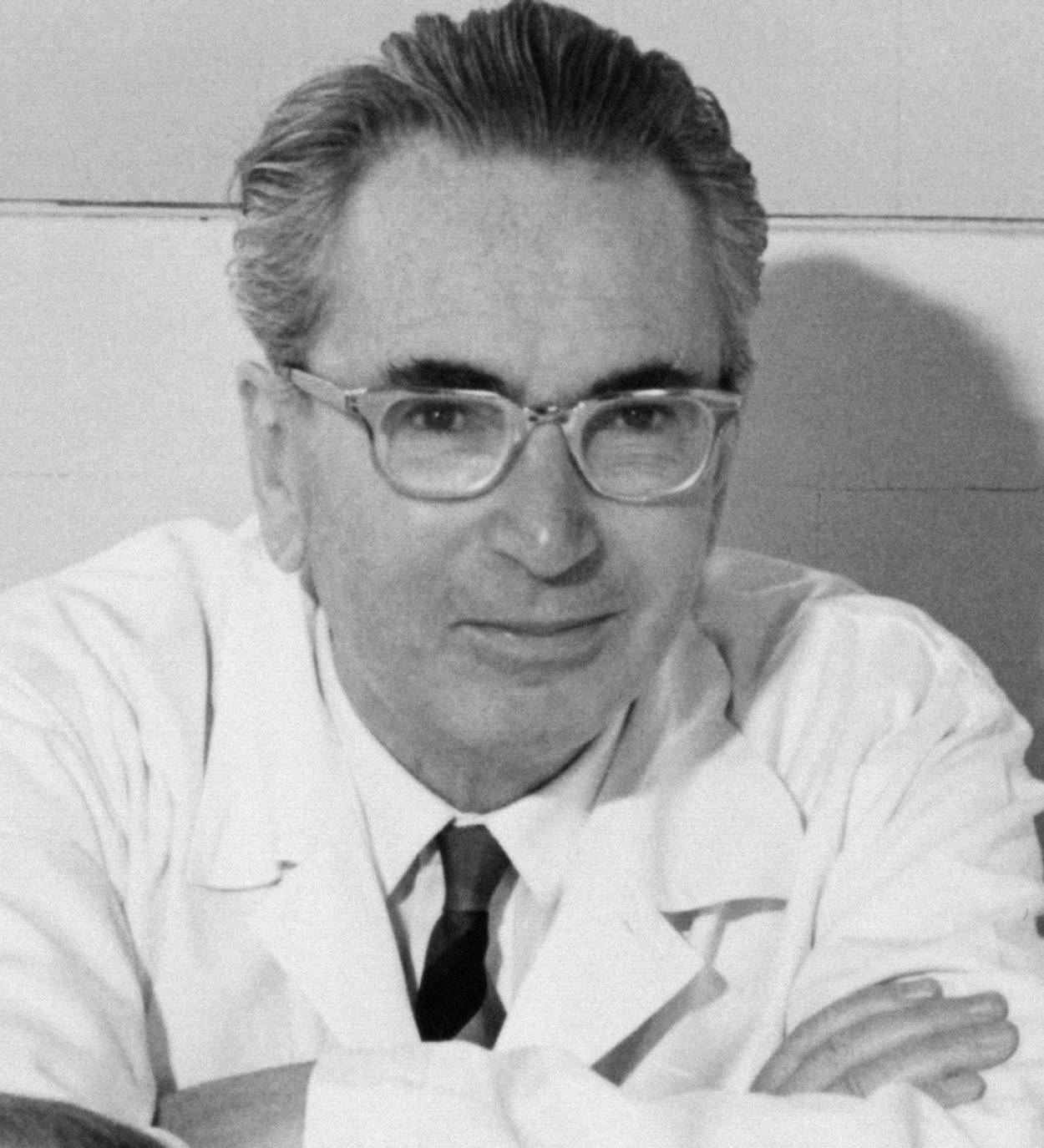

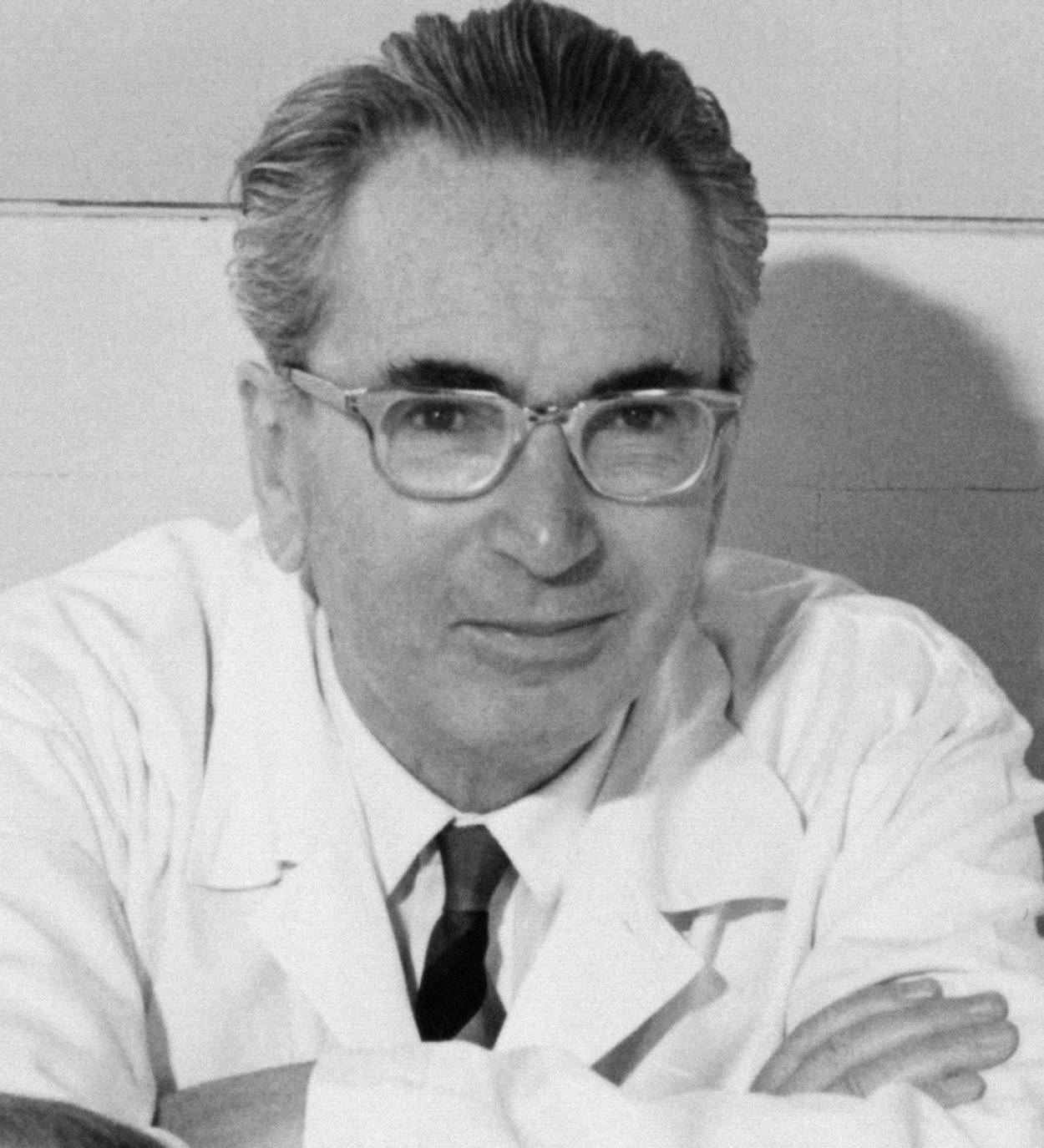

The Life of Viktor Frankl

An exchange about the survivor and psychotherapist—and the ‘lessons’ of the Holocaust

In September 2020 Tablet published your essay titled “The Lie of Viktor Frankl.” It has certainly made a stir in my intellectual circle. I am writing in the name of several friends and colleagues, with whom I have discussed your article at length; their ideas are reflected in my comments. (I am particularly grateful to professor Golda Akhiezer in Jerusalem and Uri Blank in Boston.) We think that your arguments and insinuations about Frankl are grossly flawed, if craftily presented. Beyond the effort to disrepute Frankl as a person, you seek to discredit his contribution of transmuting suffering into a life-affirming journey to discover personal meaning.

You strike hard by opening your essay with a story of Frankl’s 1941 “medical experiments” on his Jewish patients who committed suicide in the Nazi-ruled Vienna. The nature of Frankl’s brain treatments is a gray area—and you know better than to rely on a single source, Timothy Pyttel’s much-criticized (and much-revised) research. Still, you present Frankl’s desperate effort to bring to life the clinically dead patients as if he committed Nazi-like medical atrocities. Your cynicism is quite misplaced when you scoff at Frankl’s motives for seeking to prevent suicides—purportedly so that the Jews would have a chance to bear suffering with dignity. Frankl had yet to spend three years in the Nazi camps to develop his beliefs.

“What Frankl failed to see was that Austrian Jews were making a political statement by killing themselves,” you underpin Pytell’s claim that their “Masada tactic” was an act of protest. Perhaps it was for very—very!—few, but the majority took their own lives “at the rate of about 10 a day ... in the hope of escaping their Nazi tormentors,” as you point out correctly. An expert in suicide prevention, Frankl treated suicidal Jews, terrorized, terrified, and driven to despair.

“In November 1941 Frankl received a visa to emigrate to the United State from Austria, but he decided to stay” because, you affirm, he “clung to the hope that Jews could have a life worth living in a Europe ruled by the Nazis.” However, like anyone familiar with Frankl’s life, you know the real story. This was not the place or the time for detached contemplation of European destiny. Frankl agonized, unable to decide whether he could leave his family in mortal danger until he saw a fragment of the Torah scroll from the burned central synagogue in Vienna. It contained the commandment to honor one’s parents. Frankl received his answer and stayed.

Your title is brazen, if befitting your essay, which portrays Frankl as a fake. One must have weighty reasons to accuse someone of lying, wouldn’t you agree? You say that Frankl spent almost all his imprisonment not in Auschwitz but in other Nazi camps; yet, Auschwitz is often mentioned in his memoirs. Perhaps Frankl starved, and froze, and slave-labored in Dachau longer than he did in Auschwitz; does this reduce the value of his story? Possibly he referred to Auschwitz, employing a familiar symbol of the Holocaust. But he does not mislead his readers. You may have overlooked his statement at the onset of Man’s Search for Meaning: “Most of the events described here did not take place in the large and famous camps, but in the small ones ...”

You claim that the “use of the Shoah to provide life lessons for the rest of us remains questionable.” Frankl did not “use” the Holocaust; he lived it. Everything he had to say about it was intimate and personal. And what is “questionable” about revealing personal insight deriving from dreadful experiences? Many, if not most Holocaust survivors choose to keep silent, rather than relive pain and death. Any effort to impart their bloodstained wisdom is generosity. Generously, Frankl shares his innermost discovery of meaningful suffering because it may be therapeutic for “people who are prone to despair.” He did not write a detached study about anguish; he was still living the nightmare and mourning the loss of almost everyone he loved during the nine days of sorrow in 1945, when he spilled out his book, composed with tears.

You accuse Frankl of “wishful thinking,” which “turns a devastating reality into a spiritual triumph.” You call it “morally dubious, since the truly agonizing and destructive effects of the Shoah on its victims are whitewashed away.” Nice of you not to accuse Frankl of denying the Holocaust. In fact, morally dubious is to forbid the survivor his hard-earned grasp of a spiritual victory over his torturers. It is also intellectually flawed to proclaim his empowering experience to be deceptive because it does not fit a perception of how it had to be—from the outside. The gist of misunderstanding is that for you the camps are an object for evaluation, a horror story, whereas Frankl was its subject, who nearly perished and lost his parents, brother, and pregnant wife. You and Frankl are looking at the same thing from different vantage points; nothing wrong with it. But a judgment of survivor’s reality from the outside is presumptuous and invalid.

Frankl’s “central idea was to guide his patients toward finding meaning, the most necessary thing in life.” But, you say, instead of simply helping them “adjust to their situations,” he would “show why life is worth living.” On the contrary, Frankl accentuated that he was not telling others why life is worth living—only that in order to make it worth living they need to render it meaningful. Frankl does not supply the meanings; he helps his patients find their own.

“They would become enlightened, rather than merely more ready to make their peace with common unhappiness,” necessitated, you remind us, by “the myriad possibilities for human disaster.” You dismiss as “starry-eyed idealism” Frankl’s endeavor to reject victimhood and to transform raw misery into spiritual means for an inspired life. Investing life with personal meaning empowers. Having discovered this to be true for himself even in the camps, Frankl empowered others, though, in your eyes, he was a “clichémonger, given to mouthing platitudes.”

By contrast, you like Primo Levi, who authored “the most necessary of all books about the Shoah,” as you state elsewhere. After almost a year in Auschwitz, Levi’s primary goal is to show “what this place of mass death does to its inhabitants,” and “how prisoners use one another to survive.” Levi experienced imprisonment as a plunge into an abyss, from where one could not escape even in thought—ever. Elie Wiesel said that recurrently depressed “Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years later,” after hurling down several flights of stairs in a likely suicide.

Frankl certainly did not avoid many other “painful cases of Holocaust survivors who were unable to reconcile themselves to their past torment.” He acknowledges that depersonalization, physical and mental exhaustion, bitterness, and loneliness amid the devastating indifference to horrors of the Shoah caused him and other former prisoners to feel “like creeping into a hole and neither hearing nor seeing human beings anymore.” Nonetheless, the last pages of his memoirs are dedicated to recovery. Frankl traces the first step toward “becoming a human being” again to a walk in the flowering meadows, when—alone between the wide earth and sky—he quotes the psalmist time and again: “I called to the Lord from my narrow prison and he answered me in the freedom of space.” You intimate that “bringing God onstage” is bogus—so it must appear when you are watching the show from afar. Yet, for a terrorized and petrified shadow of a man, it is nothing less than a miracle suddenly to know “that, after all he has suffered, there is nothing he need fear any more—except his God.”

“Man is that being who has invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who has entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord’s Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips,” Frankl recaps. “By citing the Christian prayer before the Jewish one, Frankl redefines the Holocaust as more than merely a Jewish catastrophe,” you complain. The Shoah is indeed not merely a Jewish catastrophe: The fact that 6 million Jews were slain across the continent—often before the Nazis got around to give the order—indicates the ruin of the two-millennia-old Christian Europe. Poland is no longer Poland without its 3 million Jews. Yet, so eager you are to “cancel” Frankl—to employ the term now in vogue—you miss that his purpose is to reiterate the main message: Even on his way to the gas chamber one is free to choose his attitude. Exercise of this freedom affirms the sanctity of man, made in God’s image.

For the “practical-minded Levi,” Jewishness was “like having a spare wheel, or an extra gear.” You find this to be “a lovely image” and appreciate his memoirs’ opening with redrafted Shema prayer to be “an indelible curse” upon anyone negligent of the Holocaust. One cannot help but wonder how you can be so deferential to the idea of the Shoah and at the same time so dismissive of its survivor, with whom you do not share beliefs. Conversely, veneration of the Holocaust memory in Levi’s frivolous employ of Judaism you embrace as “holy blasphemy.”

Frankl did precisely the opposite, worshipping God in and by way of the Shoah. He revealed the divine image in the concentration camp—the place engineered specifically to purge the human being of the tselem Elokim. It is hard to think of any more meaningful kidush a’Shem.

Anna Geifman, in her letter, objects to the incendiary title of my review: “The Lie of Viktor Frankl.” The title was in fact supplied by my editors, not me, as is usual in journalism. But it is justifiable, on two levels. Viktor Frankl lied about the details of his wartime experience, and he lied about the significance of the Shoah, by claiming that it demonstrated our need for an optimistic attitude toward suffering. Frankl was a victim of the Jewish catastrophe inflicted by the Nazis, and, as I make clear in my piece, he endured unimaginable horrors. But this does not mean that we must draw a veil over the facts of his life, as Geifman seems to wish.

In “The Lie of Viktor Frankl” I rely on Timothy Pytell’s scrupulous 2015 biography of Frankl. Geifman claims that Pytell’s work is “disputed and revised.” Pytell did indeed revise his biography of Frankl between its original German publication and its appearance in English 10 years later. I have worked from the revised English-language book, which, Pytell notes, was strengthened by a response from Alexander Batthyány, the director of the Viktor Frankl Archive. The revisions Pytell made concerned matters of tone and emphasis, not historical fact. In any case, I have not even read the earlier German publication. The details I cite from Pytell are heavily documented, and have not been questioned by any scholar. Pytell’s biography is not an attack on Frankl, but an effort to give a full portrait of the man, including aspects that have been sidestepped by Frankl’s disciples: his wartime work with suicidal Jewish patients, his postwar defense of his mentor, Nazi party member Otto Pötzl (including the dubious claim that he and Pötzl had sabotaged euthanasia efforts), his late-in-life association with right-wing Austrian politicians like Jörg Haider, and his defense of Kurt Waldheim.

Does Geifman dispute the fact that Frankl repeatedly injected amphetamines into the skulls of suicidal Jewish patients, an operation which led to the agonizing deaths of these patients? As Geifman must know, Frankl himself admitted that he had done this, though not until many years later, when pressed by an interviewer. Frankl conceded that the experiments seemed “Nazi-esque” and added, “that was the atmosphere of the time” (the Nazis in fact supported the experiments, since they had “possible wartime use”). In the autobiography he wrote in his last years, Frankl called these operations “heroic efforts.”

The experimental brain operations are not mentioned in Frankl’s official biography, When Life Calls Out to Us, by the Frankl disciple Haddon Klingberg, though Klingberg knew about them. This suppression alone suggests the whitewashing practiced by Frankl’s acolytes. There are other instances. Klingberg writes that when Frankl repeatedly spoke of “the three years he spent in Auschwitz and Dachau” he committed a trivial distortion, since “he used these names as the ones his audience likely would recognize.” I maintain that the distortion is considerable. Frankl only spent three days in Auschwitz, as Pytell discovered when he examined train records. But he routinely implied, in Man’s Search for Meaning and elsewhere, that he was in Auschwitz for months, if not years.

Frankl was not a collaborator; he was a victim of the Shoah. But this does not entail that he should be immune to criticism. Nor is it the case, as Geifman claims, that survivors of the Holocaust and those born later are separated by a gulf that cannot be bridged. We judge everyone caught up in history, and let us hope that we judge sympathetically, especially in difficult cases. Frankl was in some ways a heroic personage. He was not a saint, however. He was more interesting than most saints, far more interesting than his simplistic, feel-good version of psychotherapy would lead one to believe.

I’m not sure why Geifman brings up my Tablet essay on Primo Levi. Levi’s attitude toward his own Jewishness is not to the point; neither is Frankl’s. What does matter, though, is historical truth. On every page of Levi’s work the reader recognizes the reality that under Hitler Jews were murdered because they were Jews. Frankl obscures this fact. In his wish to present the death camps as a universal experience, he scarcely mentions Jewishness: only twice, by my count, in Man’s Search for Meaning. When Frankl says that victims entering the gas chambers recited the Our Father or the Shema Yisrael, mentioning the Our Father first, he does so for a reason: to imply that the Holocaust was not first and foremost a Jewish tragedy. With this small choice of words, he commits a grave distortion. As Frankl surely knew (how could he not?), though both non-Jews and converts died in Auschwitz’s gas chambers, they were vastly outnumbered by Jews who had not converted to Christianity.

Geifman takes me, correctly, to be endorsing Levi’s sense that the Shoah is a permanent wound in human history. This does not mean I believe that survivors should feel bound to remain wretched, refusing life and happiness for the sake of the dead. Mistaking my point, she attributes to me this ghastly misanthropic lesson. I say something very different: that many survivors were not able to turn their experience into a spur to strength and happiness as Frankl thought they should have. It is certainly true that some who lived through the death camps felt themselves to be stronger because of what they had endured, and more appreciative of life. But to reduce the Shoah to this lesson is to miss the sheer depth of the disaster, and therefore to falsify history.

Anna Geifman is Senior Researcher at Department of Political Studies, Bar Ilan University, Israel and Professor of History (Emerita), Department of History, Boston University. She is the author of Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894-1917; Entangled in Terror: The Azef Affair and the Russian Revolution; and numerous articles and book chapters. Her most recent book is Death Orders: The Vanguard of Modern Terrorism in Revolutionary Russia.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.