Who by What?

Bob Dylan, Jeff Buckley, Leonard Cohen, U’netaneh Tokef: On Yom Kippur, finding redemption is a matter of laying down the right soundtrack

Who shall live and who shall die,

Who shall reach the end of his days and who shall not,

Who shall perish by water and who by fire,

Who by sword and who by wild beast,

Who by famine and who by thirst,

Who by earthquake and who by plague,

Who by strangulation and who by stoning,

Who shall have rest and who shall wander,

Who shall be at peace and who shall be pursued,

Who shall be at rest and who shall be tormented,

Who shall be exalted and who shall be brought low,

Who shall become rich and who shall be impoverished.

—“U’Netaneh Tokef,” by Amnon of Mainz

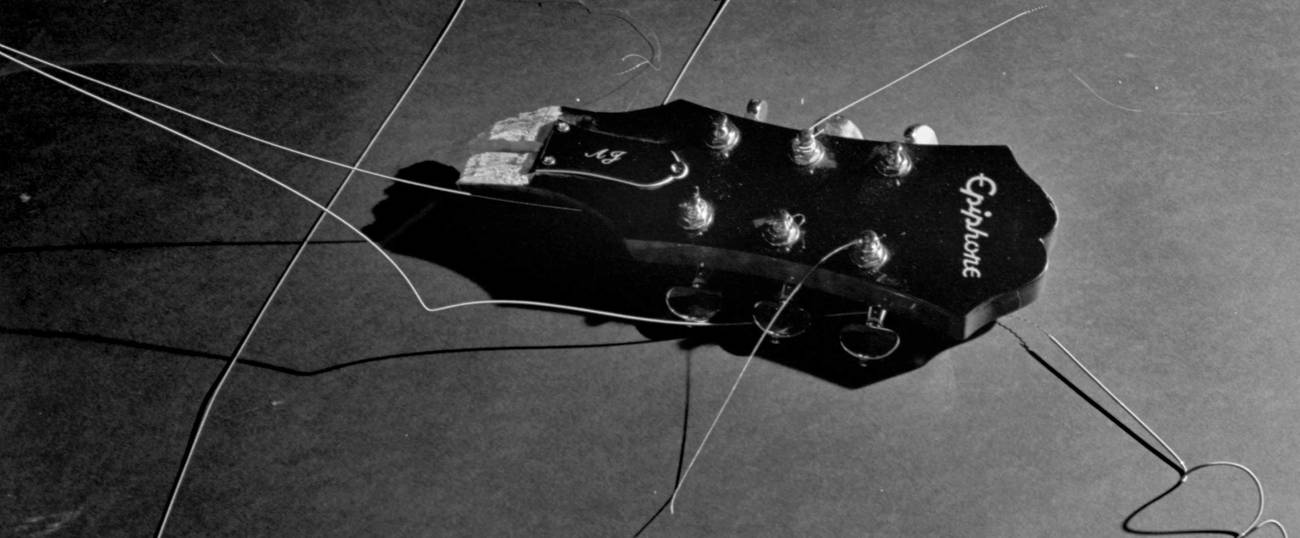

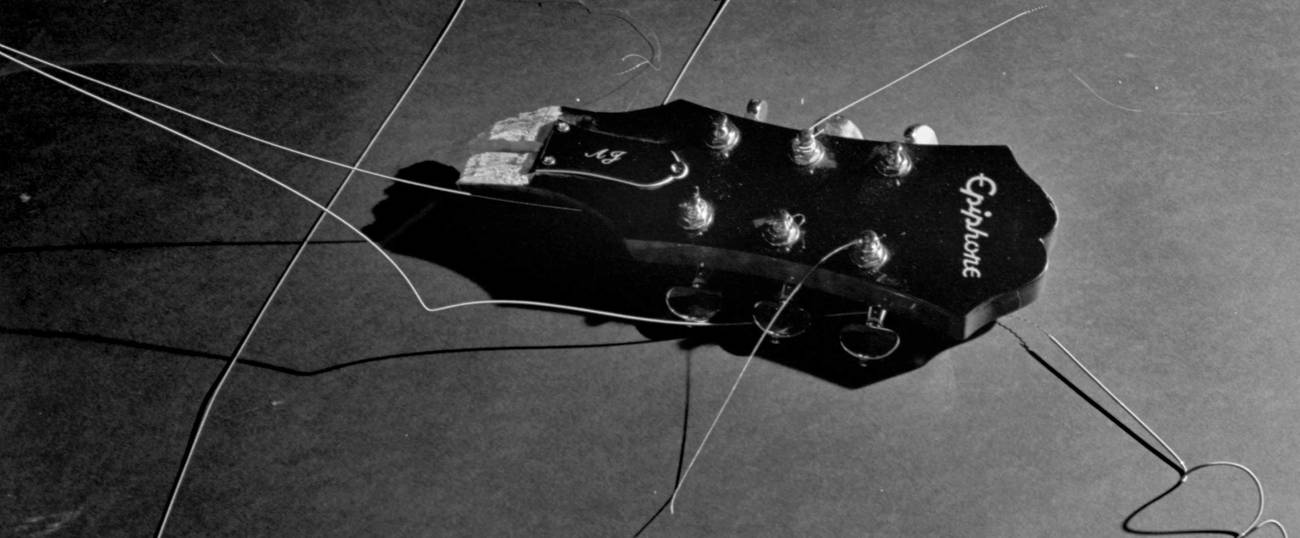

For a while I preferred Jeff Buckley’s version of “Hallelujah,” which, like many covers, was strangely more authentic when not performed by the composer who created it, to the one Leonard Cohen himself recorded with all its production and flourish. I used to go see Jeff sing at Sin-é on St Marks Place in Manhattan sometimes, at least two decades ago, and his falsetto and acoustic guitar were a much better weapon against love and God above. And I remember when people like Tommy Mottola from Columbia Records and Clive Davis from Arista started showing up in their black Town Cars that would sit double-parked on the narrow streets outside, these guys would be taking up so much space in this small room, everyone was so skinny and grungy and they were big and fat in their pinstripe suits, and soon enough—soon enough: Who shall perish by water? Jeff drowned while recording in Muscle Shoals.

And I realized I liked the Cohen version of “Hallelujah” better than the gazillion others because it of course sounded like the High Holy Days, like an authentic attempt to connect with a time when God was real to me and maybe to Cohen too—to age 7 or so. The big bombastic chorus was most authentically shul-like. Not temple-like or even synagogue-like: I had it right the first time. That song is to Judaism what “Like a Prayer” is to Catholicism: It’s the heavenly sound of sin. And “Who by Fire” is Cohen’s rendering of Amnon of Mainz in a hipster beret with every possible way to die—it’s like the cumulative opening scenes of Six Feet Under in a song: Who by autoerotic asphyxiation? Who by driver in next car text-messaging? Who by mob hit?

OK, I lied. Leonard Cohen is not so graphic. And he’s deep. (What I really think is that he’s, like, deep) Like this: “Who by avalanche?/ Who by powder?/ Who for his greed?/ Who for his hunger?” He does not seem like a guy with a sense of humor.

I have always thought of Leonard Cohen as the Jewish Bob Dylan. Know what I mean? Cohen is Robert Zimmerman on the road not taken, or maybe he stopped short at the fork and thought: Fuck it, I’m literary, I’m allegorical, I’m liturgical, and folk music is not for me. I see Cohen as Robert Zimmerman with a different affect, what he would have been like if the coffeehouse scene and all those puritanical god-fearing peace-loving frizzy-haired farmers’ daughters and college coeds on Fourth Street had made him just a little more nauseated, if Dylan had gone urbane.

All of which is to say that unlike everyone I know, I am not a huge Leonard Cohen fan. Nothing against him, nothing for him, just not my thing. Deep down, I’m sincere. Actually, on the surface and in the middle, I’m sincere. That is not a Leonard Cohen emotion. Dylan is either downright mean or totally sweet, but Cohen is just embarrassed about getting caught with a soft spot for some girl—he’s the guy who is mesmerized at the sight of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” and cries through the hill-of-beans speech at the end of Casablanca but walks around sneering and hissing so no one will know he has half a heart. He can never leave a tender moment alone: He can’t ask if someone truly cares for music without throwing in his sarcastic “Do ya?” And he cannot remind us that love is an incurable malady without saying of any elixir that “it’s all been cut with stuff,” like we couldn’t handle an uncut and overwhelming thought that heartbreak is unbearable. He cannot even report that the Grim Reaper has arrived—and may do so in many miserable ways—without reducing it to a joke, to a secretary passing the awful news of imminent death on to her bossy boss: “And who shall I say is calling?”

Where Bob Dylan is consumed with nastiness, can compose entire songs that are pretty much about what a drag it is to be with someone or anyone or everyone, Leonard Cohen likes the small jab. He’s the annoying elbow; Dylan will just tell you he needs the entire row or car or airplane or world to himself. Hence a cult following versus one of the most significant singers or songwriters or cultural figures ever.

Also: In the movie Martin Scorsese made about Dylan, No Direction Home, in all 10 hours of it, not once does it mention that he’s Jewish. And kind of the way the lack of a single female character in Lawrence of Arabia makes you notice that there is something sort of girly about Peter O’Toole, Dylan seems Talmudic and rabbinical in that epic filmic study.

Oh, but so what? The point of all this was really to say something about music and redemption, because it’s about to be Yom Kippur. I can’t stand synagogue, but I like prayer and repentance and tossing—perhaps even throwing—my sins away. I like the harshness and intensity that would ideally accompany all this atonement activity, and it makes me sad to realize that those of us who most need to connect with a big idea—like God—are the least likely to be able to manage it. God’s presence is inversely proportional to his necessity, it always seems. Complicated crazy people will tell you they believe in God, but they are usually hedging. Like, see you in heaven if you make the list.

Dr. Gregory House put it most succinctly: There can’t be an afterlife, because that means that all this is only a test.

I cannot figure out how it is that in a world that is devoid of divinity, and in which science didn’t even become spiritual until the theory of relativity, it took us so damn long to invent rock ’n’ roll, which is the way the faithless find their way into something like belief and meaning and hope. And there is no way that Vivaldi or Beethoven could have done in hours for anyone what “Rock Around the Clock” at long last did for everyone in 1956.

So, humanity had to starve for a very long time before that. The closest thing I have experienced to the exhilaration of the first time I heard “Mystery Train” is reading the poetry of the obviously deranged Yehuda Halevi. And by way of wishing one and all an easy fast, I offer you his words, in “The Home of Love,” and wish you redemption, that you may live to sin again:

Ever since You were the home of love for me, my love has lived where You have lived. Because of You, I have delighted in the wrath of my enemies; let them be, let them torment the one whom You tormented. It was from You that they learned their wrath, and I love them, for they hound the wounded one whom You struck down. Ever since You despised me, I have despised myself, for I will not honour what You despise. So be it, until Your anger has passed, and again You will redeem Your own possession, which You once redeemed.

Elizabeth Wurtzel, the author of Prozac Nation, Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women, The Secret of Life, and More, Now, Again, is Tablet Magazine’s pop music critic.