Yiddishkeit

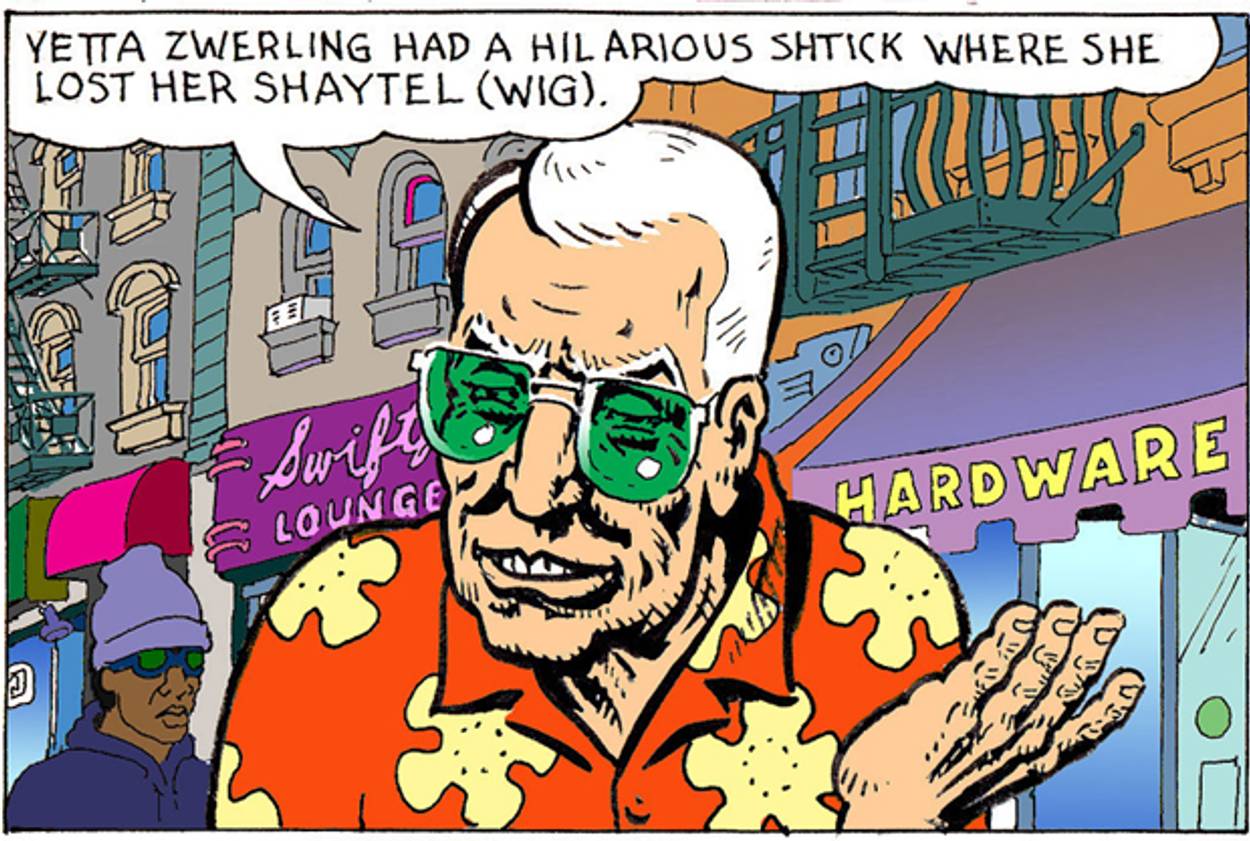

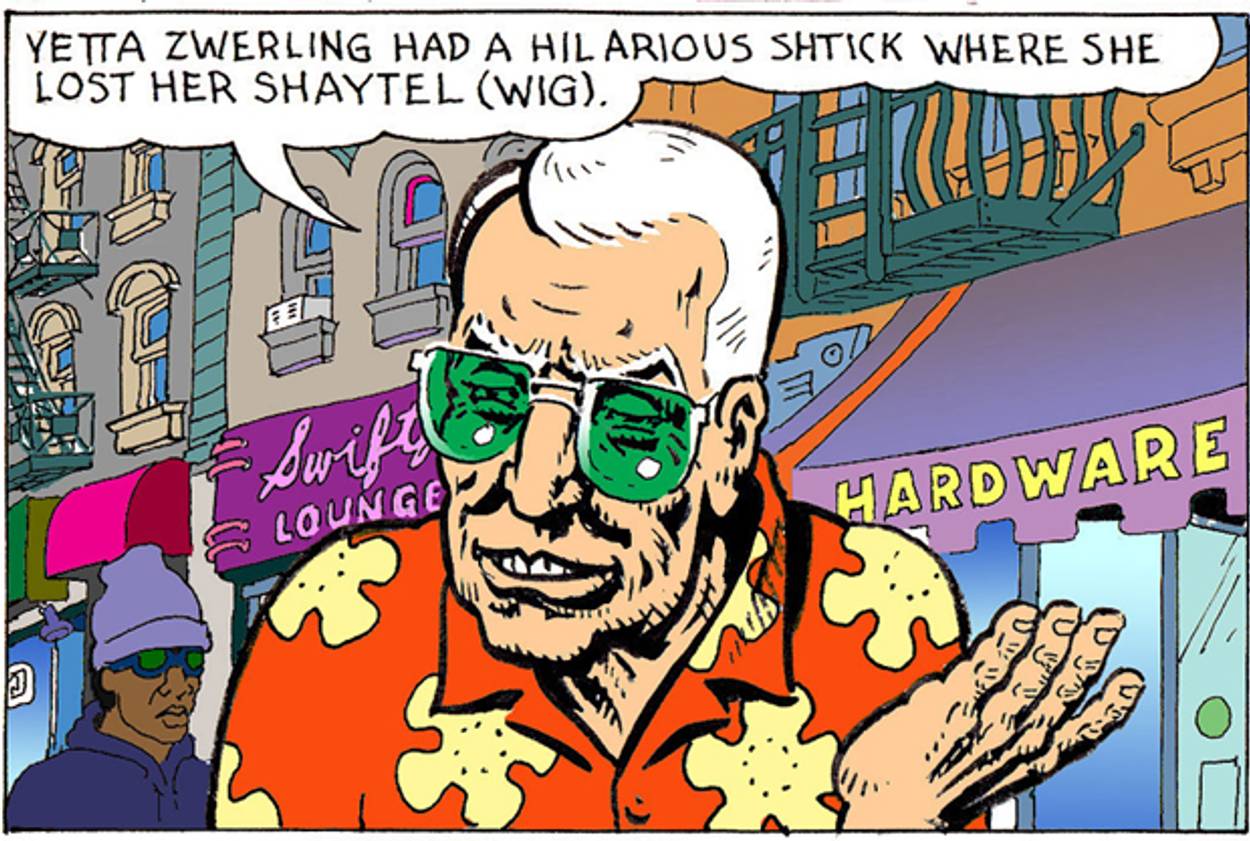

The last fully realized work by Harvey Pekar illuminates the bluntness and delight of American Yiddish in the last century. A new excerpt.

Perhaps the greatest difficulty in trying to describe “Yiddishkeit” to an English-speaking audience, as this book attempts to do, is that there is really no English equivalent for the word. “Yiddish culture” comes close, but Yiddishkeit is so large, expansive, and woolly a concept that culture may be too narrow to do it full justice. “Jewish sensibility” comes closer still because it internalizes the notion of Yiddish, places it in the head as well as on the stage and the page, but sensibility is itself a rather loose and elusive idea and within Yiddishkeit there are several sensibilities that, while closely connected, are still not congruent. In effect, Yiddishkeit isn’t a thing or even a set of things, an idea or a set of ideas, which may explain why a book about Yiddishkeit is itself so sprawling, kaleidoscopic, disjointed, eclectic, and just plain messy. You really can’t define Yiddishkeit neatly in words or pictures. You sort of have to feel it by wading into it.

The feeling, of course, is largely a function of language. Yiddish may be the most onomatopoeic language ever created. Everything sounds exactly the way it should: macher for a self-appointed big shot, shlmiel for the fellow who spills the soup and shlmazel for the poor guy who gets the soup spilled on him, putz for an active louse, shmuck for a hapless one (as in “poor shmuck”), shnorer for a freeloader, nudnick for a pest. The expressiveness is bound into the language, and so is a kind of ruthless honesty. There is no decorousness in Yiddish, nor much romance. It is raw, egalitarian, vernacular.

That is why, even though there was, as Harvey Pekar makes clear in these pages, a vibrant Yiddish literature, the whole idea of a literature may have been inimical to the very spirit of Yiddish. Sentiment, sensationalism, and formula—all of these were natural to a language that was focused on the here and now rather than on airy philosophical discourse, on the forcefulness of expression rather than on nuances, on brutal truthfulness rather than on fine emotions. Yiddish is a blunt instrument. That is its real charm, not the phony whimsy that Pekar so detests in the work of Isaac Bashevis Singer, perhaps the most famous Yiddish writer.

Instead of great works, the language’s primary legacy is not only the Yiddishisms sprinkled into English for flavor or the subversive candor that impregnated American entertainment through Jewish comics but also the very democracy of Yiddish—its stubborn plebeian pride. Yiddishkeit seems to luxuriate in its own lack of elegance and its own marginalization, which is why a book of comics art, another outsider form, seems especially appropriate to describe it and why a wry shlump like Pekar seems an especially apt coauthor.

Yiddishkeit is abrasive. It is an attitude of challenge just as Yiddish is a language of challenge. As this book amply demonstrates, Yiddish artists were always attacking the status quo, and it is certainly no coincidence that many of these Yiddish artists, not to mention many grassroots Yiddishers, were political leftists. By the same token, the artistic and political Jewish establishments were afraid of Yiddish—afraid of the way it seemed to bulldoze right over politesse. Even the state of Israel reviled Yiddish, ostensibly for fear it would override Hebrew, and, as you will read, there were times when Israel outlawed the Yiddish theater. In effect, though, the real fear of Yiddishkeit was that it was too Jewish, too insular, too much an expression of the loud, wild, lively Jewish hoi polloi whom high-born Jews found so offensive. Who could imagine a state where the citizens spoke Yiddish?

Now that Jews have been largely assimilated into America, Yiddishkeit may seem both anachronistic and nostalgic here. Many Jews of my generation will no doubt remember, as I do, their grandparents speaking Yiddish when they didn’t want the children to know what they were talking about. As the European-born and then the first American-born generations passed, they seemed to take Yiddish with them. And yet Yiddishkeit has managed to survive, if just barely, not because there are individuals dedicated to its survival, though there are, but because Yiddishkeit is an essential part of both the Jewish and the human experience.

Neal Gabler, a senior fellow at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, is an author, cultural historian, and film critic. This is excerpted from Yiddishkeit: Jewish Vernacular & the New Land, edited by Harvey Pekar and Paul Buhle, published by Abrams ComicArts. Introduction copyright © Neal Gabler, 2011. Illustrations copyright © their respective creators, 2011. Reprinted by permission.

Neal Gabler, a senior fellow at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, is an author, cultural historian, and film critic.