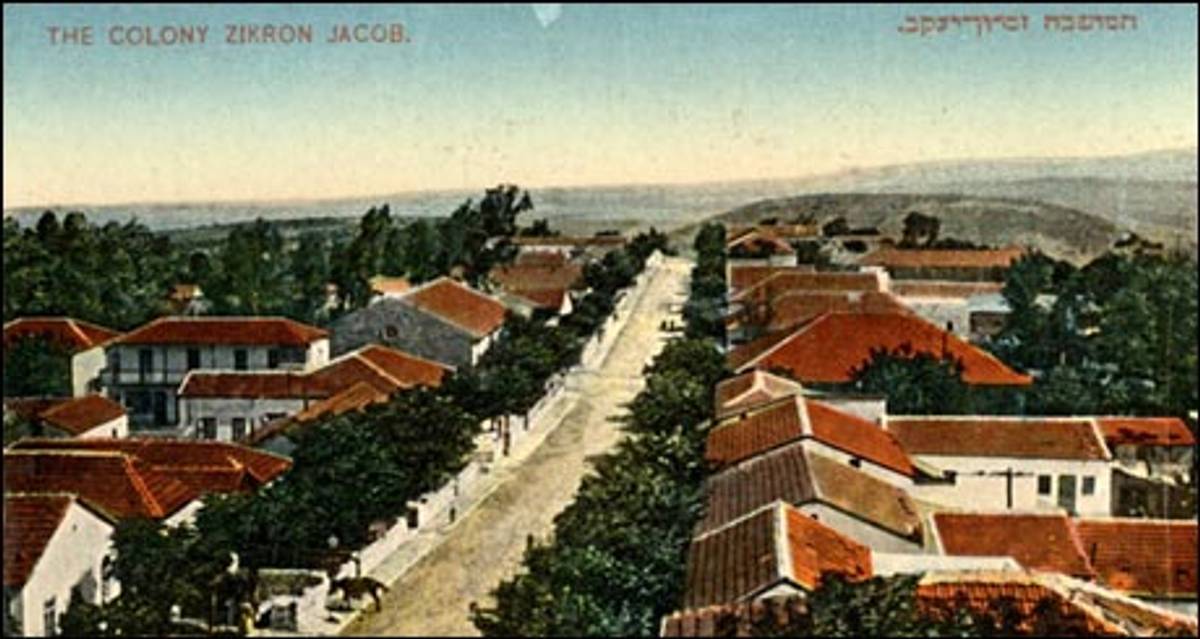

In 1970, Hillel Halkin moved to Zichron Ya’akov, a small farming village near Haifa, and swiftly became intrigued by its early history. The transplanted New Yorker befriended older residents, including a Virgilian guide named Yanko Epstein, who offered competing versions of the settlement’s beginnings. Halkin began to piece together the embellished recollections with fragments of documentation he tracked down. In A Strange Death, Halkin, at work on a biography of Yehuda Halevi for Nextbook’s Jewish Encounters series, describes how his enchantment turned to obsession as he sought to discover whether Zichron-based members of the Nili Underground pro-British spy ring were turned in by their neighbors, and whether one, Perl Appelbaum, was ultimately murdered for her betrayal.

The book feels a little schizophrenic—at once a memoir, a true crime story, a history.

It’s all those things and, I hope, more. It was conceived as a historical murder mystery, and would’ve been had I finished it in 1977 or ’78, when I began writing it. As time passed, I was having a lot of trouble writing. I had six or seven fat notebooks of material, all these conversations with people, exploratory walks and searches around town. I thought, “writing the book is going to be a snap. All I really have to do is copy the right passages from these seven notebooks and put a few interconnecting sentences. I’ll finish it in half a year.”

What I didn’t realize until I began writing was that there was a conflict between the facts and the problem of what to do with them—to make them aesthetically, dramatically pleasing, to create a successful story. Which is the same conflict that Epstein has. It was only in a very late stage of writing when I realized that connection. Epstein and I were engaged in doing something very similar. We were both liars pretending not to be liars. I’m like Epstein in many ways, which my wife accuses me of being at the end of the book.

You describe sneaking into basements and attics, prowling around abandoned houses. How did your wife feel about these shenanigans?

She wasn’t particularly happy about them. That whole period wasn’t happy for her. We were living a very isolated life, had moved to this town out of these crazy romantic impulses without really knowing what we were getting into. And suddenly, here we were on this hillside with this glorious view, but totally alone. We had South African neighbors whom we liked—practically the only people in town we had a relationship with—but they were older and childless, and we had two little kids. My wife didn’t have a driver’s license, we had no telephone. When I would go on my jaunts into town, sometimes for the better part of a day, that just made it worse.

Toward the end of A Strange Death, you suggest that Epstein is completely unreliable as a lay historian and as a narrator—and you never do get to the bottom of the murder. Doesn’t the truth matter?

In this case, not as much as I thought it did at first. When I began writing, I was obsessed with finding out what had “really” happened. Was Perl Appelbaum murdered? Looking back, that obsessive search for the truth was one of the things that bogged the writing down. If you’re writing straight history, of course, the truth matters enormously. But, in writing what was essentially a work of literature, at some point it struck me that the truth really did not matter, in terms of the book itself. History was only a vehicle. Utlimately I came to understand that whether or not Perl was murdered was of no intrinsic importance to the story I was trying to tell—which was about how you try to find out whether something happened, what memory does, what stories do to the past as we tell them. At the same time, the truth wasn’t entirely unimportant, in the sense that the book is written out of the conflict between telling the truth and telling a story.

At the same time, I would say to myself well, how can you use people’s real names, and then allow yourself to fictionalize certain things they said to you? Or to change knowingly, take a sentence that was said to you, and, and rewrite it in a different form, to play with the time frame? Can you allow yourself to do this? Or, if you do insist on doing this, why insist on clinging to real names?

Well, why did you?

I was writing about Zichron Ya’akov, a real place set against a well-known event, the Nili spy ring, and couldn’t really call Aaron Aaronsohn “Jacobson.” That would have seemed absurd and I had great affection for most of the pople I was writing about and wanted to commemorate them. It was very important to me to be trying to write about real people, even if I was changing certain things. And the tension between writing about real things and people and fictionalizing for aesthetic purposes seemed a very necessary part of what I was doing. I had the feeling that if I gave up that tension, I would lose that inner conflict that I was going through that was important in writing the book. I once said to someone that that conflict was like a coiled spring. I felt it was what drives the book forward and holds it back at the same time.

How this little village—which was composed largely of Jews from Romania, hardly a center of culture itself in the late 19th century—from the very beginning was tuned into the modern world in ways the Arab settlements around it never were. These early colonists led double lives. On the one hand, they were trying to fit into the world around them, trying to be farmers. But these were people who, by 1907 or 1908, had a movie house. The first automobile in the town was bought in 1912, a theater club performing Molière by 1920. They are constantly trying to keep abreast of things elsewhere—and make themselves part of the world. This would be inconceivable in the Arab villages. They stayed in the same villages, living the same customs, the same life from generation to generation. When you ask why the Jews of Palestine, when push came to shove, were able to defeat the Arabs, that’s a big part of the answer.

One doesn’t think of immigrants from small Romanian towns necessarily as sophisticates.

Eastern European Jewry in all its forms was acutely plugged into the modern world. And those of its members who came to Palestine were plugged into the modern world. And at the same time they wanted to be Jewish farmers and Jewish peasants in the Holy Land, they also wanted to be modern—they wanted to have everything that you had in New York or Paris. They didn’t want to be left behind.

You recreate scenes revealing a kind of cautious affinity between Zichron’s early inhabitants and its neighboring Arab populations. Is that really how they got along?

The First Aliyah certainly got along with the Arabs of Palestine much better than did the Second, whose history is better-known because it created the institutions of modern Israel. Zionist history was written by the Second Aliyah. In those days in old Zichron, every single person knew Arabic, how you behaved in an Arab home, their customs and values. It was taken for granted, just as the conflict was. Nobody had any illusions, in a village like Zichron in 1910, that there wasn’t a deep conflict. But everyone assumed that somehow, however it worked out, Jews and Arabs would be able to live together. The Second Aliyah, in which many Europeans came to Palestine with feelings of cultural superiority, made a great ideology out of Jewish-Arab brotherhood, but in practice did the opposite. It strove wherever it could to separate Jews from Arabs, to create all-Jewish institutions: cultural, economic, educational, and political.

Did your work as a translator help you acclimate to the new culture?

I met many Israeli writers because I was their translator, or because they wanted me to be their translator, but I’ve never moved in literary circles. For me, the most acculturating factor is bringing up children. When you’re an immigrant and you bring up children, you live through them the childhood that you never had there.

But here, I was an exception because I’d had such a Zionist childhood in America, so settling in Israel was never settling in a strange country. I went in 1948, 1949, 1950 to Camp Massad. We spoke Hebrew—were punished if we didn’t—and the songs we were learning were then being sung in Israel. The political discussions we were having were the political discussions that were being had in Israel. So when I came to Israel, I found myself at an erev shira (song night) and everyone was sitting around and singing songs from the thirties and forties and I knew them from my own childhood. Unlike immigrants who have to abandon their childhoods—you know, leave them behind—for me settling in Israel was recovering my childhood.

What made you leave the United States?

Two things went into the decision. On the immediate level, I visited Israel with my wife shortly after we married in 1968, which was an era of great euphoria, right after the Six Day War. The country was still dizzy with the triumph. There were all kinds of new places to go. I had been in Israel several times before, and found it unbearable to be there as a tourist. I felt such a sense of belonging, but at the same time not to feel part of it, and to know that you’re defined as not part of it—I couldn’t bear it. I remember very clearly saying to myself, either I come back here to live or I’m never coming back.

The more long-term thought was, I was never able to take American Jewish life very seriously. When I got married in 1968, it was clear to me that if I was going to live in America, I was not going to be part of the Jewish community or to raise my children in it. So that decision to live in Israel was a decision whether to live as a Jew or not, in some deep sense, to be Jewish or not. And when I thought about it deeply I had no choice—I didn’t have the choice of not being Jewish.

Today, 35 years later, I still feel that way. I really think that the significant future of the Jewish people is tied in with Israel. Why, when we are sufficiently privileged to live in a time when we could actually live in a Jewish state, with all the difficulties and heartbreak that may involve, to be really at the center of Jewish history, why choose to be in New York, or Minneapolis, or Chicago? That choice seems fundamentally perverse.

It calls to mind the wish from the Passover Seder—”Next year in Jerusalem”—less the rebuilt temple. That dream can be realized right now and yet so few move.

One of the many things that the State of Israel has taught us is that this is a fantasy more than a dream. Most Jews never mean it. You might prefer to dream of it than to live in reality. And Israel, I think, is in many ways, the psychiatrist’s couch to the Jewish people. Just lay down there, and discover a lot of things about ourselves that we didn’t want to know before.

It sounds like you’re saying that, by virtue of living in Israel, one almost acquits oneself of being Jewish.

That’s true, in many ways. One certainly acquits oneself of having to try so hard. One of the wonderful things about Israel is that it does take some of that burden of being Jewish off you, simply letting you live as a part of a Jewish society, sharing in all the problems. When one speaks of assimilated Israelis, you have to remember that it’s a metaphorical statement, compared to the American Jewish community. No Israeli is as assimilated as an assimilated American. There’s no comparison. Everyone in Israel gets that lowest common denominator. What you do with it afterward is your own choice. It’s like the difference between a regular table and a billiard table. On a billiard table, there are sides, you can never fall off. You can end up in a corner, but you’re always on the table, if we think of the table as some kind of Jewish consciousness. In a society like America, you get to the edge, you fall off.

Sara Ivry is the host of Vox Tablet, Tablet Magazine’s weekly podcast. Follow her on Twitter @saraivry.

Sara Ivry is the host of Vox Tablet, Tablet Magazine’s weekly podcast. Follow her on Twitter@saraivry.