The Safdie Brothers Meet Crazy Eddie

Why ‘Uncut Gems’ succeeds as a portrait of a street Jew, but fails as art

In the 1980s, you couldn’t turn on a television in New York City without seeing an advertisement for Crazy Eddie’s discount electronics chain. The ads featured a fast-talking pitchman who rattled off appliance sales in a cadence between carnival barker and auctioneer, climaxing with the tagline: “Crazy Eddie, his prices ARE”—pause—“IN—S-A-A-A-NE!” The star of the ads was a white-haired former radio DJ named Jerry Carroll. But Eddie was Eddie Antar, a Syrian Jew from Flatbush who turned a single store in Brooklyn into the largest retail electronics chain in the New York metro area with annual sales over $300 million.

Even with Carroll as the frontman on TV, there was an unmistakable aura in the Crazy Eddie persona, a mix of streetwise come-up, unembarrassable brashness, and screwball comedy, that I saw instinctively as a familial relation. It reminded me of certain cousins and uncles and stories about the old days when life was still all about making it. The craziest part of the Eddie saga turned out to be the stock fraud that made Antar so much money he was flying it out of the country in bundles strapped to his body. Eventually, the Feds closed in and Antar, who’d tried to hide out in Israel, was extradited, pleaded to a racketeering charge and spent almost seven years in prison. It’s bad to defraud people, I can see that, but I placed Crazy Eddie Antar somewhere beyond ordinary morality as a quintessential figure of New York City lore, like Bernie Goetz, Robin Byrd, and the Wu-Tang Clan. He died in 2016.

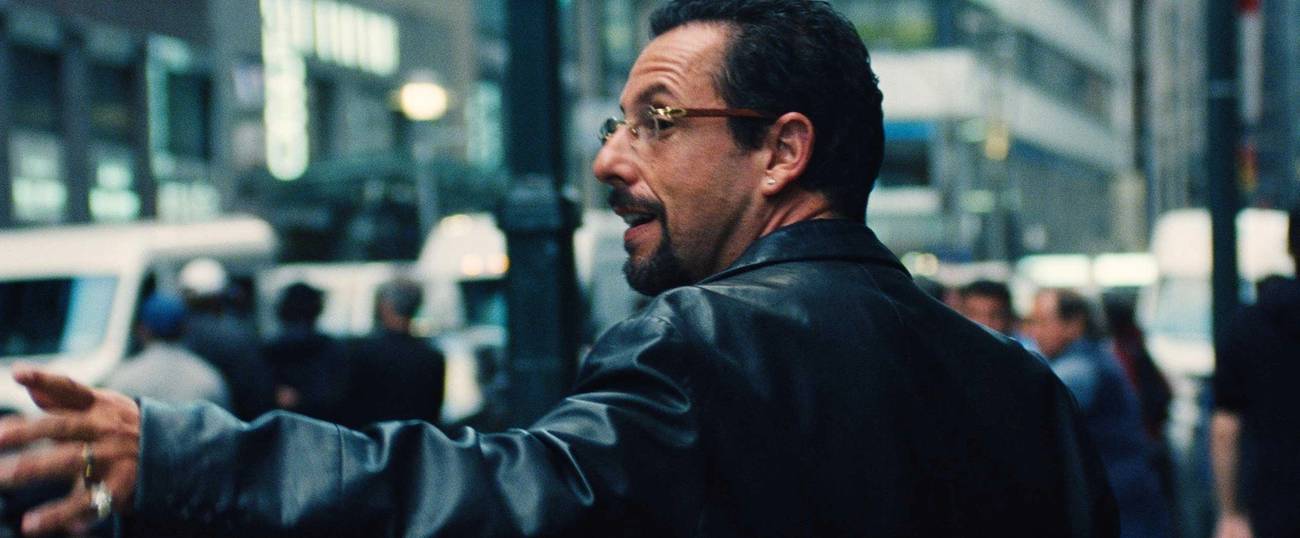

I hadn’t thought about Crazy Eddie in years until I watched the new Safdie brothers’ film, Uncut Gems. Now I can’t get him out of my head. I can’t get Uncut Gems out of my head either. The film stars Adam Sandler as the shady gem dealer, Howard Ratner, whose life veers wildly from madcap to tragic and, like Crazy Eddie’s, fits within a New York City Jewish American hustler archetype. If one wasn’t fictional and the other wasn’t dead, they could be cousins.

Queens-born writer-directors Josh and Benny Safdie, distant cousins of the famed Syrian-Israeli architect Moshe Safdie, have made some of the most original and exhilarating films of the past decade. Their style feels like neon realism. Using lurid, immersive storytelling, they capture sharply observed details about characters on the margins of New York City and make them stand out in the midst of chaos. It turns going to the movies into an active experience and allows the filmmakers to portray social issues like heroin addiction, without the uptight overtness that makes so much contemporary art feel dead on arrival. The approach has paid off, winning over critics and tastemakers, even as the Safdies ignored the reigning cultural ethos and accepted the risk of being criticized for “irresponsible” aesthetic choices.

There hasn’t been a vital piece of popular culture that was this explicitly and significantly Jewish in a long time. Thank the 2008 financial crash for that; the film dramatizes the old struggle to reconcile Jewishness, capitalism, and assimilation that was revived after the economic collapse, and is itself a product of the anxieties stoked by that struggle. It’s also a preview of how those anxieties will play out as they intensify in a political arena where Bernie Sanders, Michael Bloomberg, and Donald Trump all play to different Jewish archetypes and fears.

The film opens on an aerial shot of a sunbaked African landscape. A title card announces that we’re at the Welo mine in Ethiopia before the camera drops down into a group of angry miners crowded around a co-worker’s mangled body. In the chaos, as the mine’s Chinese foremen try to calm things down, two Ethiopian workers slip away. Inside a dark cavern, with the glimmering, cosmic notes of a Moog synthesizer setting the mood, the two miners chisel a black opal out of the rock wall. It falls to the ground and, for a brief moment, glows in their hands like an otherworldly talisman, before they secret it away to be smuggled to New York.

Moving the action from Africa to New York, the camera zooms inside the stone. Passing through the iridescent color patterns of the opal’s core before transporting into the tunnels of a human organ, the shot pulls out to reveal Howard lying on his side on an exam table while a doctor pilots the micro camera performing his colonoscopy. Moving from gem to colon, it’s all connected—labor, commodity, exploitation, wealth, and rotting flesh—within some larger system of late capitalism, as the film disappears briefly up its own ass.

“Holy shit I’m gonna cum,” Howard says when the opal finally arrives at his shop. It’s one of the few moments of release in two hours of relentlessly building tension, as Sandler’s clenched face relaxes into the wide-eyed glee of his goofy comedic roles. The Jewish diamond dealer figuratively ejaculates over his precious stone, its dark magic purchased with the spilled blood of the nameless African miners. But we’re in New York now and as gross as Howard may be, he’s at the center of an intense, visceral reality, and you can’t take your eyes off him.

Like Jacob the Jeweler, the real-life Bukharian Jewish jeweler to rap celebrities—“I went to Jacob an hour after I got my advance, I just wanted to shine,” Kanye West rhymes on “Touch the Sky”—Howard’s niche is selling to a clientele of black athletes and entertainers. The film’s plot is kicked into gear when Celtics basketball star Kevin Garnett (played by Kevin Garnett) is brought to the shop by an associate of Howard’s named Demany (a riveting Lakeith Stanfield) who works as a kind of celebrity procurer, steering big-name clients to the store in return for a cut of the sales. Garnett becomes entranced by the opal and the idea that it will bring him luck in the playoffs (the film is set around the 2012 NBA playoffs). He convinces a reluctant Howard to lend him the gem and offers his NBA championship ring as collateral. Howard, a degenerate gambler, immediately puts the ring in hock and uses the money to place a big bet on the game. The rest of the film careens between Howard’s frantic efforts to reclaim his opal and Garnett’s ring, while placing more bets and running from debt collectors, including his loan shark brother-in-law, played by Eric Bogosian, who gives a terrifying performance pretty much using only his eyes.

Gems is interested in the relationship between blacks and Jews, both for their affinities and in terms of power and exploitation. Howard loves basketball, and in the world of the film, loving basketball is a Jewish thing, as is, more generally, a love of all sorts of black entertainment that is both sincere and potentially exploitative. But Howard isn’t a malicious racist and he isn’t exactly powerful enough to exploit a millionaire like Garnett. And while he clearly has money, Howard has no class. He spends like a rapper whose first record just went gold, on blinged-out jewelry, Gucci belt buckles, and other status symbols that show one segment of society that he’s made it, and prove to another segment that he never will.

Lacking the desperate struggle to survive that drove his ancestors, Howard has accumulated only their worst qualities without any of the spiritual and communal substance that offered their lives purpose.

Within the global economy, Howard is clearly profiting from the sweat and blood of the African miners (even if the film tries, unconvincingly, to complicate this by revealing that Howard’s Ethopian contacts are fellow Jews of the Beta Israel tribe, without giving that background any substance). But Howard isn’t standing above someone like Garnett, who has vastly more money than he does. He’s selling something that Garnett wants, even if neither can explain what makes the object so desirable.

The other motor of the story is Howard’s romance with his much younger mistress, Julia (the actress Julia Fox), who works for him at the jewelry store and lives in his playboy apartment in the city. Their relationship is unexpectedly affecting for coming as something of a surprise—wait, the gorgeous and much younger Catholic girlfriend Howard wants to leave his wife for actually digs this glorified old used-car salesman? She’s attracted to the money and the hustle, it seems, but also charmed by Howard’s maniac charisma. The film never tries to explain it and the mystery makes the relationship feel real, like something that belongs to her that we can only glimpse.

It also sets up the film’s most aesthetically bravado sequence, a cinematic fugue that begins when Howard finds Julia doing coke in the bathroom of a nightclub with the new wave R&B singer, The Weeknd. It’s unclear to Howard and to us watching, how far she’s let things go trying to make a sale for the shop. Howard bursts into the bathroom. There’s a scuffle, some cursing and spitting, and Howard is escorted onto the street. He storms away screaming about having the club shut down. Julia is right behind him. It’s late at night as she follows him down the street toward the broad avenue where a cab waits. He’s done with her. She pleads and tries to explain, gives up, and then lashes back at him. He knew who she was when they met; that’s right he did. And the cab door slams shut—the camera pulls back to catch the action as they part ways and the score swells with electro-synth chamber music, like in a post-nouvelle vague French film of the 1980s. Spying on their little drama playing out against the backdrop of the mega city, the grand music coming from somewhere outside the frame, it’s like God’s own eye has been turned on these two holy losers.

***

Uncut Gems is really two films. It’s a smart, stylish thriller that takes the antiheroic common-man drama of the 1970s “New Hollywood’ auteurs and speeds it up to the pace and pitch of a chainsaw; and it’s a portentous allegory about Jewishness and capitalism.

The movie comes alive as a street-level portrait of a New York demimonde, the Diamond District, where Howard owns a cramped shop. The district is a one-block stretch of 47th Street between 5th Avenue and 6th Avenue cluttered with big outlets, small retail jewelry stores, appraisers, wholesalers, “buy and sell gold” establishments, street hawkers, and more than one kosher restaurant. It runs on a primitive form of capitalism in which the hidden volatility inherent in commodity value is revealed by the daily fluctuations in the prices of precious stones. Knowledge consists of more than just information in the gem trades. Expertise requires experience and tactile acumen, acquired from years of handling customers and handling stones. Who knows how long it can survive before Amazon eats it up and makes its workings invisible inside the cloud. But for now, the district holds onto an older culture with little interest in the high-minded self-imagining that other businesses use to disguise their profit motive.

Profit motive is in Howard’s blood, the story suggests. He’s the heir to millennia of Jewish traders, shopkeepers, shtetl burghers, rag peddlers, furriers, and car salesmen; cousin to all the Russian, Syrian, and Bukharian wannabe-Crazy Eddie Jews who have opened up cellphone stores in Brooklyn and Queens and just want to buy nice things, and then buy nicer things, and more of them. Lacking the desperate struggle to survive that drove his ancestors, Howard has accumulated only their worst qualities without any of the spiritual and communal substance that gave their lives purpose. He still shows up to the family Seder, upholding the Passover tradition like generations before him, but he can only go through the motions like a zombie, turning the central metaphor of Jewish life from a tale of longing and survival into a night of the living dead.

Howard’s compulsion to buy, sell, and acquire more by any means competes with his pathological drive to gamble. It’s not enough that he owns a business, has loyal employees, a big house in Queens, a nice car, and a beautiful wife, played with long-suffering contempt by Idina Menzel, who has given him a family. He wants everything else, too: the hot young Catholic girlfriend, the apartment in Manhattan, to be a winner, set free by the big score.

The psychology of “capitalist” and “gambler,” are superficially similar since both appear to be motivated by money, but they represent conflicting and irreconcilable urges. The best explanation I’ve ever heard of what motivates gambling addicts comes from comedian and Sandler pal, Norm Macdonald, in an appearance on the Howard Stern show. Explaining to Stern how, after going broke from gambling and then slowly making his money back, he gambled it all away a second time, Macdonald tells a story about the actor Omar Sharif. Sharif had made his own fortune but he was also a card player and in one epically bad run, lost $6 million at the tables; or so the story goes. With no more money left to wager, Sharif left the casino and walked into a coffee shop where he found that he had one dollar left in his pocket. At that moment he finally felt clean.

If compulsive gambling is really about what Norm Macdonald says it is, namely the buried desire to lose everything and feel the ecstasy of emptiness, then Sandler’s character is wagering his way out of the burden of being a Jew. He’s an arch-capitalist who is instinctively drawn to profit-seeking as a facet of his primal Jewishness, which is also the source of his self-hatred. There’s an element in Howard of “The Jew” as Orwell depicts him in Down and Out in Paris and London, meek yet puerile, “in a corner by himself … muzzle down in the plate … guiltily wolfing bacon.” And yet, partly because of the power of cinema to generate a sense of identification with anti-heroes, and partly because Sandler plays Howard without any groveling and buoyed by a naïve enthusiasm, you can’t help but empathize. Like Crazy Eddie Antar, he’s so over the top that you end up rooting for him without ever quite believing that he’s real.

Josh Safdie has argued that in its use of anti-Semitic stereotypes, the film is dramatizing the effects of their lineage. “What you see in Howard,” Safdie told an interviewer, “is the long delineation of stereotypes that were forced onto us in the Middle Ages, when the church was created, when Jews were not counted toward population, and their only way in, their only way of accruing status as an individual, as a person who was considered a human being, was through material consumption.” That ethic, once necessary for survival in the Middle Ages has stuck around and become perverse. “As assimilation has accrued, the foundation, the DNA of the strive has become kind of cartoonized in a weird way. What you’re seeing in the film is a parable. What are the ill effects of overcompensation?”

What I loved about Gems walking out of the theater is that the Safdies managed to take that most creatively exhausted and culturally overdetermined character, the New York Jew, and say something new about him. Gems’ hustlers are not the new-age New York Jews from Woody Allen and Seinfeld. Relative to the rest of the city, the Diamond District is overwhelmingly made up of immigrants, the Orthodox, and Hasids. By the cultural standards of the upper middle class, they are vulgar and backward, bounded by the parochialism of their religious or ethnic enclaves. They haven’t gotten the message that you can’t rise up without assimilating, and you can’t assimilate by trading in the unclean currencies of hard power. Instead of another class-flattering portrait of neurotics, the Safdie’s made a film about a fascinating corner of the world that hides in plain sight. As a social narrative, Gems is phenomenal.

But Howard the shopkeeper isn’t just a character, like a small-time Crazy Eddie. He’s supposed to be something more, and that’s where the film founders. It never occurred to me that Crazy Eddie had any bearing on the essence of Jewishness, or on the Jews as an historical people, any more than his downfall revealed the true essence of Syrian immigrants or of Brooklyn. Yet that is explicitly the claim that Uncut Gems is making for Howard Ratner. In the outsize iniquities of his persona, the film imagines a Jewish soul hollowed out by modernity and replaced by a parasitic capitalist meme that keeps reproducing until it takes over the host.

But who actually believes that? No one, really, including all those young authors of Marxist critiques trading notes in Brooklyn bars. A guy like Howard Ratner, in the larger scheme of things, is a cultural and commercial relic, utterly marginal to the integral operations of globalized capitalism.

So here’s my theory: By deploying the aura of political critique, the filmmakers essentially purchased an indulgence to use stereotypical tropes that have enormous, almost mystical power as storytelling tools, but would, in other contexts, have violated cultural taboos. The reason they used those stereotypes was not because the Safdies want to hurt Jews—the opposite, obviously, is true—but neither was it in order to make deeply felt political points about late capitalism. It’s insurance. A way to give audiences, Jewish and gentile alike, the thrill and psychological release of seeing repressed cultural phantasms about Jews blown up onto the big screen. That may seem like a political act in the current nervous atmosphere, but if the point of conjuring fears is just to provide a psychological vent, it’s only an ersatz version, like a polished glass knockoff, lacking the commitment of genuine politics and the courage of vision essential to great art.

In Gems, the Safdies made a film that is too wild to win any awards from the Hollywood establishment, yet too rule-bound to risk alienating critics by implicating them in its moral judgements. On the creative periphery of the professional-managerial class, consuming cultural critiques of late capitalist consumerism is a marker of status, far more expensive if you factor in the cost of college, but no more inherently righteous than wearing a gold chai necklace nestled in overly abundant chest hair.

Jacob Siegel is Senior Editor of News and The Scroll, Tablet’s daily afternoon news digest, which you can subscribe to here.