War Papers

A trove of medieval scrolls, smuggled out of Afghanistan into the hands of London art dealers, could shed new light on a once-vibrant Jewish heritage

Afghanistan for many people is synonymous with the War on Terror, radical Islamic movements such as the Taliban and al-Qaida, and a state of almost perpetual instability. However, recent reports of the discovery of some 150 medieval Judaeo-Persian manuscripts purporting to be from Afghanistan, possibly worth several million dollars on the open market, open a window to a very different place. At the same time, they offer scholars a chance to learn more about a little-known Jewish heritage. Though they cannot compare to the thousands of works of the Cairo Geniza or the Dead Sea Scrolls, these manuscripts are the most important cache of Jewish documents ever to have been found in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan, despite having passed in 2004 draconian laws against the trade, removal, or excavation of heritage sites, has been a free-for-all for looters and pillagers for more than 30 years. Today the preservation of the country’s rich heritage, both Islamic and pre-Islamic, remains very low on the priority list of the Karzai government, which commits only a token sum of its annual budget to protection measures. It is left to UNESCO, a few dedicated, underpaid officials, and a handful of foreign archaeologists to battle against what is a well-connected and highly organized trade in illegal antiquities, in which government officials have sometimes been implicated.

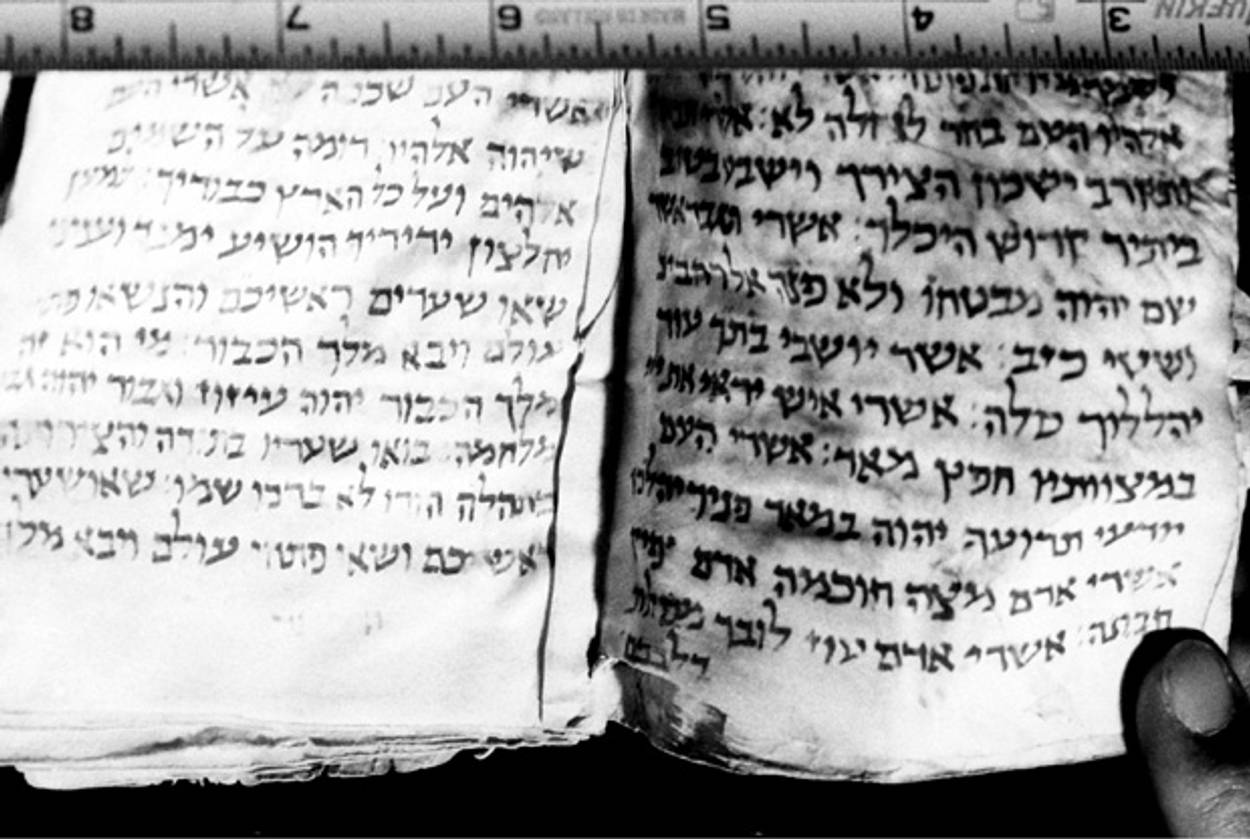

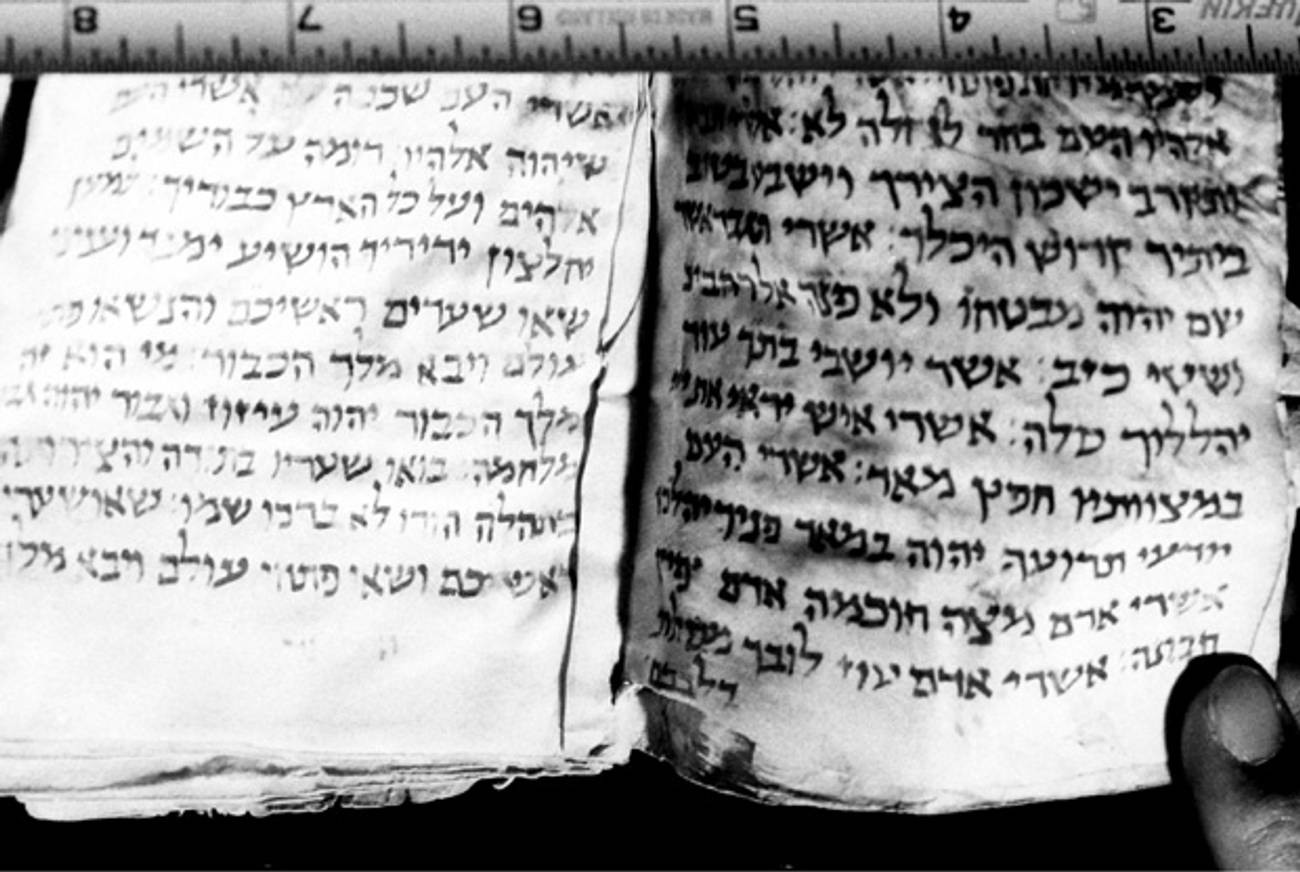

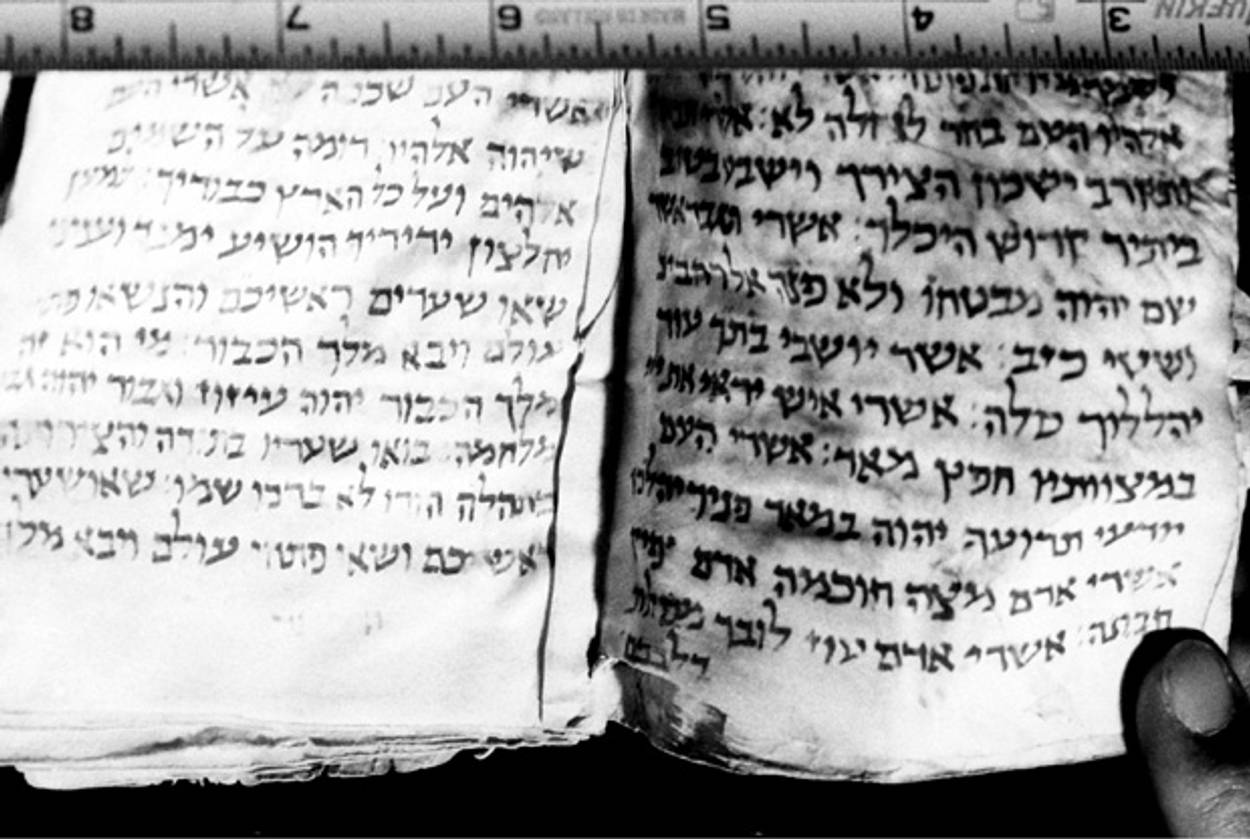

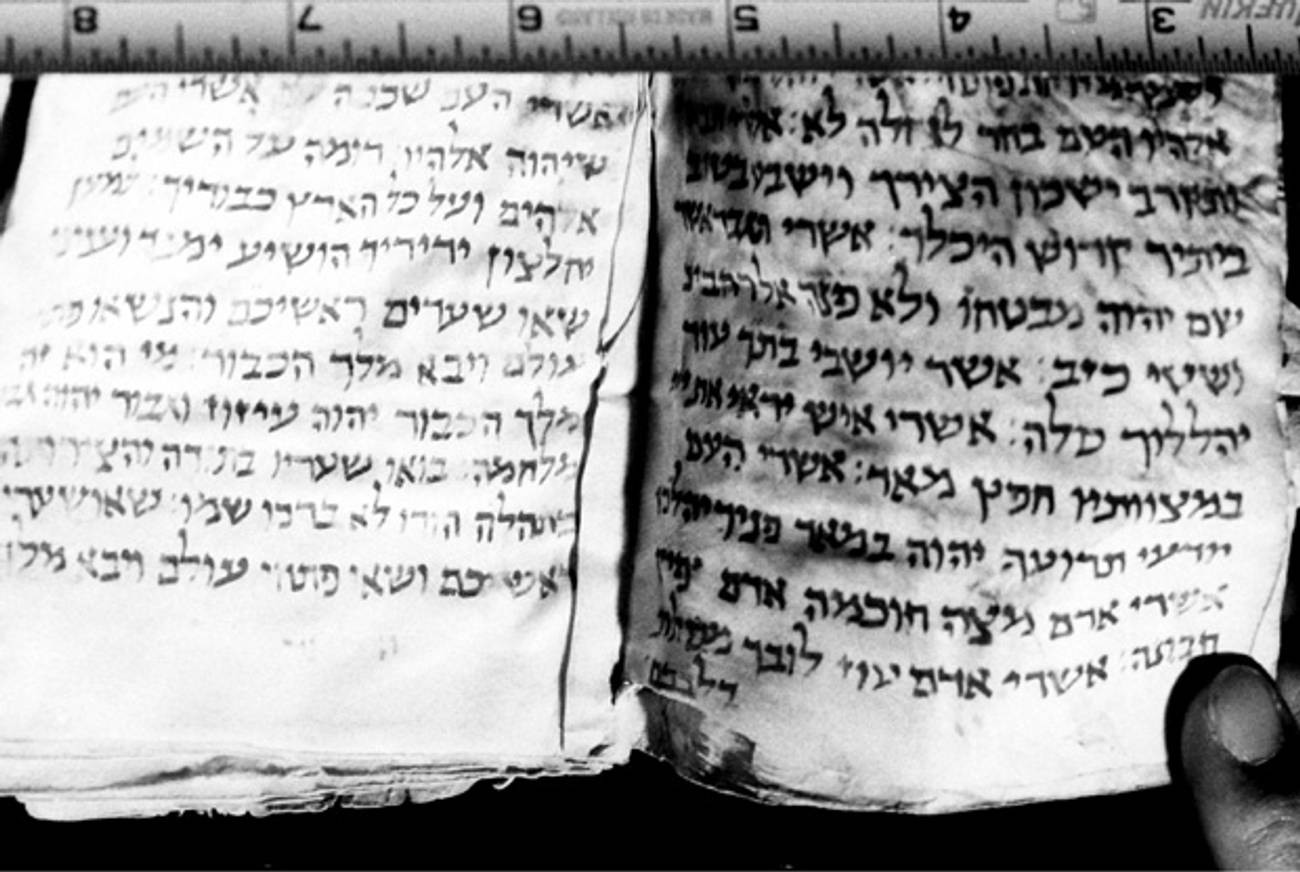

Despite this sad situation, some effort has been made to preserve Afghanistan’s cultural heritage, including the country’s historic Jewish heritage. In 1994, when the Herat museum opened, one exhibit was a Hebrew scroll, presumably part of the Torah. Jewish synagogues in the main cities have been allowed to function with little problem, though today there is just one left. Jewish material also turns up occasionally. In 1997, during a visit to Bamiyan, I was shown a Hebrew Book of Psalms (Tehillim) dating from the 16th or 17th century, though the whereabouts of this manuscript is now unknown.

Little is known about the contents of the new cache of Afghan Jewish documents; the London dealers who are offering them for sale are coy about sharing information. However, according to the Jerusalem Post two Israeli scholars have confirmed their authenticity. The specific provenance of the manuscripts, though, remains a mystery, but the most likely source is the well-documented medieval Jewish community at Jam in the province of Ghur in central Afghanistan. Recently a joint Australian-British archaeological mission to Jam reported that the area of urban occupation around this site had been robbed. Probably pillagers came across the cache of documents, which had been hidden or buried during a time of war.

Press reports claiming the manuscripts were found in a cave by a shepherd can probably be discounted, as this story sounds like a rehashing of the Dead Sea Scrolls discovery. Dealers always give false provenance to smuggled antiquities, while those who do the actual pillaging are equally reluctant to reveal the location of the hoard for fear that competitors might move in. And while Afghanistan’s strict laws on cultural heritage are honored in the breach, they do make pillagers and middle-men nervous. If caught, such individuals face heavy fines and long terms of imprisonment.

The manuscripts in this latest cache are all said to date from the 11th century and indicate the presence of a sizable Karaite community in the country. The documents are written in Judaeo-Persian or Judaeo-Arabic and include an ancient copy of the Book of Jeremiah and a previously unknown work by Rabbi Sa’adia ben Yosef Gaon (892-942), founder of Judaeo-Arabic literature. If this is the case, these works alone are a major discovery. The manuscripts are also said to include lamentation poetry and financial records. The commercial documents could prove to be particularly important as they will hopefully give us more understanding of Jewish trade links and land ownership.

Afghanistan’s Jewish heritage is ancient. When Arab Muslim armies swept into the area in the mid-8th century CE, they encountered a well-established Jewish community known as Jahudan or al-Yahudan al-Kubra, or the Great Jewry, whose inhabitants claimed to be descendants of Jews displaced by the fall of Jerusalem in 597 BCE. The Arabs renamed the town Maimana, or auspicious town, because they believed a place called the Great Jewry was unlucky. Yet despite the Arab renaming of the settlement, local people continued to refer to Maimana by its old name, Jahudan. In the late 10th century CE, a local writer noted that the town “located at the foot of a mountain” was still “prosperous and pleasant.”

Maimana’s Jews were mainly traders, engaged in the transcontinental commerce of the Silk Road, for their town straddled the main caravan route between Herat and Balkh. Maimana also had strong commercial links with Merv, Khiva, and Bukhara, all of which had fairly large Jewish populations. The Jews of Afghanistan were also money-lenders, brokers, and bankers. Maimana today is the capital of Faryab province and is still a sizable if somewhat run-down trading and market town—a convenient stopping point for truck drivers plying the Herat-Balkh road. The Maimana area is one possible source for the newly discovered cache of Jewish manuscripts.

In the late 1950s, a French archaeologist, André Maricq, recorded a previously unpublished 12th-century minaret 65 meters high at Jam in Central Afghanistan. The minaret is dated 1174-5 CE, which placed its foundation in the reign of the Ghurid Sultan, Giyath al-Din (r. 1163-1203 CE), when the town, which at that period was known as Firozkoh, was the summer capital of the Ghurid dynasty. A few years later, Italian conservators working on the minaret came across some 20 Hebrew inscriptions carved on large pebbles about a kilometer from the minaret. The inscriptions were headstones of Jewish graves written in Judaeo-Persian—a mix of Persian and Hebrew that was written in Hebrew script. To date, more than 70 Jewish gravestones have been recorded in the area.

The inscriptions reveal that the Jewish community of Firozkoh was self-governing and had their own courts, judges, and schools. The secular head of the community was called Rosh Kahal while the most senior religious leader held the title of Rosh ha Sadranut, probably a translation of Raish Sidra, a title bestowed on a senior rabbinical judge of the Pubethita school.

Nearly 30 of the headstones bear the title Alut or Aluf, or a rabbinical judge. There were also several Hakham, orreligious teachers. The use of the term Melamed and Rosh Kanisa indicates the community had at least one synagogue, kanisa being Persian for synagogue. Clearly this remote Jewish community was devout and had a number of well-trained religious scholars with links to Iraq. Other members of the community included traders, an accountant, a weaver, and a goldsmith. Oddly, not a single woman’s headstone has been found.

The dates on the headstones range from 1012 to 1220 CE, which suggests that there was a Jewish presence in Firozkoh for over two centuries. Exactly why Jews decided to live in such a remote mountain area, though, is still a mystery. Jam is located near a seasonal trade route between Herat and Kabul that is open from April to October. Maybe the early Jewish settlers lived in Jam during the trading period and moved back to Herat for the winter. By the early 9th century CE, urban Jews and other non-Muslims were living in a society increasingly dominated by Islamic law. The mountain regions of Ghur, on the other hand, were largely un-Islamized; indeed, until the early 11th century the region was the home of a large pagan enclave. Ghur may have offered Jews a chance to live without the restrictive dress and social codes imposed on non-Muslims under Islamic law.

The latest date on the gravestones is 1220 CE, a date that coincided with the Mongol invasions of Balkh; undoubtedly the devastations wrought by the Mongols were the reason for the demise of Jam’s Jewish community. The Mongols systematically destroyed the fortresses that protected Ghur, massacring any garrison that refused to surrender. Those who did capitulate were enslaved, sent to Mongolia, or conscripted into the army. Most of Jam’s population would have fled or been killed or made captive as a result of the Mongol onslaught.

Jewish communities, however, still survived in Afghanistan’s urban centers, and 19th-century European travelers made frequent reference to them. When Arthur Conolly, who was later executed by the Amir of Bukhara, passed through Herat in the 1830s, he was a guest of Rabbi Isma’il and celebrated Sukkot with him. Another visitor at this period was the German Jewish Orientalist Rev. Joseph Wolff. A convert to Christianity, Wolff was a missionary for the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews. His life’s mission was to track down the Lost Tribes of Israel and convince them that Jesus of Nazareth was the messiah. During his travels though Afghanistan, he held debates with the rabbis of Balkh and Kabul.

By the 1830s, life for Afghanistan’s Jews was increasingly difficult. Dynastic wars, conscription, intolerance, extortion, and the collapse of the overland trade led to many Jews quitting Afghanistan for good. By 1886 there were just six Jewish families left in Maimana, though there were still eight synagogues in Herat and four in Balkh. A further exodus took place in the 1930s after the government ordered all Jews living in the north to leave and reside in either Herat, Kandahar, or Kabul. As war in Europe loomed, the Nazis tried to secure Afghanistan as an ally against Britain. Part of their strategy was to flatter the Afghan ruling clique, who were all ethnically Pashtuns, that they were also Aryans and part of the so-called Master Race.

Hitler failed to draw Afghanistan into an alliance with Germany, but Nazi Aryan propaganda became embedded within dynastic and Pashtun nationalist discourse. The royal family, court historians, and some of the Pashtun-dominated intelligentsia were convinced that they were descendants of Aryans. Afghan officials began to claim that Balkh was the ancestral homeland of the Aryans, and Aryana became regarded as synonymous with Afghanistan. The national carrier was named Aryana Airlines, and the official government print house was called Aryana Press.

Inevitably, Afghanistan’s Jews suffered as a result of this Aryan myth, and soon the majority decided they had had enough. Most of Afghanistan’s Jewish population ended up in the Old City of Jerusalem or in New York. Today Afghanistan has only a single indigenous Jew, who is guardian of the Kabul synagogue. The synagogues of Herat, Balkh, Maimana, and elsewhere are now private dwellings, though some traces of Hebrew inscriptions are still visible.

One can only hope that the important documents chronicling a lost Jewish community will end up in a public collection where they can be properly preserved and studied—and eventually returned to Afghanistan.

Jonathan Lee, who has been studying Afghanistan’s history for more than 35 years, is a freelance consultant and writer living in New Zealand. He holds a doctorate in religious studies from the University of Leeds and is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Jonathan Lee, who has been studying Afghanistan’s history for more than 35 years, is a freelance consultant and writer living in New Zealand. He holds a doctorate in religious studies from the University of Leeds and is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.