Whoppers

A former student remembers a seminar with Chaim Grade—and how it changed his life

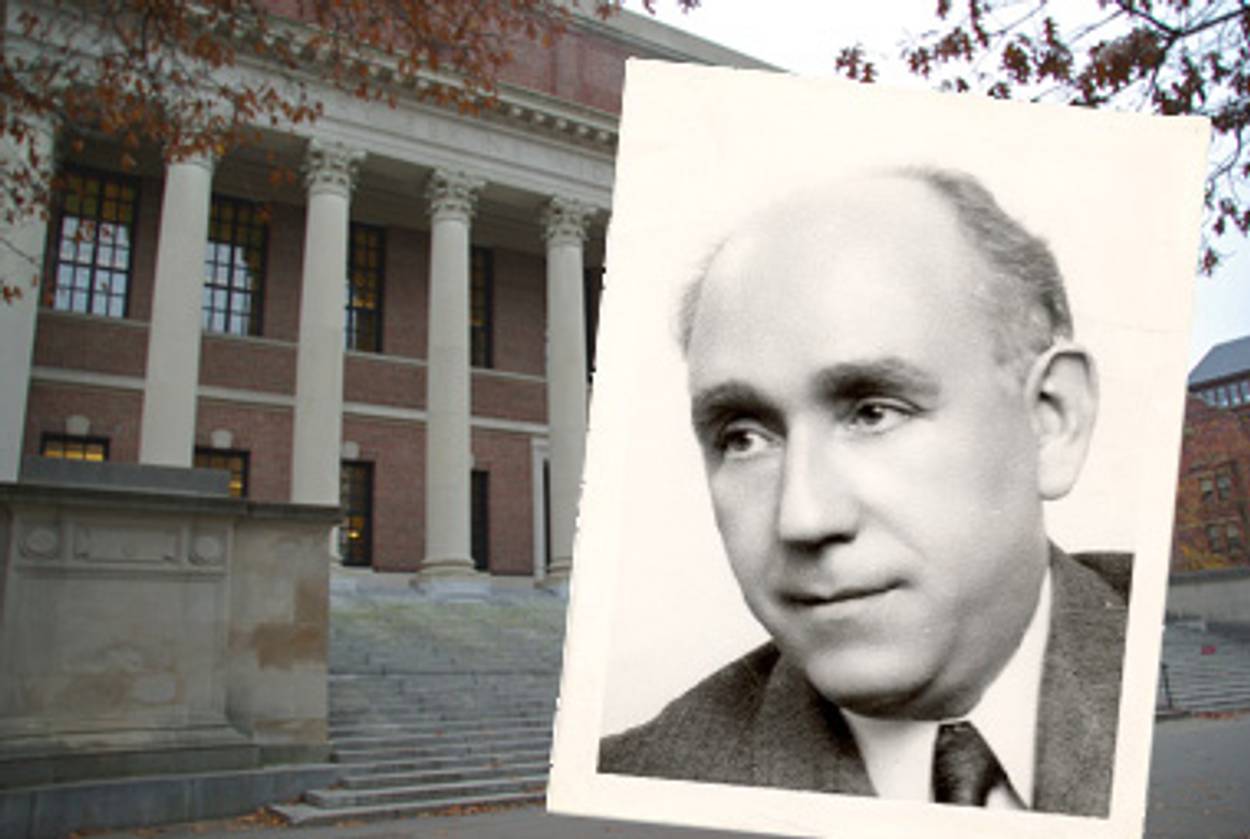

I fell in love with Chaim Grade before we exchanged a single word.

From the moment he stormed into our graduate seminar in the storied “Room G” of Harvard’s Widener Library to deliver the first of his series of talks on East European Jewish Culture in 1977—the first classes ever held in Yiddish at Harvard—I was enthralled by the power of his personality, mesmerized by his brilliantly poetic rendition of otherwise dry academic subjects, and awed by his mastery of, and love for, his subject.

Following the session, which took place in the former office and personal library of Harry Wolfson, we were asked by our teacher, the late Isadore Twersky, to take Mr. Grade to lunch. Instead, after delivering his exhausting tour de force about the contrasts between the worlds of Hasidim and Misnagdim, Grade sprang from his chair and demanded of us—a small group of Yiddishly literate graduate students—to show him where Harry Wolfson’s Spinoza books were shelved. (Among his many major works, Wolfson was the author of the magisterial two-volume The Philosophy of Spinoza.)

“I want to be sure that Wolfson didn’t own any Spinoza books that I don’t have,” he said. “Lunch can wait.”

At the time, I was a young, earnestly Orthodox Jew, and I naively asked Grade why he was so interested in Spinoza. He positioned his nose inches from mine, laughed, and then shouted: “He who has not read the Tractatus, knows nothing about modern thought.” That evening, I discreetly picked up a copy of Spinoza’s notorious critique of religion, took it home, and over the next three weeks studied it—though only, I should add, while on the toilet. After all, such heretical works—known in the yeshiva world as trayf-posuls (both unkosher and forbidden to use)—are allowed no place other than the one in which a kosher book is forbidden.

Yes, I was that frum. Or so I had believed.

As the only member of our little group of graduate students who owned a car—the happiest perk of a part-time rabbinical position in Boston—I became Grade’s designated driver, picking him up at Logan Airport and then shuttling him back and forth to campus. And so we got to know each other over the next few months—during which Grade developed notions about my soul that were entirely different from my own.

One night, Grade arrived very late due to a flight delay, and this time the food could not wait: He insisted that we stop at a Burger King, the first restaurant we passed after exiting the airport tunnel. When he offered to buy me a Whopper, I protested that I couldn’t eat it.

“Farvos nisht?” Grade impatiently demanded. (“Why not?)

“Vayl ikh bin frum; nit nor frum, nor a Rov!” I said. (“Because I am not only religious; I am a rabbi!”)

“A Rov?” he laughed, “Du bist der Royter Rov!” (“You are the Red Rabbi.”) There was a tinge of red in my beard back then, but what Grade really meant was that there was more than a touch of red subversiveness in my soul, of which I was not yet aware.

He never again called me by any other name. And over the years, I slowly, often painfully, grew into the fullness of that very loaded nickname, bestowed on me by this prophetic poet, a former Talmudic prodigy destined himself to be a great rabbi, but whochose instead the life of a secular poet; who had survived the Holocaust only thanks to the Godless Soviet Red Army.

In Yiddishist circles, Grade was famous for (though not particularly loved on account of) his gruff and stormy personality and his explosive temper. He suffered neither fools nor mediocre writers lightly. But these harsh traits masked a passionate humanism. He always displayed an earnest, probing curiosity about each of the students who attended his seminar, one that far transcended conventional academic interests. Like all great writers, he peppered us with personal, often “inappropriate,” questions, half of whose answers he angrily rejected as self-delusion. He berated us mercilessly for our naiveté, for our lack of introspection, and especially for our emotional immaturity. But the loving, parental concern lying behind those harsh admonitions was evident—and moving.

In fact, more than any of my other teachers, Grade took a deep interest in my studies. When I told him I was planning to write my doctoral dissertation about the history of halakhic literature in early modern Germany, he quickly dismissed the theme as both boring and ill-suited to my personality. Instead, he called my attention to an obscure Lithuanian maggid named Pinchas of Polotsk, a disciple of the Gaon of Vilna. The next day, I skeptically searched the Widener card catalog for titles by him and came across a little masterpiece, Keter Torah, a powerful polemic against both Hasidism and the Enlightenment.

A day later, I informed Twersky that I had decided to write my dissertation about the Misnagdim, based on Pinchas’s work. Twersky, unfamiliar with this author, was reluctant, but when I told him the idea came from Grade, he approved the proposal immediately. Years later, long after Grade’s death, I published my first book, about the Misnagdim. And today, several bookshelves in my home groan from the weight of my Spinoziana, in English, Hebrew, and Yiddish. I have often wondered if Grade had any books missing from those shelves.

The greatest moment in Grade’s brief career at Harvard was a public lecture he delivered in Yiddish about the Hebrew national poet, Hayyim Nachman Bialik, before hundreds, many of them survivors. The very first work of Grade’s I had studied—just a few years before he appeared at Harvard—was his masterful epic ballad Mussernikes, depicting the austere lives of the students in Lithuania’s most-demanding yeshivas. While listening to Grade’s lecture, Bialik’s poem, “ha-Masmid,” about the last lonely Yeshiva bokher in Lithuania, rang in my ears. As he went on, I began to understand how deeply Grade identified with Bialik; that, in fact, Grade was the Yiddish Bialik, encompassing in his stormy soul all of the pathos and painful contradictions that defined Zionism’s greatest poet’s work, to say nothing of his prophetic voice.

Grade never expected to be lecturing to young students at Harvard, and the surprising experience enlivened him, even as it did us. For too many decades his only audience had been a dying generation of native Yiddish readers, mostly survivors. He told me, after our last seminar, that the visits to Harvard gave him a renewed energy to write, as had a life-changing trip to Israel in the 1960’s. Before boarding his last flight out of Logan Airport, Grade asked me to read his poem “Oyf Mayn Veg Tsu Dir” (“On My Way to You”)—the title work of his Yiddish-Hebrew bilingual collection (Tel Aviv, 1969) inspired by that visit to the Holy Land. It ends,

My lonely destiny, I once sadly thought determined

But our surprising encounter too was divinely destined.

God had finally dragged me from my old, alien bed

And forged from our fresh encounter a new being

It is no easy matter to love equally the heretic Spinoza and the religiously intolerant Maggid of Polotsk; to embrace the secular world and enjoy a good Whopper, all the while dedicating one’s life to erecting a magnificent literary monument to the lost world of Lithuanian Jewish piety, which is Grade’s greatest bequest to Yiddish literature. The unbearable burden inherent in maintaining an abiding love for the Jewish religious past and a lifelong dedication to preserving its memory, embedded in the heart of a true apikores who still believes God is acting in his life, defined the pain that Grade shared fully with Bialik, and one he transmitted, at least in some small part, to me. It is a cross I humbly and so gratefully have carried since Grade’s passing, almost three decades ago. Had God not dragged Grade from that tired bed and allowed me to share a small part of his burden, I would never have discovered who I really am.

Allan Nadler, a professor of religious studies and director of the program in Jewish Studies at Drew University, is currently a visiting professor of Jewish Studies at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

Allan Nadler, a professor of religious studies and director of the program in Jewish Studies at Drew University, is currently a visiting professor of Jewish Studies at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.