Whitman and the American Revelation

The epiphany that led to a national literature’s single greatest achievement: tucked in a prosaic, newly discovered early novel are the seeds of ‘Leaves of Grass’

A literary scholar named Zachary Turpin at the University of Houston has discovered and published two previously unknown books by Walt Whitman during the last couple of years, but, like Columbus, he has been reluctant to recognize the implications of what he has found, and his principal commentators, some of them, have displayed the same reluctance, and, as a result, the full significance has not yet emerged. It is an astonishing discovery, though. It throws a brilliant and revealing light on the culture of the United States at its most beautiful and adorable—or, if my enthusiasm is getting out of hand, I would say, at least, that it halfway solves a large and enduring and central mystery of American literature.

Whitman thought of himself as the national poet of the United States, and it is reasonable to conclude that, for a good many people, he is, in fact, the national poet, as shown by an infinity of Walt Whitman High Schools, shopping malls, street names, auditoriums, and housing projects, not to mention what the American poets have felt about him, and the music composers, and even the political philosophers. The biographers and critics have been studying the man for 150 years by now, which adds up to a lot of thinking and research. And, even so, something at the heart of his literary career—his evolution into a major writer—has always resisted explanation.

In his early years, he worked as a freelance journalist and editor for a large number of newspapers and magazines in Brooklyn and New York, cranking out writings of every sort—local-color reports, political commentaries and polemics, book reviews, music reviews, short stories and commercial novels. And all of it demonstrated a talent. The Democratic Party’s literary and intellectual magazine in the 1840s was the Democratic Review, where Hawthorne was the in-house short-story writer, and, when Hawthorne stopped writing stories, the editors replaced him with young Whitman. But no one mistook him for another Hawthorne. His ideas were conventional, his prose sometimes ponderous. His greatest gift was productivity.

And then, without the slightest warning, in 1855, at age 36, he came out with the first, slender edition of Leaves of Grass, which he proposed as a new national document, akin to the Declaration of Independence, except in free verse, with hints of a semi-religion. Nothing that he had ever written could have prepared his readers for such a book. Nor did he seem to be treading in some other writer’s footsteps. Nor did he quote anybody else. His book appeared to be original in every aspect—tone, prosody, larger structure, philosophy—quite as if he were, in his own phrase, a “divine literatus,” conveying more-than-human revelations. But then, since he had never given any indication of supernatural abilities in the past, it was natural to wonder what had happened to him. Emerson himself, in a famous letter to Whitman, wondered about “the long foreground” that must have led to the book. “I rubbed my eyes a little, to see if this sunbeam were no illusion.”

The discoveries that Zachary Turpin has made are newspaper serials from Whitman’s hack-writer days, beginning with a men’s health manual. The manual, called Manly Health and Training, ran under a pen name in a forgotten newspaper called the New York Atlas in 1858—which shows that, even after he had brought into print the first edition of Leaves of Grass, he did need to make a living, and he went on cranking out copy for the commercial press. Manly Health and Training has its charms—it is exuberantly nutty in certain passages—but his purpose in writing it was to fill a maximum number of column-inches and get paid. And his further purpose was to ensure that, afterward, the manual would disappear from memory, which it did. Turpin has deployed the tools of digital research to ferret out its existence, and this is wonderful. We Whitman fans are delighted. But the health manual is not going to change our view of Whitman or of anything else.

Turpin’s more recent discovery, though, is an earlier piece of writing—something from the “long foreground,” and not from after. It is a serialized novel called Life and Adventures of Jack Engel: An Auto-Biography, which ran, unsigned, in six issues of a different forgotten newspaper, the Sunday Dispatch, in 1852, three years before Leaves of Grass. The University of Iowa Press has brought it out as a short book, this time under Whitman’s name with an introduction by Turpin. It has to be conceded that, for most of its pages, Life and Adventures of Jack Engle offers still more evidence that Whitman went about his commercial writings with gusto, relentless in his clichés and pompous good cheer, unerringly melodramatic, sentimental, and predictable.

The virtuous young narrator, Jack, discovers a dark family secret, and a virtuous young Quakeress of his acquaintance discovers a related secret in her own family, which endows her with a fortune. And Jack and the Quakeress get married, although not before Jack takes up for a while with the fiery Inez, the Spanish dancing girl—“Inez, a Spanish dancing girl” is her legal name—and even kisses her. The kissing scene isn’t bad. Villainous lawyers with frightening names conspire to do ill. The prose style is ridiculous. “Even Mr. J. Fitzmore Smytthe came in for his share of the high-strung girl’s displeasure. And, at his next visit, Inez saluted him with such a voluble and fiery tongue, that this genteel and taciturn individual was fain to put his fingers in his ears and beat a retreat in double quick time.”

Still, tucked within the plot are 12 pages that appear to have been inserted almost by mistake—a dozen pages that make it seem as if Whitman, in toiling over his composition, had lost control of the literary discipline that hack-writing requires, and the incubus of authentic inspiration had gotten hold of him, and he did not know what to do, except to go on scribbling demonically, sheaf after sheaf. Here is Turpin’s true discovery—the major find, at least in my interpretation. Life and Adventures of Jack Engle is a New York novel, and the plot requires Jack and the Quakeress and a couple of friends to row a boat across the Hudson River to Hoboken, where Inez the Spanish dancing girl lives. The oars dip into the water, and the rhythms of the prose slow down, and the preposterous diction disappears. “The fresh south breeze came pleasantly up from the Narrows; the water dashed in ripples against our boat.” Sound itself comes to a stop:

Out in the middle of the river, we lay on our oars a few minutes, and enjoyed the scene still more. The long stretch of the city’s shore was silent and hushed; two or three sloops, at various distances on the river, moved along, their white sails showing like great river ghosts; and not a harsh sound was to be heard.

The Hoboken shore, too, was solitary and still. As we neared it, the just-risen moon shone out from a cloud, and scattered a flood of light on the wooded banks, the water, and every thing else.

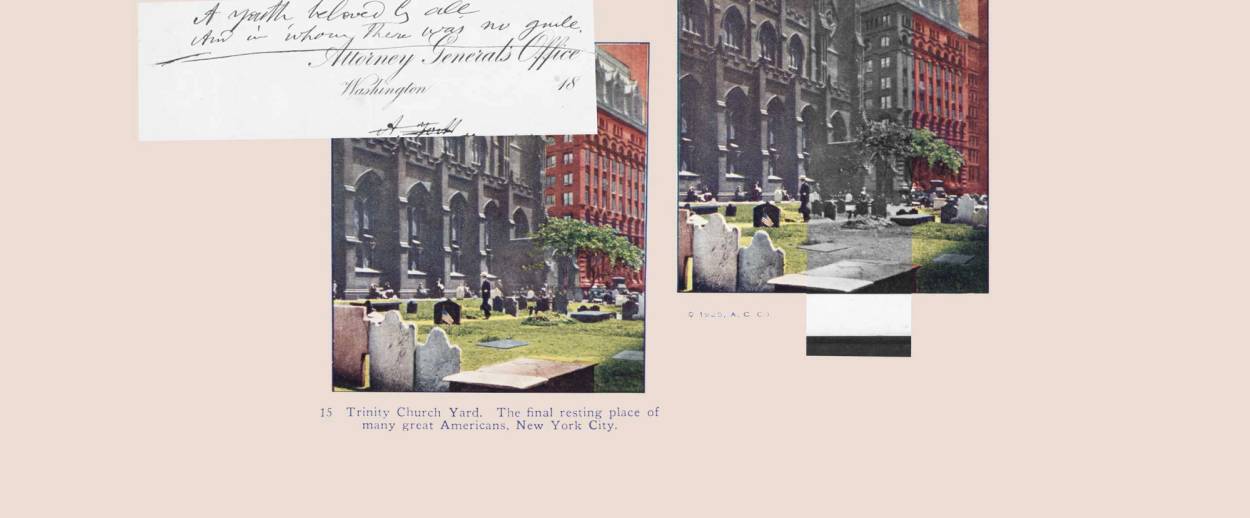

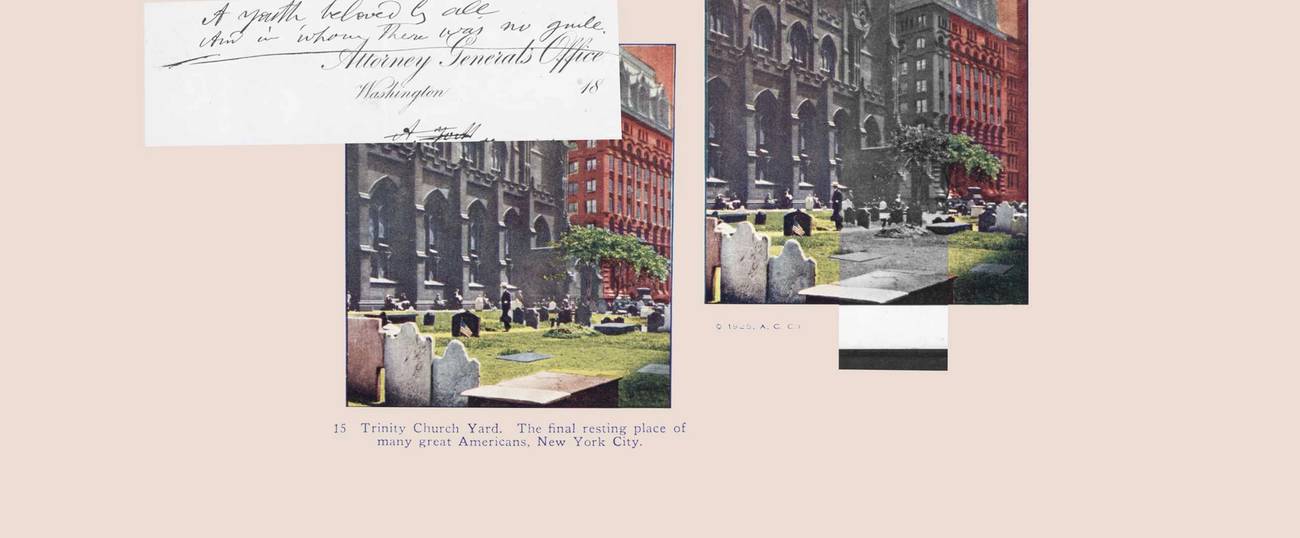

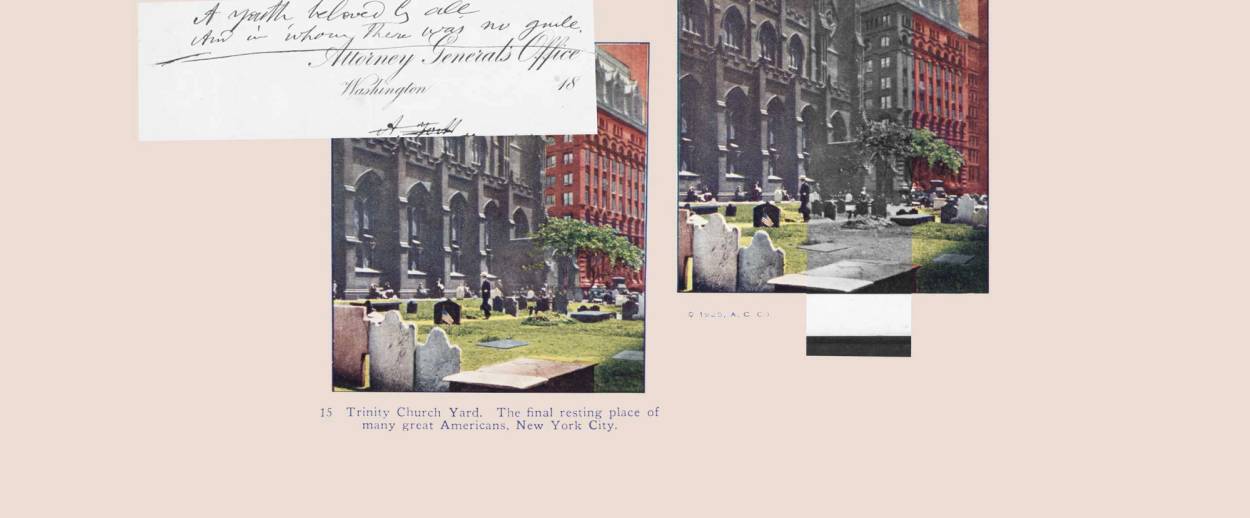

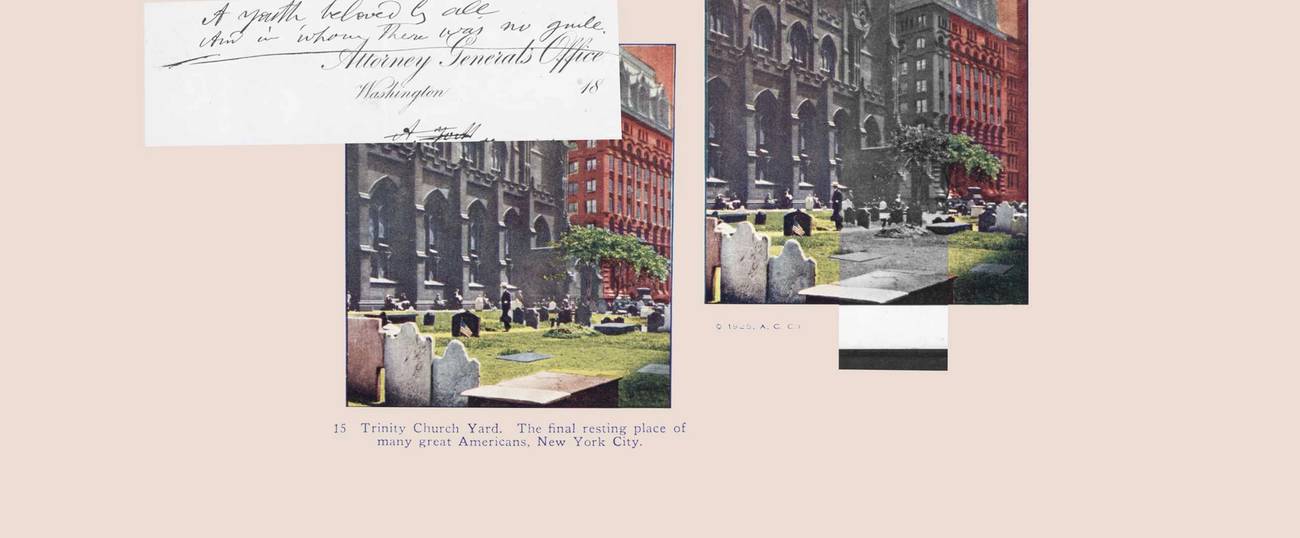

Jack returns to Manhattan and attends a funeral of someone he knew at Trinity Church on Lower Broadway. He lingers after the ceremony.

I spent the rest of that pleasant, golden forenoon, one of the finest days in our American autumn, wandering slowly through the Trinity grave-yard. I felt in the humor, serious without deep sadness, and I went from spot to spot, and sometimes copied the inscriptions. Long, rank grass covered my face. Over me was the verdure, touched with brown, of trees nourished from the decay of the bodies of men.

Turpin in his introduction refrains from remarking on the phrase about grass covering Jack’s face, but other people, in commenting on the novel, have pointed to it, as is only natural. The phrase anticipates the central image in Whitman’s supreme poem, “Song of Myself,” in Leaves of Grass, not to mention the book-title itself. But there is more to those dozen pages than a single haunting image. Jack comes upon the grave of a sailor from the War of 1812. He sits on the grave and thinks about death, and, then again, he thinks about how happy he is with his circle of friends and the people he loves. “I was happy that I lived in this glorious New York, where, if one goes without activity and enjoyment, it must be his own fault in the main.”

His happiness increases:

Truly, life is sweet to the young man.—Such bounding and swelling capacities for joy reside within him, and such ambitious yearnings. Health and unfettered spirits are his staff and mantle. He learns unthinkingly to love—that glorious privilege of youth!

The reverie is physical, and it is easy to imagine that, whatever has prompted Jack to sit on the gravestone, he has continued sitting there in order to prevent his bounding and swelling capacities for joy and love from becoming visible.

He inspects other gravestones and the inscriptions lead him to reflect that people who were born in New York have ended up returning to Trinity Church to be buried. This observation sends his prose into still another register, and out surges a tone whose inspiration is the Bible, with a bird as theme.

Human souls are as the dove, which went forth from the ark, and wandered far, and would repose herself at last on no spot save that whence she started. To what purpose has nature given men this instinct to die where they were born? Exists there some subtle sympathy between the thousand mental and physical essences which make up a human being, and the sources where from they are derived?

A date from long ago on one of the tombstones leads him to contemplate America’s history. “What great events have happened too, since that time! A nation of freemen has arisen, outstripping all ever before known in happiness, good government, and real grandeur.” He reflects that not everything has been marvelous in America’s development. He comes upon the gravestone of Alexander Hamilton—“who, in his time, was the sower of seeds that have brought forth good and evil.” Whitman was a solid Jacksonian and a radical democrat, and he means that Hamilton, who brought forth good by helping to establish the United States, also tried to saddle a moneyed aristocracy on the new republic. Another gravestone from the War of 1812 draws his attention. His thoughts return to the heroic young men of the American military.

The time comes to leave the cemetery.

I put my pencil and the slip of paper on which I had been copying, in my pocket, and took one slow and last look around, ere I went forth again into the city, and to resume my interest in affairs that lately so crowded upon me.

Out there in the fashionable thoroughfare, how bustling was life, and how jauntily it wandered close along the side of those warnings of its inevitable end. How gay that throng along the walk! Light laughs come from them, and jolly talk—those groups of well-dressed young men—those merry boys returning from school—clerks going home from their labors—and many a form, too, of female grace and elegance.

Could it be that coffins, six feet below where I stood, enclosed the ashes of like young men, whose vestments, during life, had engrossed the same anxious care—and schoolboys and beautiful women; for they too were buried here, as well as the aged and infirm.

But onward rolled the broad, bright current, and troubled themselves not yet with gloomy thoughts; and that showed more philosophy in them perhaps than such sentimental meditations as any the reader has been perusing.

That last phrase—about sentimental meditations and the reader—leads me to suppose that, having scribbled his several pages, Whitman found himself suddenly recalling that, at the Sunday Dispatch, the editors did want to please the public, and he ought to pull himself together and attend to his plot. Or perhaps he was embarrassed at the unexpectedly cavernous sound of his own voice.

It is unquestionable, in any case, that over the course of those dozen pages, and not just in the single phrase about grass, he had somehow sketched out whole portions of what would become, three years later, the first edition of Leaves of Grass, together with hints of later editions. Here, in the passage about traversing the river, together with the cemetery passages, is an early hint of “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” about traversing a river into Manhattan (though in Leaves of Grass it is a different river) and thinking about the dead. The grass brushing against his face brings us into the reflections on death and life in “Song of Myself.” The sexual sensation in the cemetery is “Song of Myself” precisely, with its cosmic blow-job, or what appears to be a blow-job, at the mystical and ecstatic highpoint of the poem. The bounding and swelling hint of the “Calamus” poems. The meditations on dead soldiers and sailors: this is the grand theme of any number of additional poems, notably in the editions of Leaves of Grass from the Civil War years and afterward. The reflections on America and its democratic achievements and the retrograde role played by people like Alexander Hamilton: this is nearly the entire political content of Leaves of Grass. The veering into Biblical exaltation: this is the main principle of his astounding prosody. The invocation of a dove hints of the seagulls in “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking” or the caroling thrush in the poem about President Lincoln. The vista of cheerful crowds on the Manhattan thoroughfare and of coffins underneath: this hints of “Broadway Pageant” and any number of poems of city life, with their metaphysical contrasts, the present and the eternal.

Why did he gather those many poetic hints and suggestions into the dozen pages and plunk them into the middle of his silly novel? I can only offer a writer’s intuition on this point. I think he wrote those pages because everything he describes happened to him in real life, in one fashion or another, during the period in 1852 when he was working on the novel. I think he crossed one of the rivers surrounding Manhattan, and found himself in a thoughtful mood. I think he wandered around the Trinity cemetery and bent down to read an inscription, and grass brushed against his face, which led him to reflect that he had come into physical contact with life and death at the same time. The physicality of his thoughts led him to reflect on the joys of life, and not just on the sorrows, and he was unafraid to recognize that, however inappropriate it might be, a sexual sensation was among his responses. His patriotic heart pounded at the grandeur of American history and of democracy. And he wandered from the cemetery out to Broadway and pursued his thoughts about death and life, and meanwhile noticed how smartly everyone was dressed. The detail about putting away the pencil and slip of paper catches my eye. Jack, the narrator of the novel, has no reason to be carrying a pencil and paper wherever he goes, but Whitman, the real-life scribbler for the newspapers and magazines, would naturally have kept his pockets fully stocked.

I think he wrote those dozen those pages because his day’s experience struck him forcefully and he wanted to record them. He inserted the pages into Jack Engle, even if they did nothing to advance his plot, because the Sunday Dispatch paid him by the column inch, probably. And he had not yet realized how valuable, how sacred, how spectacular, were those few pages—how significant they would be for his own development. Or he halfway realized, but not entirely. I wonder how he felt when he finally got his hands on the printed newspaper. The shift into a Biblical tone for a line or two—did that strike him as a mistake, when his eye fell across it? Or did the cavernous sound strike him, on second thought, as altogether thrilling? He had never considered himself a poet in the past—or, at least, he is not known to have done so. Did he recognize, glancing at the Sunday Dispatch, that Biblical inspirations could bring him into the a zone of poetry unlike anything that other poets were writing? Did he realize that, in those dozen pages, he had come up with themes for a lifetime, and his many themes added up to a single theme, which had to do with life and death and America and eternity and a limited number of strangely-related images, the river, Manhattan, the dead beneath the soil, the grass, the bird, the dead soldiers? I think that in some dim fashion he did realize it.

I do not mean to suggest that, in those dozen pages, the whole of the inspiration for Leaves of Grass suddenly appeared. A principal element was still missing, and this was the concept of the author. The narrator of Life and Adventures of Jack Engle is Jack at age 22—a simple young man with a knock-about past in the New York streets. To transform those dozen pages into Leaves of Grass, Whitman had to get rid of Jack. He had to replace him with “Walt Whitman, a kosmos, of Manhattan the son”—which is to say, had to come up with a concept of himself as someone like Jack, except with supernatural aspects, a mortal with qualities of an immortal. His ego had to expand accordingly. He needed to undergo a further moment of inspiration, then—a moment when he came up with the cosmic sense of himself and began to feel comfortable with it. When did this other moment occur? I deduce a possibility. The second moment took place when he contemplated the written image of the grass brushing against his face, and he realized, as he probably did not when he first scribbled the image on a sheet of paper, that his unitary experience of life and death conferred on him a more than mortal quality. He needed only the courage to announce his own capacity to speak for the eternal, which meant death, and the voice that would allow him to do so. But he was already speaking in the voice of eternity, audible in the sentence about the dove and the ark.

The reviewer of Life and Adventures of Jack Engle in The New York Times Book Review a few weeks ago was Ted Genoways, who has written a book about Whitman in the Civil War. Genoways takes the position that Whitman’s intellectual evolution was gradual. “Whitman did not one day set aside the hack journalism and cheap fictions of his journeyman years in favor of a brand new idiom for our American literature.” Leaves of Grass, in Genoways’ view, was “not the result of a single flash of revelation.” He writes: “There are no grand epiphanies, no sudden transformations in American literature, any more than there are in American life.” But I think that, in those dozen pages in Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, we see the opposite. I think there was, in fact, a grand and sudden epiphany. I think the epiphany came to Whitman on a day when he happened to cross one of the rivers and visited the cemetery and wandered out to Broadway. Or, half of the epiphany came to him on that day, and later would come the rest of it, which led him to declare himself a kosmos. I cannot imagine anything else, when I read those pages.

I think that Leaves of Grass is American literature’s single greatest achievement, the greatest expression of the American idea and the democratic idea ever written—an immense achievement, which, if it did not exist, would have left America and the democratic idea thinner and weaker. And the achievement flowed from the epiphany. It was not an evolution. Moments of epiphany do, in fact, occur in American life. That is the discovery. It is true that Whitman had prepared himself over the years to experience his epiphany. He had attended Quaker services (and Methodist services, too, as is suggested in Life and Adventures of Jack Engle), he had studied literature and political philosophy, he had read Emerson, he had listened to Italian opera, he had experimented with writing all kinds of things, as his freelance assignments permitted. In those ways he acquired his education gradually, as everybody does. But the vision that led to Leaves of Grass did not come to him gradually. His transformation was sudden, and the record of it is the 12 pages that contain a significant portion of his poetic inspiration, if only in hints. But the hints are remarkably dense and concentrated.

One other aspect of Life and Adventures of Jack Engle merits an observation—something minuscule, not at all comparable to those dozen pages. I am embarrassed almost to bring it up in the context of his epiphany, but it is worthy of mention at least here, in the electronic pages of Tablet. This has to do with the Jews. New York’s population and economy and geography expanded enormously in the mid-19th century, and a substantial Jewish immigration figured in the expansion—a flood of political refugees from Germany after the failure of the republican revolution of 1848, and from the Slavic countries and elsewhere. Today we can look back and notice that here was the beginning of the mass and historic Jewish flight from almost everywhere in the Old World, which wended at first principally to the United States, and later to Palestine. But none of this attracted Whitman’s attention. Somewhere in his newspaper sketches of Broadway life he mentions in passing a German Jew with a funny accent, perhaps Yiddish, on the sidewalk. One of the poems in the second edition of Leaves of Grass, from 1856, is “Salut au Monde!,” which begins, “O take my hand Walt Whitman!” and goes on to tour the world, with the cosmic Walt celebrating and saluting every conceivable variation of mankind. “You whoever you are!”—which is Whitman at his most lovable. A “Hebrew reading his records and psalms” figures among the whoevers. “You Jew journeying in your old age through every risk to stand once on Syrian ground!/ You other Jews waiting in all your lands for your messiah!” Everybody gets the same salute. But that was all he had to say on Jewish themes, so far as I can recall.

In Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, though, he came up with a wealthy lady, the hook-nosed Madame Seligny, and her black-eyed daughter, Rachel, “a pretty good specimen of Israelitish beauty” with a “national fondness for jewelry.” Madame Seligny is in cahoots with a dastardly lawyer, and, together with her daughter, she runs a house of questionable repute, which sounds bad, in regard to the beauteous Rachel. But not to worry: the house turns out to be merely a place for gambling, and Rachel’s virtue is intact and, indeed, Rachel turns out to be a nice girl, after all. One of Jack’s friends begins to court her. We live in a witch-hunting era, and sooner or later some professor is going to unmask poor Whitman as a terrible anti-Semite because of those scenes and Madame Seligny’s nose. But Whitman has merely scooped up a variety of stock images and characters from French novels and has set them in New York for the purpose of adding flashy allures to his cheap novel, and for no other purpose.

Really Jack Engle is nothing much, apart from the dozen pages. The Iowa edition is handsomely designed, but it is almost a mistake to have presented the book under the majestic byline “Walt Whitman.” It might have been better to publish the novel under the byline that Whitman himself used in those days, when he was in the mood to ascribe something to his own pen, which was “Walter Whitman”—the actual name of an actual journalist, who was less than a kosmos. But then, the cheap and commercial quality of Jack Engle only makes more dramatic, by force of contrast, the dozen pages about the river and the cemetery and Broadway—the pages that appear to record the central moment in the history of American literature, when Walter, the unremarkable journalist, began to undergo the metamorphosis into Walt, a genius.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.