A Mother’s Kaddish: Mourning for My Son, From the Women’s Section

After my child died, I reconnected with God through prayer—which is the point of Kaddish, on both sides of the mechitza

This essay is excerpted from Kaddish: Women’s Voices, edited by Michal Smart and Barbara Ashkenas, which won a National Jewish Book Award last week.

It is hard to believe that it is four years since Nathaniel’s passing. I still feel his presence throughout the day and miss his warm, smiling face and upbeat outlook. The name Nathaniel means “gift of God,” and that is what he was. He woke up almost every day with a smile, eager to greet the world. An optimist by nature, the words “no” or “can’t” were not a part of his vocabulary. He viewed life as a series of opportunities to explore and experience. Although never seeking the limelight, he always desired to be where the action was. He loved people and places, and was always ready to try something new. Although Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, a progressive deteriorative disease, reversed the normal course of his life, he managed to enjoy all that he could participate in.

From the time of Nathaniel’s diagnosis at age 6 he began to decline. He lost his ability to walk at age 8 1/2 and by his early teens was fast becoming a quadriplegic. Instead of being a mother who slowly let her child grow toward independence, I was forced by necessity to be a mother who had to involve herself in every aspect of my child’s life. From showering, to toileting, to dressing and feeding, as Nathaniel deteriorated his every function became the responsibility of those who loved him most, his family.

With his death at age 21, on that cold day in April, my constant physical orchestrations ended, but my emotional desire to care for my son did not. The desire to do for one’s child does not die with that child.

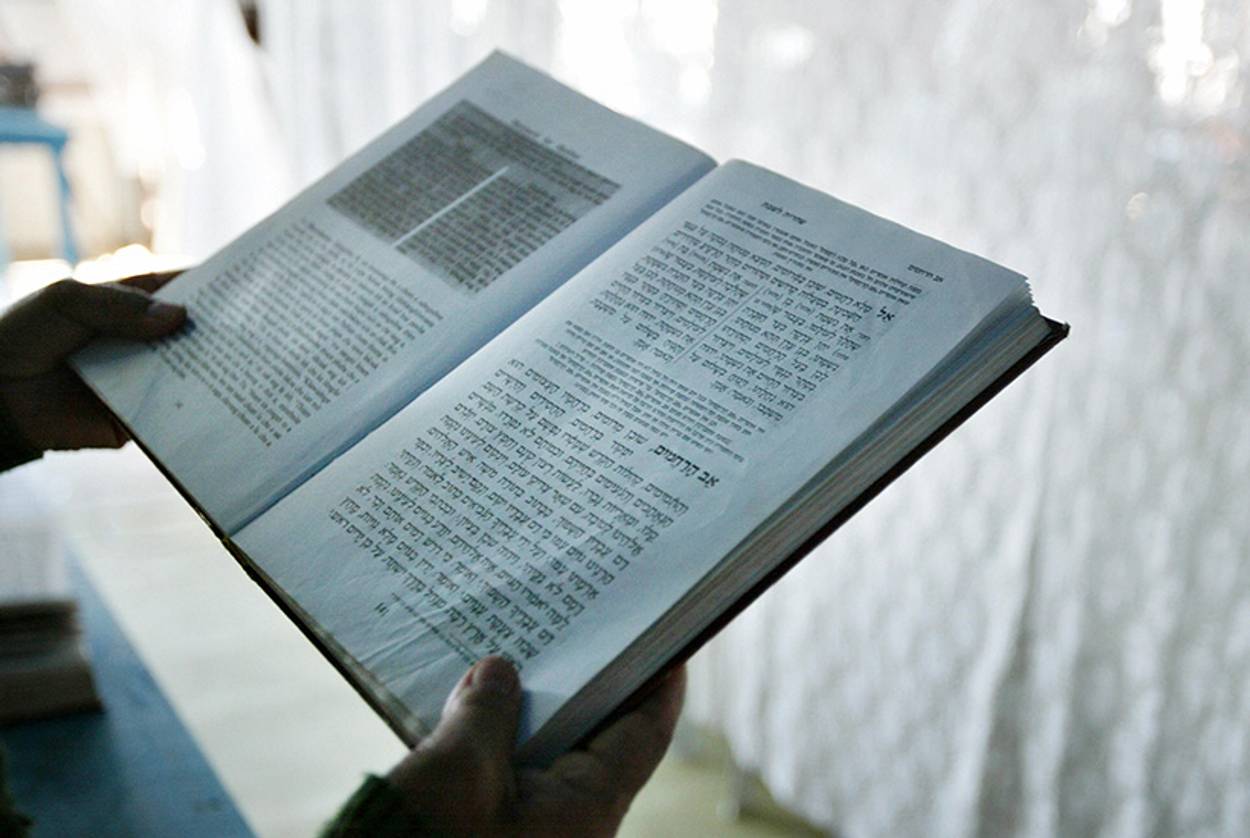

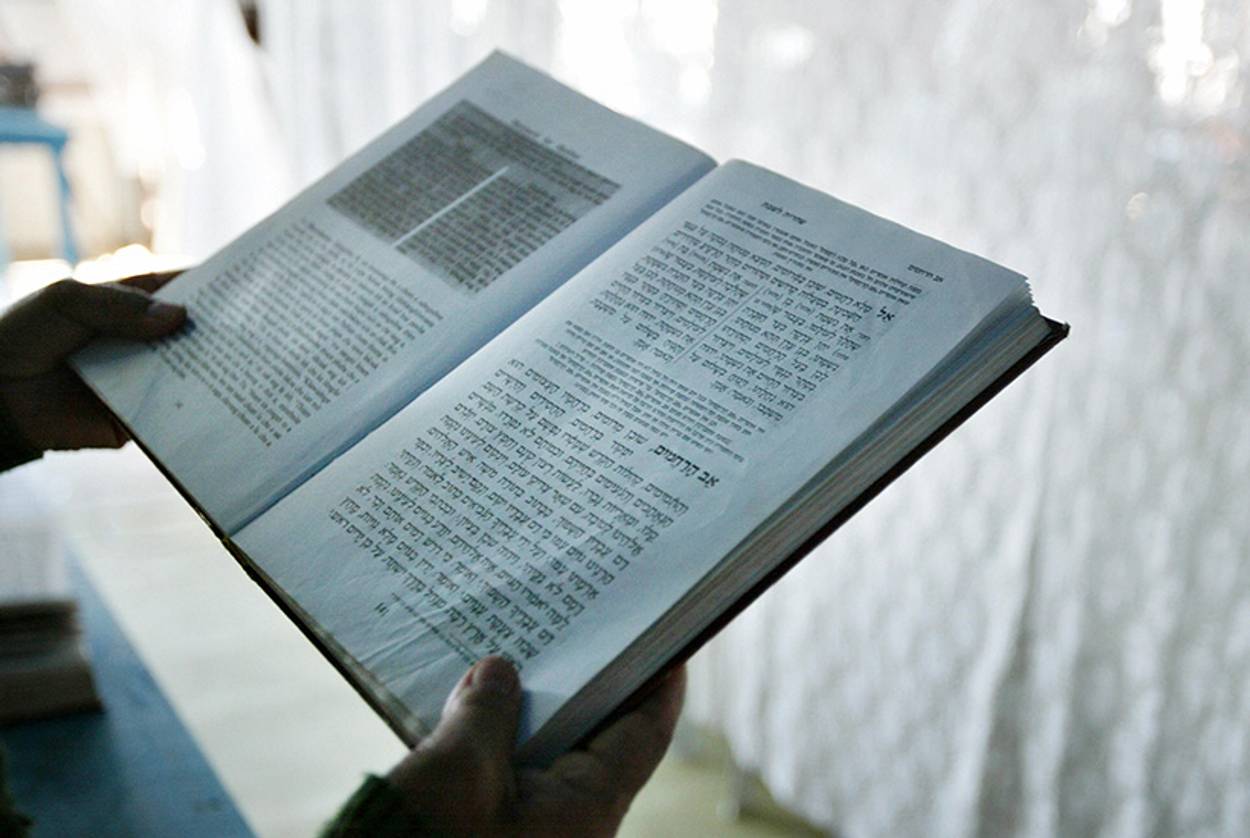

When Nathaniel passed away, we in his immediate family were obligated to say Kaddish for the shloshim, the thirty-day period of mourning. My husband, Ruvan, my other children, Jonathan and Jackie, and I were steadfast in taking on this chiyuv (halachic obligation). After all, didn’t Nathaniel deserve this last act of devotion? As the days of that first month dwindled, Ruvan told me that he wanted to take on the obligation of saying Kaddish for the full eleven months. The minute he said that, I too knew that I wanted to take on this longer obligation, as well. Had Nathaniel had the zechut, the privilege of living a full healthy life, chances are he would have had children to say Kaddish for him. Since that was not to be his fate, who would be more appropriate to say Kaddish for him than his mother? I carried him in my womb, I birthed him, and I orchestrated the life he led. For his 21 years our lives—his and mine—were inextricably bound together. It was out of a profound sense of loss that I took on the commitment to say Kaddish.

At that moment, I don’t think I fully grasped what saying Kaddish would really mean. Yes, I knew it was said at three different prayer times every single day. Yes, I knew I would have to say it for close to a year. But no, I don’t really think I thought about how difficult it would be for a person like me who is, despite the best of intentions, perpetually tardy. All I knew was that I was grieving for almost every aspect of my son’s short life and I wanted desperately to be able to connect to him. Kaddish was a means for me to continue doing for Nathaniel.

Since I was a little girl, I was told that there are many levels in heaven and that when a Kaddish is recited for a loved one, that neshama gets to move to the next level. Although I’m not quite sure what I presently believe, I do know that hearing “his neshama should have an aliyah” was quite comforting to me. It helped to make that nebulous void of death feel like a slightly more tangible, cause and effect relationship. If people heard my Kaddish they would say “Amen” and help to make Nathaniel’s ascension in heaven happen.

I most often said Kaddish at my Modern Orthodox synagogue on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I was not the first woman in my congregation who chose to say Kaddish and I am certainly not the last. At one point, we had as many as six women saying Kaddish, some out loud, some in a low voice, according to the way they are comfortable, not dissimilar from the ways different men say Kaddish. For the most part I felt comfortable saying it there and felt that the men as well as other women answered, “Amen.”

Nonetheless, certain customs of the daily service began to grate on me. For example, in Shacharit, our congregation has the shaliach tzibbur recite the Birchot HaShachar (morning blessings) out loud, to which the congregation answers “Amen.” At the point where he recites the blessing for “God having not created me a woman,” the women on the other side of the mechitza (divider) are supposed to say silently to themselves the blessing for “God creating me according to His will.” I have learned and fully understand why that blessing is there, that it refers to the fact that according to tradition men are obligated to do more mitzvot than women are and for that they are thankful. But the truth is, despite understanding where the blessing comes from, it is insulting to hear a hearty refrain of “Amen” to the line praising God for not making one a woman, day in and day out. In a religion where it is customary to cover the challah bread at a Friday night Shabbat meal during Kiddush so as not to embarrass or make the challah feel jealous while the wine is being blessed first, I couldn’t help but wonder how a community could not devise a method where the man leading the service would take note before he starts if there is a woman present, and if so, he could say this blessing silently to himself. If we demonstrate compassion for an inanimate object like a loaf of bread, why can’t we show more sensitivity toward women choosing to pray with a daily minyan?

I occasionally encountered problems saying Kaddish when I traveled to a different minyan. One time in Florida, I davened at a minyan set up for Yeshiva boys, and I was the only mourner. Midway through my first Kaddish, I realized no one was saying “Amen” to my Kaddish. By the time I finished my second Kaddish, I turned to the men on the other side of the mechitza and said out loud, “Great, not one of you is going to say amen to my Kaddish?” They would not. Although I felt grateful that they didn’t try to drown me out (as happened to me once in a Haredi synagogue in upstate New York), I felt shocked and angry that high school age yeshiva boys couldn’t display enough kavod ha-briyot, basic human respect, to muster an “amen” to my Kaddish. After all, what could be so wrong about uttering the word “amen” when a fellow Jew praises God? The friend I was visiting contacted the principal of the yeshiva, who promised to give them a talk the following day on the laws of answering a person’s Kaddish. I hope they learned a life lesson!

The controversy I sometimes encountered prompted me to research the halachic discourse regarding women saying Kaddish. I was grateful that JOFA (Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance) had collected sources on the subject and made them readily available on its website. I was bolstered by the long history of rabbinic responsa that permit women to say Kaddish. Interestingly, Rabbi Moshe Leib Blair said that saying Kaddish is an integral part of mourning, for which a woman is obligated, rather than an integral part of tefillah b’tzibbur, public prayer, from which she is exempt.

Despite the upsets, as the year passed, my inner dialogue with God grew through prayer. I realized that throughout Nathaniel’s illness I had been so angry with God that essentially I had stopped praying. My yearning for a miracle that would stop his slow steady deterioration was so strong that it rendered me speechless for prayer. But as the year of saying Kaddish wore on, I felt a level of comfort from the steadiness of the repetition of prayer. Eventually, I was able to reconcile myself to the concept of a “merciful God,” a formulation that I had a great deal of difficulty with from the time of Nathaniel’s diagnosis. Despite being aware of the abundant blessings that I had in my life, throughout his illness I kept feeling that if our omnipotent God were truly merciful, He would create a miracle and cure Nathaniel’s disease. Over the course of my year saying Kaddish, I finally internalized that which I always knew to be true. We are all here on this Earth for only a moment, and although Nathaniel’s moment was especially brief, at least he was given the two most wonderful caring siblings and fabulous father that any person could ever want, and the love and devotion of his entire family. I finally understood that the quality of his life made it a merciful one.

Through tefillah b’tzibbur, and participating in it by saying Kaddish out loud and having it responded to, I was able to reconnect to a relationship with Hashem that I wasn’t sure that I would ever regain. I think that in a fundamental way that is the very purpose of tefillah, whether one is a man or a woman. I urge all of you to consider that regardless of which side of the mechitza one is on, people who come to daven are striving to find their connection to and peace with Hashem, equal in intent, equal in merit and equal in importance.

Excerpted from Kaddish: Women’s Voices, edited by Michal Smart and Barbara Ashkenas. (c) Michal Smart and Barbara Ashkenas. Reprinted courtesy of Urim Publications.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Shelley Richman Cohen became an advocate for inclusion of Jewish children with special needs starting with the diagnosis of Duchene Muscular Dystrophy of her eldest son, Nathaniel. She continues to be active in the field of disabilities advocacy as a public speaker and as a board member of day schools and Jewish organizations.

Shelley Richman Cohen became an advocate for inclusion of Jewish children with special needs starting with the diagnosis of Duchene Muscular Dystrophy of her eldest son, Nathaniel. She continues to be active in the field of disabilities advocacy as a public speaker and as a board member of day schools and Jewish organizations.