The Velvet Underground & Todd Haynes

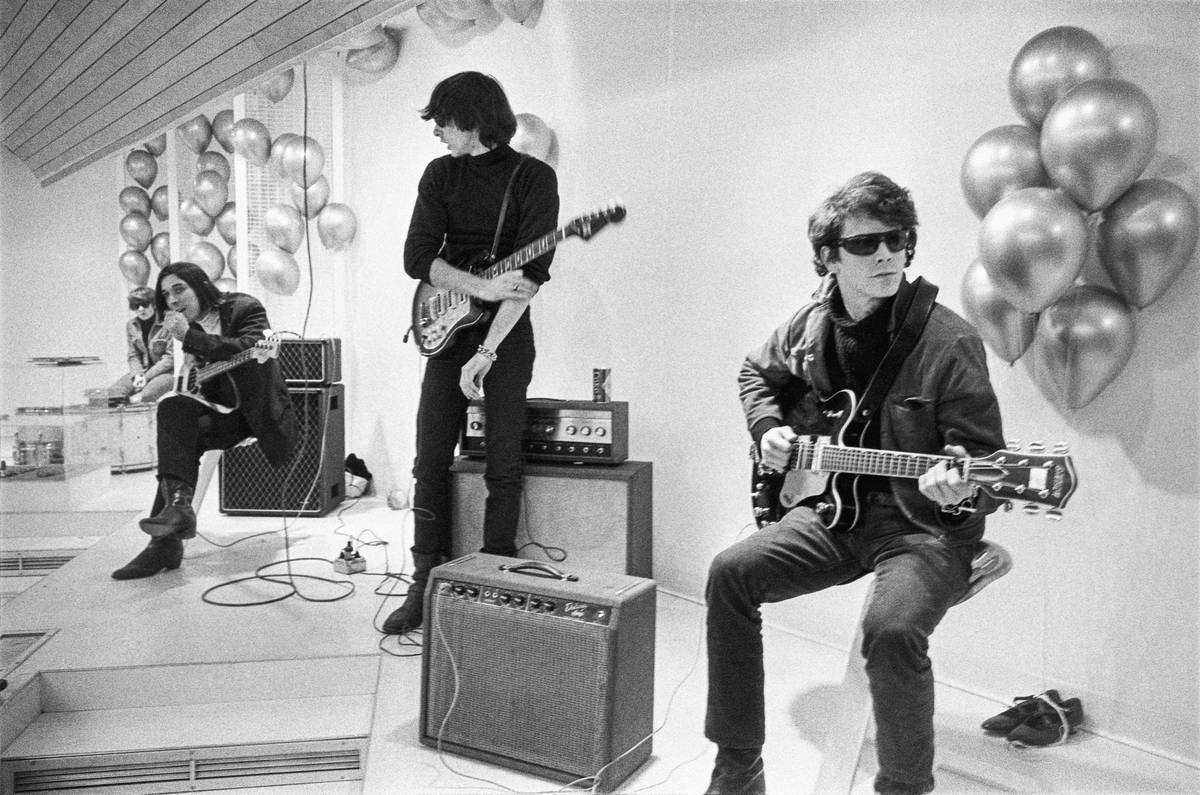

The filmmaker’s latest is as much about ’60s New York as it is about the iconic band, whose debut album will celebrate its 55th anniversary Saturday

“It is said that nowhere in the world are so many people crowded together on a square mile as here.” So Jacob Riis wrote of the lower Manhattan neighborhood he called “Jewtown,” noting that “the average five-story tenement adds a story or two to its stature in Ludlow Street.”

Rather than by extra stories, the particular stature of 56 Ludlow, a dumbbell-shaped Old Law tenement built just down from Grand Street in 1900, should be insured by a plaque: Cradle of the Velvet Underground. Until then, however, Todd Haynes’ documentary portrait, The Velvet Underground—a movie as much about New York in the ’60s as it is about the band—will do.

Thanks to the punk explosion of the 1970s, the East Village has lots of rock ’n’ roll landmarks—there’s even a street named for Joey Ramone. The old Lower East Side, not so many, with the exception of the tenement on long-since demapped Cannon Street where Naphtali “Tuli” Kupferberg—co-founder of the Fugs, the original East Village band—was born 99 year ago into a Yiddish-speaking family. Traces remain of the Rivington Street candy store owned by the parents of Genya Raven (born Genyusha Zelkovicz in Lodz in 1940), a child survivor of the Holocaust who grew up in the deep Lower East Side and became the lead singer for the all-female band Goldie and the Gingerbreads and later Ten Wheel Drive.

Although barely a memory, Goldie and the Gingerbreads—four girls in stiletto heels and gold lamé tights—were the first rock band to enter, however briefly, Andy Warhol’s orbit. It was in late 1964, around the time when they played a gig at a legendary birthday party for Warhol’s first superstar, Baby Jane Holzer, that many blocks downtown, the Velvets, as they were commonly called, came together in a cold-water flat at 56 Ludlow.

The old Lower East Side was one sort of melting pot; the neighborhood epitomized by 56 Ludlow was another. Haynes uses a clip of underground movie impresario Jonas Mekas, to whom his movie is dedicated, to introduce the New York of the ’50s and ’60s as the “place to which artists escaped.” Inhabitants of this slum tenement, whose landlord packed a gun while collecting the impossibly cheap rent, included underground filmmaker Jack Smith who had filmed his notorious Flaming Creatures on the roof of the nearby Windsor Theater and his star Mario Montez, as well as the three members of hypnotic drone-master LaMonte Young’s avant-garde Theater of Eternal Music—Angus Maclise, Tony Conrad, and John Cale—who would form the nucleus of the VU. The Italian Jewish poet madman Piero Heliczer was also around and by early 1965, so was Lewis Alan Reed, an aspiring songwriter-slash-rocker and the son of a Brooklyn tax accountant who changed his name from Rabinowitz. (Would Lou have had the same career if he hadn’t?)

Conrad moved out of 56 Ludlow and Reed, who had been living with his parents in suburban Freeport, Long Island, moved in. Before long he and Cale were doing drugs and setting Reed’s poems, including “Heroin” and “Venus in Furs” to music. Reed, Cale learned, was not just a committed rocker but a writer who, during his years at Syracuse University, had been mentored by the Partisan Review poet Delmore Schwartz and influenced by the Beats. (No less than Bob Dylan, he aspired to be a rock ’n’ roll Allen Ginsberg.)

Known as the Falling Spikes (and briefly, the Warlocks), the future Velvet Underground provided loud drone music for various mixed-media performances staged at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in the East Village and appeared in Heliczer’s 8 mm opus Venus in Furs (described as a movie “where a nun and a nurse go to hell for their sinful life in St. Vincent’s Hospital”), which was shot in his loft at 450 Grand Street. The times were such that the shoot was simultaneously filmed by a TV camera crew for a news item on underground movies. Appearing shirtless and with painted faces, Cale, Morrison, and Reed performed “Heroin,” with Heliczer joining in on the saxophone. Moe Tucker, now part of the band, wore a bridal gown and a mask while underground networker supreme Barbara Rubin appears as the nun.

Rubin, a filmmaker who knew virtually everyone in the downtown scene, was the band’s angel. She hooked them up with their first manager, the hip journalist Al Aronowitz (for whom she babysat), as well as their second: Andy Warhol. Aronowitz secured the band a gig at a New Jersey high school, followed by a residency at the Village’s most venerable tourist trap, the Goth-themed Café Bizarre where six nights a week, they played for nonplussed audiences in a largely empty basement cavern. Rubin brought her friends—including Warhol and his entourage—and the rest is history. On Jan. 3, 1965, the band made their way uptown to the Warhol Factory on East 47th Street to jam with Andy’s new Girl of the Year, the 28-year-old German actress Christa Päffgen who, recently arrived in New York, now called herself Nico.

Two weeks later, Warhol introduced his band to a select public, namely the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry’s annual dinner. It was a freak-out for the ages. After the Velvets serenaded the society, playing at top volume against a background of projected films, Rubin ruined their dessert, blasting the shrinks with a hand-held spotlight while shouting impertinent questions regarding their sexual practices and sex organs. (The New York Herald Tribune headlined their review of the performance “Shock Treatment for Psychiatrists.”)

In the spring of 1966, a more elaborate version of the act—now known as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable—took up residence upstairs of the former Polish National Home on St. Marks Place, familiarly known as the Dom. There, the High Sixties, or at least the disco nightclub, was born in a visual frenzy of strobe lights. A battery of 16 mm and slide projectors covered the walls, the ceiling, and the band with Warhol’s movies.

The Velvets themselves played at an ear-shattering, feedback-inducing volume with occasional Nico breaks. Warhol superstars, which is to say, resident hip kids, Gerard Malanga and Mary Woronov (daughter of a Brooklyn doctor) mimed S&M to the beat as the mind-blown multitudes came to dance.

Todd Haynes, arguably the nation’s leading independent filmmaker, is also a careerlong student of pop. Haynes made his debut in 1987 with Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, shot on Super 8 with a cast of Barbie dolls. Subsequent features included The Velvet Goldmine, a fictional account of a glam rocker’s rise and fall, and most audaciously I’m Not There, a fictional biopic with five different actors playing Bob Dylan. (He’s currently preparing a Peggy Lee biopic, starring Michelle Williams.)

The Velvet Underground is less a conventional documentary than a ’60s film made today—a movie that uses numerous film quotations and dated avant-garde techniques, as well as rapid-fire editing to evoke a specific period. Haynes frequently splits the screen and multiplies the image, annotating the testimony of talking heads, while sampling underground movies by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, Harry Smith, Ken Jacobs, Piero Heliczer, and Barbara Rubin.

News footage flashes by, showing early ’60s gay bars and coffee houses. Haynes sneaks in a bit of Dylan footage but not everything is so familiar: It’s extraordinary to see John Cage, the most radical composer in America, appearing as a guest on the popular game show What’s My Line? The montage is often brilliant, as with one scene’s juxtaposition of the Cage disciple Cale purposefully destroying a piano alongside a group of college frat boys pulling the same prank.

The visual onslaught serves as a reminder that initially, in their greatest period, the Velvets performed amid a barrage of projected images in performances designed for sensory overload. The same strategy, albeit less aggressive, has served two complementary documentaries on the period. Both Chuck Smith’s Barbara Rubin and the Exploding New York Underground (2019) and Thérèse Heliczer’s portrait of Piero Heliczer’s The Invisible Father (2020), use similar means (and sometimes identical footage, including the performance in Heliczer’s loft) to explore the same milieu.

As much as it is a portrait of the Velvet Underground, however, Haynes’ documentary is a tribute to Andy Warhol at a time when the artist personified the New York avant-pop. Factory footage is ubiquitous, particularly the three-minute static portraits that Warhol called “screen tests.” Haynes introduces Lou Reed and John Cale, among others, through their tests—at one point creating a delirious Hollywood Squares effect by dividing the screen into 12 simultaneous screen tests.

Without belaboring the point, The Velvet Underground also makes the case for Warhol’s enduring significance. Film critic Amy Taubin who had, as a young woman, been part of the underground scene, points out the analogies between Warhol’s slow, durational cinema, and La Monte Young’s long sustained tones, leaving the viewer to appreciate the original Velvet Underground as the rock ’n’ roll synthesis of these two artists.

Cale’s take on Warhol is illuminating as well. He recalls admiring Warhol’s work ethic and business acumen. Rather than a festival of decadence, the Factory was, he says, “all commerce.” Indeed, Warhol’s insistence that the Velvets incorporate the Nordic ice queen Nico and her sepulchral voice into their act, if not their band, was a brilliant bit of packaging. So too, was the peelable banana on The Velvet Underground and Nico, the first and by far the best Velvet Underground LP.

No mention is made of the possible influence of the ’60s greatest musical avant-garde, namely free jazz, other than that it was in the air (not least on the Lower East Side). At one point, Cale remarks that “the way we could give Bob Dylan a run for his money was to go on stage and improvise every night.” It’s worth noting that the engineer Tom Wilson, who produced three early Dylan LPs, also produced several Sun Ra albums, as well as (uncredited) the Velvets’ debut.

In some ways, the Velvets peaked early. Leaving the safety of St. Marks Place, they went on tour. The band was too dark for LA and bombed in San Francisco—hippies hated them and the feeling was mutual—although they did find a fanbase in Boston. (Interestingly, their local popularity overlapped with that of the Grateful Dead, another band that broke out performing amid psychedelic light shows and, like the Velvet Underground, was once named the Warlocks.) For future Modern Lovers founder Jonathan Richman, who remembers trading his Fugs album for The Velvet Underground and Nico and attending over 50 performances, the Velvets were transformative—they “hypnotized the audience.”

That was Boston. Back in New York, Nico went solo and shortly after, Reed fired Warhol as manager. The Velvets’ second LP, White Light/White Heat, was aggressively cranked-up and speedy, fueled by amphetamine and recorded off the cuff. After the album was released in January 1968 (and about three-quarters of the way through Haynes’ two-hour film), Reed essentially kicked Cale out of the band. The experimental period was over. Adding a fourth, bassist Doug Yule, the Velvets hung together for another 18 months as a more conventional rock band.

The Velvets played their last gig during the summer of 1970 at the preeminent avant-garde watering hole (and Warhol Factory commissary), Max’s Kansas City. To judge from The Velvet Underground, the residency was a cold latke if not an out and out disaster. Reed quit the band on the way out the door to fulfill his destiny as a rock ’n’ roll animal.

Still, even writing headbanging odes to that “fine, fine music,” Reed kept an experimental edge. After years of not speaking, he and Cale reconnected at Warhol’s funeral in 1987, remaining in touch long enough to create and perform Songs for Drella, a musical suite dedicated to their spiritual producer. Released in 1990, when the guys were pushing 50, the album has a certain quality of their youthful jam sessions.

As for Ludlow Street, where it all began, the last time I checked the monthly rent for a unit in 56 was almost $3,000—nearly 100 times what it cost in 1964.

The Velvet Underground streams via Apple TV+. The Invisible Father is available from Apple TV as is Barbara Rubin and the Exploding Sixties (along with other sources).

J. Hoberman was the longtime Village Voice film critic. He is the author, co-author, or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.