A Psychedelic American Passover

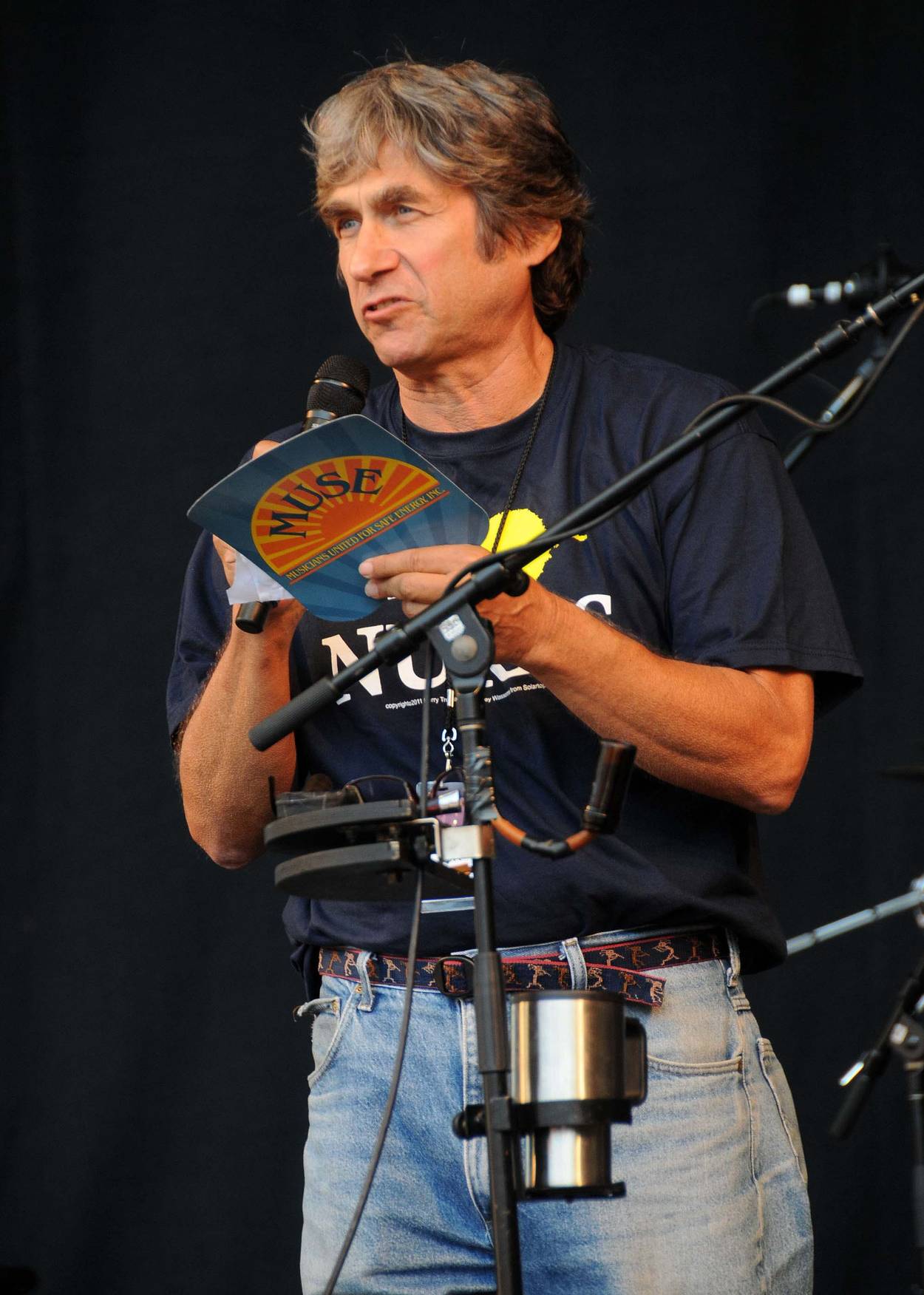

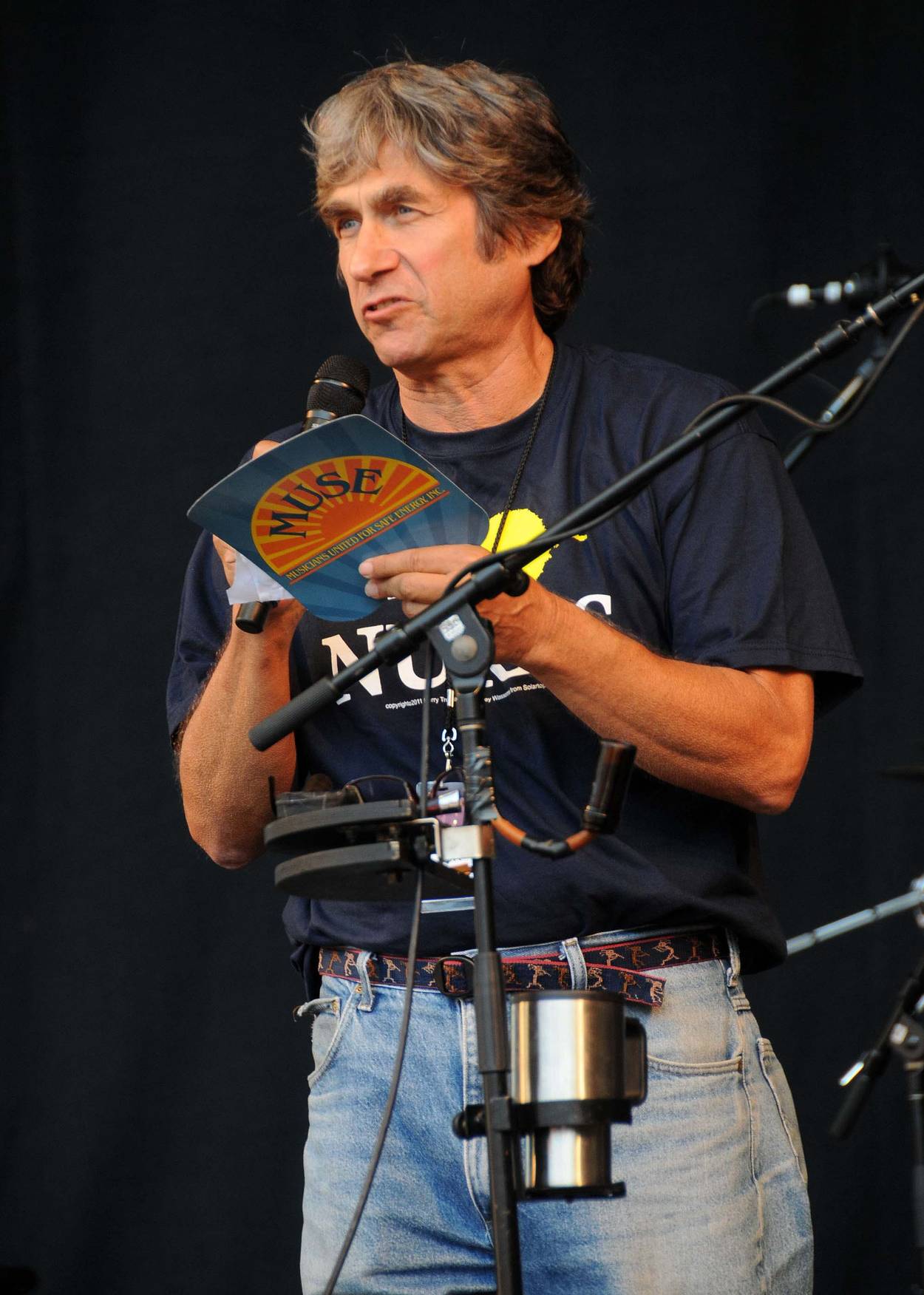

A trip through American history with ’60s historian Harvey Wasserman

Harvey Wasserman has a new book, The People’s Spiral of U.S. History, which he began in 1970 and that he finally finished in 2022. Part rabble-rouser and part tummler, the finished product is a history book like no other. There will never be one like it again, either.

For starters, he divides U.S. history into six periods, including “Infant Empire,” which covers the years 1688-1828, “Bully Manhood” from 1896-1932, and “National Senility” between 1976 and 1992—though the book is so up-to-date that it mentions Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The work is infused with humorous quips. “Can we walk and chew gum at the same time?” he asks in the last section, “Survival of the Greenest.” Eric Foner, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, calls it “zany, psychedelic, feisty, opinionated.” All that is true. Wasserman himself calls his book “Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the U.S. on acid.” Wasserman knew Zinn. He also took LSD.

In 1972, Wasserman—an American Jew and a Jewish American, a hippie intellectual and an intellectual hippie—wrote and published Harvey Wasserman’s History of the United States with a preface by the equally feisty, anti-establishment Zinn. Rolling Stone gave the book a rare review. That 1972 volume began with the Civil War and ended with World War I, and it sold well. The book’s popularity and Wasserman’s own curiosity persuaded him to expand the time frame and take in all of U.S. history. But he “fell into a rabbit hole,” as he puts it, and couldn’t get beyond the period of history that he loved the most, with its bohemians and robber barons, the heroes and villains of his narrative.

Wasserman wasn’t merely lost in Wonderland. After spending some time on a commune in rural western Massachusetts, he worked, married, raised a family, and did his best to get into “good trouble.” With a B.A. from the University of Michigan and an M.A. from the University of Chicago, he taught U.S. history for 14 years at the college level. He learned the subject matter inside and outside and upside down. As his new spiral history indicates, facts, figures, and dates are at his fingertips. He offers colorful anecdotes; no story is too trivial for him if it reflects the true character of American politicians and political figures from Alexander Hamilton to William Jennings Bryan and Woodrow Wilson. Wasserman is on a first name basis with the founding fathers: He calls Jefferson “Tom” and Benjamin Franklin “Ben.” Eugene Victor Debs is “Gene.” Wasserman himself was nicknamed “Sluggo” when he first played softball years ago. It has stuck with him.

After his commune stint, Wasserman became an outspoken anti-nuke activist. More recently—in the wake of what he and others have called the “stolen election of 2004” which put Bush II in the White House—he began campaigning against voter suppression and for fair elections. In Wasserman’s view, and in his spiral history, the villains aren’t only the robber barons of the Gilded Age. They are also notably the Puritans and their descendants. His heroes are the indigenous people of North America, from the Pequot to the Hopi and the Eskimo. Wasserman doesn’t have a good word for the Puritans, though he bears some resemblance to Roger Williams, the 17th-century Puritan minister and theologian, who rebelled against the Puritan patriarchy that accused him of heresy and forced him into the wilderness where he lived close to the Indians and where he created an unorthodox church of his own.

One of Williams’ enemies denounced him as “a firebrand.” Wasserman’s foes might use the same word to describe him. His new book is as fiery as a book can be without going up in flames. Over the past several decades, he has not mellowed. When I interviewed him by phone recently he sounded like he was still on fire at the age of 76 (he was born the last day of 1945), and not slowing down. With a name like Harvey Wasserman I knew he had to be Jewish. So, it was with Judaism and Passover on my mind that I began my conversation with him.

Jonah Raskin: Are you celebrating Passover?

Harvey Wasserman: Of course I am. While I’m spiritually Buddhist, I’m tribally Jewish. Buddhism has a core practice. You meditate. Judaism is all over the map. You go to one synagogue and the men are all standing and talking and to another synagogue where they’re all sitting quietly. I love Buddhism for its simplicity. Buddhism is where many Jews have gone to chill.

I was raised Jewish. I have a Jewish family of my own that includes my five daughters and their husbands who run the show at Passover. My own grandparents were from Latvia and Lithuania. They came to this country to escape the pogroms and ironically thereby escaped the concentration camps of the 1930s and 1940s. Both of my wife’s parents, who were born in Czechoslovakia, were concentration camp survivors. With that history, it’s not possible to forget one’s Jewish identity and Jewish traditions. My whole multigenerational family is conscious of its Jewish heritage.

JR: What does Passover mean to you?

HW: Freedom! Escape from Egypt and from oppression.

JR: Who are your Jewish heroes?

HW: Sandy Koufax and Bernie Sanders, Abbie Hoffman and Amy Goodman. There are lots of Jewish leftists in American history, such as Meyer London, a congressman from the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and Victor Berger from Wisconsin, one of the early founders of the American socialist movement. Berger served three terms in Congress. He and London are not widely known, but they played important roles as Jews and as socialists in the early 20th century.

JR: You seem to look at the past through the prism of the present day and especially through the lens of Donald Trump.

HW: Trump is a unique American character. He wasn’t our worst president. That was Woodrow Wilson, a real bigot. After 200 years of history, we finally had an outright mobster in the White House, beginning in 2016. Trump is a product of the mob and organized crime, though not the Mafia. There’s a difference. Trump is not a made man, but he has big mob connections, thanks in part to Roy Cohn, Joe McCarthy’s sidekick.

Trump is also owned by Putin. If our founders could meet Trump they’d be disgusted. Benjamin Franklin would be repelled. I don’t love Ronald Reagan, but Reagan had charm. It was really Nancy, not Ronnie, who ended the Cold War. She was also pro-choice. Everything she did was based on astrological charts.

JR: Your history book is one of a kind, though it stands on the shoulders of previous historians, and in your new book you credit them, including Howard Zinn, Staughton Lynd, and Charles Beard who blew the cover that surrounded the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in his controversial book An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.

HW: Another historian who influenced my thinking was Jesse Lemisch who helped to pioneer history from below and who died in 2018.

I heard Lemisch speak in Chicago in 1967 about the common people and about the political ideas and beliefs of American historians, which no one had made public.

Then there was William Appleman Williams, the author of The Contours of American History, a great book. My own thinking has been inspired by his basic idea that there’s been a cyclical dialectic in the U.S. between those two polar opposites, the indigenous people, who were democratic and egalitarian, and the Puritans, who were apocalyptic and who hated nature. A continual back and forth between those two camps has gone on for centuries.

JR: What drew you to the study of history in the first place?

HW: I have always loved history, especially the stories of unintended and unexpected consequences, like how the CIA helped introduce LSD to the counterculture. At Stanford, Ken Kesey took LSD while it was still legal and when the CIA was conducting experiments with acid. Then with the help of the Merry Pranksters, Kesey spread it around the country. Not what the CIA intended.

JR: Where are we going as a people and as a nation?

HW: Some pundits compare the U.S. of today with Germany in 1939. They point out that the Republicans are a neo-Nazi party and the Democrats a Weimar-like party. There are similarities, but there are also major differences. The U.S. is far more diverse ethnically than Nazi Germany. By 2050 a majority of the population will be nonwhite. Demographically, Texas and Florida will be remade. Germany in the 1930s was all-white. Hitler didn’t have Black people to persecute.

JR: But in the 1930s, there were about 500,000 German Jews.

HW: And the Nazis exterminated them. In the future, I see a life and death struggle on the one hand between the Steve Bannons of the world and the fascist elite in this country, and on the other hand, the boomers and millennials who favor democracy. We’re not going back to the 1950s. Culturally and spiritually we have left Egypt!!

JR: Happy Passover!

HW: The same to you and many more.

Jonah Raskin, professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of 14 books, including biographies of Jack London, Allen Ginsberg, and Abbie Hoffman. His new book of poetry is The Thief of Yellow Roses (Regent Press).