Transgendering Stonewall

The intersectional left revises the history of the gay rights struggle in service of a political agenda that finds virtue in marginalization

Was Anne Frank “bisexual?” Keen to claim her as one of their own, some queer activists are citing previously overlooked passages from the complete and unabridged second edition of Frank’s diary as evidence that the world’s most famous Holocaust victim swung both ways. “I remember that once when I slept with a girl friend I had a strong desire to kiss her, and that I did do so,” Frank wrote about a sleepover with her best friend. Disregard, if you can, the strange fixation with the sexuality of a hormonal adolescent girl; seizing upon the private musings of a 14-year-old about her school crush as prima-facie evidence of bisexuality does little to illuminate, and much to occlude, the reason she and her family were hiding in the attic, which is that they were Jews. It is of a piece with other, modish forms of historical revisionism driven by contemporary political demands, like the claim that Muslims are “the new Jews,” that Syrian refugees are the modern-day equivalent of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany, or that detention centers holding individuals who voluntarily cross the internationally recognized border of a democratic country are akin to “concentration camps” where people—based upon their ethnicity—were forcibly herded prior to their mass extermination at the hands of a ruthlessly efficient totalitarian state.

A similar process of historical obfuscation is under way with regard to the Stonewall Uprising, which transpired 50 years ago last month when the patrons at a Greenwich Village gay bar fought back against the police harassment that intruded so heavily upon gay life at the time. According to the revisionist narrative, it was not gay people who sparked the rebellion, but “trans women of color.” Writing to commemorate the rebellion in The New York Times, the director of policy and programs at the Transgender Law Center describes Stonewall as the place “where trans women of color led the resistance that started the national L.G.B.T.Q.-rights movement.” In a symposium for Harper’s magazine, a transgender author named T Cooper declares, “If it were not for us, Stonewall might not have happened.” The National Center for Transgender Equality contends that, “Although the exact identity of the person who started the riots is lost to history, we know that trans women, especially trans women of color, played a central role in the resistance.”

Topping a recent New York Times list of “LGBTQ Pioneers” deserving of statues in their honor is the late Marsha P. Johnson, who variously identified herself as a gay man and a drag queen, and whom the paper credits with “spearheading the rebellion at Stonewall as a transgender African-American woman.” Two weeks later, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio heeded the call by announcing that Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, another transgender activist often credited as leading the insurrection, would be honored with a statue in the vicinity of the old Stonewall Inn. “Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera are undeniably two of the most important foremothers of the modern LGBTQ rights movement, yet their stories have been erased from a history they helped create,” declared New York City’s first lady, Chirlane McCray, in a statement lauding the pair’s “leading role at Stonewall.”

Stonewall revisionism has even reached the upper echelons of the gay mainstream establishment, with the Human Rights Campaign, the country’s leading LGBT advocacy group, and Mayor Pete Buttigieg, the first serious openly gay presidential candidate, mouthing its mantras. “Harassed by local police simply for congregating, Stonewall’s LGBTQ patrons—most of whom were trans women of color—decided to take a stand and fight back against the brutal intimidation they regularly faced at the hands of police,” asserts an article on the website of HRC. Buttigieg, no doubt smarting from accusations that he’s not gay enough, last month tweeted that “#Pride celebrates a movement that traces back to the courage of trans women of color 50 years ago this weekend.”

The release three years ago of the coming-of-age docudrama Stonewall, which placed a blond, cisgender, white gay man at the center of events, gave a significant, if inadvertent, boost to those who falsely assert that “trans women of color” started the uprising, only to have their leading role erased by a Hollywood whitewash. That it was most likely a blond, cisgender, white gay man, Jackie Hormona, who threw the first punch at a cop did nothing to quash the fake news. “By many accounts, the rebellion was led by drag queens and gay street people,” wrote a film critic for The New York Times, arguing that the movie’s “invention of a generic white knight who prompted the riots by hurling the first brick into a window is tantamount to stealing history from the people who made it.”

The narrative that “trans women of color” led the Stonewall riot rests largely upon the purported participation of just two individuals: Johnson (who was black) and Rivera (who was Hispanic.) One popular story, recently repeated by transgender actress Laverne Cox in the ABC documentary series 1969, has it that Johnson was celebrating her 25th birthday at the bar when police raided the joint. In an article published three years after the uprising, Rivera maintained that “the first stone was cast by a transvestite half sister. … Remember we started that whole movement the twenty-seventh day of June of the year 1969!”

***

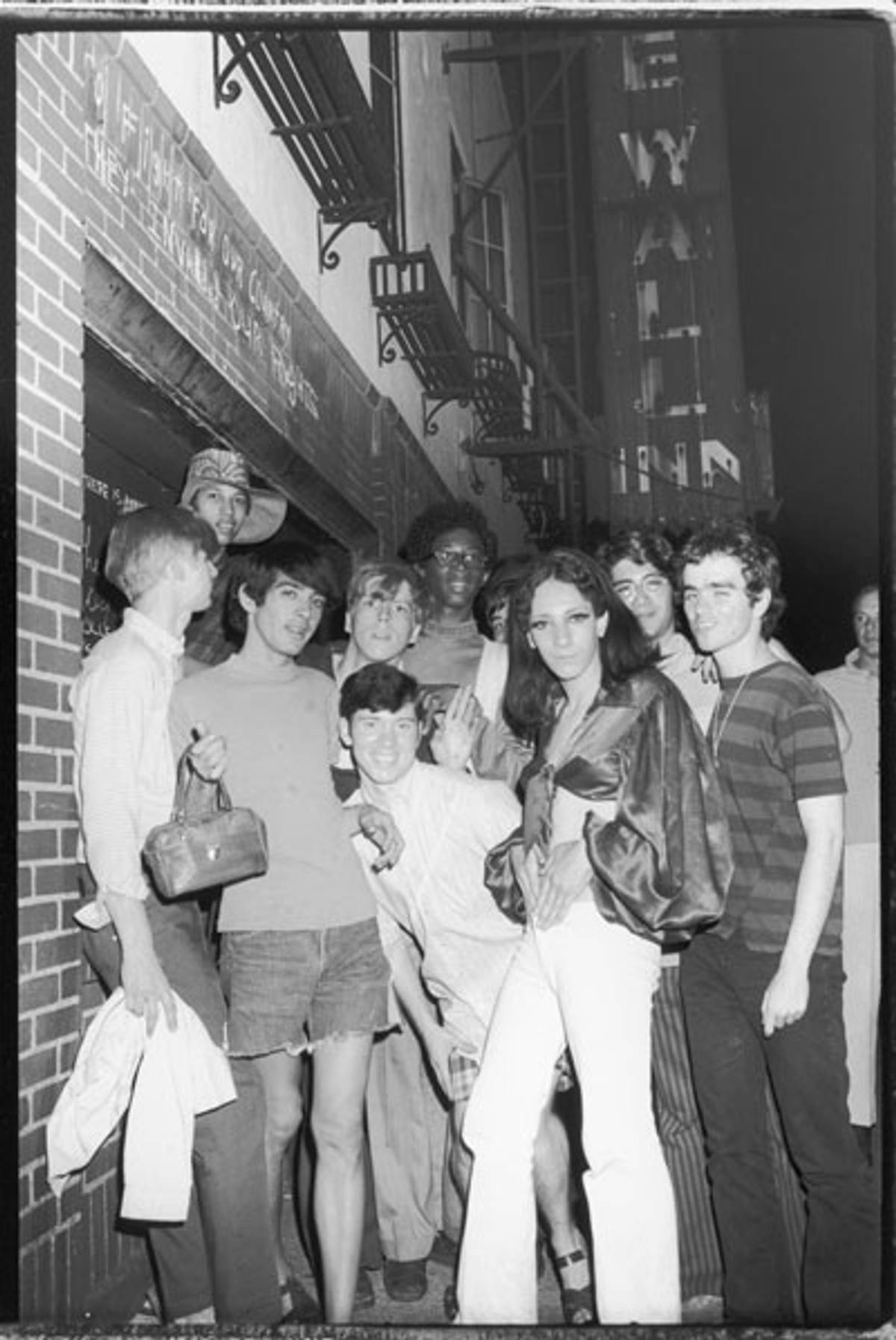

Contemporaneous press accounts and the most credible scholarship both confirm that the crowd which partook in the Stonewall uprising was primarily not trans, female, and of color, but gay, male, and white. “Hundreds of young men went on a rampage in Greenwich Village,” the Times reported the day after the uprising began, using “young men” repeatedly to describe the rioters. A story in the next day’s paper again referred to “large crowds of young men” engaged in fisticuffs with police. The Village Voice reported that, of the 200 people ejected from the Stonewall Inn the first night of the riots, only five people dressed as women were arrested.

“My research for this history demonstrates that if we wish to name the group most responsible for the success of the riots, it is the young, homeless homosexuals, and, contrary to the usual characterizations of those on the rebellion’s front lines, most were Caucasian; few were Latino; almost none were transvestites or transsexuals,” concludes David Carter in Stonewall, the definitive account of the uprising, for which he conducted hundreds of interviews. Carter quotes one of the bar’s owners stating that its clientele was “98 percent male.” As for the presence of transgender people, the Stonewall was “not a generally welcoming place for drag queens,” Eric Marcus, editor of an oral history of the gay rights movement, wrote in 1999. “The majority of the hundreds of people who crowded onto Christopher Street and jammed Sheridan Square were young gay men.” In his 1996 book American Gay, the sociologist and anthropologist Stephen O. Murray writes that “men familiar with the milieu then insist that the Stonewall clientele was middle-class white men and that very few drag queens or dykes or nonwhites were ever allowed admittance.” Sylvia Rivera herself once told an interviewer that “The Stonewall wasn’t a bar for drag queens. … If you were a drag queen, you could get into the Stonewall if they knew you. And only a certain number of drag queens were allowed into the Stonewall at that time.”

Put aside the question of whether the people described as “draq queens” 50 years ago would today identify as transgender (some might, many would still identify as drag queens, that is, gay men impersonating women)—by most accounts they were relatively few in number. “There were maybe twelve drag queens,” one participant, Craig Rodwell, recalled in an interview years after the uprising, “… in thousands of people.” Speaking in a New York Times video essay about the disputed legacy of Stonewall, another participant, Robert Bryan, states that “There were some individual people of color but it was not a group of trans people of color who started the rioting.”

As for Johnson and Rivera, their role in Stonewall has been greatly exaggerated. Often credited with having thrown the first brick (or shot glass, pick your legend), Johnson’s own accounts contradict the narrative that others have propagated in the decades following her 1992 death. By her own admission, Johnson wasn’t even at the Stonewall until well after the rioting began (and her birthday was in August, not June). Johnson told Eric Marcus: “I was uptown and didn’t get downtown until about two o’clock. When I got downtown, the place was already on fire, and there was a raid already. The riots had already started.” As for Rivera, who died in 2002, there is “not one credible witness who saw her there on the first night,” according to the historian Carter. One of Carter’s sources who was present when the fighting broke out told him that Johnson herself later said that “Sylvia was not at the Stonewall Inn at the outbreak of the riots as she had fallen asleep in Bryant Park after taking heroin.” The historian Martin Duberman, author of another book about Stonewall, calls Rivera “wildly unreliable.”

Rewriting the history of Stonewall as a primarily transgender event is to avoid all the hard work required of any successful social movement.

Transgendering Stonewall serves a contemporary political agenda, one that asserts a proportional relationship between marginalization and virtue. As America has essentially come to accept gay equality, the intersectional left—perpetually in need of an adversarial posture against society, and for whom “trans women of color” is now a slogan—has settled on radical gender ideology as its next front in the culture war. Stonewall loses its cachet as an inspiration for contemporary “resistance” if it retains its actual gay character, as that renders it achingly bourgeois, and so the event has been distorted into a transgender story, thereby making it more subversive. (And even that isn’t enough for some people: According to one historian, Stonewall wasn’t just led by trans women of color, it was “a Race Riot against the police started by hustling transwomen of color.”) Witness Julian Castro’s expressed commitment at last month’s Democratic presidential debate to providing federally funded abortions for a “trans female.” Despite being an anatomical impossibility, it was one of the night’s most raucous applause lines.

As political strategy, it’s understandable that some transgender activists would want to conflate their cause as much as possible with that of the gay movement, which has achieved more social change more rapidly than any other in American history. The transgendering of Stonewall stems from an entirely understandable impatience with the evolution of public attitudes on the subject of gender identity, and an expectation that Americans should accept the claims of the transgender movement as readily and as fully as they did those of the gay one. But this desire to imitate the successes of the gay movement lacks an appreciation for its long-term strategy and tactics. It took five decades from the first gay rights picket outside the White House in 1965 to the national legalization of same-sex marriage. In the intervening years there were numerous victories and setbacks: The removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental disorders was followed by Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign; the unexpected defeat of a California ballot initiative prohibiting gays from teaching in public schools was overshadowed weeks later by the assassination of Harvey Milk; the AIDS epidemic, the 1986 Supreme Court decision Bowers v. Hardwick upholding state bans on gay sex, and the imposition of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” on the military did as much to stigmatize gay people as Angels in America, Ellen, and Will & Grace did to humanize them. Whatever dignity gays have earned in the eyes of their fellow citizens has come about through a painstaking, decades-long process of individual gay people coming out and explaining themselves to the American public, a process that is ongoing.

The transgender movement has been visible for a far shorter period of time, and presents a far more conceptually challenging predicament to society, than that posed by homosexuality. And yet many of its most vocal advocates expect Americans to accept unhesitatingly its claims, yesterday, and deems those who do not Nazis. Rewriting the history of Stonewall as a primarily transgender event is to avoid all the hard work required of any successful social movement.

Gay people have been lied about for millennia—by organized religion, by the medical establishment, by the media, by governments. Much of our history remains in the closet, hidden by generations of enforced secrecy and private shame. That this latest bit of deceit comes from another constituent in the LGBT acronym doesn’t make it any more acceptable. “If people start telling stories not as they were but as they would like them to be, that procedure can be used by anybody for any purpose,” Robert Bryan, the Stonewall veteran, told the Times—words that those who perpetually bemoan our truthfully challenged president would be especially well advised to heed.

What might have been a laudable effort to highlight the role of transgender people alongside gay people in a major historical event has been corrupted by an effort to expunge gay people, and gay men in particular, from that story. After the AIDS epidemic nearly destroyed a generation of gay men, the stealing of Stonewall amounts to a second erasure.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

James Kirchick is a Tablet columnist and the author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington (Henry Holt, 2022). He tweets @jkirchick.