Wall of Crazy

Phil Spector and Leonard Cohen’s incredible album, released 35 years ago, is a time capsule of American pop music

This month marks the 35th anniversary of the most famous album you’ve probably never heard. Its creators, Leonard Cohen and Phil Spector, couldn’t have been more poorly matched: one, the audacious composer of teenage pop symphonies who had by most accounts gone entirely crazy, the other the singer of small and sad songs accompanied by grim guitars. What they created, after many nights of writing in Spector’s Los Angeles mansion and many days of recording in a studio dense with musicians, guns, and backup singers like Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg, was grotesque but also supremely interesting. All there is to know about the history of American pop music, about the place of Jews in American culture, about Cohen, about Spector, is there in Death of a Ladies’ Man. And it all boils down to one moment: One night, at around 4 in the morning, as another recording session cascaded to an end, Spector stumbled out of his booth and into the studio. In one hand, he held a .45 revolver; in the other, a half-empty bottle of Manischewitz sweet kosher wine. He put his arm around Cohen’s shoulder and shoved the revolver into the singer’s neck. “Leonard,” he said, “I love you.” Not missing a beat, Cohen replied, “I hope you do, Phil.” The rest is commentary.

***

The impact of the 1974 crash was so strong that years later Phil Spector was still picking out shards of glass from his face. Nearly 700 stitches were required to patch him back together—300 to his face and 400 to the back of his head. The first responders to arrive on the scene of the accident, on Melrose Avenue, took a look at Spector’s totaled Rolls Royce, and then at his small body, which had flown out of the car’s window and lay in a bloody knot a few feet away. They assumed he was dead; it took a careful police officer a few seconds to make out a faint heartbeat and rush Spector to a hospital.

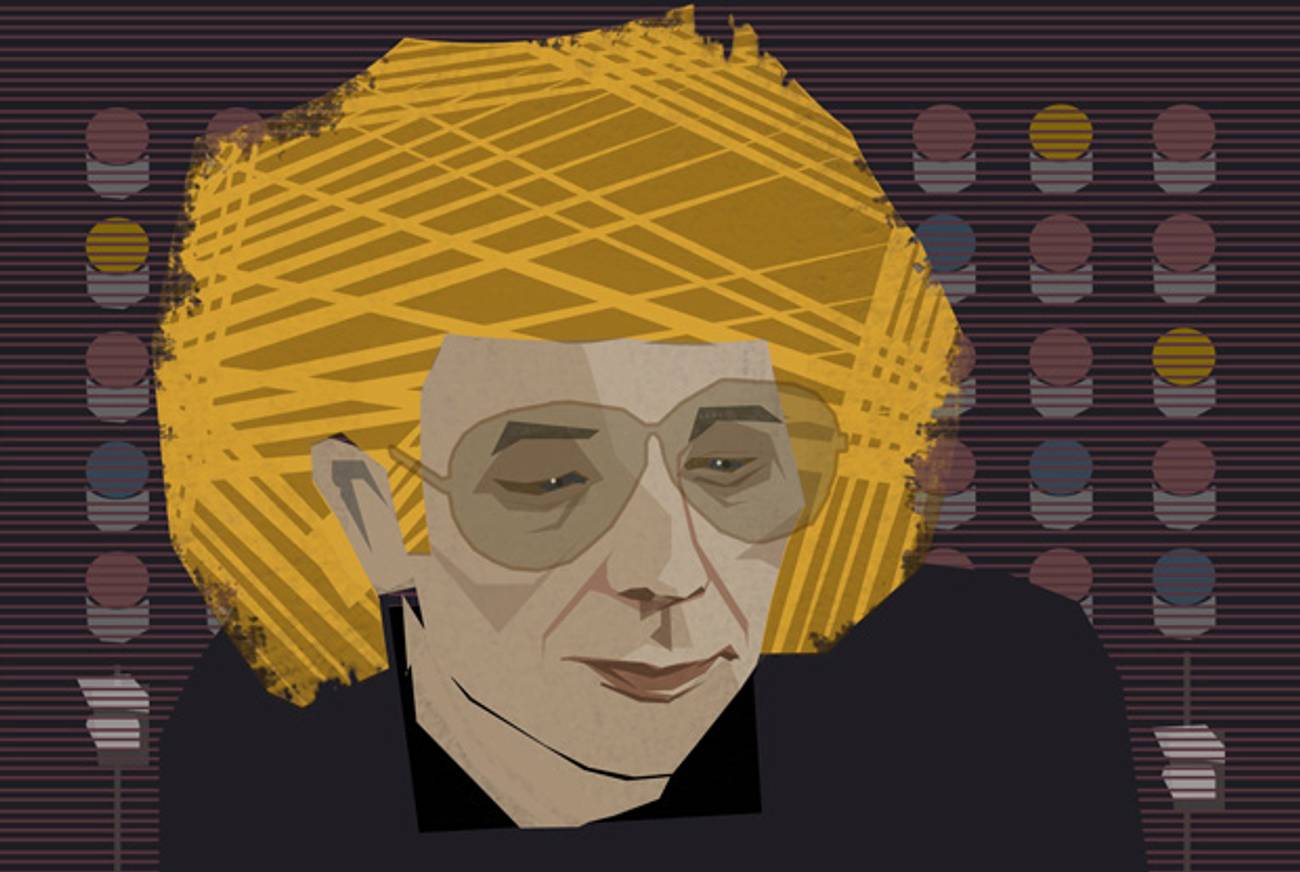

The man who emerged, weeks later, wasn’t the same. There were the externalities: His hair having been burnt to a crisp, he comforted himself with a series of wigs that grew more audacious the darker his mood got, from a standard brown mop-top to a mess of golden tresses à la Bo Peep. The deeper wounds, however, needed more radical balms: Spector’s love of guns grew morbid, and his bodyguards, previously nothing more than a fashion statement, now swarmed around him wherever he went, weapons bulging beneath cheap jackets.

Spector’s morbidity couldn’t have come at a worse moment for a man who in the spring of 1974, just before his accident, was busy being reborn. Having initially set off to train as a court reporter, Spector became a musician instead, had a No. 1 hit with “To Know Him Is To Love Him”—the song’s title was taken from his own father’s tombstone—and then quit his band and became a music producer. Between 1961 and 1965, he put out more chart toppers than anyone else—“He’s a Rebel,” “Be My Baby,” “Walking in the Rain,” “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” “Unchained Melody”—and elevated pop into an art form worthy of the most serious consideration. Then, with much of American popular music hemmed in by his famous Wall of Sound, he disappeared into a reclusive life with his new wife. When he appeared in public, it was often to take on a host of strange film and television cameos, including playing a drug dealer in Easy Rider and himself on I Dream of Jeannie. Whatever friends he had left heard him speak incessantly about the music business being unsalvageable, a depressing racket, a bad marriage between untalented hacks and their stupid and doting audiences. There was no one out there he wanted to work with, he said, no one big enough or good enough.

Except, maybe, for the Beatles. When the Fab Four, on the cusp of collapse as a band, wanted to turn a few forgotten sessions into one last studio album, they invited Spector to take a stab. The tapes he received were in keeping with the band’s original idea of an intimate, stripped-down recording with many live takes. One of the songs, for example, was a pretty piano ballad called “The Long and Winding Road,” which Spector thought was much too spare. To McCartney’s plaintive voice he added 18 violins, four violas, four cellos, three trumpets, three trombones, two guitars, and a choir of 14 women. McCartney cared deeply for the song and told an interviewer he had written it instead of having to go see a shrink; Spector’s version robbed it of all of its intimacy, turning it from a small and personal tune to a symphony of existential pain. Nine days after hearing Spector’s mix, McCartney, enraged, announced that the Beatles were no more.

Spector didn’t particularly care. His Let It Be became a major hit and, released as a film, won an Academy Award. He produced George Harrison’s masterpiece, All Things Must Pass, oversaw the momentous charity concert for Bangladesh and gave John Lennon some of the best recordings of his solo career. He was still erratic and was popping pills at an alarming rate, but he had regained his appetite for production, teaming up to create a new label in partnership with Warner Bros. and looking out for new artists. And then came the car crash.

Recovering slowly, Spector took a few more turns at the console, producing singles for Cher and a beautiful album for Dion, but as the 1970s drew to a close he seemed, personally and professionally, beyond redemption. The man who had once known better than most what the public wanted had fallen out of tune with America. The music that played in Phil Spector’s head was not written by the Ronettes or the Crystals or even the Beatles; it was written by history. The son of a failed father who had killed himself when Spector was 9, a scrawny and small Jew from the Bronx transplanted to California where the weather and the people made him sick, Spector needed all that heavy instrumentation to hide the thudding beats of anxiety. America concurred: Experiencing an economic boom and a cold war simultaneously, it needed a soundtrack that masked all its insecurities and violence and rifts with sweet ooh-las and da-doo-ron-rons.

America, then, sounded very much like Phil Spector, until it didn’t, until war and social tensions broke loose and psychedelics changed everything and big money changed everything again. In the new America, nobody cared very much for the Wall of Sound, or for its psychic engineer.

The same psycho-cultural predicament had, for different reasons, captured Leonard Cohen. By 1977, Cohen was 43; having started out as a poet and a novelist, he came to music late in life and was a decade or so older than most of his peers on the scene. He had released four albums since his debut a decade prior; none were very well received, at least not in the United States.

The problem was not in his songs but in his self. Sung by others, most notably Judy Collins, Cohen compositions such as “Suzanne” and “Sisters of Mercy” became smash hits, but his own versions were too spare and, most agreed, too depressing. And he seemed to be getting worse: Whereas his first two albums were merely melancholic, the third, 1971’s Songs of Love and Hate, was downright grim. By the time the fourth rolled in, in 1974, Cohen could refer to himself in song as the “grocer of despair,” knowing well that despair wasn’t something that Americans, perpetually cheery, were eager to buy.

And yet despair, of a particularly maudlin variety, was what most listeners believed that Cohen was selling. His humor, his depth, and his subtlety were lost on the majority of his audience. His songs were deeply intimate—he had frequently referred to them as diary entries set to guitar music—and rich with allusions that far transcended the simple and stentorian vocabulary popularized by Spector and the other captains of the music industry. As one critic remarked, after visiting Cohen’s room at the Chelsea Hotel, “the drapes are as florid as his verse.”

Simply put, while Spector was a priest, cultivating the rituals of a new religion he had helped to create, a religion of rock ’n’ roll, Cohen was a prophet, an artist who sought new ways to speak ancient truths. On his fourth album, for example, he reworked the Unetaneh Tokef, a Jewish liturgical poem that is recited on Yom Kippur, into “Who by Fire,” paraphrasing the prayer’s list of the various ways in which those who have displeased the Lord might find their end—avalanche, barbiturate, hunger—and then adding the line “And who shall I say is calling?” The prayer concludes differently: After counting the ways in which the Almighty may smite his subjects, it comforts by reminding us mortals that “repentance, prayer, and charity avert the severe decree.” Cohen, however, remained defiant. Rather than prostrate himself before the Lord, Cohen coolly reacted to the divine decrees as if they were nothing more than a phone call from a stranger, meriting distance and a hint of suspicion. Before he succumbed to any grim fate, the singer wanted to know just who was doing the judging.

It was a much more radical approach, not only to art but also to Judaism, and it frequently incurred the wrath of Cohen’s family and friends. Early on in his career, while still only a young Canadian poet, he spoke at a Montreal Jewish event and chided the community—his own—as having lost sight of the religion’s true meaning and instead becoming obsessed with building institutions, endowing buildings, and other markers of worldly power and wealth.

Leonard Cohen didn’t know Phil Spector when he gave his Montreal talk, but he may as well have been talking about him when he chided his fellow Jews for becoming obsessed with wealth and power. Wealth and power were what Spector was about: not strictly for their own sake—that would be crass—but as means to enacting a highly personal power-tripping aesthetic vision that could turn an asthmatic, diabetic, scrawny kid into the center of the coolest scene in the world. Cohen, on the other hand, was the anti-Spector, the teenager who was always well-liked yet never felt quite at home, the scion of the prominent Jewish family who nonetheless felt the whole community was built on a sham. Instead of trying to take over the world, he struggled to make sense of it, to see it in all its splendid and tragic nuance—an effort that placed him perennially on the outside of whatever inside there was.

And yet, when Cohen’s manager suggested cutting an album with Spector, the singer was intrigued. On the surface, the idea sounded like a disaster: Cohen had so reviled previous producers’ attempts to enrich his monastic sound that he took over the tapes and finished the mix himself, condemning all previous instrumentations to the background and refusing even rock staples such as drums. But other factors triumphed. There were obvious biographical similarities: Both men were born to upper-middle-class Jewish families; at age 9 both had lost their fathers (Cohen’s died of an illness); and both were fond of their immigrant grandfathers, with their strange accents and old-world religion. Both found solace in music, communicating better in song than they did in any other way, and both approached their craft in an intensely personal way, channeling all their hurt and hope and lust into chord changes and refrains. Cohen was stronger with the lyrics, Spector with the tunes; the manager they shared, Martin Machat, suggested that they get together and see if they could collaborate on an album. Both clients, Machat realized, badly needed a hit.

The collaboration got off to a rocky start. When Spector first invited Cohen and his wife for dinner at his house, he flew into a rage when the couple, tired after a long meal, got up to leave, and ordered his servants to lock them inside. The Cohens remained seated, surrounded by Spector’s armed guards. They were freed only in the morning, but Cohen was unfazed. Spector was a lunatic, Cohen seemed to understand, but he was the right kind of lunatic. Unlike Bob Dylan, he didn’t dismiss songs as commodities, not too different from brooms or brushes, objects to be repackaged and resold. Songs, to Spector, were sacramental, and they were that for Cohen as well, which is why the singer found himself, a few days after that first disastrous dinner, once again knocking on Spector’s door. This time around, the two clicked, spending the entire night talking about the songs they’d heard on the radio as children.

“He really is a magnificent eccentric,” Cohen said of his collaborator in an interview, years later. “And to work with him just by himself is a real delight. We wrote some songs for an album over a space of a few months. When I visited him we’d have really good times and work till late in the morning. But when he got into the studio he moved into a different gear, he became very exhibitionist and very mad.”

His madness was evident at first sight. As Cohen entered the studio in January of 1977 to begin recording the new album, he saw, in his biographer’s words, “a room crammed with people, instruments and microphone stands. There was barely space to move. He counted forty musicians, including two drummers, assorted percussionists, half a dozen guitarists, a horn section, a handful of female backing singers, and a flock of keyboard players.”

Orchestrating this cacophony was Spector, standing behind his console, screaming, ordering people to do exactly as he said. Dylan and Allen Ginsberg, who were brought in to sing background vocals on a song called “Don’t Go Home With Your Hard On,” weren’t spared. Listening to his playback, Spector played the music so loud that he caused the speakers to explode at some point and had to relocate the entire session to another studio. He was perpetually drunk and never unarmed; others in the studio, including Spector’s bodyguards, were similarly liberal about mixing drugs and weaponry. “With Phil,” Cohen recalled years later, “especially in the state that he found himself, which was post-Wagnerian, I would say Hitlerian, the atmosphere was one of guns, I mean that’s really what was going on, was guns. The music was subsidiary, an enterprise, you know people were armed to the teeth, all his friends, his bodyguards, and everybody was drunk, or intoxicated on other items. … I remember the violin player in the song ‘Fingerprints,’ Phil didn’t like the way he was playing, walked out into the studio, and pulled a gun on the guy. Now this was, he was a country boy, and he knew a lot about guns. He just put his fiddle in his case and walked out.”

But Spector’s eccentricity in the studio wasn’t the real problem; each day, accompanied by his goons, he would take the master tapes to his car and whisk them away to his house. He had done the same thing with Let It Be. He would mix the album as he saw fit and present it to Cohen as a fait accompli. It was not an arrangement any artist would gladly accept, especially when there were signs suggesting that somewhere amidst the fog of booze and bullets, Spector had lost track of any vision he might have had for the album. “I’ll tell you something, Larry,” he wrote in a note he scribbled on the master tapes to his long-time engineer, Larry Levine, “we’ve done worse with better, and better with worse!”

When the album, Death of a Ladies’ Man, was finally released, in November of 1977, most critics and nearly all of Cohen’s fans saw it as a farce. Here, they argued, was Cohen’s delicate poetry drowned by sound, his voice barely audible on some of the tracks given Spector’s cacophony. The critics were right, but for all the wrong reasons. Musically, the album is a marvel, the kind of rare work that manages both to entertain and to provide a clever disquisition on its own genre.

Take the album’s best-known track, “Memories”: It’s a grand doo-wop anthem, and it ends with a snippet from The Shields’ 1958 hit “You Cheated, You Lied,” which it closely resembles. Hearing the newer song melt into the older one delivers a brutal jolt of emotion. Here is doo-wop, two decades later, its promises all soured. It is sung now not by the sweet-voiced youths that Spector was so good at finding and cultivating (and sometimes destroying) but by a raspy-sounding middle-aged man. The Shields’ song conveyed the genteel sadness of broken-hearted teenagers who grieved for an affair gone bad but who sensed, however unconsciously, that they had their entire lives ahead of them to fall in love all over again. Working with more or less the same tune, Cohen sounded desperate as he sang about walking up to the tallest and the blondest girl and asking to see her naked body. He cast himself as the same doo-wop crooner, 20 years older, realizing that heartbreak wasn’t a sweet and passing sorrow but a permanent state of being, now seeking not romance but meaningless sex. The melody is louder and more frayed, almost hysterical.

The real problem with Death of a Ladies’ Man was not the weird marriage of musical styles but its spiritual message. Spector hadn’t just made Cohen sound different; he made him sound crass. Cohen himself admitted as much: Playing “Memories” a few years later in Tel Aviv, he introduced the song with an apology. “Unfortunately,” he said, “for my last song, I must offend your deepest sensibilities with an entirely irrelevant and vulgar ditty that I wrote some time ago with another Jew in Hollywood, where there are many. This is a song in which I have placed my most irrelevant and banal adolescent recollections. I humbly ask you for your indulgence, as I look back to the red acne of my adolescence, to the unmanageable desire of my early teens, to that time when every woman shone like the eternal light above the altar place and I myself was always on my knees before some altar, unimaginably more quiescent, potent, powerful, and relevant than anything I could ever command.”

In all of his other explorations of the flesh in song—and it’s hard to think of a contemporary artist who wrote about copulation more frequently or more eloquently than Cohen—the singer realized that the body is only worthy of art’s attentions if it exists in search of a soul. It’s a duality Cohen captured best, perhaps, in his most famous song: “And remember when I moved in you,” he stated, “The holy dove was moving too/ And every breath we drew was Hallelujah.” But Spector forced Cohen to abandon the spirit and record instead an album thick with profanities in which the singer’s main yearning is not to be saved but to get laid.

For that reason alone, the album deserves our ire. But it also deserves our respect: 35 years after its release, Death of a Ladies’ Man remains one of the most audacious attempts to look at that sobering mixture of longing and regret that makes up so much of life, not bitterly (as Lou Reed, for example, had done in several of his albums) or nostalgically (like too many aging rockers to count) but candidly and, sometimes, humorously. To achieve that, you needed a Cohen and a Spector, a Yin and a Yang, the one translating his darkness into precious and overwhelming pop symphonies and the other expressing his essential faith in mankind in spare verses and with a grim guitar. The album, then, offers its listeners a strange existential litmus test of sorts: Whether you look upward to heaven or down at your crotch says everything about how you choose to approach adulthood. The clash is not only artistic; it is theological. And it makes for an album that is frequently terrible, deeply relevant, and not for one moment boring.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.