Yiddish Plague Songs

American penny tunes captured the enormity of early 20th-century epidemics

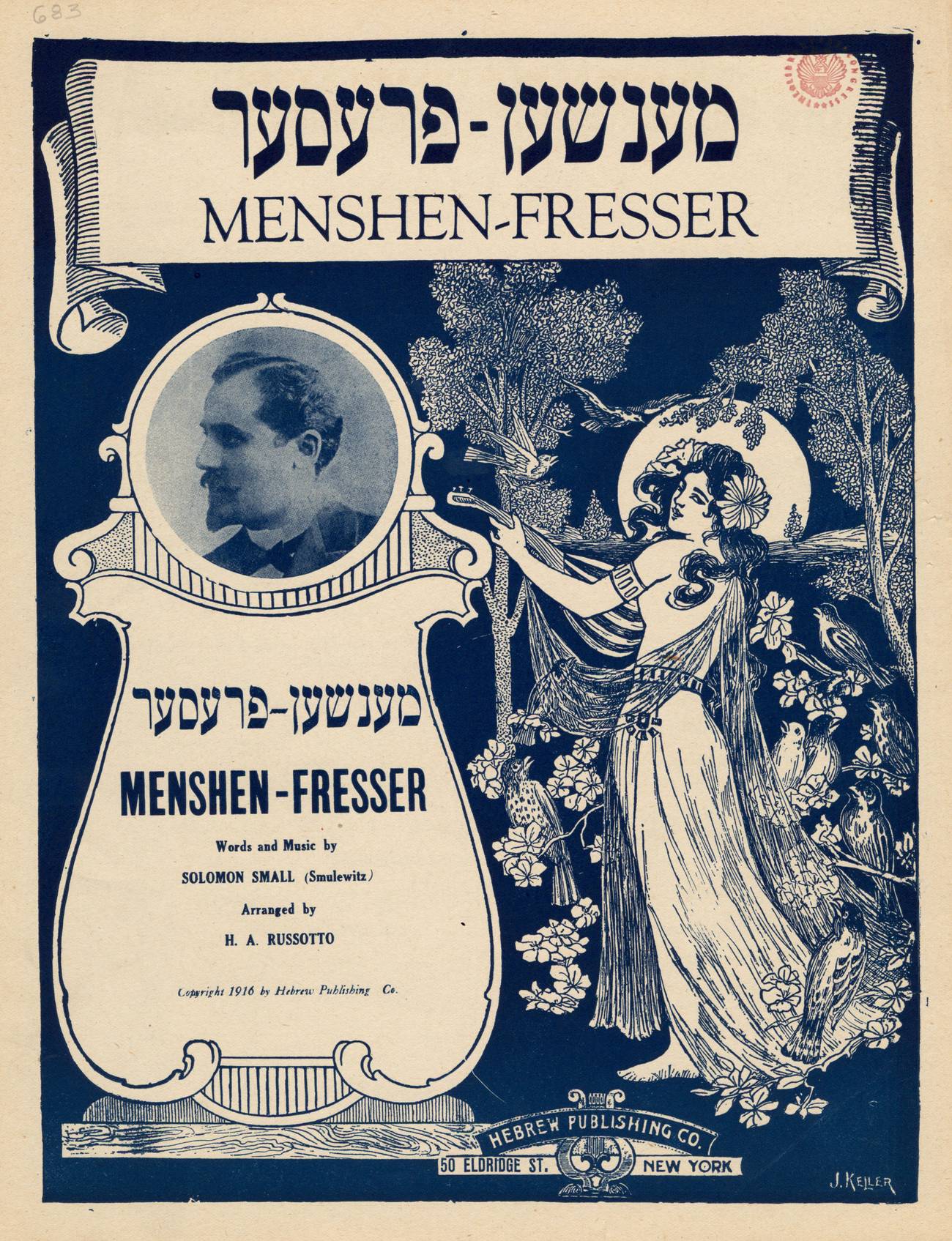

In the rich Yiddish vocabulary of catastrophes, plagues, and epidemics, one vivid phrase descriptive of death caused by widespread disease stands out: “Menshen-fresser.” That is to say that an epidemic is a “human-eater.” Perhaps “human-devourer” would be a better translation: Note the use of the Yiddish word fressen—to eat greedily ; rather than essen—to eat normally.

During the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic, which killed more than 650,000 people in the United States and some 40 million worldwide, this Yiddish phrase crept into popular culture, and into music.

That epidemic, known as the Spanish flu, or “the Spanish Lady,” did not originate in Spain. Its first victims were U.S. soldiers stationed in Kansas who had recently returned from the European battlefields.

According to historian of epidemics John Barry, “By the old naming conventions, the 1918 Spanish flu probably ought to be known as the Kansas flu.” Barry’s history of the epidemic, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History, notes that “ the first identifiable cases arose in Haskell County, Kansas. They soon spread to Fort Riley, from there to other military bases, and then to Europe in troop ships. France, Germany, and Britain had war censors controlling news reports; Spain did not. Spain got the blame.” By not obscuring the truth about the number of victims, Spain—at least in the popular imagination—got the blame.

As COVID-19 spreads, public health officials, historians, and the public are turning to the lessons learned from that great epidemic of a century ago. And students of history, and of cultural reactions to disaster, are uncovering some of the treasures of the past. Yiddish language and culture of the early 20th century provide us with a particularly rich trove.

The 1918-19 Spanish flu, which killed twice as many people as died in the war it followed, was known in Yiddish by many names: grippe, flentsye (a contraction of “influenza”), mageyfe (in Hebrew, plague), and in translation from the English as Shpanke, “the little Spanish one.”

But I find the more poetic “Menshen-fresser,” applied to the sequence of epidemics of the early 20th century—TB, polio, cholera, and influenza—the most powerful.

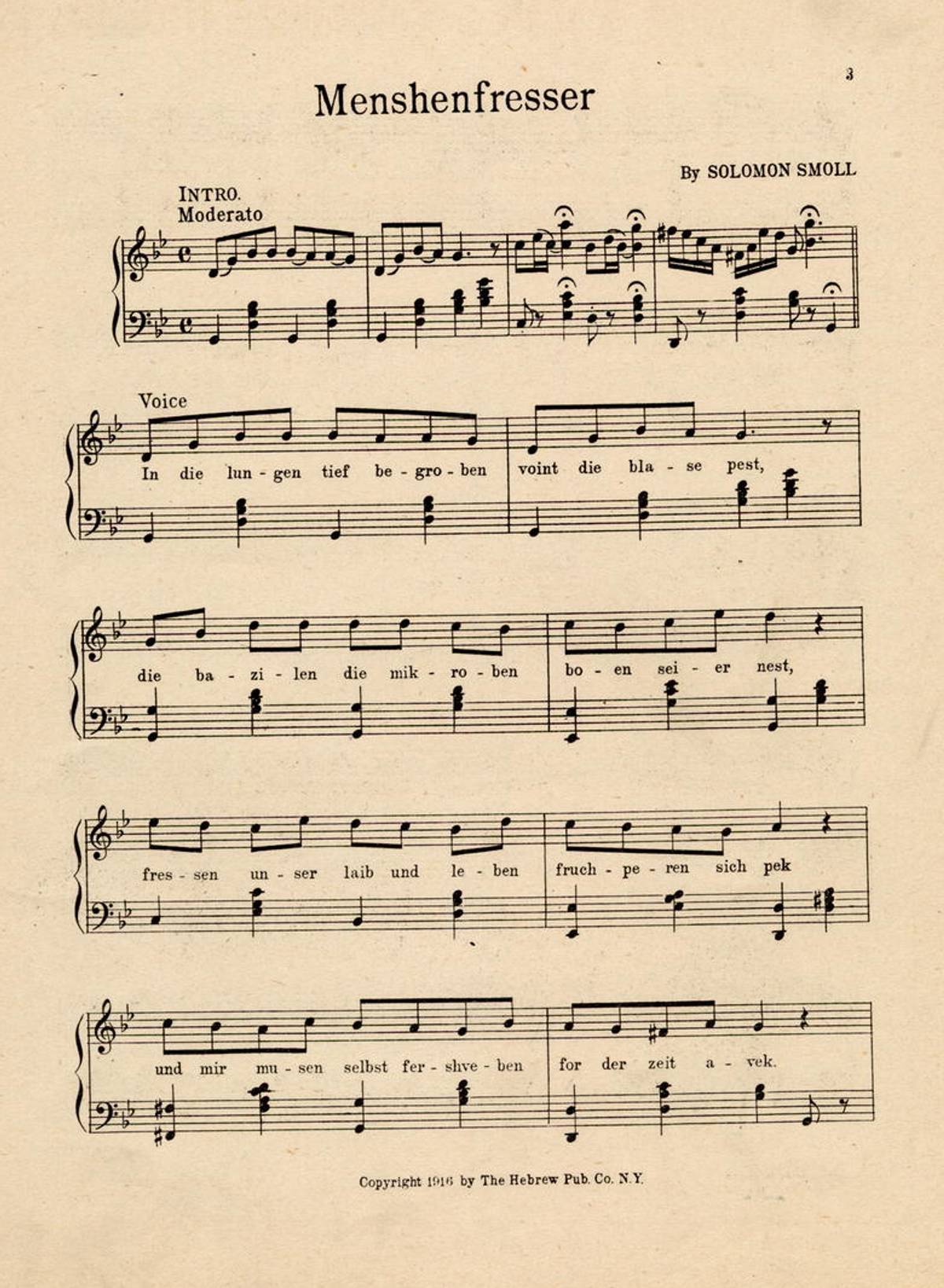

A Yiddish song titled “Menshen-fresser” was one artistic response to the epidemics that preceded and followed World War I. The song’s poignant lyrics, written by Shlomo Shmulevitz (Solomon Small) ask:

Mikrobn batsiln vos vilt ir?

Zogt vemes shlikhes derfilt ir?

Ir frest di korbones gor on a rakhmones,

in bliyende lebn nor tsilt ir!

Microbes, bacilli, what do you want?

Whose mission are you carrying out?

You gobble the victims mercilessly,

you aim only at blooming lives

Another terrible epidemic goes from land to land

With the speed of a blazing fire from a piece of burning wood.

It poisons little children, infants at the breast,

It robs fathers and mothers of their hearts’ cheer.

“Menshen-fresser” and many other Yiddish popular songs, were long forgotten until they were discovered by independent researcher Jane Peppler, a performer of Yiddish theater music. Peppler has transcribed and performed hundreds of these musical gems. Her recordings are available on CD and online at yiddishpennysong.com.

In the early 1900s, TB was the leading cause of death in New York City and the disease’s frequency was greatest among the poor, including the Jewish poor. “Kinder Mageyfe” (children’s plague), another Yiddish song of that era , mourns the crippling of thousands of children in New York and its environs. The song opens with these lines:

fathers and mothers are crying

fear lurks in every house

thousands of children are being crippled ...

who can stand the sight of children unable to stand on their feet?

The epidemics orphaned children and left them without care or support. While children of the victims may not have caught the disease themselves, they were left without parents to care for them. That is the story told in one of the most poignant of these songs, “Di yesomim” (The Orphans). In this song we hear of a poor immigrant couple. First the mother dies of the flu, then the father is diagnosed with TB and is sent to a sanitarium.

The parents are recent immigrants and have no family in the city. No part of the social network—unions, settlement houses—steps up to take care of the children—and they soon die of neglect. The lyrics open with a Yiddish cry of woe:

Oy vey iz mir! Ver? Ver vet nemen tsvey yesoymim

Vos zaynen geblibn on a heym?

Oy vey iz mir! Ver? Ver vet af zey rakhmones hobn

un nemen tsvey yesoymelekh?

Woe is me! Who will take two orphans

who have been left without a home?

Woe is me! Who will have mercy on them

and take two little orphans?

Listening to these songs a century later can give us a sense of the enormity of the epidemics of the early 20th century. As we face the consequences of the spread of COVID-19 we can endeavor to prevent it from becoming a “menshen fresser” as hungry as its predecessors.

Shalom Goldman is Professor of Religion at Middlebury College. His most recent book is Starstruck in the Promised Land: How the Arts Shaped American Passions about Israel.