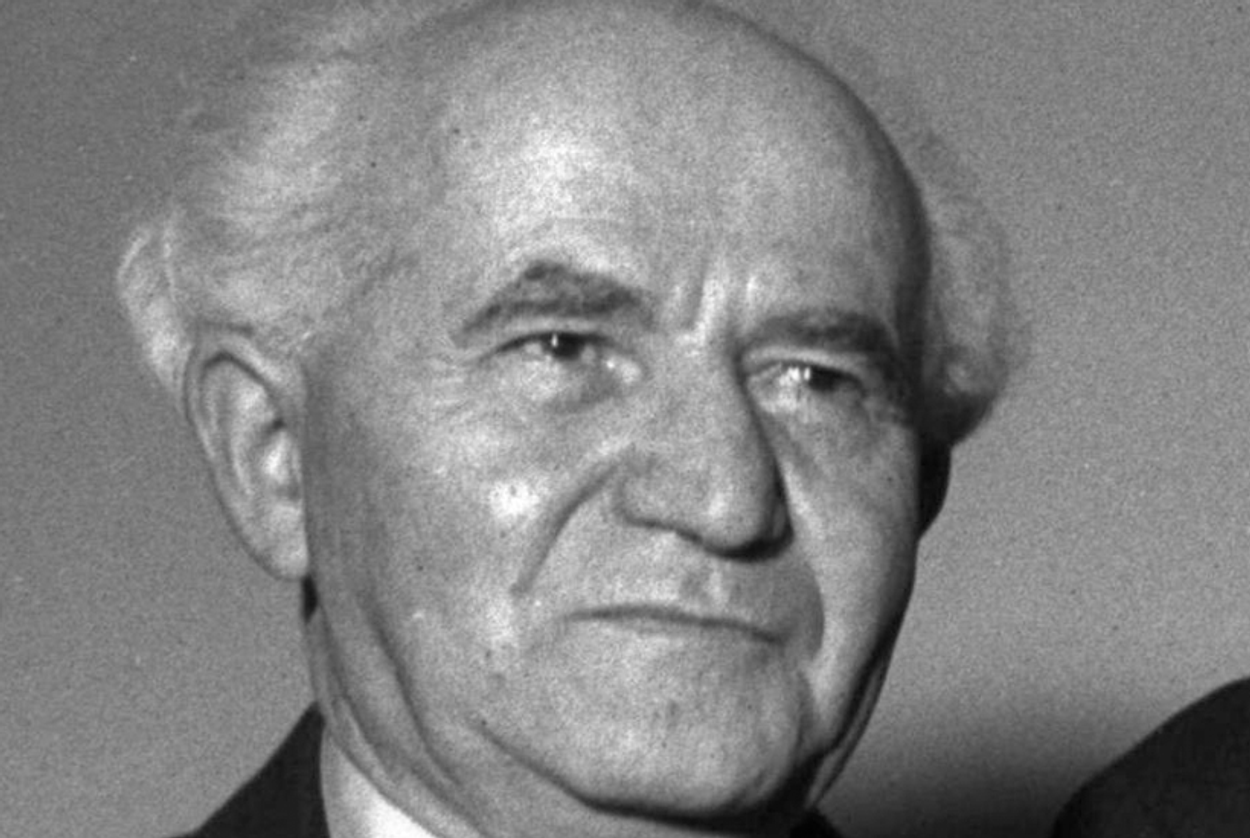

‘Ben-Gurion: Father of Modern Israel,’ by Anita Shapira

An excerpt from a new biography of the great Israeli statesman, David Ben-Gurion

This is a sponsored post on behalf of Yale University Press and their Jewish Lives series.

In April 1936, the Arab Revolt erupted in Palestine. After several days of rioting and the murder of Jewish passersby, Palestinian Arab leaders took charge and announced a general strike that would continue until the Mandatory authorities met three demands: cessation of Jewish immigration, cessation of land sales to Jews, and the handover of government to the Arab majority. With the outbreak of the revolt, the Zionist Executive went on high alert. The most important question was how to prevent the British government from acceding to the Arab demands. The leadership declared a policy of “restraint.” Based on experience, the Jews sought to prevent the rioting from being presented as two-sided, as the authorities had done on previous occasions. Accordingly they would not respond to the Arab terrorism with terrorism of their own—it was the Mandatory government’s job to protect them. At the same time the Zionist leadership demanded that the government recruit Jews as supernumerary policemen, that it not stop immigration, and that it permit the construction of a jetty in Tel Aviv, since Jaffa Port was strikebound and it was impossible to unload goods or disembark immigrants there. For Ben-Gurion, ensuring continued immigration was the core issue of Zionist policy at the time, in Palestine and London alike.

After several years in which the focus of Zionist activity had been in Palestine, the center of activity now reverted to London. The leading personality in the small team housed at 77 Great Russell Street, the Zionist Executive office in London, was Chaim Weizmann. Charming as always, with his extraordinary rhetorical talent and exceptional grasp of the ins and outs of the British political system, Weizmann was the one who presented the Zionist case to the British governmental authorities. He would go on his own to talks at the Colonial Office or unofficial talks with the pro-Zionist lobby. Ben-Gurion, as chairman of the Jewish Agency Executive, went to London to support Zionist activity. He and Katznelson, who was in the office part of the time, formed a sort of Palestine guard ensuring that Weizmann made no mistakes. But they were not told what he said in his tête-à-têtes with the British, with Arab leaders such as the Iraqi prime minister Nuri Sa’id, or with people like Harry St. John Philby, a Briton who had converted to Islam and was a confidant of Ibn Saud, the king of Saudi Arabia. Weizmann kept his British government contacts to himself and hardly ever confided in Ben-Gurion. The Great Russell Street staff were devoted to Weizmann, although they did not always agree with him. Two people in the office who had independent opinions were Blanche Dugdale, Lord Balfour’s niece, known as “Baffy,” and Lewis Namier, a Jew of Polish extraction who was an eminent professor of history at the University of Manchester. They were important members of the office with excellent contacts in the British oligarchy, and they had Weizmann’s trust. They recognized his unreliability and his tendency to make irresponsible statements and leak things he shouldn’t. In his memoirs, Namier wrote: “Much as I loved and admired Weizmann, I suffered severely from his indiscretions, and Baffy and I would sometimes withhold from him even important things if the danger of their being repeated exceeded the possible loss from their being withheld.”

What the British partners in the London office accepted with forbearance, Ben-Gurion found intolerable. At a meeting with Nuri Sa’id, Weizmann, in a slip of the tongue, suggested that the Zionists might be willing to stop immigration for a while in order to facilitate negotiations with the Arabs. Reports of this conversation whipped up a storm in the Zionist camp. In such cases Ben-Gurion was not the easiest or most forgiving partner. He would erupt in rage—often approaching the level of irrationality of “Beware, British Empire!”—and cause chaos in the office. It became increasingly clear to him that Weizmann remained Weizmann, and that he came as a kind of package deal—if you wanted his virtues, you had to bear his shortcomings.

Ben-Gurion needed to obtain not only the trust of the people in the office, but their esteem. Even though he and Namier had similar views, however, his outbursts of rage were not conducive to winning over Namier or anyone else. He was never part of the inner circle that Baffy used to invite to dinner at her home, though she sometimes invited him to join the afterdinner conversation. He did win both admiration and affection from the Oxford-educated Doris May, a young Englishwoman who worked as a secretary at the office. She treated Weizmann with appropriate respect and distance, but she developed a friendliness with Ben-Gurion that deviated from stereotypical British aloofness. It is difficult to imagine Ben-Gurion developing the degree of emotional intimacy and closeness with an educated young Englishwoman that their correspondence reveals.

Their point of contact was a mutual love of classical Greek literature, especially Plato. They exchanged views on writers and books, and she was in charge of sending his book orders from Blackwell’s bookshop in London to Tel Aviv. May and Ben-Gurion remained friends for years, even when their political opinions and approach to the Zionist struggle with Britain diverged. “I told you once, I think, that I could foresee that we should one day find ourselves on opposite sides of a fence,” she wrote him at the end of a letter in which she disagreed with him, “and that when it happened it would make no difference to my friendship for you, because whatever happened I should believe in your utter honesty of purpose.” Ben-Gurion’s friendship with her was some compensation for the frustrations caused by Weizmann and his colleagues, not to mention the representatives of the British government.

It was only after some six months—and the intervention of the Arab kings of Transjordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen—that the Arab strike and the terror ended, making it possible for the British government’s Palestine Royal Commission, headed by Lord Peel, to come to Palestine, hear the claims of both sides, and suggest a new policy. Ben-Gurion appeared before the commission, but only in a minor role. Except for one aphorism—“The Mandate is not our Bible, the Bible is our mandate”—his statement did not make an impression. By contrast, Weizmann addressed the commission with brilliant oratory about six million superfluous Jews in Europe and claimed that Palestine would be able to absorb several million over thirty years. In February 1937, Weizmann visited Nahalal, in northern Palestine, with Professor Reginald Coupland, the commission’s driving force. During their conversation Coupland raised the idea of partition—not cantonization, which is a form of autonomy—but partition into two independent states. Weizmann was ecstatic. So was Ben-Gurion, but he knew that if the Jews were too enthusiastic there would be overwhelming Arab opposition to the idea. Therefore the Jews should play the part of the reluctant bride who must be persuaded until she says yes.

That same month Ben-Gurion drew up a partition plan of his own and presented it for preliminary discussion before the Mapai Central Committee. Knowing his audience, he began with the possibility of a negative change in British policy in the wake of the Arab Revolt. For him the worst-case scenario was for the government to change its policy on immigration, and instead of determining the number of immigrants by the country’s “absorption capacity,” as had been the policy to this point, it would decide arbitrarily how many Jews could enter based on the reactions of the Arabs. Such a politically motivated cap on immigration would force the Yishuv to be an eternal minority. Ending immigration during this period of crisis would make Zionism irrelevant for the Jewish people, as they fought for their life and sought refuge, and the Yishuv would sink into decline. As an alternative he proposed his own plan, with a detailed map. This was the first discussion of a partition plan among Jewish institutions. When Golda Meyerson asked what would happen when there were three million Jews in the small state he had sketched, Ben-Gurion replied: “What will happen after three million Jews come to this Jewish state we shall see afterward. The future generations will take care of themselves; we must concern ourselves with this generation.”

Despite his enthusiasm over the vision of imminent Jewish sovereignty, he accepted the reservations of his colleagues, especially Katznelson, who thought the partition to be proposed by the Peel Commission would probably be far less advantageous than Ben-Gurion’s. Nevertheless, he asserted that when the possibility of a Jewish state, even a tiny one, was on one side of the balance, and on the other the de facto annulment of the pro-Zionist clauses in the Mandate instrument—that is, a moratorium on the national home—he preferred the first. But deep in his heart he did not see partition as the lesser of two evils: for him the vision of a Jewish state that suddenly seemed achievable was a dream come true.

Excerpted from Ben-Gurion: Father of Modern Israel by Anita Shapira, published by Yale University Press. Copyright 2014 by Anita Shapira. Reprinted by Permission.

***

Anita Shapirais professor emerita at Tel Aviv University, where she previously served as dean of the Faculty of Humanities and held the Ruben Merenfeld Chair for the Study of Zionism. Her previous books include Israel: A History, winner of the National Jewish Book Award. She lives in Tel Aviv.