Writing Your Way Out

In conversation with Shulem Deen’s new ‘All Who Go Do Not Return,’ a book that doesn’t give readers everything they want

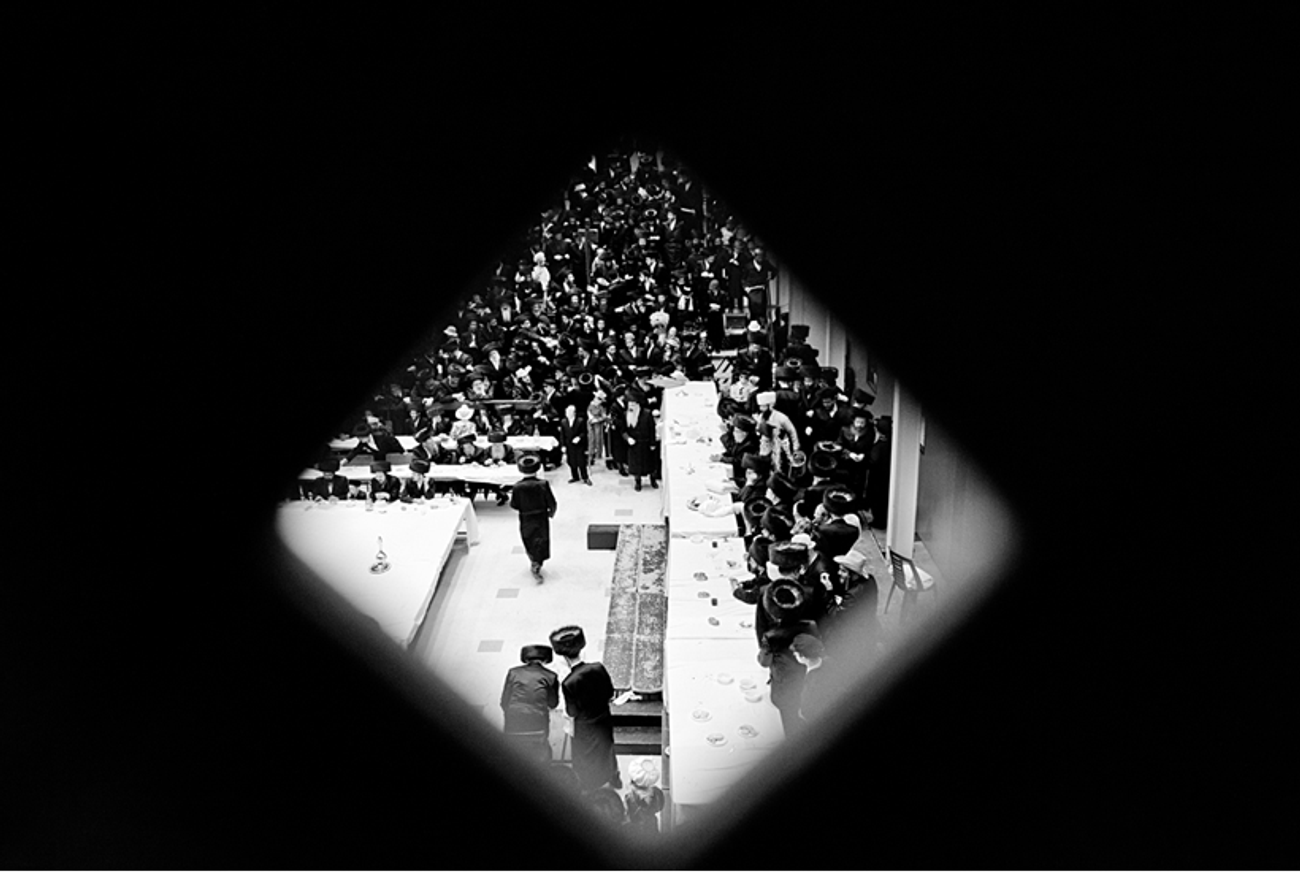

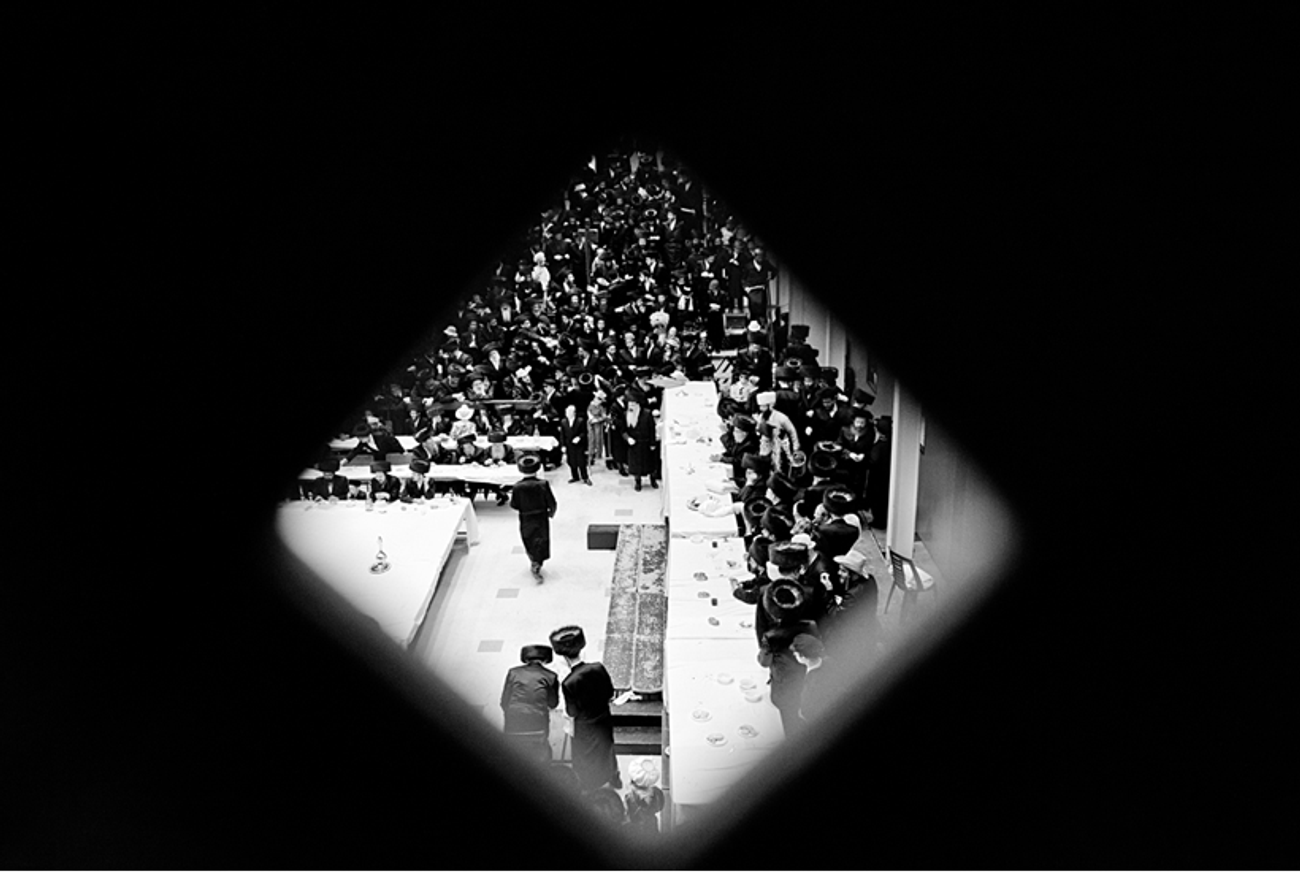

New Square, populated primarily by Skver Hasidim, is in Rockland County, New York. The town was founded in the mid-1950s by Rebbe Yakov Yosef Twerski and modeled after the Ukranian shtetl Skvyra–“New Square” was a typist’s error. Like other Hasidic communities in New York, the Skverer village was created by Holocaust survivors’ determination to preserve a Jewish way of life–a need to not perish–perhaps at all cost. In the case of New Square, the cost is near-fanaticism.

Where the practices of Hasidic sects vary significantly, from the Satmars in Williamsburg to the Lubavitchers in Crown Heights to Vizhnitz in Monsey, and even between households, the Skverers in New Square are known for being particularly pious and strict. Their abstinence from the modern world is as total as can likely be achieved by a group living on the border of the greatest metropolis in the country. Television, Internet, secular books, radio, and movies are typically forbidden. And so too are certain questions. Like, why. For Shulem Deen, whose memoir All Who Go Do Not Return, out this month from Graywolf Press, asking why—why do we live this way, why do we believe what we believe—led to his being declared a heretic by New Square’s rabbinical court, the fallout including a divorce from his wife of almost 15 years, the loss of visitation rights to his five children, and eventually, his disavowal of Hasidic life.

The drive from New York City to New Square takes about an hour, according to Google maps. Following this primary-colored digital path onscreen is the closest I will likely come to visiting the village, as a religiously unaffiliated young woman whose Judaism runs no deeper than nostalgia for her grandmother’s matzoh brei. But I am fascinated by the place, and I can appreciate the need to define oneself as separate from one’s upbringing. I understand that even if I did visit New Square I would have no greater access to Hasidic life than my occasional walk through Williamsburg, where I can see but can’t penetrate its appeal, or its secrets. Deen’s memoir, however, does grant me that access. It is the book’s ticket to mass appeal as well as the seat of his disquiet in its writing.

Deen has written about his experiences over the years, as a blogger, as a contributor to Tablet, and as founder and editor of the website Unpious. Though he writes because he has a story to tell, Deen’s work, especially in his memoir, is clearly crafted to benefit others dealing with a wavering faith. He’s involved with Footsteps, an organization that supports those leaving ultra-Orthodox life, and he dedicates a couple of his final pages to a reading list of books on religious faith, a disclaimer that his book isn’t an “argument against Orthodoxy,” and a note that his narrative had to bluntly externalize an “internal process of inquiry and examination.”

It is a fascinating trinity of problems: describing a secret world while attempting to protect it, uncovering personal secrets while guarding those of others, and exposing the fault in a discipline while exposing the need for discipline. How strange is Deen’s story in comparison to that of the imagined ordinary reader? For me, not much. My own story happens to involve a spiritual morality, the isolation of the “unschooler,” and a guru’s community in California.

About an hour and a half from Sacramento, the community was made up of people from various backgrounds drawn to the spiritual teachings of an enlightened woman who professed to help her “devotees” open their hearts to God. Heart opening was experientially validated and has no easy description, though the general idea was that the guru was a bridge to the divine. We began attending in 1999, on Saturdays and for weeklong retreats, and took part in the planning of a fully realized live-in community, dubbed the Mother Center. Though we saw the completion of the Mother Center, and lived with other devotees, we did not in the end move to the property. After a series of events, including the dismissal of many people around us, we found we were no longer welcome even as attendees.

For a long time I have avoided answering the question, “How was junior high and high school, for you?” because it was enough of a conversation stopper to admit that, save for about a year and a half, I’d not gone. That during those years when I’d “disappeared” from friend circles, I was often with my mom in the hills outside of our suburb, chanting into the night as around us people shook and wept, waiting for our guru to make an appearance, give us her blessing, and deliver her breathy sermons.

My own compulsion to write about these things now gives me purpose, a ritual outlet, and a way to name why I am who I am. It also presents me with a problem inherent to the genre: My story is the story of many people. Whose secrets will I tell, whose lives will I carelessly summarize, whose love will I lose; why am I the one compelled to write? If I felt naively led to believe in things I later decided were wrong, or harmful, then by telling my story am I similarly exposing others to an unkind world? Left untouched, undiscovered, the world I came from might remain to those who need it to be that way: holy.

***

All Who Go Do Not Return opens with Deen’s dismissal from New Square and then begins again with the story of his adulthood. Born to liberal parents who are baalei teshuvah, those who adopt (“return” to) Orthodox life, in Brooklyn, Deen chooses a Skverer yeshiva because he hears that the entrance exams aren’t exceptionally rigorous. What he lacks in studiousness he gains in devotion, and he decides to become a scholar. Married just before he turns 18 years old to a woman he refers to as Gitty, Deen starts a family.

Up to this point, Deen’s life has been one of focused religious learning. As a husband he is confronted with myriad banal realities of which he is almost completely ignorant, like being with a woman, having sex, raising children, earning money. After marrying, Deen applies for a kollel stipend, available to students who want to learn full-time. In the years following he watches the amount allotted him grow smaller with the birth of each child.

“At first, raising and providing for a family had seemed simple enough,” writes Deen. “Everyone did it, more or less, and so I imagined there must be a formula, the specifics of which I would learn in due time. The important thing was to start the process. I assumed that the ‘system,’ the birth-to-death cocoon of institutions and support networks available for every Hasidic person, would take care of the rest.” But $430 a month proves to be less a cocoon than a thin blanket. Behind on rent, owing the grocer, Deen begins looking for ways to make money.

By this time, the feeling that he is not a man, in the sense of one who knows how to care for himself, has begun picking away at Deen’s core, a delicate fiber: His identity, when examined, has become for him too blatantly constructed by disinterested human hands, not God’s and not his own. “My passion for study, piety, and prayer was mostly forgotten. Now I wondered only how I was going to support my family. After rotating through a half-dozen jobs in as many months, I felt increasingly as if I were not a grown-up but a child.”

Deen’s story of necessity and resourcefulness unfolds alongside the arc of his disenchantment. What initially drew him to the Skvers was their seemingly pure commitment to faith–their modest lifestyle aligned with scriptural anecdotes; they meant the words they prayed. It was something Deen hadn’t experienced before a trip to New Square: “For the very first time, it occurred to me that being a Hasid allowed for more than the daily grind of studying Talmud and adhering to the minutiae of our religious laws. … Here was the ecstasy and the joy. Here was all that I had been told that we Hasidim once had and lost.” But despite this attraction to absolutism, the seeds of Deen’s problematic inquisitiveness, he writes, had been germinating from a young age. A handful of events show Deen’s indulgence in curiosity–finding and reading a neighbor girl’s Judy Blume book as a boy, and later, a friendship with a man who had taken up kiruv work (teaching Jews the merits of living by Jewish law in the hope that they will adopt it), with whom he watches movies and debates faith based in reason.

Other events—like when teenagers drive a car through the village one night yelling anti-Semitic epithets and Deen, alone, rallies the men of New Square into a charge, hurling stones and stakes at the car—demonstrate a crescendo of Deen’s fervor; how when brought to a boil it cracks, inverts, and becomes the hollow shame of one who has been moved to action by something he can’t explain. “What made us so quick to rally a mob and pursue a group of young people for what really were, in this incident, no more than harmless insults? … And if we had caught up with the car, what would we have done to them?”

It is the story, too, of a radio that Deen uses as a physical turning point, when he crosses an empirical boundary between obedient and rogue. A stereo he buys to play cassettes for his children comes with a built-in AM/FM dial that should, writes Deen, be glued immobile–common for an Orthodox household. One night after his family has gone to sleep, Deen attaches headphones to the radio and switches the dial, never glued, to AM. What he hears is a mess of sound, each transmission as interesting as the next commercial or traffic update. Once Deen succumbs to the temptation of exploring all that there is that he doesn’t know, he can’t stop: “All who go to her do not return. Heretics, the rabbis said, can never repent.”

Deen’s curiosity is insatiable, his questioning is unrelenting. He can’t hide it from his wife or his community. More troubling to him, he doesn’t want to hide. He starts a blog about his life, and, as it gains a following, word of the “Hasidic Rebel,” as the blog is called, spreads. Though he blogs anonymously, Deen is suspected of being the author. He has already acquired a reputation as someone with too many questions. A young man who has heard of Deen comes to him for advice on leaving New Square.

After Deen is called to the rabbinical court and labeled a heretic, his life quickly falls apart. Though he moves with Gitty to a more liberal community in Monsey, he can no longer maintain the practice of Hasidism. Deen and Gitty are divorced, he finds his own apartment, and he begins taking college courses. Eventually he loses his children, first because his visitation rights are reduced and then because of their understanding of how his difference affects their place in the community. It is heartbreaking, and Deen ends, carefully avoiding a simplistic polarization of life-as-pious and not, facing the near unbearable loneliness of infinite choice in secular New York City.

***

Seen as an artifact of the contemporary publishing business, Deen’s memoir belongs to the OTD, or “off-the-derech,” off-the-path, genre; the ex-frum, or ex-Orthodox. The ex-frum memoir usually details the events surrounding a crisis of faith. The author’s loss of family or community or his or her subsequent negotiation of the secular drives the narrative, while as in the case of Deen, descriptions of the life they’ve come from help to unify the chronology of their disenchantment, impossible to peg to any one event or thought. As Tova Ross wrote in Tablet last year, the ex-frum genre includes Shalom Auslander’s Foreskin’s Lament, Deborah Feldman’s Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots, and Exodus; and Leah Vincent’s Cut Me Loose: Sin and Salvation After My Ultra-Orthodox Girlhood.

“These ‘micro-trends’ tend to happen because one book is published, which gives others the courage to tell their story,” said Emily Murdock Baker, editor at Penguin Books who recently bought paperback rights to Vincent’s Cut Me Loose. “On a broad level,” Murdock Baker said, “this kind of book gives people access to cloistered communities, like the Orthodox or the Amish. Leah’s story is very particular to that experience of leaving an Orthodox community, but there’s a lot that people of many backgrounds can relate to—rejecting your parents’ ideals, coming of age; how it is really hard to figure out your place in the world. Memoirs are a consistently popular genre because readers want to peel back the curtain on other people’s lives. In a memoir someone is offering up their secrets to you. That’s endlessly appealing.”

Vincent’s book describes her path from studious, smart yeshivish girl (“the ‘Yeshivish,’ ” explains Vincent, are “committed to the centrality of the yeshivas—study halls where men ponder ancient legal texts”; the term also refers to ultra-Orthodox who are not Hasidic) in Pittsburgh to errant teenager and sinful adult. Her break from family occurs early in the book after she is too vocal about her opinions and then is found out to have asked a boy to hold her hand. Similar to Deen’s, Vincent’s book deals less in the secrets of the ultra-Orthodox than in the attempt to define an identity and gain a sense of self. Though OTD books have been criticized for being poorly written, both Deen and Vincent’s are written for wide appeal and without the assumption that the story, which is intriguing, supersedes the need for literary storytelling.

Like Deen, Vincent highlights the complexity in deciding to leave Orthodox life: “I did not know anyone my own age who had gone frei—literally, free. But I knew what happened to those who did. Sinning might seem like all bright lights and loud music, but being free had all the fun of a crazy carnival Tilt-A-Whirl—you’d be hurling in the gutter in no time. I had heard stories about those who left our Yeshivish community. They wound up drug addicts, prostitutes, or dead.”

Vincent winds up in New York City, where she enrolls in college courses, sleeps with men in a series of one night stands and quick, brutal relationships; contracts a sexually transmitted disease that could render her infertile–the ultimate denial of her identity as a yeshivish woman–and develops a habit of cutting. She does eventually find a sort of peace: Her story concludes with her acceptance to Harvard grad school and a nice relationship.

Hers is a coming-of-age story sharpened by a naiveté that serves as incidental narrative device, the defamiliarization of “everyday America.” Set in this “unfamiliar America” Vincent’s actions, which to her are logical, are to a reader, perilous. We see how her sheltered upbringing renders her helpless to create a life of her own design. She describes her journey from an emotional remove that gives us the sense that she is again aware of the invasion of her person–her secrets, the intimate details of her disgrace. Her vulnerability is on display, but offering herself up like this, as author, is an empowering prostration. The relationship between writer and audience is on her terms, the memoirist’s, and it is clear she understands exactly how she benefits from the exchange.

***

The OTD memoir may be particular to the ex-Orthodox author, but telling the story of becoming unreligious is not new. In fact it fits neatly into the larger tradition of the memoir itself, whose “religious DNA,” as Daniel Mendelsohn wrote in The New Yorker, has been successfully regenerating since St. Augustine began writing his Confessions in 397 C.E., in which he transforms from sinner to saved. The trope has shifted in various environments: inverted from “sinner-to-saved” by an American religious predilection to then become the confession of “I am shameful” as practice, and again with politics to include records of “systemic injustice” overcome––slavery, persecution, genocide. “As the ‘I’ became ‘we,’ the personal journey that had begun in the fourth century was transformed, by the end of the eighteenth, into a highly political one,” Mendelsohn wrote. “The conversation between one’s self and God had become a conversation with, and about, the whole world.”

Taken alongside a certain chronology of an American culture of spirituality, where the memoir collapses with self-help, the talk-show confessional, and the commodification of autobiography, the current popularity of the ex-Orthodox memoir makes plenty of sense. It started with the authority of personal experience–going back to revivalists roaming the countryside, preachers teaching lonesome pioneers to know God’s presence by feeling it, quite literally convulsing and sobbing in river camps, the likes of evangelist Jonathan Edwards almost accidentally ushered in what is now a qualifier of spirituality: the inexplicable, visceral connection to Spirit. Churches and ministers and other filters for revelation removed, the individual’s feelings became proof of divinity. And almost immediately so too did telling this story of connection, wherein an audience experiences, and experientially validates, revelation. “Tears and bodily sensations emerge as signs of pure experience. … The body’s response in fact becomes a sign of divine presence. The narrator’s shift from the cognitive (translatable) events to emotive or embodied events suggests both that the value of the experience is beyond words and created culture,” writes Courtney Bender in The New Metaphysicals: Spirituality and the American Religious Imagination.

The therapy of public confession-to-revelation spins around with the narration of the host to become universal life lesson for the audience (“Oprahfication”), thereby doing good. Spirit in this setting has transmuted into the “sacred self”–that “core of divinity within us all” that drives impulse and intuition. The self is defined by desires, choices; consumer choices, lifestyle choices. The rhetoric of choice is powerful and pervasive. Like Oprah the person, her audience is “capitalist and capital; she is commodity and consumer,” writes Kathryn Lofton in Oprah: the Gospel of an Icon. But in this economy of choice the imminent peril is losing control: There are no limits, there are no rules, there’s no moral code that can’t be bent.

“My instinct is to say that publishing concerns are aware of the sociology of the present, which is obsessed with stories that allow us to fetishize the tyranny of choice,” Lofton, who teaches at Yale, tells me when I ask how the writer of the “coming out as un-religious” story fits into a market perpetually hungry for memoir. “If you look at a few really popular memoirs,” she says—Cheryl Strayed’s Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail (the author hikes over a thousand miles on the PCT alone, escaping grief, a breakup, and heroin addiction), Augusten Burroughs’ Dry: A Memoir (an account of the author’s struggle with and recovery from alcoholism), or Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face(coping with a face disfigured by cancer)—“all very different stories—the common thread is that something controls each of the author’s lives. It’s something they can’t escape, or it’s something they want to get over. At the same time, whatever it is is also a discipline that they can’t let go of (heroin addiction, alcohol, grief). In these stories, getting over these ‘disciplines’ involves extreme ritual.”

Writing the memoir in this case is part of the ritual, a sustained act of self-control, a therapeutic structuring of identity. The irreligious writer is particularly fit for the task and is welcomed by the embrace of American memoir where her confession is highly sellable, her tale of redemption is a service, and audience consumption is the validating context for a new identity.

But then there’s that uncomfortable, transactional element–the feeling that the author is not only selling her life, but that of those around her. This discomfort surfaces in Deen’s book as a constant push and pull between the compulsion to shape an identity by the telling of his story of “becoming” and defending or protecting the world he comes from. There is an absence of outright disappointment in the “cocoon” of Hasidic life, which fails to support him, or derision toward the governance of New Square, which he has more or less expressed elsewhere: “There is something profoundly perverse about a religious community … where a single man acts as autocratic ruler, complete with the trappings of royalty, with extra-judicial powers over the population that include the administering of real physical and psychological pain,” he wrote, in reference to New Square’s rebbe, in the Forward in 2011. And after considerable buildup around the betrothal to his wife, a woman he has not previously seen and is terrified of finding unattractive (even though attraction is not a part of his emotional vocabulary), he doesn’t reveal how he felt when he finally met her.

Without a lot of these details, we miss the village’s place in the spectrum of American Jewish Orthodoxy. In this kind of story, these details, that seem trivial, carry considerable weight when suppressed. Deen’s anger, moral certitude, and bitterness are not absent from his book, but his narrative suffers in his failure to define that world for his readers.

Deen’s ambivalence about his readers—who they are, and how they might feel about the details he allows them—defines his voice in ways that create a degree of distance not strictly in the service of his storytelling. “People are usually very interested in what goes on inside insular communities because of their fascination with what seems mysterious and different,” Deen told Tablet last year. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it, although I don’t always like it. To some degree, there’s a dehumanizing element involved for the writer, and I find it a little discomfiting at times to be lumped into that realm of otherness.”

Yet it is hard for me, writing my own version of my emergence from the land of otherness, not to empathize with Deen’s wariness and his desire to protect people who were once, and even continue to be, his own. On the phone with my mother, we discuss my progress in the search for the guru’s son, and my writing about the spiritual community tucked into the hills outside of Sacramento. My mother knows that I am closer now than ever to asking the questions I set out to ask over a year ago, when I started looking for the best friend I lost, the son of the guru who led the congregation from which my mother and I were unofficially rejected, if there is such a thing as official and rejected when the governance of a place exists in the woolly realm of spiritual virtue. The guru’s son and I, though, were by no means disallowed from seeing each other when I was deemed a poor influence and my mother insubordinate. Time went by. When I realized I had no way of contacting him, I understood too that I had very successfully distanced myself from the community. It had been something like 10 years when I decided I needed to find him again.

“What do you really want to ask him?” My mother says on the phone.

“I want to know if he believes his mother is holy, enlightened,” I tell her. It’s true but it’s not a question I would ask, at least not directly, because it’s not an important question. Either you are the kind of person who needs to ask or you are not. The real question is, why do I not believe, and why does it make me angry to think he might.

I can’t stop myself from writing the story of our time in the community, in the “cult” as my contemporaries call it—jokingly but only because “cult” is a convenient hyperbole, one that makes it easier to admit we were part of something that held us in its power, that we believed and we don’t know why, because we were inspired to belief. Because I felt alone in witnessing madness but didn’t have the words to identify it as madness. I can’t seem to let go of the hurt of feeling tricked by the people I trusted, tricked into wanting the madness. Greater than my need to spew this bitterness is my fear of losing my family in the process. Because through them I know faith. And closeness and connection and home.

When we talk on the phone and my mother asks how the search is coming, I brace for the discussion of whether I think the spiritual community was actually a cult; if I think bad things actually happened there. If I will make her look bad for having belonged. If I will hurt her. And I practice saying, “You have always loved me very well.” And then I continue writing my story.

Genevieve Walker is a Brooklyn-based writer, and the lead web producer at GQ.