Torchbearer

Emma Lazarus’ “The New Colossus” is a greater symbol of freedom’s light than the Statue of Liberty

We have been living with these lines for a long time—almost too long to think about them:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

It matters, as we shall see, to the meaning of the poem that these lines are inscribed in the figure of liberty herself: They are and were meant to be site-specific. “The New Colossus” is one of those good-bad poems whose luster is inseparable from its occasion. When American liberty was a hundred years old, the statue was commissioned; who can imagine another poem accompanying it? Emma Lazarus wrote the sonnet in 1883, and it is among her most memorable poems—the mature work of an author, then in her early thirties, whose first efforts came during the Civil War. Indeed, those “huddled masses” carry an echo of the most famous lyric of the Civil War:

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps,

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read His righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps:

His day is marching on.

The “imprisoned lightning” of the lamp held by liberty goes back to another line from the “Battle Hymn of the Republic”: “He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword.” These reminiscences of the Battle Hymn suggest a revolutionary memory at the heart of a poem otherwise extraordinarily sure of its peaceable intent. “The New Colossus” frames a thought about American liberty after the battles are done.

Lazarus, in other poems, built up a fable of the New World as a refuge for insulted dignity. Her “1492,” a sonnet closely related to “The New Colossus,” addressed the Spanish expulsion of the Jews:

Hounded from sea to sea, from state to state,

The West refused them, and the East abhorred.

No anchorage the known world could afford,

Close-locked was every port, barred every gate.

Then smiling, thou unveil’dst, O two-faced year,

A virgin world where doors of sunset part.

Even “the West refused them”—and they would have perished, except that there was a farther West. Incidentally, the phrase above explains the curious noun “refuse” in “The New Colossus,” so easily misread as a synonym for trash or detritus. The people who are “refuse” are simply those who have been refused entry elsewhere.

The imagination of Emma Lazarus worked familiarly with a contrast between the airless crush of immigrants forced into close quarters and the freedom of the city they would meet on the other side. As she put it at the end of “City Visions I”:

All day long,

Think ye ’t is I, who sit ’twixt darkened walls,

While ye chase beauty over land and sea?

Uplift on wings of some rare poet’s song

Where the wide billow laughs and leaps and falls,

I soar cloud-high, free as the winds are free.

Like other late Romantics, she believed in republican freedom and the religion of the heart; they went together naturally and might be known to each other under the name of “sympathy.” Her sonnet of that title speaks of her suffering of private woes; the “blots” on her “imperfect heart” are relieved when known and felt by others:

For this I know,

That even as I am, thou also art.

Thou past heroic forms unmoved shalt go,

To pause and bide with me, to whisper low:

“Not I alone am weak, not I apart

Must suffer, struggle, conquer day by day.”

This sense of company in solitude is not only an affair between person and person. It is communicable from one people to another: an idea that marks a strong undercurrent of “The New Colossus.” Americans, the poem says, must never forget what it is to be weak and comfortless. For me to know, through the workings of sympathy, that “heroic forms” have passed through a crisis like mine, can be a liberation in itself.

Republican radicalism in the 19th century went hand in hand with nationalism. And though the nationalist feeling is subdued in “The New Colossus,” it appears more overtly in “The New Ezekiel”: a sonnet Lazarus dedicated to the possibility of a Jewish homeland. From the prophetic text “Can these bones live?” she proceeds to the Lord’s injunction to “prophesy,” and rounds on the declaration:

The spirit is not dead, proclaim the word,

Where lay dead bones, a host of armed men stand!

I ope your graves, my people, saith the Lord,

And I shall place you living in your land.

It was the experience of reading George Eliot’s novel Daniel Deronda—as Esther Schor informs us in her Nextbook Press critical biography Emma Lazarus—that called forth Lazarus’ engagement with the idea of a Jewish restoration.

Yet “The New Colossus” is a poem about a kind of exile that is permanent and good. Liberty, in this poem, takes its meaning from the fact that the content of what is discovered away from home is always unknowable.

Liberty’s endless path, lit by the lady of the harbor, is pictured as a refuge from injustice. The poem draws here on the internationalism of Heine, and it owes a more particular debt to two sonnets by Shelley. “England in 1819” gave Lazarus a dense background of despotic horrors—an allusion mentioned in John Hollander’s fine discussion of “The New Colossus” in The Gazer’s Spirit. In 1819, the year of the Peterloo Massacre, Shelley had written to denounce

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn—mud from a muddy spring,—

Rulers who neither see, nor feel, nor know,

But leech-like to their fainting country cling

—where the shame of oppression belongs to rulers, not subjects. The decaying monarchies of the old world are hidden, and they seek the darkness, in lands dominated by

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay,

Religion Christless, Godless—a book seal’d,

A Senate—Time’s worst statute unrepeal’d.

Yet, for Shelley, all these abuses are finally legible only as “graves,” from which “a glorious Phantom may/ Burst, to illumine our tempestuous day.” Compare Lazarus’ quieter words: “I lift my lamp beside the golden door.”

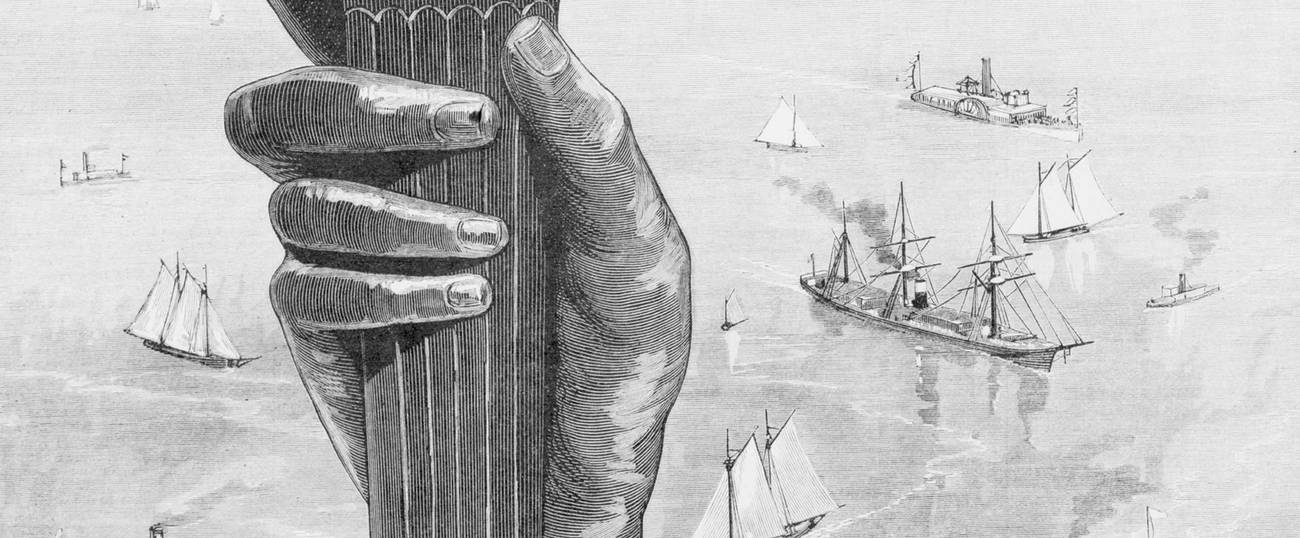

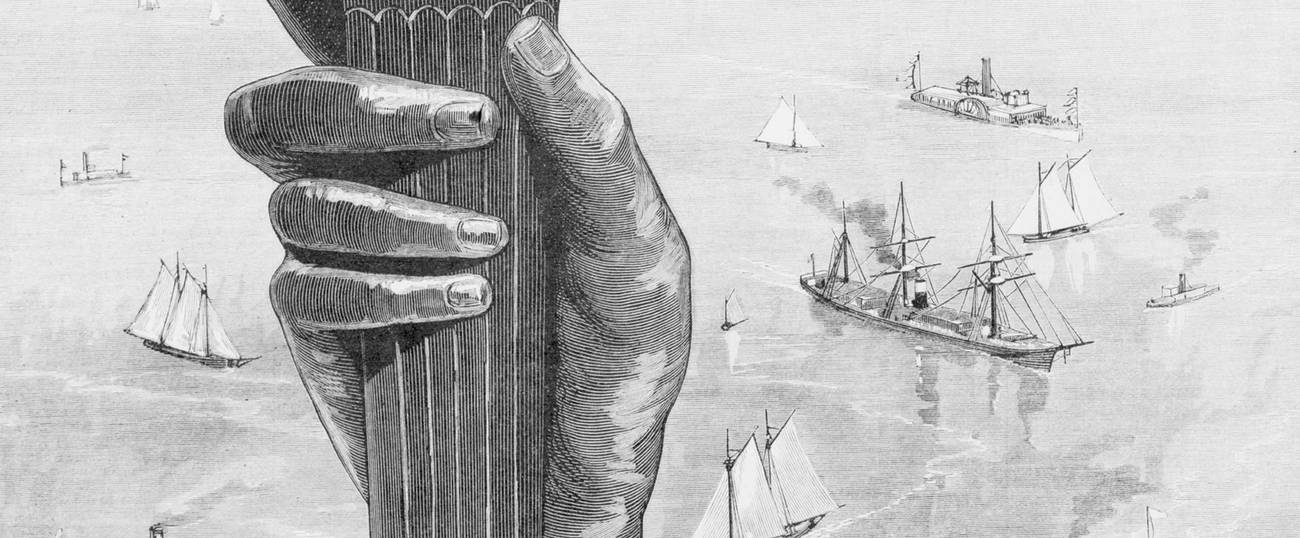

A stronger precedent for “The New Colossus” comes from Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” a familiar poem to the 19th century, whose opening lines describe a monumental ruin.

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things.

The image of the fallen glory of the tyrant brings to mind the “conquering limbs astride from land to land” of the colossus of Rhodes—a wonder of the world “The New Colossus” is pledged not to celebrate. The inscription explaining what is left of the king of kings, Ozymandias, forms the eleventh line of Shelley’s poem: “Look on my works ye Mighty, and despair!” A tyrant’s boast, which time and the ruins of empire have bleached dry. By contrast, the inscription that closes “The New Colossus” says nothing to posterity. Rather, it offers only a welcome after an uncertain passage. What lies ahead can only be what fate and the fortunes of the immigrants make of it.

A problem about inscriptions in poetry and in art generally is that we impute to them a speaker and an intention that the very idea of inscription keeps at a distance. So, it is not Poussin but Death, in his painting, that says “Et in Arcadia ego”; not Keats but the Grecian urn (its meaning, in so many other ways, elusive or ambiguous) that seems to say: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” So too the imperative uttered by liberty—“Give me,” “Send these”—is not what anyone could ever command, or sign a paper to warrant the truth of. It is just what we are to imagine liberty, the liberty of America, signaling to assist the oppression of people elsewhere. And we can imagine this for as long as we live by its light. It is an allegorical emblem whose truth is renewed by the conduct of American society.

Emma Lazarus, an ambitious artist of wide culture, would have been aware of the difference between Frederic Bartholdi’s Liberty Enlightening the World and the most famous earlier face of modern liberty, Eugene Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People.”

Delacroix’s picture was painted in autumn 1830, exhibited at the Salon in 1831, and placed in the Louvre in 1874. It is now the canonical image of French liberty: At the front of the crowd in the streets that overthrew Charles X, the last Bourbon king, she carries a bayonet in her left hand, and in her right the flag of France. Launched forward by the impetuous momentum of the crowd, she has a gathered strength—suitable to a leader who is mindful of those who follow. The Statue of Liberty holds neither a flag nor the sword or earlier emblematic depictions. She is equipped with nothing but the torch Emma Lazarus rightly made so much of.

The torch, the lamp, the imprisoned lightning, the “beacon hand” that glows “world-wide welcome”: These are the images that dominate the poem, and they go with the words that most people remember. “Give me your tired, your poor,/ Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” It is the poem itself, however, and not the statue that has made us think the Statue of Liberty a symbol of open gates.

Between them, “The New Colossus” and the statue it describes have given a reminder more vivid than a century of sociology to make Americans realize that we are a nation of immigrants. The lamp and the golden door mean the opposite of barbed wire, a border fence, a wall against feared and hated neighbors. The message of Lazarus and of Bartholdi too was simple enough: Liberty is the reverse of subjection. If America ever closes its gates, and if, in the name of safety, we ask the police to listen to our breathing and give us permission to breathe free, honesty would compel that we remove the statue from its harbor placement and house it in a distinguished museum somewhere.

David Bromwich is Sterling Professor of English at Yale.