The Jewish Auden

The poet’s philo-Semitism and visit to Jerusalem had a profound influence on him, and on Yehuda Amichai

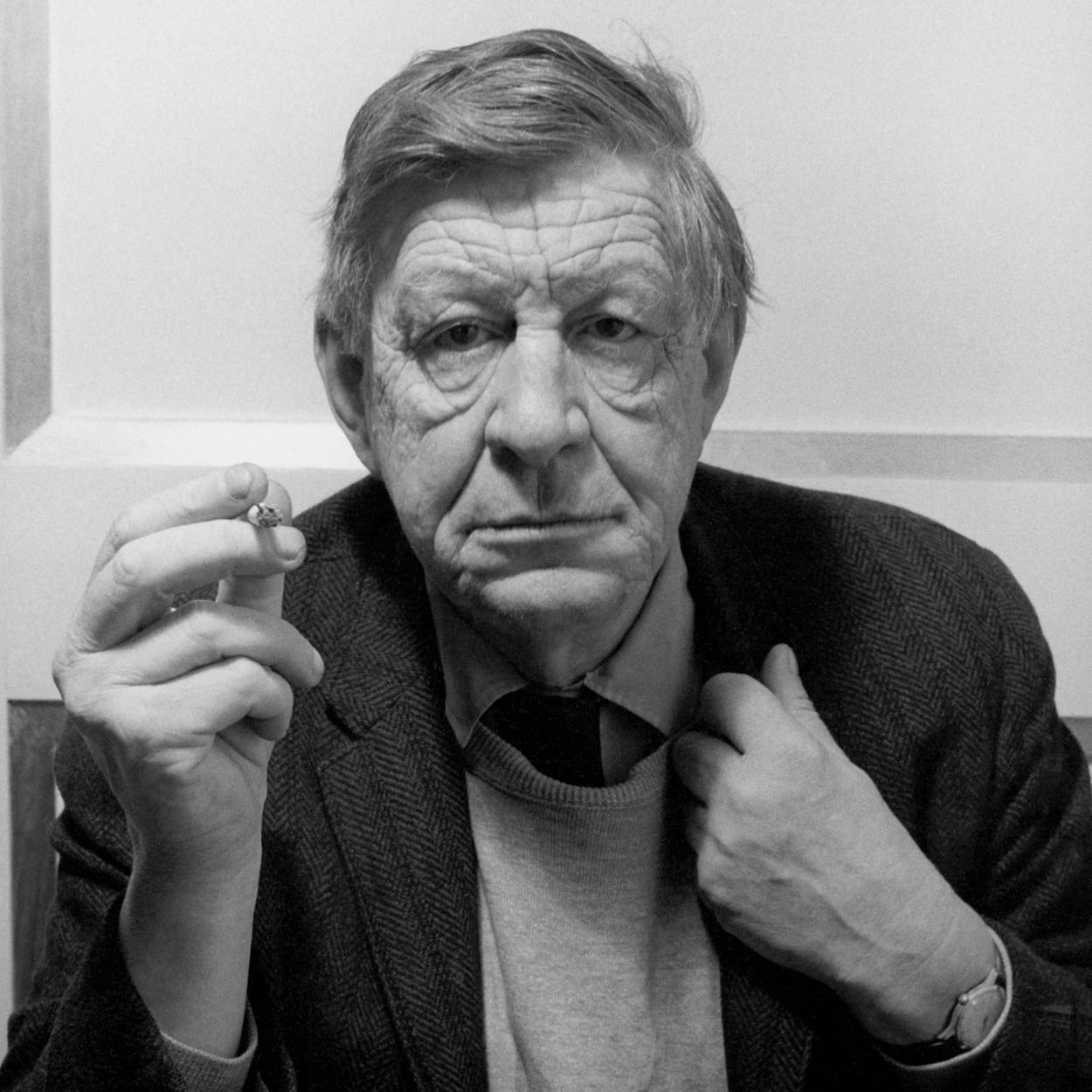

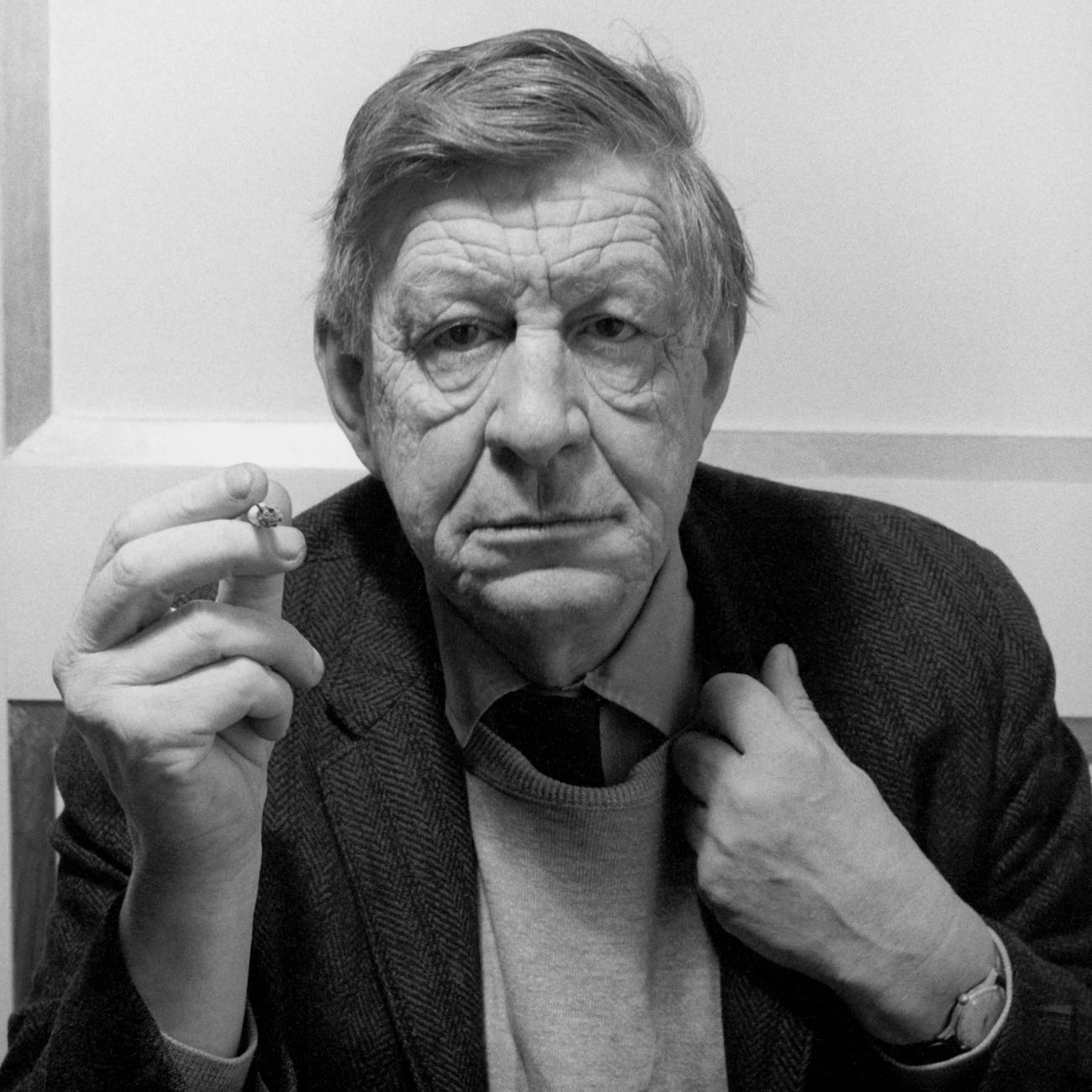

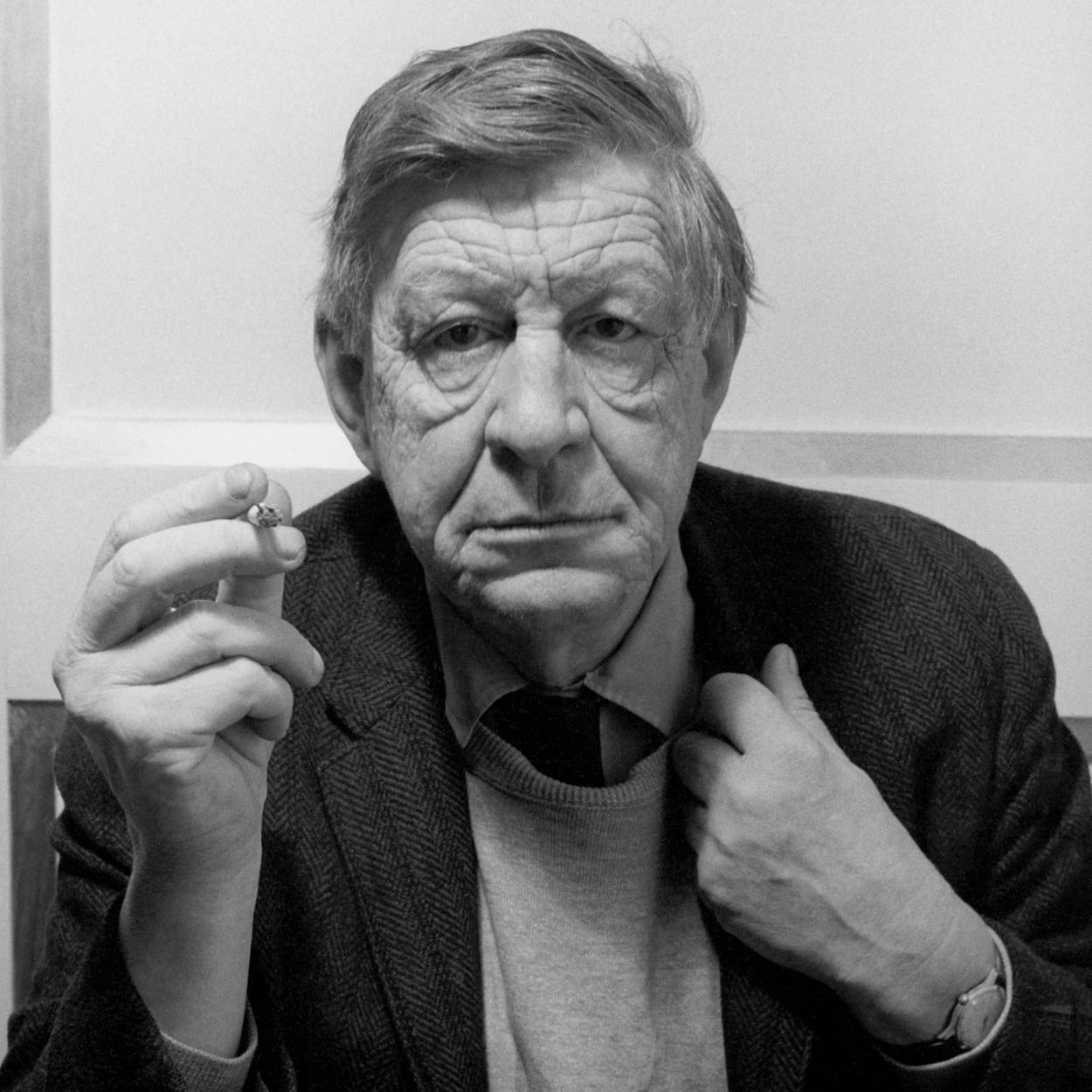

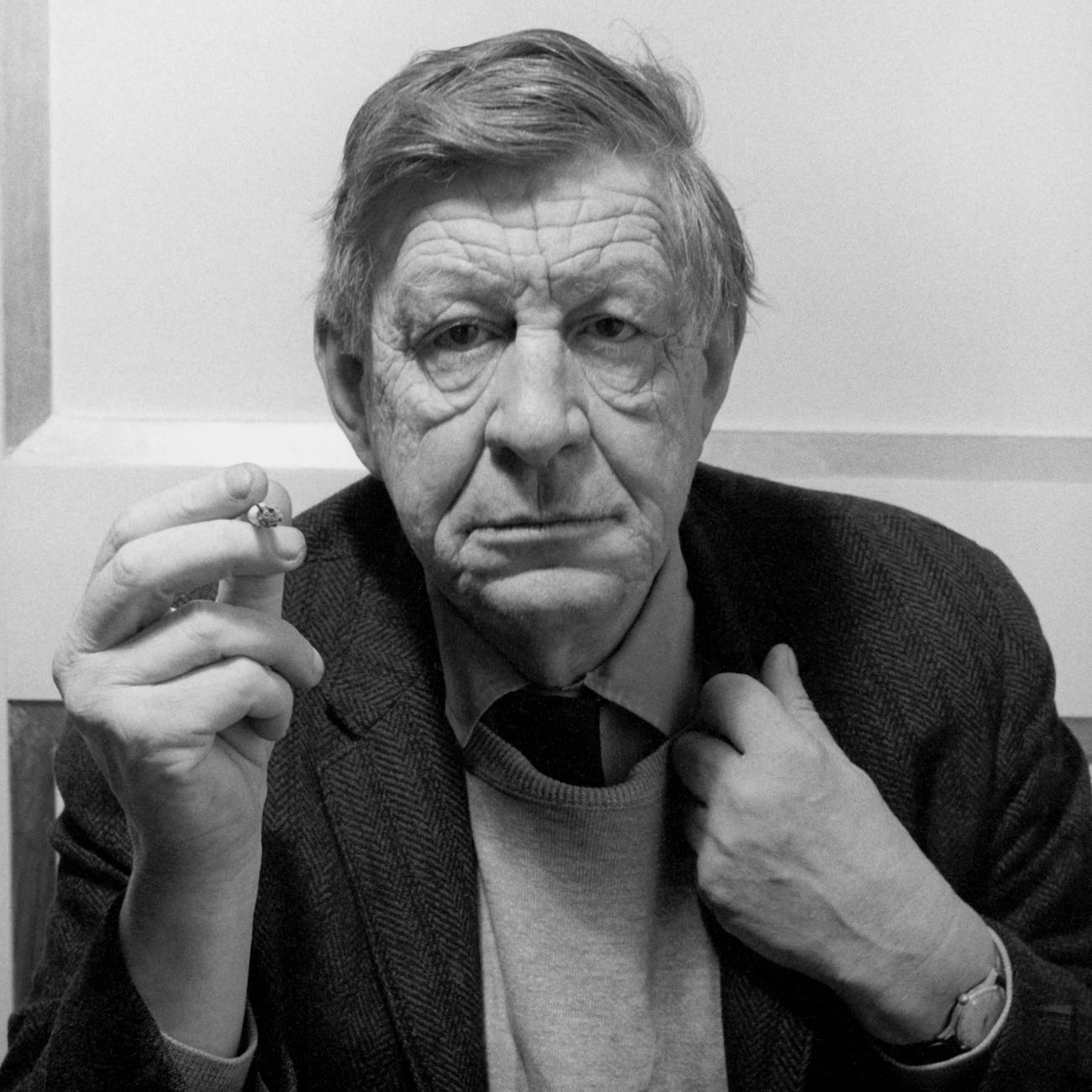

Among the many visitors who thronged to Jerusalem after the 1967 War was W.H. Auden, a poet with the status of an international celebrity. By the end of the 1960s Auden’s reputation as a serious yet accessible poet, a poet both British and American, was unparalleled in the English-speaking world. The American and European cultural upheavals of the late 1960s served only to solidify Auden’s reputation. Among intellectuals he had a wide range of admirers, one that encompassed academic literary scholars and Beat poets. Many readers admired the poetry and revered the poet. And among Auden’s readers were many who seldom read poetry. “Auden,” wrote critic Nicholas Jenkins in the TLS, “is a poet with ‘reach’—a figure of international stature within the realm of literature, but at the same time read by people who do not normally read much, or any, poetry.”

In 1970 W.H. Auden and his partner, Chester Kallman, visited Jerusalem. They were accompanied by their friend Alan Ansen, who had been a student of Auden’s since the 1940s. By the late 1960s Auden had yet to visit Jerusalem, though the Holy City had long been on the poet’s mind. As a Christian, he was aware of the city’s religious significance for the monotheisms. And as a thinker who called for a liberal Christian ecumenism, he thought of Jerusalem as a place where Christian unity might be strengthened, if not fully achieved. As early as in a 1947, in conversation with Alan Ansen, Auden speculated about the possibilities of the Christian churches achieving unity. “Yes” he said, “I have thought how the churches can be brought together. Where’s the only place to meet that would be satisfactory to all of them? Jerusalem, obviously. That’s a holy place for everybody.”

Auden had moved from England to the United States in 1939. On his arrival in New York City Auden, according to biographer Edward Mendelson, immersed himself in the intense, argumentative life of Jewish exile intellectuals. But it was not only the exiles from Hitler’s Germany that Auden sought out. Native New Yorkers and the artists and poets who flocked to the city from all over the United States also fascinated Auden. The argumentative style of New Yorkers, Jewish and non-Jewish, drew him in. Auden was often heard to say that the only people he enjoyed talking to in New York were Jews. Before arriving in New York Auden had few Jewish friends; and he claimed that before he attended Oxford University, he had never met a Jew. In New York he found himself in political and literary circles in which Jews were very active. The demographic reality should not be overlooked here: In 1939, some 25% of New Yorkers were Jews. As Edward Mendelson noted, “Auden left England with the half-formed resolution that he would begin his career anew in a new country.” Auden often described himself as “not an American, but a New Yorker.”

Within a year of moving to New York, Auden also experienced a religious conversion, a renewed commitment to Christian doctrine and practice. His religious awakening was linked to his disillusionment with the politics of the international left, which he had long championed. When he went to Spain in 1936 to volunteer as an ambulance driver for the Republican forces “he was scorned and ignored because he didn’t happen to be a member of the Communist Party. In Spain he first experienced the totalitarianism of the Left, and the first stirrings of his return to religion can be traced to his unexpected distress at finding the churches in Barcelona vandalized or blown up and the clergy systematically mistreated.”

In 1940 Auden began to attend church in Brooklyn Heights, where he was then living, and within a few months he was taking Communion regularly. Auden’s description was that he was a “would-be Christian.” “Christianity,” Auden said, “is a way, not a state, and a Christian is never something one is, only something one can pray to become.” Despite this stated aversion to a Christian label, Auden formally converted to Anglicanism in 1941.

The poems of Auden’s first decade in New York are poems of exile and poems of love inspired by his relationship with Chester Kallman. Critic Nicholas Jenkins wrote, “After falling in love with Chester Kallman, whose Jewishness offered Auden access to a world entirely different from his own, Auden almost immediately wrote a number of serenely happy love poems.”

Though he affirmed his commitment to Christian belief and practice, Auden flirted briefly with the possibility of conversion to Judaism. In the mid 1940s Auden told his New School student Alan Ansen, “I’ve been increasingly interested in the Jews. … I wonder what might happen if I converted to Judaism.”

W.H. Auden was often heard to say that the only people he enjoyed talking to in New York were Jews.

Was Auden joking here? Hadn’t he become a serious Christian only a few years earlier? I would venture that this was one of the poet’s more serious jokes. John Fuller has noted that, “Auden’s Christian jokes about Jews are always deeply serious. See, for example, his dislike of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, which he felt embodied a ‘not very savory wish to make the Mother of God an Honorary Gentile.’”

Long before Auden moved to New York City and fell in love with Chester Kallman—and through him with the polyglot, multi-ethnic life of New York City—he had expressed sympathy for the persecuted Jews of Germany and distaste for the anti-Semitism in the work of T.S. Eliot and other poets. In his 1939 poem “Refugee Blues,” Auden expressed deep sympathy for Europe’s Jewish refugees and deep anger that these refugees found no home in the West.

Thought I heard the thunder rumbling in the sky;

It was Hitler over Europe, saying, ‘They must die’:

O we were in his mind, my dear, O we were in his mind.

Saw a poodle in a jacket fastened with a pin,

Saw a door opened and a cat let in:

But they weren’t German Jews, my dear, but they weren’t German Jews.

While over the decades Auden referred to Kallman’s Jewish roots both in his own poetry and in his prose, Kallman himself avoided the subject of Jewishness assiduously. It would be close to 30 years after Auden moved to New York that Kallman would make any literary gesture toward his own Jewish identity, and that gesture was tied to Israel.

In an article in The Nation from September 1944, Auden used his review of Waldo Franks’ book, The Jew in Our Day, to speculate about the psychological-emotional forces that generated anti-Semitism. Frank’s book has an introduction by Reinhold Niebuhr, in which the prominent Protestant theologian made the case for Zionism. In his review Auden offers his thoughts on that political movement. In general, Auden states, he rejects all forms of national statehood as “nothing more than a technical convenience.” But in the Jewish case he agreed with Niebuhr that “as long as there are nation states in which Jews are, overtly murdered en masse, the demand for a Jewish homeland is politically justified … but so long as no one enjoys the full advantages of statehood one cannot congratulate those who do not on being spared its temptations.”

In the same period in which Auden repeatedly expressed his sympathy for Europe’s Jews and his support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, poets and writers in British mandate Palestine were writing a new Hebrew poetry influenced by Auden. Foremost among these young writers was Yehuda Amichai, who had served as a soldier in the Jewish Brigade of the British army in World War II.

In many interviews and conversations, Amichai told of his discovery of a copy of The Faber Book of Modern Verse, while serving in the Egyptian desert. He was 18 years old. A British army library van was stuck in the desert and Amichai and his fellow soldiers, hungry for reading material, ‘liberated’ a few volumes. As Amichai told a Paris Review interviewer in 1992:

One event in Egypt had an extremely important impact on my life. It was in 1944, I think, we were somewhere out in the Egyptian desert. The British had these mobile libraries for their soldiers, but of course most of the British soldiers, being from the lower classes and pretty much uneducated, didn’t make much use of the libraries. It was mostly us Palestinians who used them—there we were, Jews reading English books while the English didn’t. There had been some kind of storm and one of the mobile libraries had overturned into the sand, ruining or half-ruining most of the books. We came upon it and I started digging through the books and came upon a book, a Faber anthology of modern British poetry, which I think came out in the late thirties. Hopkins was the first poet, Dylan Thomas the last. It was my first encounter with modern British poetry—the first time I read Eliot and Auden, for example, who became very important to me. I discovered them in the Egyptian desert in a half-ruined book. This book had an enormous impact on me—I think that was when I began to think seriously about writing poetry.

Amichai immersed himself in the work of British and American poets, and to some extent sought to emulate their work, especially that of Auden’s. A decade after the war ended, in 1955 Amichai, by then an emerging literary figure on the Israeli cultural landscape, visited the U.S. In New York City he availed himself of the opportunity to hear Auden give a reading at the 92nd Street YMHA. The experience of seeing and hearing his favorite English-American poet “read” in public was for Amichai a mixed experience, one that shifted his perception of a poet’s role.

Auden’s use of the English and American vernaculars influenced Amichai’s poetic language. But what Amichai saw of Auden’s public persona disturbed him. He decided then that he would not be that type of “performer” that he thought Auden had become; he would not pander to popular taste.

The effect that hearing Auden read had on me was to blend the different strata of my life … It was like a drill that penetrates different strata of earth, oil, and water and mixes them together. Perhaps that is one of the true aims of poetry: to open, drill, mix, and to then close, organize, and calm.

The poems Auden chose to read, Amichai suggests, were not his greatest. They were somewhat cruel and snarky, and Auden’s delivery often more so.

Auden spoke quickly and quietly and did not look at the audience while he read. He read as if forced to; not as if he wanted to. Listening to his poems made me sad. The lines in them were beautiful, and the ideas original. But I began to ask myself, what had Auden done to himself, made himself? For these reasons I didn’t join the audience’s frequent outbursts of nervous laughter. Yes— many of the words and ideas were funny … but I didn’t laugh.

Auden, in Amichai’s view, was posturing for the “bored intellectuals” in the 92nd Street Y audience. For Amichai, the reading was something of a ghoulish experience. Auden, he wrote, “continued reading his poems as if he was reading them from the grave, after his death.”

After the reading, Amichai, in a conversation with an American friend, said, “So this is what Auden has become!” To which his friend replied, “look, we too will be like that someday.” But, despite the bad feeling he and his companion had about the reading, Amichai was forced to admit that, “Despite that, Auden’s poems, with their sadness lurking behind the mockery, are wonderful.” In 1966, more than a decade after that New York City reading, Amichai was invited to read at the Spoleto International Arts Festival. There he met Auden, Ezra Pound, and other influential poets and read from the podium with them.

By the mid 1960s it was clear to careful readers of Israeli poetry that of the poets in that Faber anthology, it was Auden who had influenced Amichai the most deeply. It was Auden’s ability to use the contemporary English vernacular in his verse that influenced Amichai to incorporate the Hebrew vernacular into his own poetic forms. Speaking of Amichai and other Israeli poets of his generation, poet and critic Dennis Silk noted that, “The major influences from abroad have so far been in the direction of a colloquial language, closing the once huge gap that existed between the direction of the poem and what gradually emerged as the true spoken language. Flatness, the prosaic perspective of the streets, came to the younger poets mainly via Auden.”

Throughout the 1960s Auden and Amichai were often in contact, most often at poetry festivals on the international circuit. By that time Yehuda Amichai had become “Israel’s Auden.” His poems about love, war, and loss were read at weddings and military funerals. Soldiers off to military service often had a copy of Amichai’s poems in their kitbags. Lovers exchanged copies of Amichai volumes. And in his now more frequent public readings in Israel and elsewhere Amichai was charming, friendly, and affirming: The negative lessons learned from observing Auden’s 1955 reading at the 92nd Street Y stayed with him.

In 1970 Auden, Kallman, and Alan Ansen flew to Tel Aviv from Athens, where Chester Kallman kept an apartment. In Jerusalem the three literary pilgrims stayed at the Intercontinental Hotel. Only later did Ansen realize that though he had requested that their European travel agent book them into Jerusalem’s American Colony Hotel, they were booked into the Intercontinental in error. This was an unfortunate choice, as the hotel, perched atop the Mount of Olives, was not within walking distance of the streets of the Old City.

Reinhold Niebuhr’s widow, Ursula, introduced Auden to Jerusalem’s charismatic mayor, Teddy Kollek. Renowned for feting international celebrities, Kollek arranged a reception for Auden and took the poet and his companions on a nighttime tour of the “united city.” Auden, however, found Israel’s political and military control of the Arab parts of the city disconcerting; though he refrained from saying as much to Kollek and his other Israeli hosts, he demonstrated no such restraint with his traveling partners. As Ansen recalled, “Auden didn’t believe Jerusalem should only belong to Israel, and expressed this opinion privately to me.”

From Jerusalem, Auden, Kallman, and Ansen traveled to Masada. They also visited the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot. These secular shrines to Israeli nationalism impressed Auden less than Israel’s sacred places, though he was no doubt aware of the dubious historicity of the holy sites. Visiting Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity, Auden turned to Kallman and Ansen and said, “This is the one place where one feels He might really have been present.”

In his poem “The Dome of the Rock: Jerusalem” (1970), Chester Kallman evoked a day of the group’s activities in Jerusalem. After a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Auden, Ansen, and Kallman walked to the Western Wall plaza and then ascended to the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif. Kallman, invoking the spirit of Auden, in whose memory the poem was written, describes their pilgrimage as one made by “two Jews by birth, one practicing Anglican.” But despite their intense day of exposure to the holy places of the three monotheistic traditions, the three visitors were not transformed by the experience; they remained in Kallman’s words, “eternal tourists, never quite at home.”

Shalom Goldman is Professor of Religion at Middlebury College. His most recent book is Starstruck in the Promised Land: How the Arts Shaped American Passions about Israel.