Unrepentant

Larry David, the antihero of HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm, is particular, a prig, and constantly aggrieved. But he’s fine with that—which is why, contrary to type, he’s not at all neurotic.

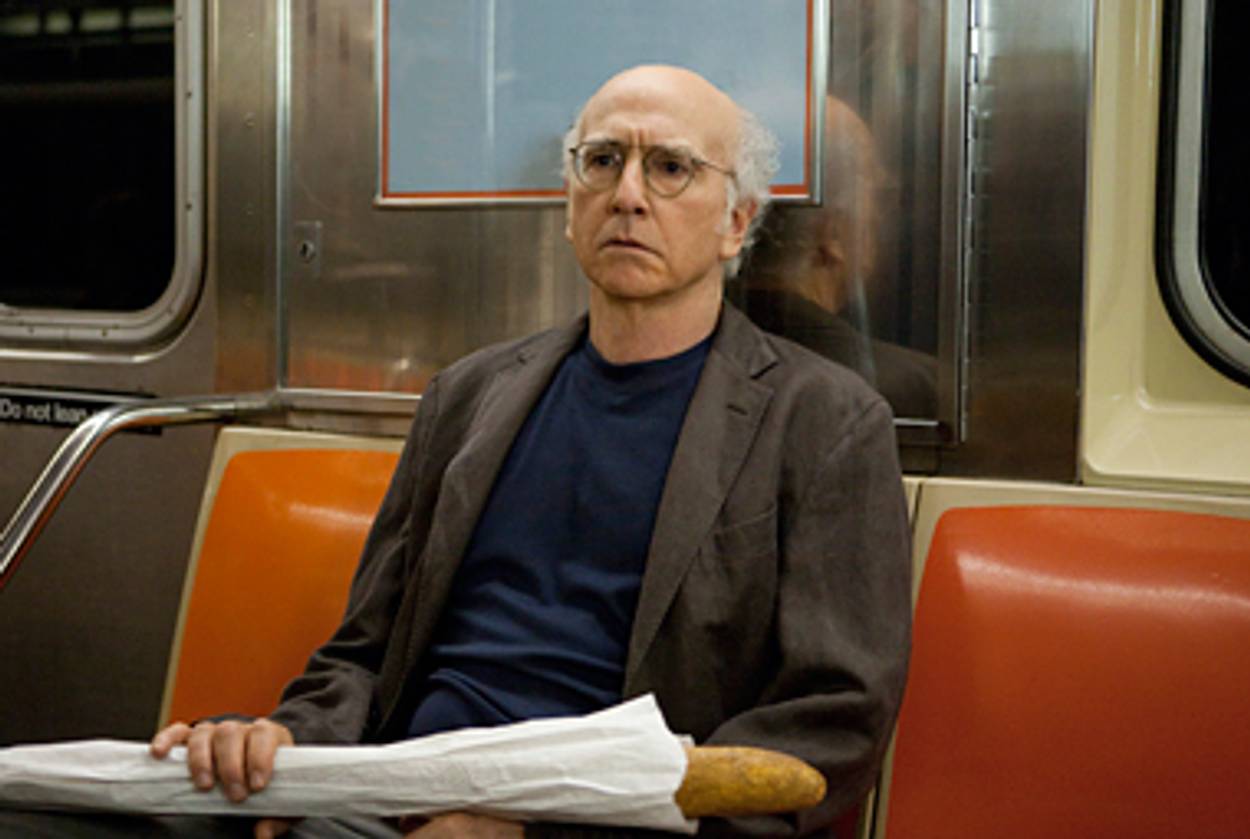

There are three adjectives that are often used to describe Larry David, the star and creator of Curb Your Enthusiasm, which recently premiered its eighth season after two excruciating, Curb-less years. One is “bespectacled,” which is fair enough. Another is “bald,” a signifier David’s television alter-ego regards as a traditionally oppressed tribal identity (spitting in biblical fury when the assimilationists among this imagined fraternity of the hairless attempt to “pass” under the camouflage of a baseball cap or, God forbid, a toupee). Finally, and most ubiquitously, he is “neurotic.”

“Larry David plays himself as bald, bespectacled neurotic,” the New York Times wrote in a review of the new season. “Larry David plays a neurotic fussbudget named Larry David,” the Washington Post said in 2010. “He’s officially an LA neurotic,” the New York Post recently bemoaned. Far be it for me to argue with writers for such august publications. But having said that: I don’t think any of these people actually know what “neurotic” means, other than a word you swap in when you think it’s impolite to say “Jew.”

I can’t speak to the inner tumult of the real Larry David, the writer and actor behind the bald, bespectacled mask. I’ve never met the man. (If I ever did, we either would circle each other silently in a moonlit forest clearing before gently pressing our foreheads together like unicorns performing a mating rite, or within five minutes each lie dead by the other’s hand.) Yet by any measure—and certainly compared to his Jewish comedic contemporaries—Larry David is a character remarkably free from internal conflict. Psychoanalytic theory holds that neurosis occurs when the different parts of the personality are at war with each other. Now think of Larry David: He has no internal conflicts; he’s difficult, but he’s content.

Not for him the unrelenting angst of Albert Brooks or the comically tattered sense of self-esteem of Richard Lewis (a frequent Curb Your Enthusiasm guest star). As for the Grand Emperor of Neurotics, Woody Allen (and David’s director in the 2009 film Whatever Works), the two men’s public personas could hardly be more different. Apart from the glasses, the Brooklyn accent, and their Jewishness, David is, in effect, the anti-Allen.

Skeptical? Consider, for a start, their attitudes toward women. A defining theme in Allen’s oeuvre, women are no more than an afterthought in David’s, and the latter gives his female stars far more interesting things to do. (Just think of Susie Essman‘s volcanically foulmouthed Susie Green.) David is no romantic; he wouldn’t have lasted five minutes with a whimsical naïve like Annie Hall. In the first episode of Curb’s latest season, David’s divorce from Cheryl is finalized; first, though, there is a possibility of reconciliation, which David characteristically bungles. Cheryl leaves and then David just cuts to his divorce lawyer, one year later. One can imagine Allen commemorating this event with a sentimental montage of happier times; Larry is more concerned with Dodgers tickets and whether his divorce lawyer is lying to him about being Jewish.

Nor does sex hold him in any particular thrall; in last Sunday’s episode, as Jeff, Leon, and Marty Funkhauser are rendered all but catatonic by the bodacious ta-tas on Richard Lewis’ burlesque-dancer girlfriend—Lewis, in true Allen fashion, can only bring himself to admit he admires her for her mind—Larry calmly slurps his drink and later matter-of-factly informs her that she has a mole on the underside of her right breast that she really ought to get checked out. In all realms sexual David is refreshingly un-creepy. In the world of Curb, Jeff and Susie’s teenage daughter, Sammy, is Larry’s antagonist; in the world of Allen’s films, she’d be a love interest.

Their relationships with technology are at odds as well; compare Allen’s famous war with machines to Larry’s primal rage at vacuum packaging. Allen blames himself for his difficulties. With Larry, it’s the package’s fault. For David, the conflict is always external, and this lack of introspection characterizes virtually all of his interpersonal actions.

When David refuses to add an additional tip for the servers at the country club, the problem isn’t his parsimony, it’s the server’s greed. He feels similarly in the right when he tries to rescind his order for Girl Scout cookies, or screams at the neighborhood kids for serving him subpar lemonade. Why should he allow himself to be taken advantage of? As far as Larry is concerned, his only problem is the unreasonableness of others. He might come off like kind of an asshole, but that’s your problem, not his. He’s a self-actualized asshole.

It’s tempting to ascribe David’s blind unconcern for the feelings and good opinion of others on his immense fortune, which is alluded to, if rarely explicitly stated—if I had half a billion dollars, I probably wouldn’t care what anyone thought of me either. But Larry seems utterly unimpressed by the trappings of wealth—he still buys his pants at Banana Republic, for God’s sake—and as such, I propose his bizarre self-confidence comes from another, deeper source: Virtually alone among his peers, Larry David has absolutely no ambivalence about being a Jew.

From his disgust at Cheryl’s enormous Christmas tree, to the glee with which he hangs a mezuzah with his father-in-law’s special Christ Nail, to his inadvertent rescue of a Jewish man from a mildly coerced baptism, David’s outlook is essentially tribal. To him, a Jew trying to pass as a gentile is as ridiculous as a bald man in a toupee. David’s comic pose is less that of the anxious assimilationist eager to fit in than that of the clueless greenhorn making his way in a world to which he’s not sure he cares to belong.

Or perhaps he’s even more atavistic than that. Neurosis is often defined as a focus on behavioral minutiae that can border on the obsessive-compulsive, but Larry’s many preoccupations, from the unwritten laws of dry-cleaning, to the proper way to treat chauffeurs, gardeners, and other menial laborers, to the irrevocable uncleanness of certain objects (pens that have seen the inside of Jason Alexander’s ears, $50 bills laced with Funkhauser’s foot sweat) recall another endless litany of unbending edicts: the Book of Leviticus. Larry David isn’t a neurotic; he’s just demanding. Like the God of the Hebrews. He can be kind of an asshole, too.

Rachel Shukert, a Tablet Magazine columnist on pop culture, is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great. Starstruck, the first in a series of three novels, is new from Random House. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.

Rachel Shukert is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great,and the novel Starstruck. She is the creator of the Netflix show The Baby-Sitters Club, and a writer on such series as GLOW and Supergirl. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.