The Lie of Viktor Frankl

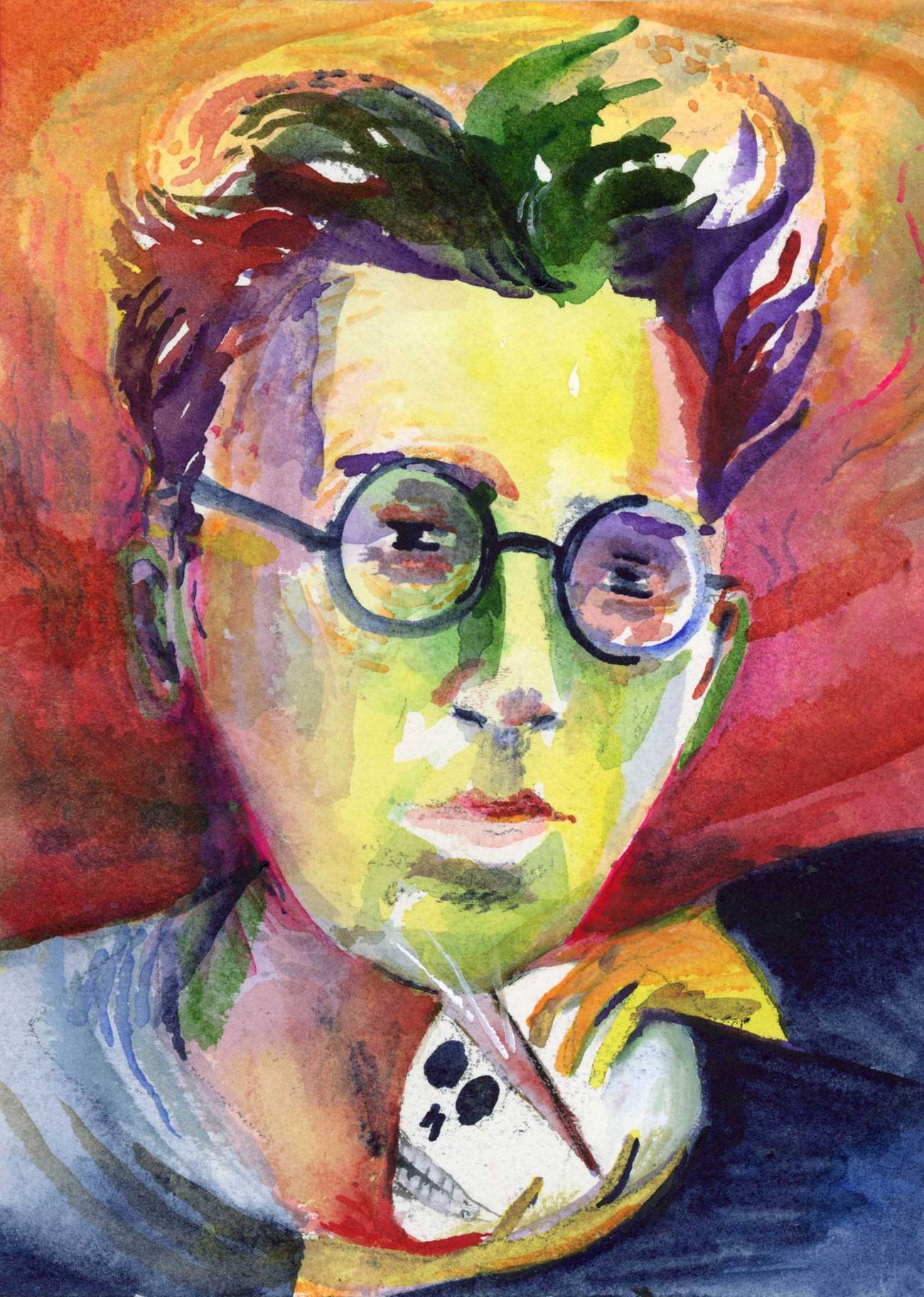

The author of the strangely misleading ‘Man’s Search for Meaning,’ repackaged as a psychotropic New Age guru, in the newly translated ‘Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything’

In 1941 Dr. Viktor Frankl was director of neurology at the Rothschild Hospital for Jews in Vienna. Austrian Jews were killing themselves at the rate of about 10 a day, and Frankl was determined to save them. Frankl tried to bring the suicidal patients back by injecting them with amphetamines, but it didn’t work.

And so, Frankl bored holes in the skulls of his Jewish patients, who had taken overdoses of pills in the hope of escaping their Nazi tormentors, and jolted their brains with Pervitin, an amphetamine popular in the Third Reich.

The suicidal patients revived, but only for 24 hours. One wonders what agonies they went through in their last day of life, with Frankl’s amphetamines coursing through their trepanned heads.

Frankl had next to no experience with brain surgery, though he routinely performed lobotomies. He had taught himself the surgery by reading the renowned brain surgeon Walter Dandy, but he missed Dandy’s warning that there was no drug “sufficiently harmless to justify its insertion into the central nervous system.”

Frankl confessed his shocking experiments only many decades later, long after he had become celebrated as a healer and sage for his book Man’s Search for Meaning (1946; first American edition, 1959). In that book Frankl wrote, “When a man finds that it is his destiny to suffer, he will have to accept his suffering as his task; his single and unique task. … His unique opportunity lies in the way in which he bears his burden.” The suicidal Jews had not borne their burden properly. If they lived they could still stake a claim to their suffering as a “unique opportunity,” Frankl believed.

What Frankl failed to see was that Austrian Jews were making a political statement by killing themselves, sometimes at the Gestapo’s deportation office. As Frankl’s biographer Timothy Pytell points out, their “Masada tactic” was an act of protest.

The Nazis in fact shared Frankl’s goal of preventing Jews from killing themselves, since they had decreed Jewish suicide to be “illegal.” Jews belonged to the Reich, to be disposed of as the Germans saw fit.

Frankl had a different motive. He clung to the hope that Jews could have a life worth living in a Europe ruled by the Nazis. Even after the war began, Frankl stubbornly refused to believe that Hitler’s regime was a death sentence for Jews like him. In November 1941 Frankl received a visa to emigrate to the United States from Austria, but he decided to stay: He was about to marry Tilly Gosser, a nurse at the Rothschild Hospital. His parents, along with his patients, were close by in Vienna. He could not imagine being a well-to-do Jewish doctor in Manhattan, he wrote after the war, at the cost of abandoning the people he loved.

An expert mountain climber, Frankl said once that for him the “three breathtaking things” were “a first ascent, gambling at a casino, and a brain operation.” In 1942 he hid his yellow star so that he could climb and breathe the free air of the Alps. But later that year the Nazis deported Frankl, his wife, and his parents to Theresienstadt. His father died there. Frankl’s mother was murdered in Auschwitz, and his wife, Tilly, died near the end of the war in Bergen-Belsen.

Frankl’s suffering was unimaginable. As Pytell reminds us, he was an innocent victim, not a collaborator with the Nazis. But his use of the Shoah to provide life lessons for the rest of us remains questionable, as Pytell and Holocaust scholar Lawrence Langer point out.

Frankl insisted that surviving a Nazi slave labor camp could strengthen the human spirit. Such positive thinking has always been popular, especially in America, where Man’s Search for Meaning is a perennial bestseller and books by and about Frankl continue to appear regularly. Beacon Press has just published, for the first time in English, the lectures that Frankl gave in Vienna in 1946, under the title Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything. For a book produced in the rubble of postwar Vienna, it has a conspicuously New Age aura.

Yes to Life, like Man’s Search for Meaning, markets Frankl’s logotherapy, the brand of treatment which he proudly billed as the “third Viennese school,” following Freud and Alfred Adler, who invented the inferiority complex. Frankl’s central idea was to guide his patients toward finding meaning, the most necessary thing in life. Instead of simply helping patients adjust to their situations, he would show them why life is worth living. They would become enlightened, rather than merely more ready to make their peace with common unhappiness, which was Freud’s more modest goal.

In The Doctor and the Soul, written soon after his release from the camps, Frankl argues that Freud was reductive and low-minded, a common charge among those who, like Frankl, call themselves existential humanists. They prefer to talk about the soaring human spirit, unlike Freud with his grubby interest in fetishes, perversions, and the like. But Freud is a permanent wisdom writer, who sways us with even his wrongheaded ideas. Freud can teach you something about almost any human subject: love, death, culture, war, religion, growing up. Whenever you reread him, you come away with a new insight.

Should life and death in a Nazi camp become the material for retail self-help manuals?

Frankl, by contrast, was a clichémonger, given to mouthing platitudes about true love, higher meaning, and the eternal soul. Faced with such starry-eyed idealism, Frankl’s reader suspects that he is merely trying to paper over the myriad possibilities for human disaster.

Man’s Search for Meaning bases its authority on Frankl’s concentration camp experience. Yet he misrepresented that experience in a strange way. Frankl spent only two or three days at Auschwitz before he was sent to Kaufering III, a subcamp of Dachau, where he had the wretched task of digging ditches and tunnels and laying railway lines. Near starvation, Frankl barely survived. Kaufering, where Frankl spent five months, and Theresienstadt, where he lived for two years, are never mentioned in Man’s Search for Meaning, while the name Auschwitz appears repeatedly.

Most readers of Man’s Search for Meaning assume that Frankl spent months at Auschwitz, not a few days. He writes that “the prisoner of Auschwitz, in the first phase of shock, did not fear death. Even the gas chambers lost their horror for him after a few days.” This seems doubtful, and in any case Frankl had no chance to test its truth.

There are other oddities in Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl never mentions that the vast majority of the prisoners in the death camps were Jewish. At the end of the book he writes, “Man is that being who has invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who has entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord’s Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips.” By citing the Christian prayer before the Jewish one, Frankl redefines the Holocaust as more than merely a Jewish catastrophe. Some of Frankl’s acolytes seem to share his wish to minimize signs of Jewishness. Daniel Goleman, in his introduction to Yes to Life, writes that Raoul Wallenberg issued “Swedish passports for thousands of desperate Hungarians.” They were desperate not because they were Hungarians, but because they were Jews.

Coming back to Vienna at the end of the war, Frankl reached a low point. When he heard the familiar phrases, “We did not know about it” and “We, too, have suffered,” Frankl “asked himself, have they really nothing better to say to me?” He added, in Man’s Search for Meaning, that his ex-neighbors’ “superficiality and lack of feeling was so disgusting that one finally felt like creeping into a hole and neither hearing nor seeing human beings any more.” Yet a mere two pages later Frankl recovers from his misanthropic bitterness and announces, “The crowning experience of all, for the homecoming man, is the wonderful feeling that, after all he has suffered, there is nothing he need fear any more—except his God.” Frankl wipes away his pessimism, bringing God onstage to make the survivor’s return into something “wonderful.”

Frankl downplayed the guilt of Austrian Nazis, even many decades after the war had ended. Stressing that there were good men among the SS, he absolved Austria of any responsibility for Nazi war crimes. In 1988 he accepted an award from Kurt Waldheim, who had been elected president of Austria in the face of a scandal: Waldheim had concealed his service in a Wehrmacht unit that massacred Serbian civilians. Along with Bruno Kreisky, Austria’s Jewish ex-chancellor, Frankl helped Waldheim rehabilitate his image. In the 1990s Frankl became close to Jörg Haider, the radical right-wing head of the FPÖ party, who liked to remind people that Hitler’s regime had done some good things, too.

Not all meanings are created equal. Patients recovering from a trauma may attach themselves to an authority figure, perhaps the leader of a radical right- or left-wing political movement. They might become conspiracy theorists, which is surely a way of filling life with significance. Frankl is uninterested in the transference that patients make to figures of authority, including the therapist. By contrast, Freud’s method is based on using transference and resistance, his two key terms.

Frankl peppered his writings with anecdotes showing how successful his logotherapy could be at helping people find meaning in their lives. But easy cases make bad law. Frankl never described how patients might show resistance to his techniques, and so we have no idea how he used their resistance. Instead, he implied that logotherapy is a magic cure-all.

Frankl’s work raises an enormous question: Should life and death in a Nazi camp become the material for retail self-help manuals? Frankl uses the Holocaust as an object lesson, showing how one can make meaning even in adversity. But he is also forced to admit that what prisoners went through in the camps was radically unlike what most people know.

“How we longed for proper human suffering at that time, real human problems, real human conflicts, instead of these degrading questions of eating or starving, freezing or sleeping, toiling or being beaten,” Frankl says in Yes to Life. “We thought back to the time when we still had our human sufferings, problems and conflicts and not the suffering and perils of an animal.” Yet later on in Yes to Life he remarks that there are “many cases” in which inmates “made inner progress, growing beyond themselves and achieving true human greatness, even in the concentration camp and precisely through their experience of the concentration camp.”

Here Frankl’s wishful thinking turns a devastating reality into a spiritual triumph. His need for such a victory is heartbreaking. It is also morally dubious, since the truly agonizing and destructive effects of the Shoah on its victims are whitewashed away.

Lawrence Langer comments that Frankl was “torn between how it really was and how, retrospectively, he would like it to have been.” A prisoner at one Nazi camp remembered that Frankl spent much time lamenting that he had turned down the chance to emigrate. Yet he depicts himself in Man’s Search for Meaning giving a heartening lecture to his fellow inmates in which he persuades them that “the hopelessness of our struggle did not detract from its dignity and its meaning.” They thank him with tears in their eyes.

The lecture probably did really take place. But Frankl’s memory is also clearly quite selective. For him, the moments of optimism are the real point of the camp experience. The prisoners’ despair, numbness, and degradation become mere background for his cathartic sense of moral uplift.

Frankl avoided the many painful cases of Holocaust survivors who were unable to reconcile themselves to their past torment. He focused only on those who achieved an optimistic, forward-looking life, people like himself, who could be inspirational examples for the rest of humanity. But Frankl’s “tragic optimism,” as he called it, turned away from the true pain of the Holocaust, which is the fact that it cannot be made into a source of moral inspiration. The horrors of the Shoah demand our attention, unsettling everything we thought we knew about human beings. Such a reality can never be a source of satisfying life lessons.

“If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering,” Frankl writes in Man’s Search for Meaning. “Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete.” Frankl sees the agonies we endure as what the Talmud calls yisurin shel ahava, the punishments of love, tests imposed by God to bring us closer to righteousness. And so the human being has what Frankl calls “the chance of achieving something through his own suffering.”

But even the Talmud has its doubts. Some torments are not edifying, and are not sent by God. As R. Yochanan interjects in Berakhot 5b, “Leprosy and [the death of one’s] children are not punishments of love.”

Viktor Frankl saw his own extreme suffering as a punishment of love, and in some ways he was a heroic example. But the Holocaust was not about heroism. Instead, the wicked swallowed the righteous, and evil prevailed over innocence. Not even a skilled therapist can heal such a wound.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.