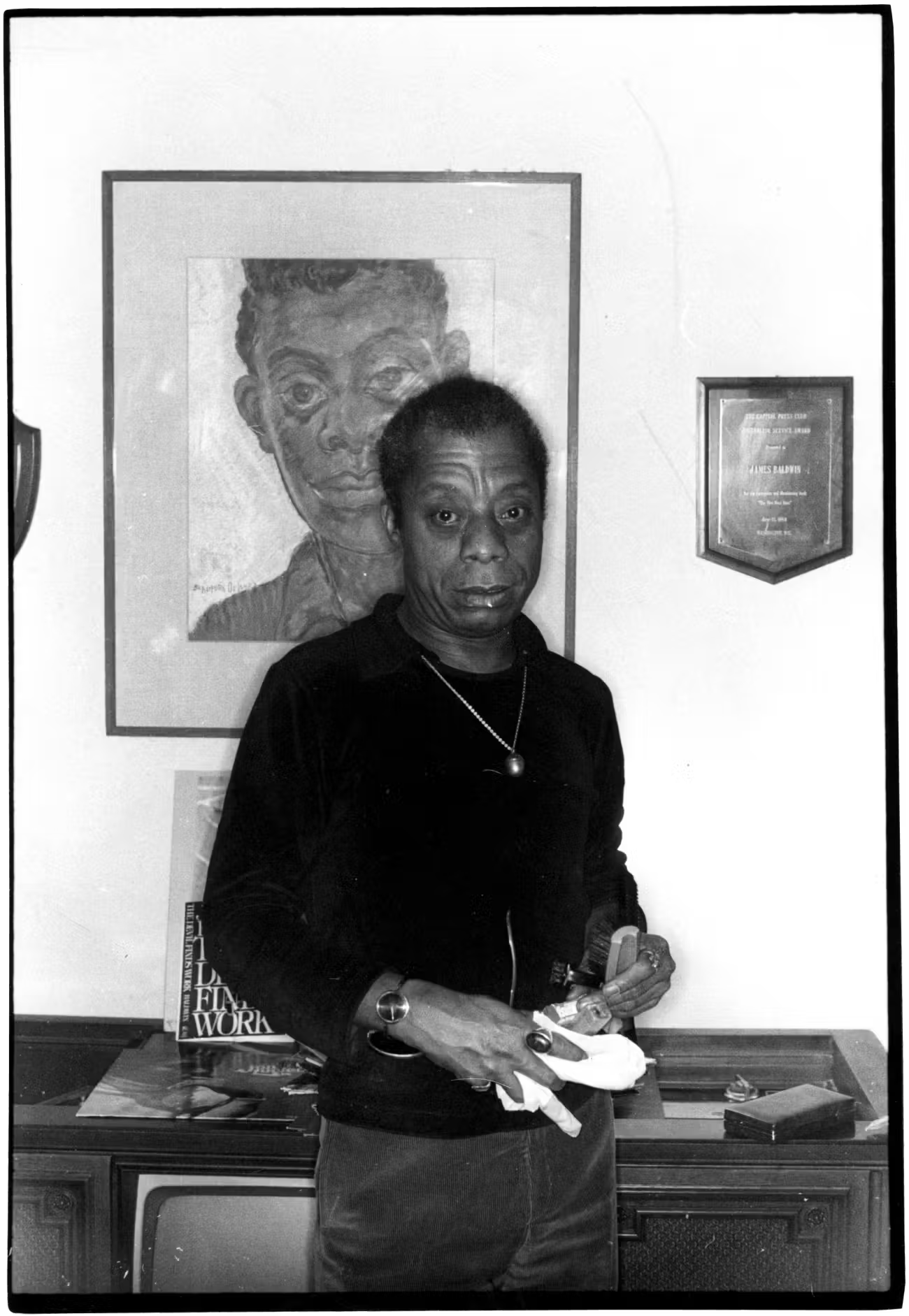

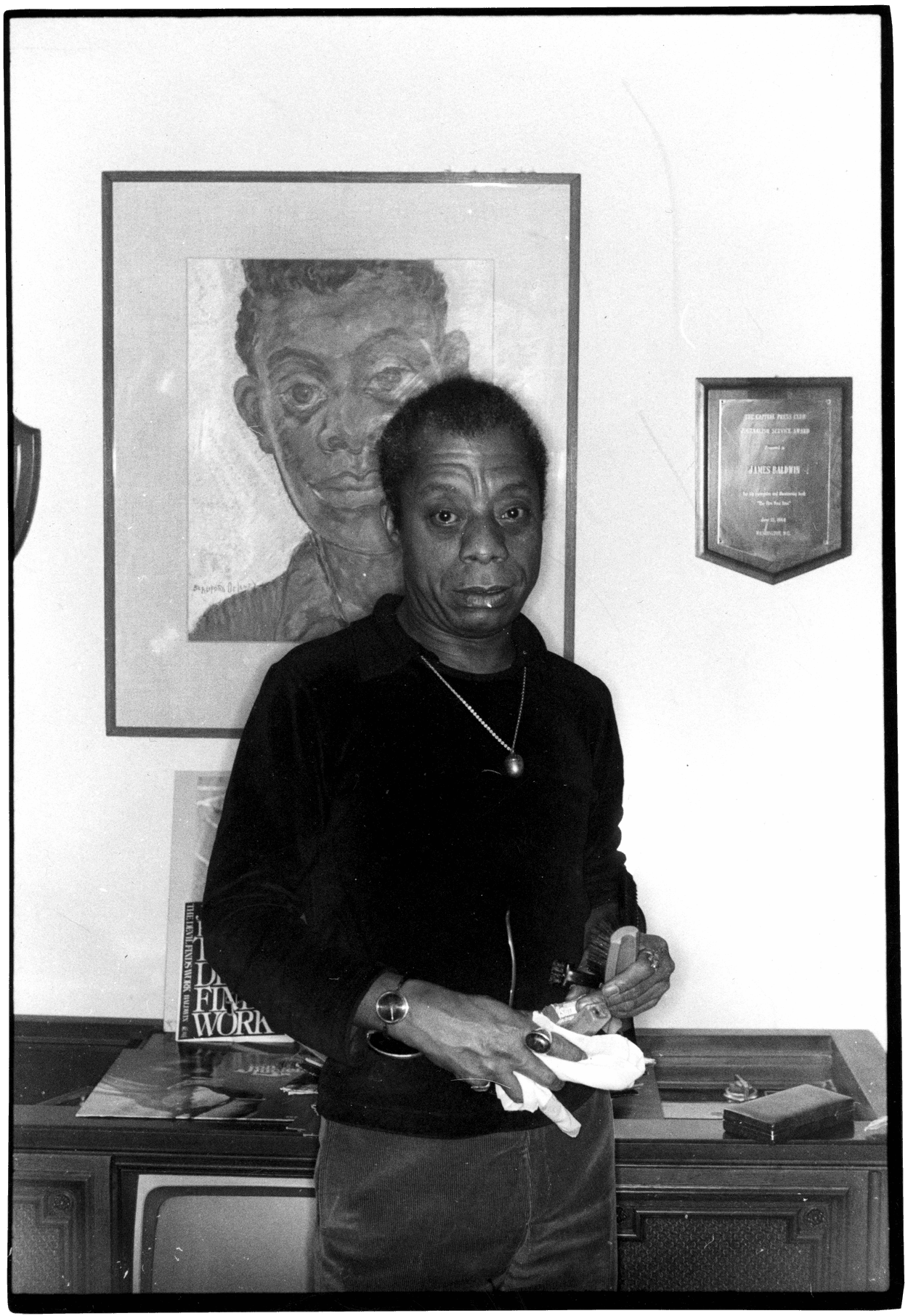

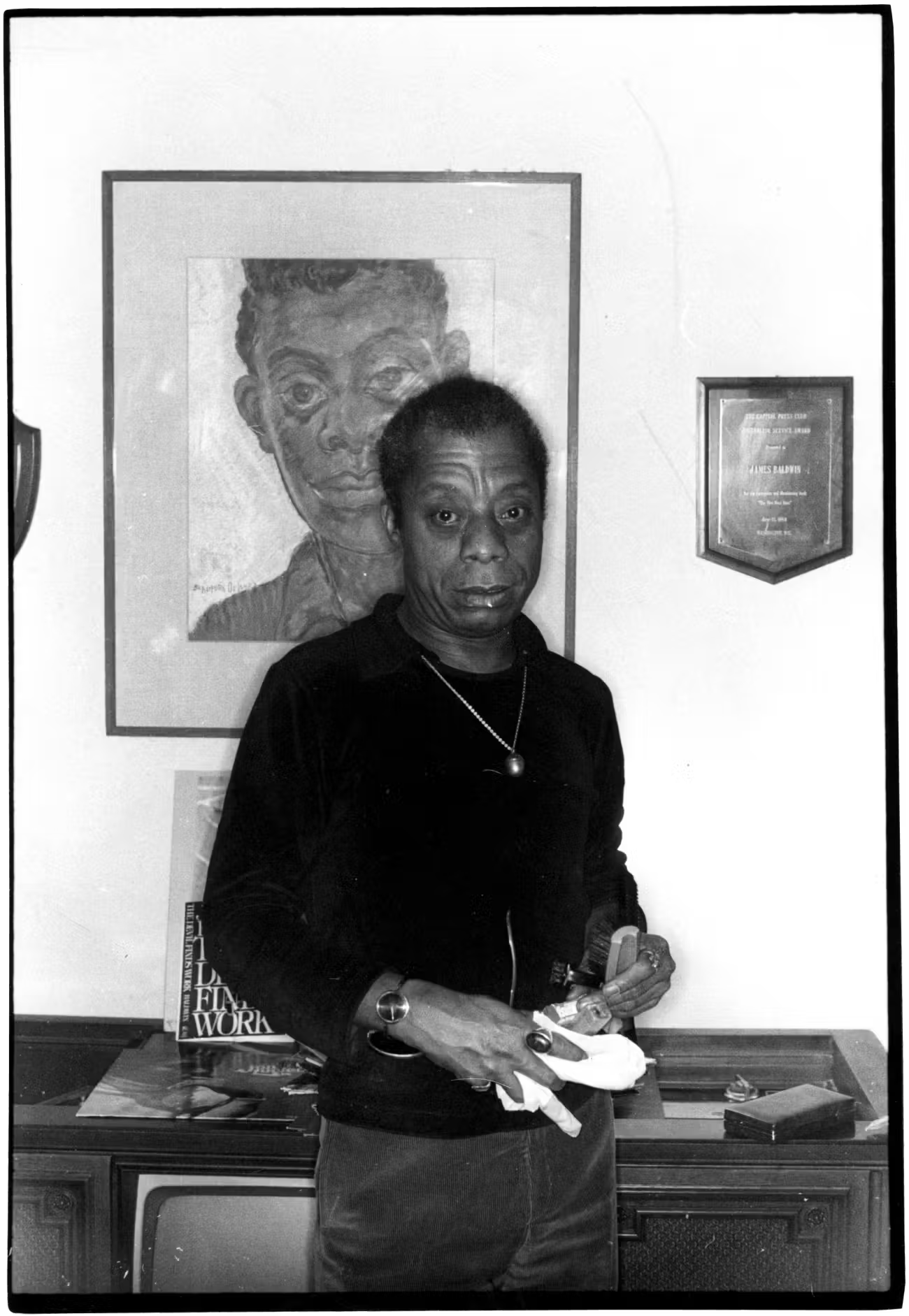

I often get into arguments with liberals, Black and white, when I direct them to writers who write as well as the tokens. They are invested in the belief that because they’ve read Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (1963) they have Black literature covered. Very few of the tokens had as much support from powerful sources as did Baldwin, whose champions were the members of the New York literary elite—literary modernists like William Phillips of The Partisan Review, and Philip Rahv, who was responsible for Baldwin’s receiving a contract for Giovanni’s Room. One of the reasons that Phillips published Baldwin’s Everybody’s Protest Novel, a fierce critique of notable Black protest novels like Richard Wright’s Native Son (albeit with an ironic title, since protest also runs through Baldwin’s novels), was because Phillips regarded Wright as lacking patriotism.

Phillips was the chairman of a literary organization of which I was a member. Without having read their work, Phillips deemed two of my nominations to the board to be unqualified. They were the late Toni Cade Bambara and Leslie Marmon Silko, both of whom are now part of the canon. Silko was just elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

If the champions of Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, which promised to redeem white liberals instead of harming them, had read works other than The Fire Next Time, they would have discovered that by the time he wrote Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, a roman à clef, in 1968, Baldwin had given up on redeeming liberals. In this novel, he gave his sponsors on the white left the finger in such a scathing manner that Mario Puzo was hired to do a hatchet job on the book in The New York Times Book Review on behalf of The Family, the New York literary establishment, which has been laying tokens on Black writers for over 100 years.

After that rebuke of those who brought him fame, according to Truman Capote, who was interviewed by Cecil Brown, and published in Quilt magazine by the late Al Young and me, the New York establishment then treated him like “shit.” Baldwin was replaced by Eldridge Cleaver, who, according to Ralph Ellison, another token with powerful white sponsors, was also “publicity sustained.” The same issue of Quilt carries a story by Mona Simpson, then a student. She is now the publisher of The Paris Review.

Presently, there are more Baldwin imitators than Elvis impersonators. Every token and his brother are writing letters to their nephews. But Baldwin was shrewd. He was writing to the “Chorus of Innocents” who was looking over his shoulder. His was a variation of the old indulgences game that was promoted by the Catholic church in the late Middle Ages. Buy my product and you’ll only have to spend one year in purgatory instead of two. Of course, the Baldwin cult neglects to mention the Black writers that he stepped on during his ascendancy.

The newest star creator is Jill Biden, who heard Amanda Gorman read poetry and chose her as an inaugural poet. Predictably, the Black cultural elite swooned all over this choice, and powerful whites with media power who know little about Black literature chimed in. A chorus of academics and intellectuals, who display their militancy at every opportunity, endorsed Ms. Gorman’s trite, platitudinous high school patriotism, the poetic equivalent of the song “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” Chinese American poet Genny Lim was called a “racist” for pointing out the flaws in the poem.

Ms. Gorman’s admirers seemed to be more impressed by her presence than by the poem. Such is the adoption of Black Lives Matter by upscale commercial interests that author and critic Hilton Als and I speculated that were she around nowadays, Fannie Lou Hamer might appear on the cover of Vogue wearing a bikini. Though the poem was earnest and well-intentioned, if the first lady wanted a Black woman poet, why not veterans like Nikki Giovanni, Mae Jackson, Sonia Sanchez—women who are household names among Blacks? Moreover, why would the first lady snub three-term U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo, a Native American, one of perhaps 25 American poets who will be recognized a hundred years from now?

Of course, the first lady wasn’t obligated to choose Harjo. But the slight, called “inadvertent” by Showbiz, was noticed by many writers. The other problem with Gorman was her praise of Hamilton, the musical hit based upon the lie that Alexander Hamilton was “an ardent abolitionist.” Asked about my play, The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda, which challenges that view of Hamilton as an abolitionist, during an interview by Doreen St. Felix for a Vogue article titled “The Rise and Rise of Amanda Gorman,” Gorman dismissed me as “intense.” I find it bizarre that Ms. Gorman and the former first lady, Michelle Obama, would praise a play that glorifies Hamilton. Alexander sold at least one Black woman and her child. What kind of history are they teaching at Harvard?

Jesse Serfilippi’s article, “As Odious and Immoral a Thing: Alexander Hamilton’s Hidden History as Enslaver,” scored a literary coup de grace on those who would promote the fiction that Hamilton was an abolitionist. Those who were among the first to question Hamilton’s credentials as an abolitionist were historians Michelle DuRoss, Lyra Monteiro, and Nancy Isenberg. I merely staged these arguments. Would Ms. Gorman call these women scholars “intense”? Like Phillis Wheatley, Ms. Gorman gave a nod to a slave trader whose solution to the “Indian” problem was extermination. Of course, her presence and performance gave Time magazine an excuse to lay another renaissance on us when they had promised that their last renaissance, framed by Henry Louis Gates Jr., was the greatest of them all (see: Time, Oct. 10, 1994). By contrast, I have been referred to as a “member of a previous generation,” like someone who has been buried alive. I’m still working in order to keep up with my steadily increasing long-term care premiums. To others, I am very much alive! An old coot up to mischief! The City Journal, an organ of the Manhattan Institute, which was founded by Reagan’s CIA Director William Casey, referred to me as an “old-timer” who is part of a “cancel culture mob.”

My response to them is that if they hadn’t taken tobacco money, some of their subscribers might have survived as long as I have.

There is such a turnover among the token crowd that it’s hard to keep up. But by my estimation, Ta-Nehisi Coates is the latest of the prominent tokens. Coates is a fine writer who was given to us by The Atlantic. Indeed, so powerful is The Atlantic, which is the second-oldest literary magazine in the United States, that its sponsorship of Coates placed him in a position where he could question President Barack Obama and weigh in on a presidential primary. He came to fame with his essay about reparations, the details of which are yet to be presented by the author. When asked “where do we go from here?” on reparations, he said he didn’t know and that he was just a novelist. Ta-Nehisi has my sympathies, though, for having to work under Jeffrey Goldberg, who apparently believes that Blacks and women don’t have the necessities to write a 15,000-word essay.

While the establishment tolerates a handful of token writers, Black critics are still confined to the literary Negro leagues. Some white critics who cover Black literature view it as an orphan searching for a master, like a critic who wrote that the late Black poet Wanda Coleman was indebted to Walt Whitman. I knew the late Los Angeles poet, Wanda Coleman, and published her. The only thing that the two have in common is that they both wrote in English.

Now, “people of color” are the new literary patrollers, and border guards for Black literature. Two books by Richard Wright were assigned to critics of Indian ancestry, one of whom accused Wright of promoting stereotypes. Wright’s daughter, Julia Wright, answered Pankaj Mishra in my magazine, Konch. As Indian novelist C.J. Singh has noted, the new literary patrollers of Black literature, who have been installed at The New York Times Book Review (traditionally the leading incubator of tokenism), have been trained by the British. I figure that they’ve been recruited by American Anglophiles to challenge the American vernacular, which has always been rowdy, subversive, and prone to uncontrollable outbursts like Rap. The late Dan Cassidy in his “How the Irish Invented Slang” writes about how this ethnic group contributed to the linguistic melee, and how we can’t overlook the great Grace Paley who wrote English with a Yiddish syntax.

Fortunately, organizers like Brenda Greene and Kim McMillon, both Ph.D.s, establish conferences whose purpose is to sustain a Black literary tradition. They have provided Black literary critics a place where they can do their stuff. The theme of the March 27, 2021, National Black Writers Conference Biennial Symposium, organized by Dr. Greene, was “They Cried I Am: The Life and Work of Paule Marshall and John A. Williams, Unsung Black Literary Voices.”

Why were Paule Marshall and John A. Williams “unsung?” Marshall’s 1984 novel, The Timeless Place, the Chosen People, is as good as any writing published by any writer who has received attention. The same is true of John A. Williams, who left behind three great books, The Man Who Cried I Am, Click Song, and Clifford’s Blues, about a Black musician who survives in a Nazi concentration camp by entertaining the personnel, who are lovers of Jazz at night, but murderers during the day.

Black members of the John A. Williams generation who served in World War II made the literary establishment uncomfortable because they challenged an army whose purpose was to end racism in Europe by writing about the racist treatment that they received in the army, where white Southern officers were assigned to manage all-Black divisions with predictable and disastrous results. Clifford’s Blues was initially rejected because publishers dismissed the notion that Blacks were placed in concentration camps. Luckily, Williams lived to see the book finally published.

John O. Killens wasn’t as fortunate. His novel The Minister Primarily is being published posthumously by Amistad, a company founded by another Black veteran, Charles Harris. I have written the introduction.

One of the finest authors of the last hundred years was William Demby. He chose to live in Rome where he collaborated with Italian filmmakers Rossellini, Fellini, Visconti, and Antonioni. Also a veteran, he couldn’t find a publisher for his final novel, “King Comus.” I published the novel in 2017. I also published Paule Marshall. If she’d obeyed the market and produced a Black bogeyman book of poems in which saintly women are besieged by one-dimensional brutes, the genre that another neglected novelist, Elizabeth Nunez, calls “girlfriend books” and which signals the Oprah-ization of Black literature, she wouldn’t have been “unsung.”

Those who challenge the system of tokenism promoted by those who know little about Black literature are predictably accused of envy (“You’re mad because they didn’t choose you”). I’ve received plenty of awards and honors in the United States and abroad. When I was groomed to be a token, I denounced it. So should the current tokens. By doing so, they will allow Black literature to breathe.

Instead of succumbing to the temptations of tokenism, I founded two literary organizations, PEN Oakland, called by The New York Times, “the blue-collar PEN” and the Before Columbus Foundation, which sponsors the American Book Awards. The board of directors of the Before Columbus Foundation includes the current and former U.S. poet laureates, a recipient of the Booker Prize, a MacArthur Fellow, two noted Italian American scholars, an Irish American detective novelist who is an Edgar finalist, an award-winning Alaskan Native American poet, and two award-winning Chinese American authors. Our president is a Pakistani American and our executive director is the son of immigrants from Latvia. Our chair is of mixed heritage. One of our early directors was the late Jewish American poet, David Meltzer, who was a star of the beat generation. Our late Chicano director, Rudolfo Anaya, received a presidential medal for literature. Such is our reputation as a writers’ organization that Don DeLillo, Edwidge Danticat, Gloria Naylor, and members of the younger generation like Jericho Brown have attended our awards ceremonies at their own expense. John A. Williams, Paule Marshall, and Louise Merriwether have received awards from us. The Before Columbus Foundation is entering its 42nd year of recognizing the talents who go unrecognized by the token-makers. But at the same time, we haven’t shunned well-established writers.

When asked by a Times reporter in 1980 why I founded the Before Columbus Foundation after receiving a prestigious award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters and was nominated for two National Book Awards in the same year, I said that there are others who are worthy. Since editing my first anthology in 1969 and having read thousands of manuscripts by Americans from all backgrounds, I have a different view of American writing than the token-makers. I remember an elderly white woman in Kentucky who had a 700-page novel. She got to write during the time when her ailing mother was asleep. I saw whole families attend Latinx literary festivals in Houston. I’ve attended poetry readings in Albuquerque where not a word of English was spoken. At the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, poets might read in Spanglish. Tlingit women write short stories in Sitka, Alaska. They are armed in case they run into a bear. At the ending of classes I conducted there, they presented me with a raven totem.

The West has a vibrant literary scene from Seattle to El Paso, which has been neglected by book reviews based in the Northeast. Haki Madhubuti’s Third World Press is located in Chicago. The late Toni Cade Bambara ran workshops in Atlanta. Kalamu Salaam anthologized 100 poets in New Orleans. Student writers create work that is as good as those printed in prestigious anthologies.

I placed my students and canonized writers in the same volume in my anthology “From Totems to Hip Hop.” Professors attending a conference couldn’t tell the difference. The token-makers claim that American talent is rare, and by doing so they are depriving American readers of a rich reading experience. Based upon my experience, American talent is not rare. It’s common.

This story was updated on September 15, 2021.

Ishmael Reed is a Distinguished Professor at California College of the Arts. He runs Konch magazine.