Tom Bird Bears Witness to Two Wars and the Holocaust

A Vietnam veteran wanted to bring to the theater a story about his father, a veteran of World War II. It meant facing the horrors of war with brutal honesty and love.

On the last Monday in April, the traditional month for Holocaust commemoration, actor and playwright Tom Bird seated himself at a bare table in a rehearsal studio a few blocks west of Manhattan’s theater district. He laid a 39-page script in front of him, a first-person narrative of two wars and one genocide with the rather prosaic title Bearing Witness.

Over the next 75 minutes, it became clear there was nothing at all ordinary in this text and performance. Bird had, in fact, created a wholly unique and arresting meditation on World War II, the Vietnam War, and the Shoah, with their valor and tragedy lashed together by a father-and-son story.

Bearing Witness also stands as a kind of summary of Bird’s life and career. At the age of 69, he has been defined by war and theater. He is a veteran and the son of a veteran. Theater rescued him from the embittered and self-destructive aftermath of the military duty in Vietnam, and, in turn, the art that Bird made with the Vietnam Veterans Ensemble Theater Company helped reconcile a divided America to the men who fought a failed and divisive war.

Nothing in Bird’s professional résumé, though, prepared him to produce a work of Holocaust literature. As a Roman Catholic, he was removed from the irreducibly Jewish nature of the Nazi mass murder. Yet a primal, filial motivation wound up leading him there—literally to the Mauthausen concentration camp, where his father had tended to survivors as an Army medic.

“To tell you the truth, I never looked at the story from the outside in,” Bird explained in a recent interview. “I was always telling it from the perspective of my relationship with my father. I loved my father, and I wanted to tell a story about him, and the best way to do that was to tell a story about us. The difference between our two wars was the most dramatic period of our life together. And concurrently, there was always Mauthausen. Even in my most troubled times after Vietnam, I always had a deep admiration for my father and who he was and what he’d done.”

The staged reading in April was intended to stir interest in the work among commercial producers. So is an invitation-only show in Los Angeles on June 20—appropriately enough, the day after Father’s Day. Already Bird is scheduled to perform Bearing Witness in September at the World Peace Initiative Film Festival in Orlando, Florida, and at Mauthausen in May 2017, marking the anniversary of the camp’s liberation.

In some respects, the theater piece had its genesis when Bird was 6 years old, the son of a Long Island doctor named Sam Bird. The elder Bird had enlisted a month after Pearl Harbor and went through the D-Day invasion and the Battle of the Bulge before entering Mauthausen the day after its liberation on May 5, 1945. The Austrian camp, used for slave laborers to mine nearby granite, had nearly 198,000 prisoners during its seven years of operation. Some 95,000 died, 14,000 of them Jews, and the crematoria were running until a week before American forces arrived. (These statistics are from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.) After being discharged, Sam Bird rarely spoke about his service. Early in Bearing Witness, Tom Bird recalls rummaging through his father’s duffel bags of Army memorabilia in the attic:

In the middle drawer, under sheets and mothballs, I found a big pistol, a jewelry box with a Bronze Star with a little “v” on it, a black-and-white patch of a skull’s head, and an envelope. In it was an antique-looking black-and-white picture of a pile of naked, bleached white, skeleton-looking bodies, stacked up against a building. I’d never seen anything like it. It was hard to imagine they were real people. My young soul was shocked and I’ve never forgotten them. I was caught that day and my plea, “Who are they, Dad?” was cut off, “You’re too young!”

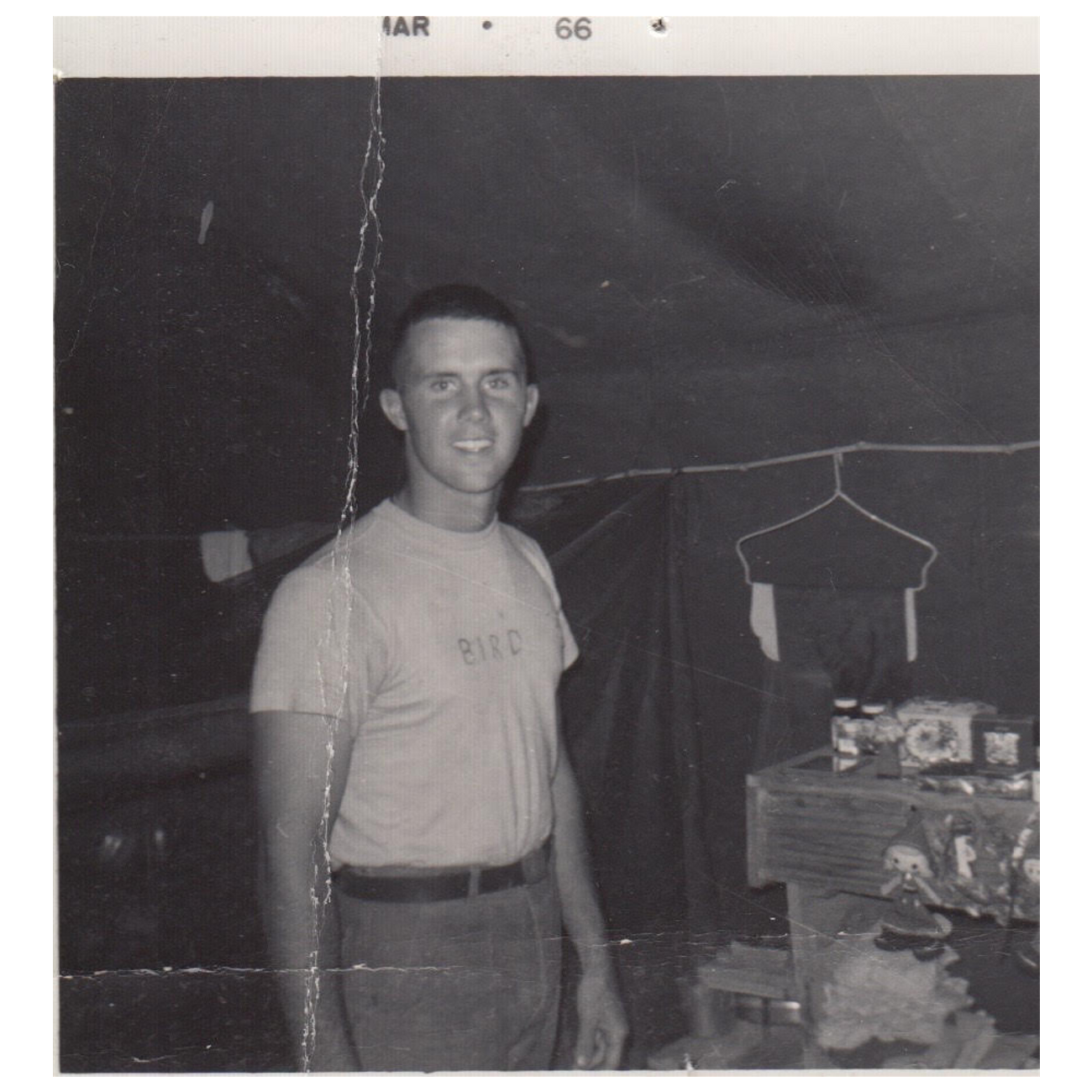

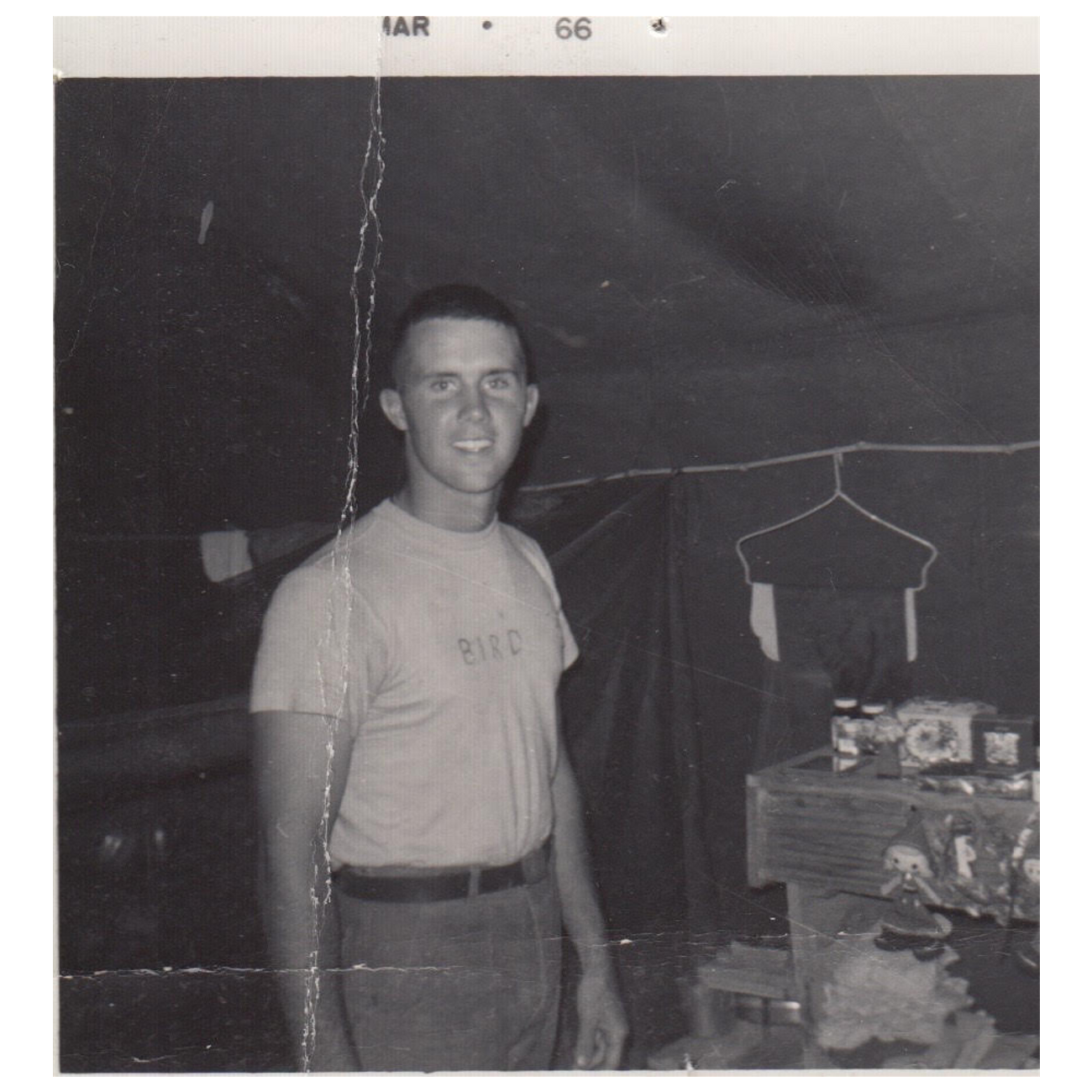

Imbued with WWII’s aura of justice and righteousness, eager to claim his place in a family heritage, Tom Bird enlisted in the Army for a two-year stint in late 1964. He was in Vietnam for 10 months of that time, ending when he was evacuated out with malaria in June 1966.

Entering college back on Long Island as a prized football recruit, Bird found himself called a “war criminal” during a student protest one day. He responded by punching the heckler and breaking his jaw. Convicted and sentenced to two years in Nassau County jail, Bird had the punishment shifted to mandatory psychiatric care, which included the drug Thorazine and electroshock treatments.

By the time Bird returned to campus in 1969, he felt alienated from everyone—protesters, veterans, football teammates. His only acceptance came from the theater geeks, and he ended up performing in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and then was typecast as a prison guard in Marat/Sade, acting opposite the same student he had assaulted two years earlier. One scene, in fact, called for Bird to strike him onstage. Filled with remorse, Bird told the director he wouldn’t do it. Then the fellow actor said to him, “You have to. It’s for the play. The past is forgiven.” After Bird thanked him, the actor added, “Just don’t hit me too hard. My jaw still hurts.”

That moment infused Bird with the sense that theater could heal him. He moved to Manhattan, tending bar and studying with the renowned Lee Strasberg. Then, in the mid-1970s, a Korean War veteran floated the idea of Bird assembling a theater troupe for his era’s ex-soldiers—largely as a way of getting those men paying work, since the stereotype of the ticking-time-bomb Vietnam vet was pervasive in the performing arts.

Bird took out an ad in a theater trade paper, and 40 veterans showed up for an initial meeting. Out of it grew Vetco, as the Vietnam veterans’ theater group became known. It burst onto the national theater scene, with Bird as its artistic director, in the 1985 show Tracers. Presented at the Public Theater by Joe Papp, himself a WWII veteran, Tracers largely drew upon the actor-veterans’ own experiences in Vietnam. Frank Rich wrote in the New York Times, “When a nation’s horror tale is told by its actual witnesses—and told with an abundance of theatricality, a minimum of self-pity—it can still bring an audience to grief.”

Two years later, under the aegis of HBO, Bird produced the documentary film Dear America, whose script was entirely composed of letters sent home by American men and women serving in Vietnam. “There have been a lot of movies made about Vietnam, some of them good,” wrote Hal Hinson in the Washington Post. “Now a great one has been made.”

Indeed, Bird and Vetco did something much more than make hit shows. Like other works of art created by or about Vietnam veterans—Ron Kovic’s memoir Born on the Fourth of July, Tim O’Brien’s debut novel Going After Cacciato, W.D. Ehrhart’s poetry, Bruce Springsteen’s acerbic anthem Born in the U.S.A.—Tracers and Dear America contributed to a major change in the American understanding of the Vietnam War. Those who lauded it and those who loathed it could now agree on a central, unifying premise: After a decade or more as pariahs, the men who fought it deserved their nation’s embrace.

During the years Bird was developing this body of work, two events occurred that set Bearing Witness into motion. In 1984, on the morning after confiding a secret about his time in Mauthausen to Tom, Sam Bird died. In 1989, when HBO was preparing to release a feature film about Simon Wiesenthal, The Murderers Among Us, Bird was introduced to the legendary Nazi-hunter at a press luncheon.

An HBO executive, who knew that Wiesenthal had been imprisoned at Mauthausen, mentioned that Bird’s father had helped there after liberation. Bird then recounted some of the few stories of Mauthausen he had gleaned from his father—the mass graves, the living people hidden among the corpses. Wiesenthal confirmed: Yes, it was all true. He had weighed less than 100 pounds at liberation. And he always remembered the tenderness of the American Army doctors.

“Have you visited? Wiesenthal asked Bird.

“No.”

“You must, to truly understand.”

Up until that moment, Bird explained, he had never even thought of it.

“Do it for your father,” Wiesenthal told him.

Seventeen years passed before Bird followed the admonition. In 2006, his godmother died and left Bird a small bequest. He used it to travel to Mauthausen. Although he had been working for years already on a memoir about himself and his father, Bird had not been a student of the Holocaust, beyond having seen Schindler’s List and the Claude Lanzmann documentary Shoah.

In the aftermath of his trip to Mauthausen, however, the Holocaust became the third leg of an evolving script, joined with Sam Bird’s service in WWII and Tom Bird’s service in Vietnam. The text grew to 100 pages, then shrank down to 40. An experienced producer and director—Barbara Ligeti and David Schweizer, respectively—came on board. There was never any question that Bird himself would perform the piece. He had gotten to know the brilliant monologist Spalding Gray when they acted together in the 1984 film The Killing Fields. (Bird gets mentioned in Gray’s one-man show about the movie and the Khmer Rouge genocide, Swimming to Cambodia.) And during the late 1980s and early 1990s, Bird had written and performed two first-person theater pieces, Walking Point and Point of Origin.

For anyone who sees Bird in Bearing Witness, it will be nearly impossible to conceive of any other actor doing it. The meld between real life and stage presentation is inseparable. Starting with that moment of discovering his father’s photograph of the victims at Mauthausen, Bird loops forward and backward in time and memory. The questions that compel his journey are these: Why was my father’s war so good and mine so bad? When I was suffering so much after Vietnam, why did my father just keep telling me to get over it?

Bird spares neither himself not anyone else in recounting his experiences in Viertnam. Several of the most wrenching events in Bearing Witness had been summoned up when Bird was being treated for post-traumatic stress disorder in 2008. A therapist then told him, “You have to go back to the one event that most traumatized you, that made you go numb.”

On a patrol near Cambodian border, Bird recalls in the play, his unit is ambushed by North Vietnamese soldiers. After most escape, one remains behind, wounded, but still holding a live grenade. Bird briefly makes eye contact before gutting the man with a bayonet. Then, checking over the body, Bird finds a photograph of the soldier with his wife and child and also a good-luck amulet of Buddha. “I instantly passed through the membrane to the other side of civilization,” Bird says in Bearing Witness, “not sure I’d ever be the same.”

In another incident, Bird leads an American patrol through a village of Vietnamese lepers. They appear friendly at first, but then shots ring out. Bird and his comrades start beating villagers at random and radio in for permission to fully attack. Instead, 30 minutes later, two South Vietnamese helicopter gunships swoop in, pouring thousands of rounds into the hamlet. “Explosions and screams came from the village we’d just terrorized,” Bird recalls in the theater piece. “We changed fast and wanted to shoot the gunships down. The first chopper banked out and the second one came with the same deadly symphony. … More screams, explosions, fires, and screams. We were ordered to stay put! It wasn’t American! We should’ve been helping them! I should’ve disobeyed! Watching this slaughter was unbearable.”

As relentlessly honest as Bird keeps his gaze on Vietnam, he similarly refuses to treat WWII through the rosy tint of “Greatest Generation” nostalgia. For all of Sam Bird’s insistence that his son put the war behind him, for all the father’s seeming equilibrium as a beloved suburban doctor, it turns out that he, too, has been futilely trying to silence the past. His persistent ulcer attests to his unsettled conscience.

In the theater piece, Tom Bird recalls visiting Mauthausen and thinking in free-associated fragments of the memories that his father had sporadically revealed:

Just past dawn … warm already … we came up a back road … the pungent odor of death and decay was everywhere in the air … engineers exhuming a hastily dug mass grave about a 100 meters outside the camp … over a thousand bodies … living people had been buried … rescued four Italian soldiers, only one survived … no water, sewage, food, power … hard to tell who was live … we knew if their eyes moved or they blinked … skin was jaundiced, yellowish, tore when we picked them up … too weak to move … they needed fluids … couldn’t find veins … they were covered in lice … eight in ten had typhus … diarrhea was rampant … frozen feet and gangrene … amputations … a woman begged for a cigarette … peeled off the paper… ate the tobacco, choked, couldn’t swallow, had to be rescued … used medicine droppers to feed them … liberated prisoners beat some hated kapos to death … buried 1500 in first week week … 1500 more the second … dying went on for weeks … we froze emotionally in order to work.

Sam Bird spent a month in Mauthausen after liberation. On a Sunday dinner in 1984, with a table set by his wife with their best linen and china and silver, he faced Tom and said, “I’ve never told this to anyone, son.” Then he spoke about the second week he was in the camp. One group of survivors seemed to be recovering well. Sam Bird figured he’d give them some milk, help their bones rebuild. Instead, 13 of them died. After all the years of forced starvation, their maladapted bodies reacted to so much nutrition by going into metabolic shock and cardiac arrest. On the morning after Sam Bird confessed all this, he died.

More than 30 years later, Tom Bird is left with the same ontological question that has haunted so many Jewish survivors of the Shoah. “I’m going to be 70 in September and I’m on a search for God,” he said during an interview. “I want to come to peace with God before I die. Doing this show, having this experience, is part of it. And if people like Wiesenthal, who went through the Holocaust, can come back to God, then so can I.”

Samuel G. Freedman is a journalism professor at Columbia University and a regular contributor to Tablet. He also writes the “On Religion” column for The New York Times.