Who Owns Israel’s History?

A former state archivist on the dispute over the first draft of the Declaration of Independence

Who owns the record of a nation’s history? The Israeli Supreme Court recently attempted an answer to that question, in its decision on a case that began on the first day of Passover in April 1948, when 31-year-old Mordechai Beham burst into tears at the family dining table. Two days earlier he’d been tasked with drafting a declaration of independence for the imminent Jewish state, but he had no idea how to start.

As the end of the British Mandate on May 15 loomed, the Jewish leadership within the Palestine Mandate had a fateful decision to make: A declaration of independence would trigger a combined Arab invasion, bloodshed, and possible mass destruction. On the chance that the massive international pressure to wait would be resisted, Felix Rosenblueth (later Pinchas Rosen) was told to set up a future Ministry of Justice. He recruited two attorneys, Uri Yadin and Mordechai Beham. He told Beham to prepare the draft of Israel’s Declaration of Independence on what was more or less their second day at work.

What do you say to someone cracking under the pressure of writing one of the most important documents in your people’s history? “Go talk to Rabbi Davidowitz.” A Lithuanian-born Jew, Harry Solomon, known as Shalom Tzvi Davidowitz, had spent almost two decades as a Conservative Rabbi in the United States before moving to Tel Aviv in 1934 where he ran a dental factory and translated Shakespeare’s plays into Hebrew. Davidowitz lived nearby, and had a large library. So Beham went over to Davidowitz’s house, and they talked.

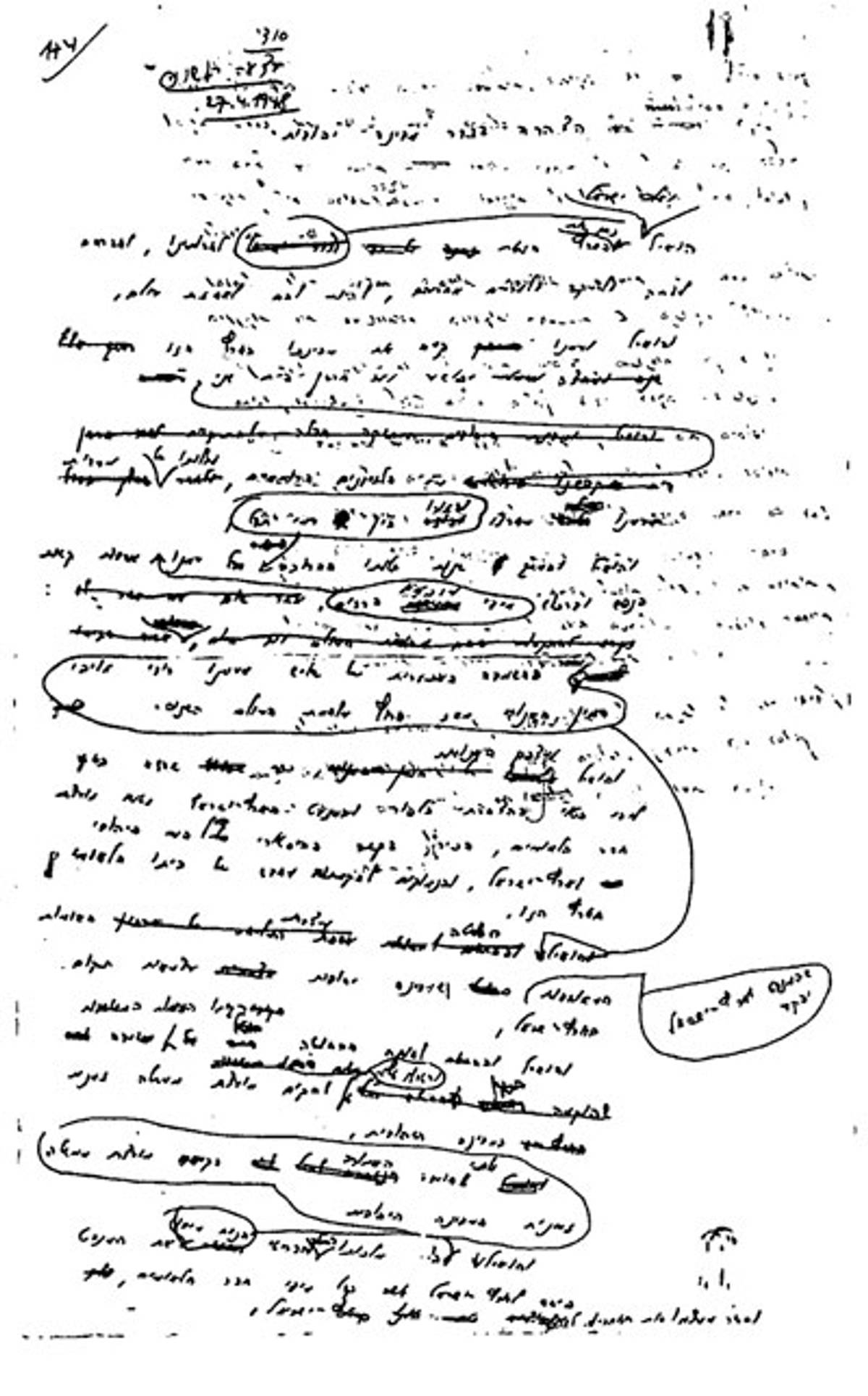

At some point, the young attorney started jotting down notes. First, a page of quotations from famous documents, such as, “When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another …” And also, “Behold, I have set the land before you, go in and possess the land the Lord sware unto your fathers” (Deuteronomy 1:8). Having written down four or five quotations, all in English, he then took another sheet of paper and wrote a first outline of a “Declaration of a Jewish State,” still in English. On a third sheet of paper, he then translated what he had written into Hebrew.

On Sunday, April 25, Beham showed his draft to Yadin. They made numerous editorial corrections. Two days later there was a typed version, thanks to Mrs. Levy, the office secretary. Beham then wrote out a one-page description of what they were trying to do. By the time the draft moved on to other potential authors, he had authored a total of five sheets of paper.

The three weeks between Passover and the declaration of independence were frantic and chaotic—and by any measure, historic. As the fate of nations hung in the balance, any number of officials, politicians, and wordsmiths of varying talent had their turn at formulating the emerging declaration. Along the way someone decided the new country would be called “Israel,” so that name was inserted.

In the wee hours of May 13, a committee narrowly decided to declare independence in spite of everything. Late the next night Moshe Sharrett delivered the final draft of Israel’s Declaration of Independence to David Ben-Gurion, who didn’t like it—and spent the night rewriting it. Two hours before the declaration was proclaimed, he read his version to the men who were about to become Israel’s first provisional parliament. They disagreed with some of the wording, which was revised.

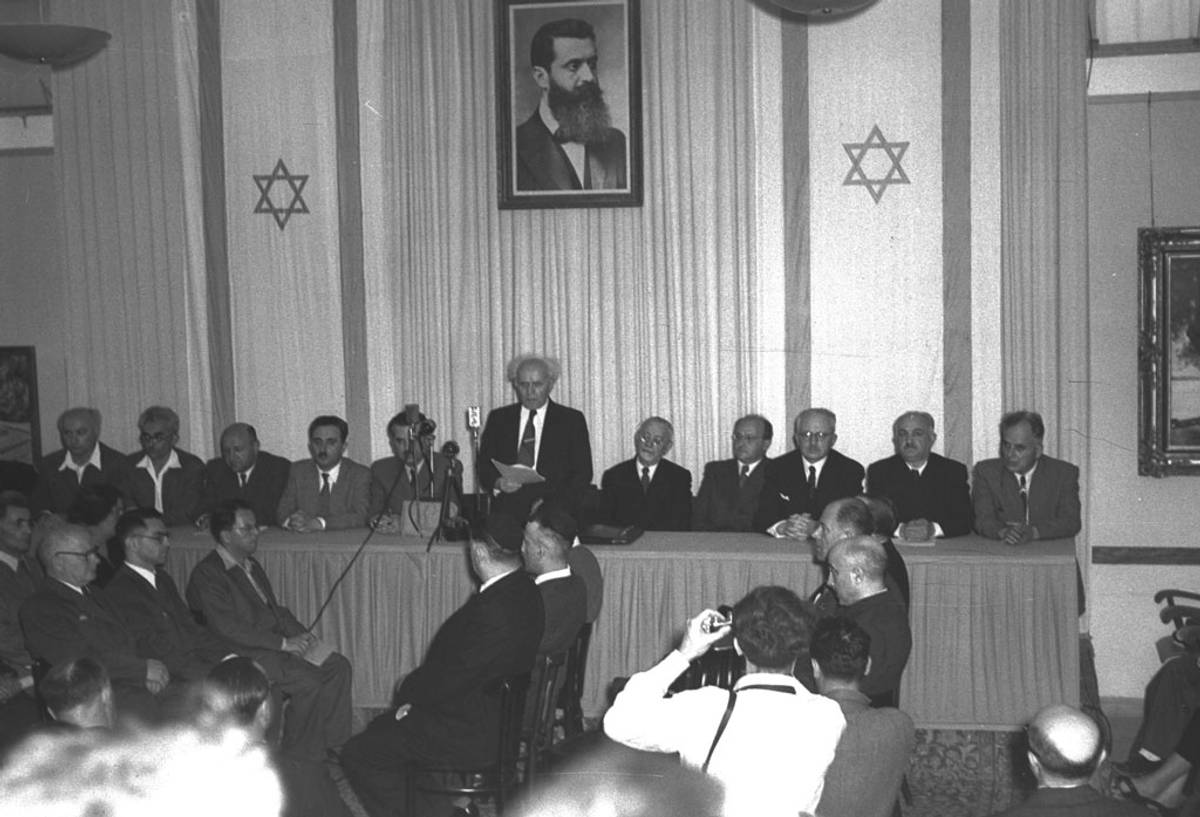

The British Mandate was to terminate at midnight of May 14-15, between Friday and Saturday. Israel’s first sovereign act was to respect the Sabbath and proclaim independence in a secret ceremony on Friday afternoon. The secret was so well kept that large crowds gathered in front of the Tel Aviv museum where it was scheduled.

Ben-Gurion’s car arrived at 4 p.m. and he saluted the policeman at the entrance. Since the wording of the declaration had only been finalized an hour earlier, he read from typed sheets. The 25 signatories put their names on an empty piece of parchment, which was later attached by the calligrapher to the official copy of the declaration. Twelve other members, most of them stuck in besieged Jerusalem, added their signatures later; their colleagues had left space for their names, in alphabetical order.

There’s no reason to assume that Ben-Gurion or any of his colleagues knew of the existence of Mordechai Beham, or that he’d written the first draft of what they’d signed. Decades later, when Uri Yadin’s diary was posthumously published, it transpired that he—and probably Beham—thought the final wording wasn’t very good. And that’s where things would probably have rested had it not been for Yoram Shachar, a law professor, who in the late 1990s thought it would be interesting to know how the declaration, by now the fundamental document of Israel’s liberal democracy, came to say what it says:

THE STATE OF ISRAEL will be open for Jewish immigration and for the Ingathering of the Exiles; it will foster the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants; it will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and it will be faithful to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

Shachar uncovered Beham’s role and went to visit his widow; it turned out that she still had the papers in a box. One of her granddaughters had once shown them at school; I suspect the teacher hadn’t believed her.

In 2002 Shachar published his findings in a fascinating 78-page article, which also had a modified English version of the text—Jefferson Goes East: The American Origins of the Israeli Declaration of Independence. He had two interesting comments on Beham. First, although next to none of Beham’s original words made their way all the way through the process into the final text, its structure did. Beham had decided the declaration should have two segments, one presenting the history of the Jews, the second building upon it to proclaim future intents. Everyone who came after him worked within that structure. Had Beham chosen a reasonable alternative structure, we’d take it equally for granted.

Beham’s second contribution was about God, which is ironic given he was so unfamiliar with tradition that he used biblical quotations from an English-language Bible. The final sentence of the declaration starts with “Placing our trust in the ‘Rock of Israel’, we affix our signatures to this proclamation.”

While the State Archives amassed hundreds of millions of documents, many key players in the country’s history kept important state papers for themselves.

Generations of Israeli schoolchildren, myself included, learn that Rock of Israel—Tzur Yisrael—was the result of a political compromise. The religious Zionists insisted God be in the declaration, the atheists insisted he not be, and so the vague and esoteric Tzur Yisrael was chosen. Well—no, says Shachar. Tzur Yisrael was there from the very beginning, in the very first draft. Most likely it was suggested by Rabbi Davidowitz, who was the kind of person who might have foreseen the heated arguments about God’s role in Zionism, and cannily suggested a formulation that survived all the redrafts.

Shachar’s articles eventually propelled Beham to public prominence. The family now knew and could demonstrate that their documents were valuable. In 2015 they attempted to sell them, through an auction house. This brought them to the attention of the authorities, none of whom had read Shachar’s article. The authorities—as the state archivist I was one of them—asked themselves if a private family could sell such important documents, and didn’t they actually belong to the nation?

***

Beham didn’t see anything wrong with keeping the five pieces of paper he had authored. The State Archives was only founded a year later, and the law defining its role and position in society was legislated only in 1955. Then, and for decades thereafter, figures of far greater historical significance than he took home files when they left jobs. The single most famous filcher of documents in Israeli history was Ariel Sharon, who took truckloads. But any number of famous Israeli officials or politicians you can name did the same (Moshe Dayan proudly and publicly specialized in looted archeological items). Nor did the tradition die out: There were important people who were still hoarding documents of their tenure quite recently; if the practice has subsided, it’s mostly because no one writes on paper anymore.

Moreover, the law of archives itself takes at best a hesitant and oblique position on the requirement that government papers remain in public possession by being deposited in the archives. This may have to do with the fact that the original professional field of Israel’s archives was peopled entirely by immigrants from German-speaking lands, derisively called yekkes by the dominant Eastern Europeans. Even when the yekke archivists managed to convince the Knesset to legislate them a law, other Israelis were wary of giving them any additional authority.

So while the State Archives amassed hundreds of millions of documents, many key players in the country’s history kept important state papers for themselves.

Eventually, a special division in the Prime Minister’s Office was created to fund heritage preservation projects. A dramatic makeover of the National Library was launched, followed by major reforms at the State Archives. Archivists began talking about retrieving lost archival collections; an early accomplishment was the signing of an agreement with the Sharon family.

Then the Beham papers came onto the market. The case was hardly clear-cut. One phone call I took was from Zvi Hauser, former secretary of the cabinet (and now a newly elected MK). “Yaacov, I understand your hesitation. You’re right the state is likely to lose this case. But that’s the point: You need to lose spectacularly, so the Knesset takes notice and changes the law.”

In a packed meeting late one evening at the Ministry of Justice it was decided that drafts of the Declaration of Independence belonged to the nation, not to individuals. We went to court to demand they be deposited in the archives. The media followed the story throughout.

If I’d expected the trial to revolve around the role of the archives in preserving national memory, I was wrong. The District Court in Jerusalem was displeased we’d waited almost 70 years, and focused on property laws. There was much discussion of Beham’s contractual status during those chaotic few days when the existence of the country was still being debated. Beham’s family told of the drama over that weekend—the operative words of their presentation being “family” and “weekend,” both of which are sacred to modern-day Israelis. We had hoped the case would be easy—it was the Declaration of Independence, for crying out loud!—but it wasn’t.

In 2017, the court ruled against us. When the same auction house then announced it had the June 1967 telegram announcing the conquering of Sinai, as well as files of military documents from the 1950s, the state litigators warned us they needed rock-solid evidence, or else they wouldn’t represent us.

Then in May 2019 the Supreme Court reversed the original Beham decision. Beham may have been at the family dinner table, but the reason he was so agitated was the result of his job—and in some circumstances, the nation’s claims to parts of its heritage that are stronger than those of the individual who possesses them. The documents would be deposited in the State Archives.

By the time of the final decision I was no longer state archivist. Looking back, I’m not quite sure that the decision in our favor was the right one. The Beham family weren’t out to get rich. There were unfortunate circumstances in which they needed the money; on our side we had deep pockets and the state apparatus. There was a whiff of bullying in our position, especially in our decision to launch a precedent-making case against an unknown family—and not, say, against some formerly powerful and still well-connected politician.

Perhaps we could have agreed the archives would get top-quality scans, and the family would have committed to selling, on the condition that the documents stayed in Israel? Might it have been possible to find a donor to purchase the documents without an auction and deposit them in the archives? We didn’t explore these avenues.

My main qualm, however, is with an unspoken assumption underpinning the Supreme Court’s decision: that the State Archives represents the citizenry, and operates to the best benefit of the national community. For that argument to be compelling, the archives would have to truly operate as the proxy of the citizenry, and it would have to be as broadly accessible to everyone as possible. Sadly, this is only partially so. Much of what’s in the archives is not open to the public.

But that’s a story for another day.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Yaacov Lozowick teaches at Bar Ilan University. He is the former Israel State Archivist, and was previously the archives director at Yad Vashem. His Twitter feed is @yaacovlozowick.