Why Pop Art Is Jewish

A Roy Lichtenstein show at the Art Institute of Chicago reveals the movement’s affront to WASPy decorum

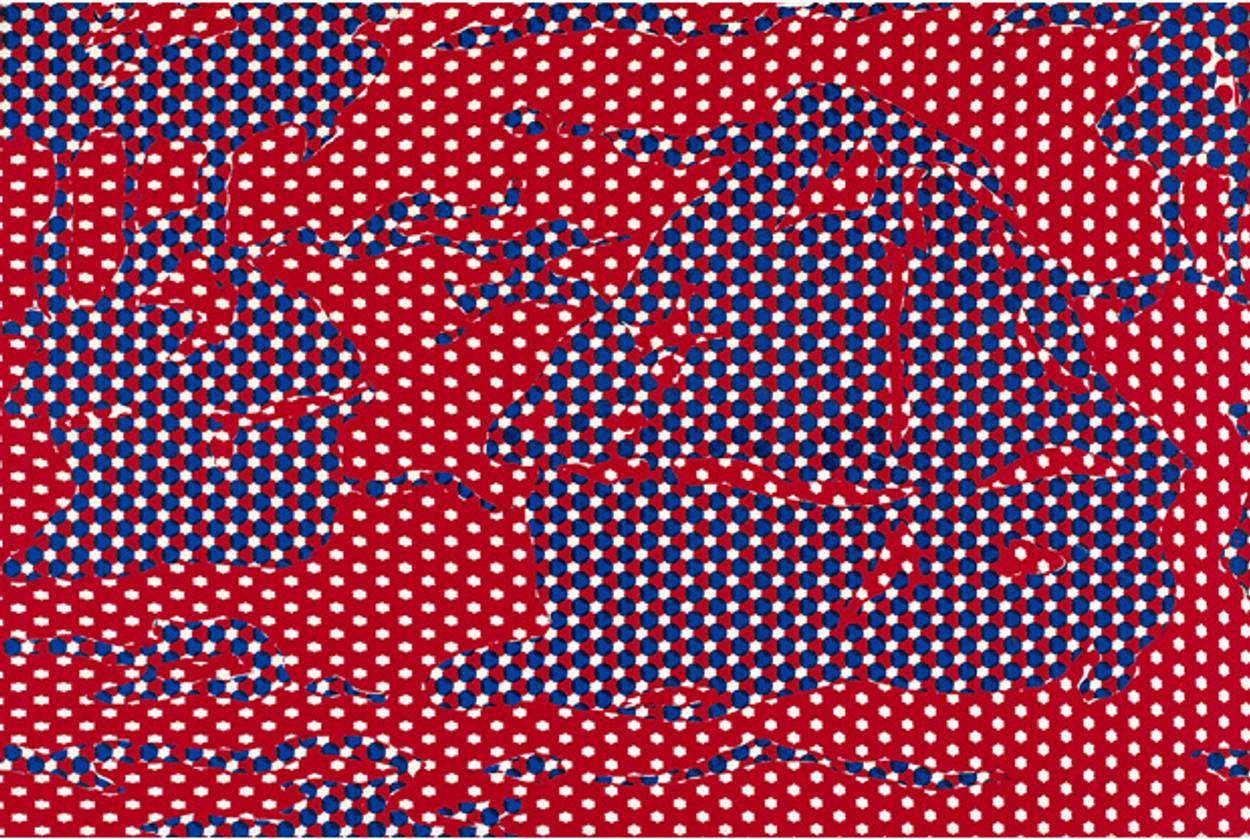

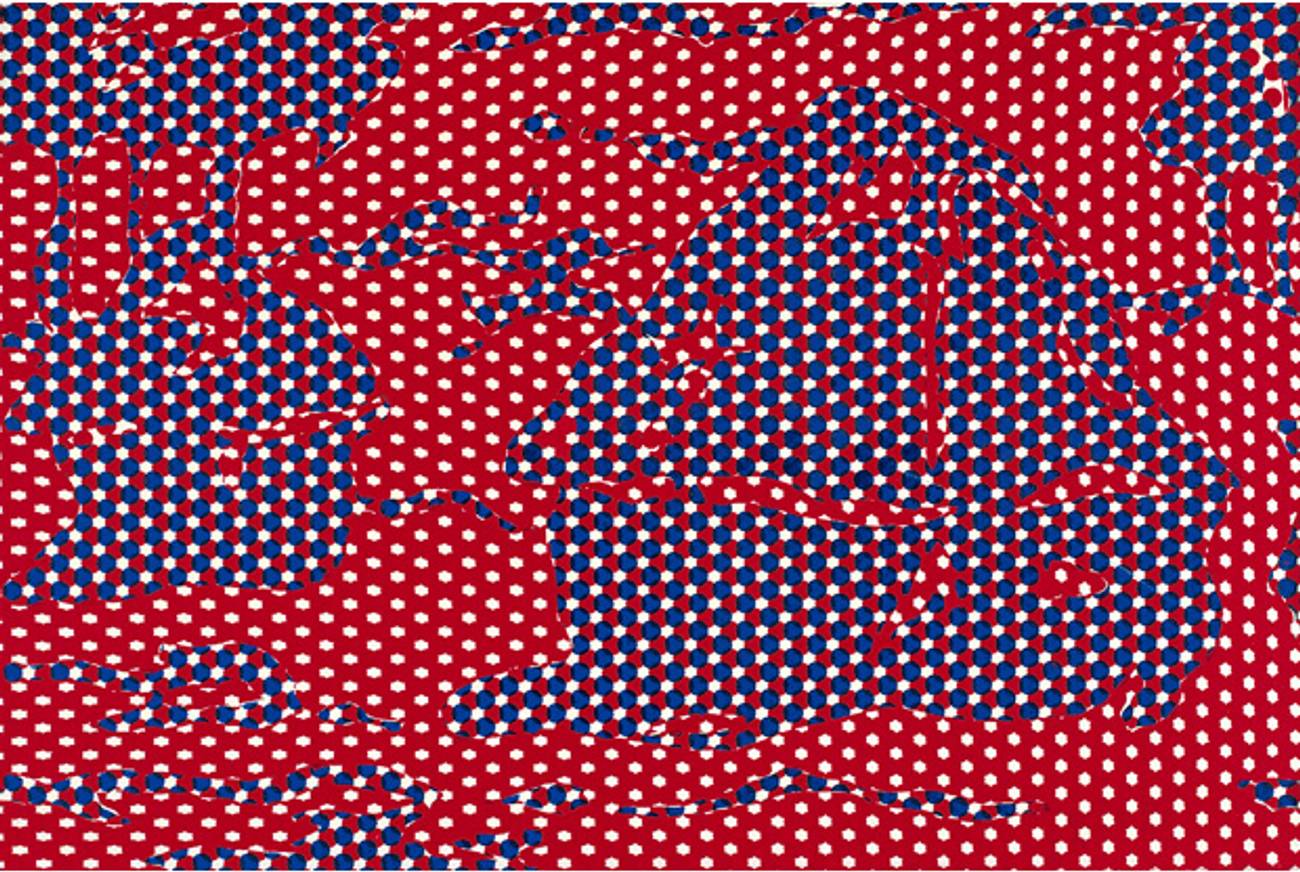

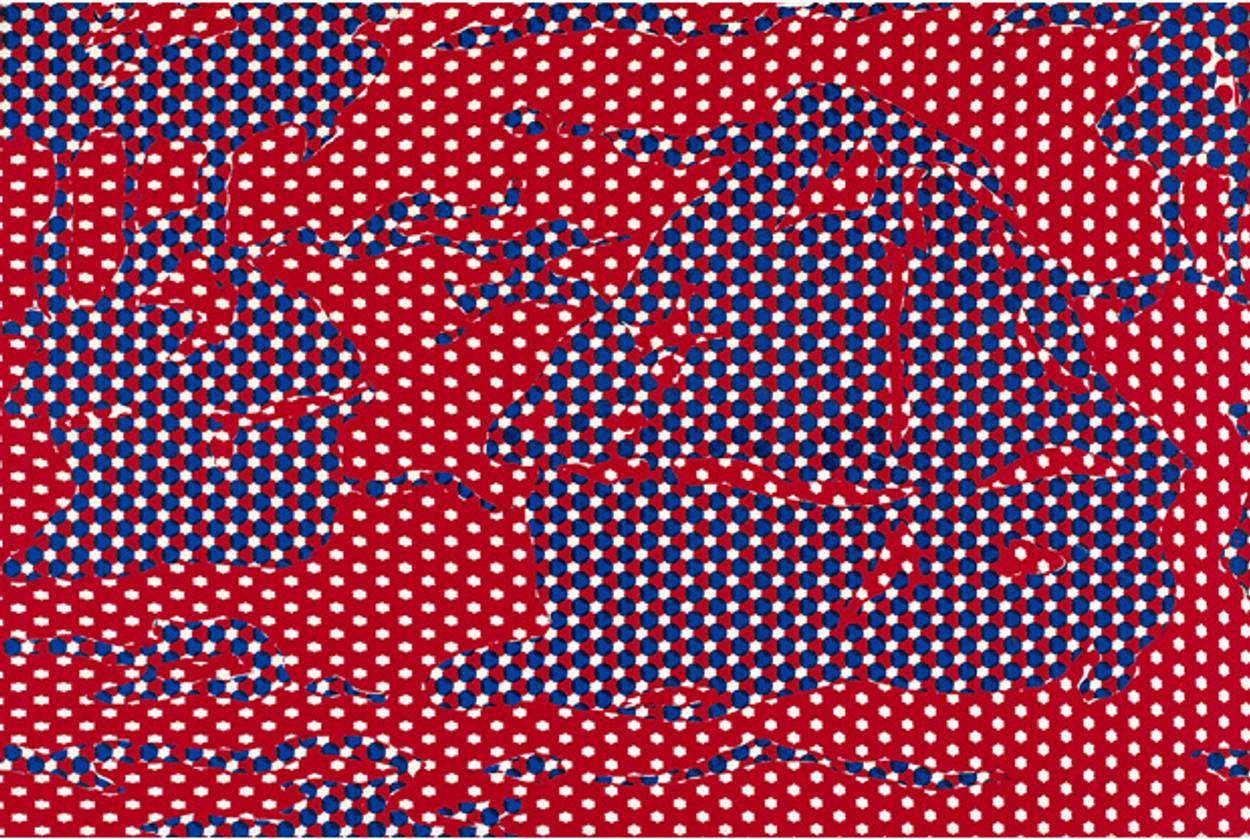

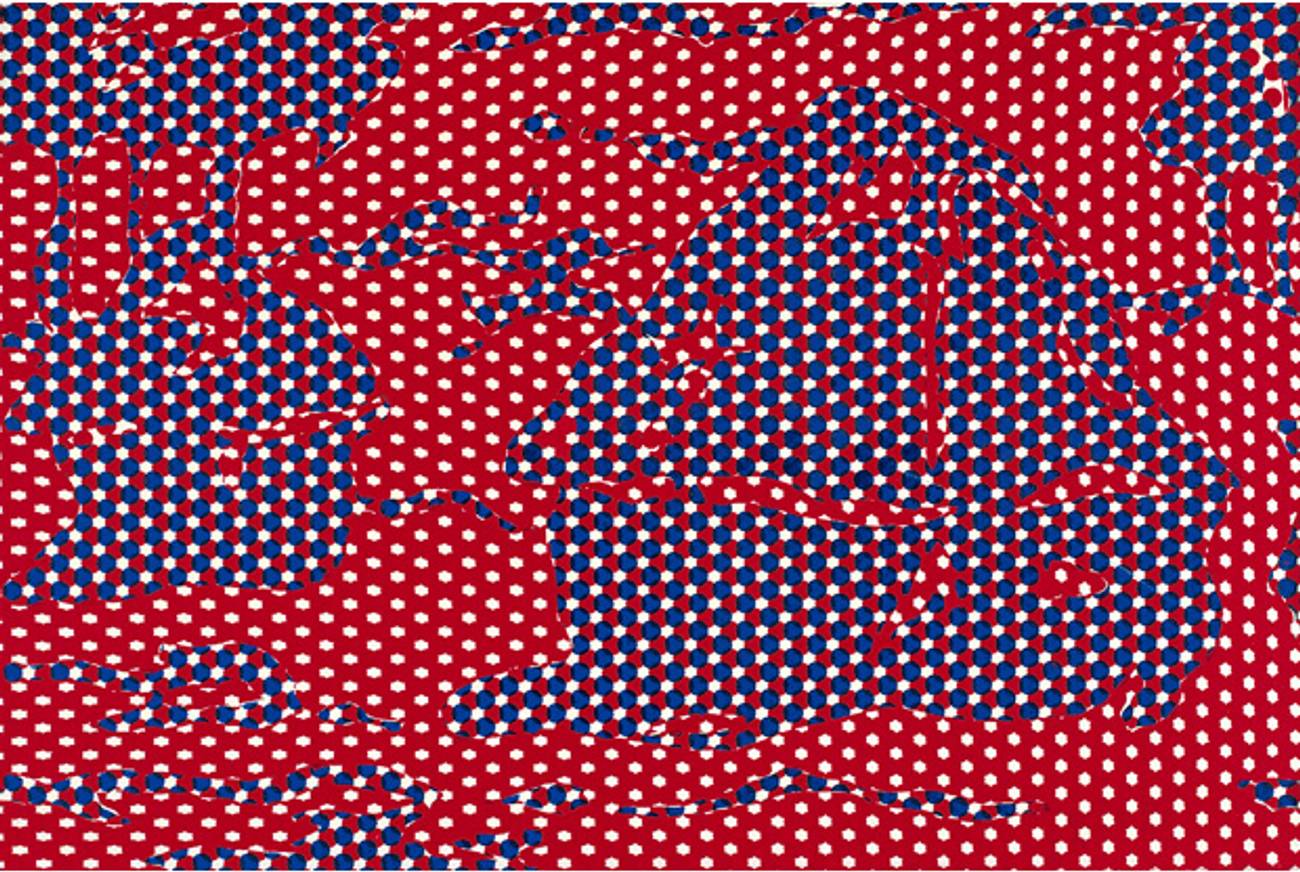

Roy Lichtenstein, whose painting “Sleeping Girl” sold last week at Sotheby’s for $44.8 million, a record for his work, is one of those Jewish artists whose art is rarely if ever connected to their Jewishness. This is not only because his subject matter is not Jewish—a literary equivalent from the same generation is Norman Mailer, with whom Lichtenstein shared the bracket of his life 1923-2007—but also because of the objective coolness of his compositions. In Paris, when Chagall and Soutine were both living and working there in the early years of the 20th century it was, strangely, and perhaps anti-Semitically, Soutine who was considered by critics to be the exemplary Jewish painter because, while he never took on Jewish subject matter, his expressionism was read as a type of over-emoting common to Jews. Reactions to Rothko sometimes work along these lines. Lichtenstein’s Ben-Day dots, comic-strip figures, and industrialized canvases resist even a hint of residual emotional expression and with one small exception, a parodic Chagallesque fiddler inserted into a large mural that he donated to the Tel Aviv Museum in 1989, he certainly wasn’t interested in Jewish themes. One faux Chagall doesn’t make a summer, and Lichtenstein’s oeuvre entirely escapes, it would seem, any kind of categorization as that of a Jewish painter.

Plus, Pop Art isn’t Jewish, or hasn’t been seen as such. Its concerns are entirely elsewhere and include the economics of printing, the industrialization of images, cultural vulgarization, and the way that, as Somerset Maugham once asserted, “Man in extremity sounds like a cheap novel.” But it was Jewish for me in 1968 when I first saw Lichtenstein’s work in what was generally regarded as a sensational, subversive show at London’s Tate Gallery. I was 17 and I lined up for a long time on a cold January day for the pleasure of standing in front of “WHAAM !”—one of the paintings currently on exhibit in the wonderfully comprehensive Lichtenstein retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago opening today—and all the other oversized, glorious (to a 17-year-old) comic-strip adaptations.

Why Jewish? Because I assimilated Lichtenstein’s paintings as an affront to convention and to what I perceived as the stultifying and exclusive tastefulness and establishment decorum of the WASP world. An American Jew rocking the Tate Gallery looked like good news to me. Saul Bellow, reflecting on the cramped and claustrophobic atmosphere of his first two novels Dangling Man (1944) and The Victim (1948), explained that they emerged from “the incredible effrontery of announcing [him]self to the world ( … the WASP world) as a writer and as an artist” a feeling that only fell away when he began to write his breakthrough third novel, The Adventures of Augie March. Perhaps I was being as silly as the French critics who responded to Soutine’s expressionism as Jewish, mistaking pictorial exuberance for an ethnic endorsement. Only a year after the Lichtenstein show, Portnoy’s Complaint came along, and nothing was hidden after that.

***

The current retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago, the largest since Lichtenstein’s death, unfolds in room after room. The progression is chronological with occasional breaks in the continuity for sculpture and significant groupings, like Lichtenstein’s ersatz reworking of Mondrian, Matisse, Monet, and others that also features his sublimely antic nascent pop version of Emanuel Leutze’s “Washington Crossing the Delaware.” The cumulative effect is in the end less powerful than the rooms that house “WHAAM!” and the other breakthrough paintings from 1962 to 1965 that include the clairvoyant “WHY, BRAD DARLING, THIS PAINTING IS A MASTERPIECE! MY, SOON YOU’LL HAVE ALL OF NEW YORK CLAMORING FOR YOUR WORK!” These war and romance paintings still carry a terrific wallop, the good old shock of the new. Yet elsewhere, Lichtenstein’s endless quotation of others and of himself—whether it’s landscapes in the Chinese style or paintings of his own studio featuring his early works on the walls—sometimes makes it seem as if we are reading an extraordinarily long footnote. The last room is devoted to a series of nudes that Lichtenstein produced in his seventies: The AARP years frequently return male artists to the naked figure. Here we have comic-strip girls with a beach ball, others who are by turns sultry, anxious, pensive: all shaded in Ben-Day dots. Lichtenstein’s late nudes are not priapic like Picasso’s but, true to form, cerebral, distanced by the inevitable quotation marks and his foregrounded concerns with composition.

During the Lichtenstein show’s brief stay at the Tate in 1968—little more than a month—the People’s Army of Vietnam launched its Tet offensive, the Americans responded, and “WHAAM!”, which Lichtenstein had adapted from an image in the 1962 D.C. comic All American Men of War, suddenly looked like the most prescient and economical depiction of the destructive power and cultural wackiness of the United States in Vietnam. After all, this was a war in which some men went into battle wearing Batman outfits. If the big idea behind the great American comic strip and its animated cousin was to make death unreal (Daffy Duck can withstand any number of shotgun blasts) and in that way to endorse any kind of trespass because it has no consequences (bomb Hanoi!), then Vietnam was the place to test that idea in action. The things they carried were to ward off darkness, the invisible enemy, and death, but if you could convince yourself that you had superpowers and the constitution of a two-dimensional illustration whose bullet-holes in the abdomen miraculously sealed up in the next frame, so much the better. Repetitive, sterilizing TV news, long-distance bombing, everything conspired to make sure that nothing of any relevance got through. By painting war bigger, bolder, brighter, and more deranged in its distance than even its architects wanted it to be, Lichtenstein appeared to expose and explode the lie.

Nothing, of course, could have been further from his intention; he wasn’t overtly political, he was an ironist. The passing years made this clear, and the Chicago show reifies this perspective. “It’s art about art about art,” Marc Sheps, the director of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, commented when the mural there, a diptych on permanent display that is half abstract and half figurative, was unveiled. He was right, not only about the mural but all Lichtenstein’s work. Lichtenstein was interested in the way in which ways of seeing had been altered by what Barbara Rose, in the year before the Tate show, called “discredited mass culture sources … advertisements, billboards, comic books, movies and TV.” He was far less interested in his subject matter than his audience, had no message to get across except to reflect the industrialized, super-material aspect of American life, in which, through his acknowledged “vulgar” renderings of work by the great masters (he did to Picasso what Picasso had done to Velázquez) he also participated.

In all likelihood there has rarely been an artist for whom the discrepancy between his own concerns and those of his audience has been greater. Lichtenstein, who worked for many years as an abstractionist and continued to think of his subject matter as abstract even after he had turned to the comic strip for inspiration, became, despite himself, the poster boy for, well, posters. Warhol, that enigma wrapped inside a pastry, appeared to share the Pop Art joke with his audience: America was spiritually vacant and ludicrous, when he silk-screened 200 one-dollar bills we all got it. Five years ago that first 1962 silk-screen painting went for $43.8 million on the auction block at Sotheby’s, which is as the world turns. Warhol enacted his art, reproduced himself, and showed up everywhere. Reviewing Warhol’s diaries in the New York Times Book Review in June 1989, Martin Amis listed some representative events: “the opening of an escalator at Bergdorf Goodman … an ice cream-shop unveiling in Palm Beach, a Barbie Doll bash, someplace to judge a Madonna-lookalike playoff and someplace else to judge a naked-breast contest.” Amis adds, “It strains you to imagine the kind of invitation Andy might turn down. To the refurbishment of a fire exit at the Chase Manhattan Bank? To early heats of a wet-leotard competition in Long Island City?” By contrast, Lichtenstein was reclusive and rarely broke his inexorable work routine—in the studio at 10 a.m., lunch at 1 p.m., return to studio until 6. In a 1987 interview in the New York Times, when Deborah Solomon asked him what holidays he celebrated, he had a hard time coming up with an answer until he remembered he had been at a friend’s for Thanksgiving. No wonder he painted an anxious blonde with a white-gloved hand held to her cheek whose thought-bubble reads, “M-Maybe he became ill and couldn’t leave the studio!” You can see her in Chicago.

Norman Mailer once affirmed that his reading of the Talmud influenced everything he had written. You’d have to do some digging, of course, to see how. The chronology provided on the website of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation does not even bother to mention that Lichtenstein’s Brooklyn-born real-estate broker father Milton and his mother Beatrice, born in New Orleans, were both Jewish, although the catalog for the Chicago show does parse his German-Jewish ancestry. Lichtenstein visited Israel for the first time in 1987 when he was 64 and discussed the possibility of the large mural that presently graces the lobby of the Tel Aviv Museum. Lichtenstein’s gift—he said at the time that he “wanted to give something to Israel”—was not without controversy, some vocal groups felt the wall should have been made available to a local artist. Lichtenstein, who the previous year had signed a telegram urging the Israeli government to negotiate with the Palestinians, remained above the fray and took a different tack, observing that the mural was meant for “anyone in the area.”

In his extraordinary and brilliant meditation on Freud’s relationship to his own Jewishness in Freud’s Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi speculates that Freud’s attachment to and knowledge of things Jewish was far deeper than the great man liked to let on. Yerushalmi offers two wonderfully dubious yet curiously persuasive arguments in support of his thesis: First, Freud had a dog named Jofi, which had to be a Germanization of Yoffi; and second, Freud’s father gave him a Bible with a lengthy Hebrew inscription, and who would do that if the recipient couldn’t understand the language? In Roy Lichtenstein in His Studio, a portfolio of photographs by Laurie Lambrecht of the artist at work, only one image appears twice. It shows Lichtenstein seated in a chair at work on a canvas. He looks quite at home in this particular spot. Above the canvas one can clearly see the bottom of a poster for one of his shows: The words “art of the sixties” appear in both Hebrew and English. Perhaps Pop Art is Jewish after all?

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jonathan Wilson, the director of the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University, is the author of, among other books, the Nextbook Press biography of Marc Chagall.

Jonathan Wilson is the author of eight books including the novel A Palestine Affair and a biography, Marc Chagall. He recently completed a novel, Hotel Cinema, about the unsolved murder of Chaim Arlosoroff.