In the Shadow of the Divine, Reaping Unintended Benefits at the Edges of the Law

Daf Yomi: A closer look at the Holy of Holies provides a fascinating illustration of how the rabbis of the Talmud read the Bible

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

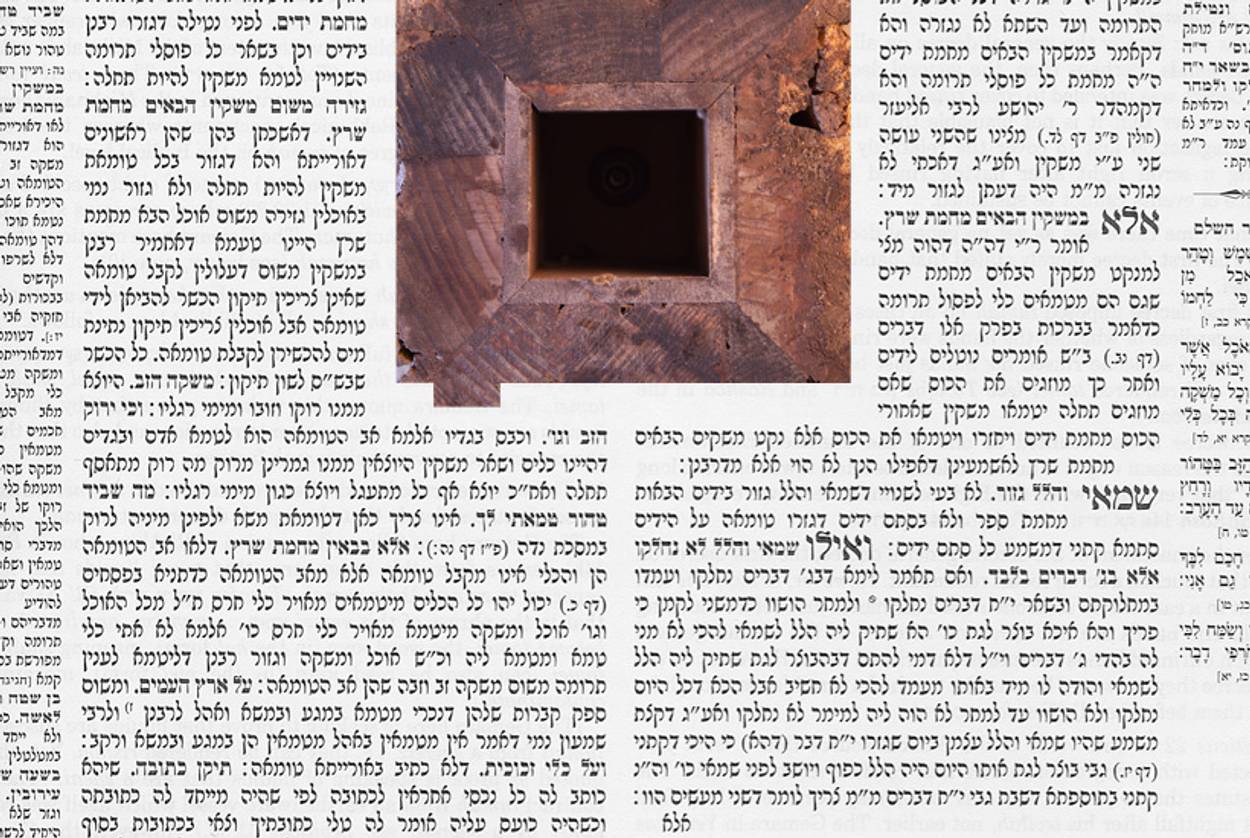

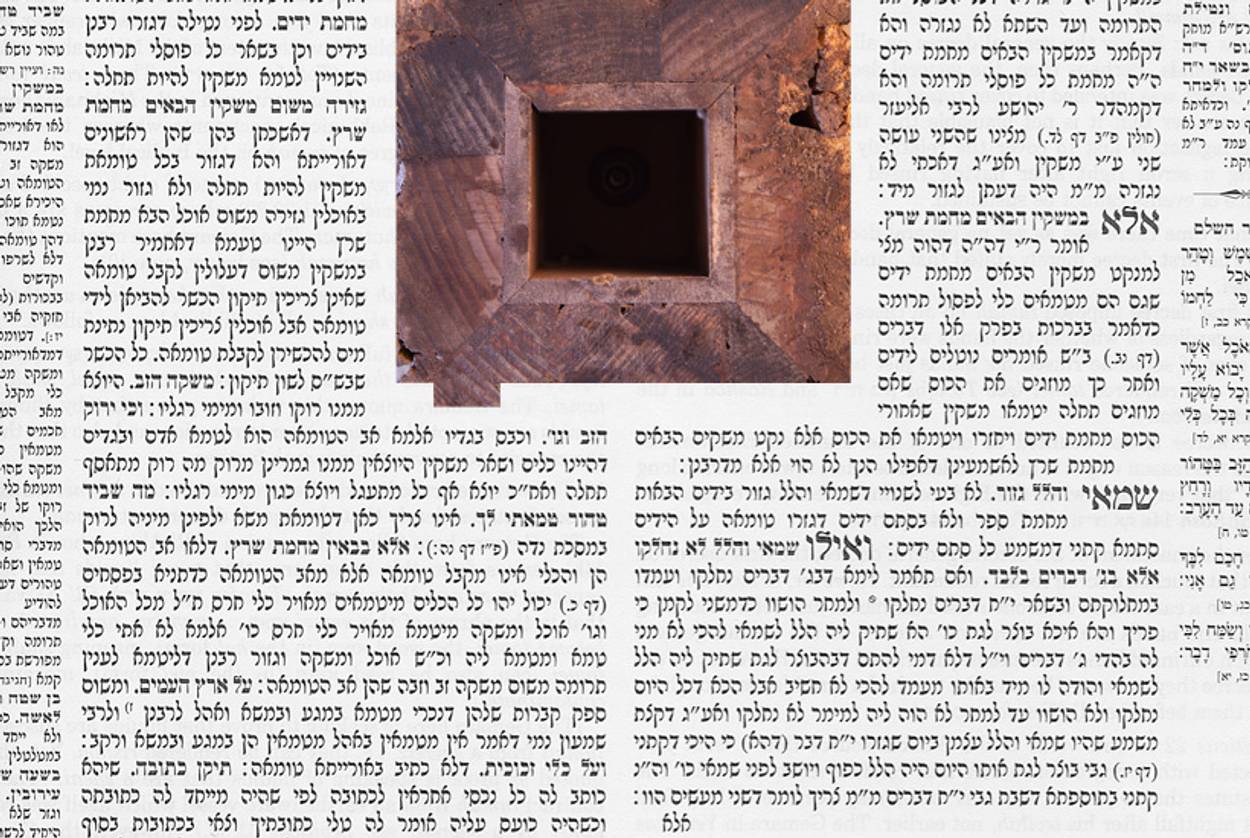

Last week, in its discussion of purity and impurity, the Talmud showed how the rabbis kept the memory of the Temple alive, centuries after it had been destroyed by the Romans. This week’s Daf Yomi reading featured another kind of reminiscence of the Temple—a glimpse of its humbler, more practical side. The Temple was arranged as a series of concentric courtyards, each one holier and more restrictive than the last, until at the center one reached the Holy of Holies. This was the empty room where God’s presence dwelled and that no one was allowed to enter except the high priest once a year, on Yom Kippur. But even the most sacred building is still made of wood and stone, which means that from time to time it will need to be repaired. What happened when the Holy of Holies needed to be fixed up or given a new coat of paint?

The answer is found in a mishnah cited by Rava on Pesachim 26a. “Hatches were opened in the upper story of the Holy of Holies structure, through which they would lower the craftsmen in crates, so that their eyes should not feast on the Holy of Holies structure.” Evidently what this means is that the workmen would descend in a box that was closed on three sides, so that they could only look straight ahead, at the part of the wall they were meant to be working on. Lowering them through the roof was considered preferable to letting them walk through the door, which was the usual means of entry. This follows the principle, which we saw invoked on several occasions in Tractate Shabbat, that if you do something forbidden in a nonstandard fashion, the law is not as clearly infringed.

How did the rabbis get from the subject of disposing of chametz to this bit of remembered Temple lore? The connection lies in the problem of whether it is permitted, as a general rule, to derive any kind of benefit from something that is legally prohibited. The discussion begins at the start of Chapter 2 of Pesachim, where the Mishnah offers a ruling about permissible uses of chametz on Passover. It is, of course, forbidden to eat leavened bread during the week of Passover, and we have previously seen that the rabbis extended this prohibition to include the afternoon of the day before the holiday starts. But are you allowed to make use of chametz in other ways? For instance, can you sell it to a non-Jew, who will not destroy it before Passover begins? Or can you use it as a fuel for a fire?

The Mishnah says that, as long as it is permitted to eat the chametz—that is, until the sixth hour of the day before Passover—it can also be sold to a non-Jew. After that point, when eating it is prohibited, “its benefit is forbidden,” so that one cannot even “fire an oven or stove with it.” This seemingly simple rule gives rise to a very long and complicated discussion in the Gemara. Why, the rabbis ask, does the Mishnah extend the ban on chametz from eating it to all forms of benefiting from it? What is the biblical basis for this law? After all, in Exodus 13:3 God tells Moses: “Remember this day, in which you came out from Egypt, out of the house of bondage; for by strength of hand the Lord brought you out from this place; there shall no leavened bread be eaten.” How does “eaten” get interpreted to mean “used in any way”?

The reason, we learn, comes from a general rule of biblical interpretation, attributed to Abahu: “Wherever it is stated one shall not eat, or you shall not eat, both a prohibition against eating and a prohibition against benefit are indicated, unless Scripture specifies otherwise.” For the next several pages, other Amoraim cite a number of biblical verses meant either to support or to challenge Abahu’s rule. In the process, they offer a fascinating illustration of how the rabbis of the Talmud read the Bible.

Often this means interpreting the text in ways that might seem counter-intuitive or downright perverse. But there is a set of strict interpretive rules that govern the rabbis’ practice, so that even when they seem to be reading against the grain of the Bible, they are still doing so in a rational, rule-governed way. One such rule, repeatedly cited in this discussion, is that every word in the Bible is put there deliberately to teach a specific law. As Rav Ashi says in Pesachim 24b, “Whenever it is possible to expound a new law from a verse, we expound it.”

This idea follows logically, even necessarily, from the belief that the Torah was given by God. To a secular reader, the Torah’s many contradictions, repetitions, and ambiguities are best explained as a product of the editing together of many different source texts, written by different people at different times. To the rabbis, every word was God’s, and God does nothing carelessly; there is a reason behind every one of his verbal choices, which it is our duty to figure out.

A case in point comes when the rabbis consider the biblical prohibition on eating meat that has been cooked in milk. This is one of the most famous Jewish laws, yet if you look at Deuteronomy 14:21, you find that the verse does not actually prohibit eating such meat at all: “You shall not eat of anything that dies of itself … for you are a holy people unto the Lord your God. You shall not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk.” What the text prohibits is “seething,” that is, boiling or cooking—it doesn’t say a word about eating! How, then, do we know that in addition to not cooking an animal in its mother’s milk, we also can’t eat such meat cooked by someone else—say, by a non-Jew?

That’s easy, we might reply—just look at the context. The verse starts out by prohibiting eating the meat of any animal that dies naturally, without being slaughtered. Doesn’t it make sense that, when the Torah goes on to mention another category of meat, it is because that too is prohibited? What would the sense be of prohibiting the cooking of meat without prohibiting the eating of it?

But this is not the way the rabbis read the Bible: To them, context and implication are less convincing than specific verbal indications. That is why they seize on the phrase “for you are a holy people.” That phrase can be connected, by the kind of verbal parallelism we have seen the Talmud use before, to another passage about food in Exodus 22: “And you shall be holy men to me, and meat torn in the field you shall not eat.” Just as the word “holy,” in Exodus, is juxtaposed with a prohibition on eating, so “holy” in Deuteronomy is also meant to signal a prohibition of eating. On this slender foundation rests the whole enormous legal and practical apparatus of kashrut.

The Talmud goes on to consider other examples of “deriving benefit” from things that are prohibited in themselves. In case of a life-threatening illness, Rabbi Yaakov says, we may use even a prohibited item to save a person’s life—presumably this would include feeding them unkosher meat, if for some reason it was absolutely necessary. There is just one exception to this rule: The wood of an asheirah cannot be used for medicine, even to save a life. An asheirah was a tree worshipped by pagan Canaanites, and using it any way is not just infringing a law; it is blaspheming against God. For this reason, it violates the key commandment, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might.”

The problem of the workmen in the Holy of Holies is also considered as a case of “deriving benefit” from something prohibited—in this case, the benefit of getting to look at the holiest spot in the world, ordinarily prohibited to everyone but the high priest. Indeed, the rabbis wonder whether it might not be a kind of sin to derive any kind of pleasure from the Temple, even by looking at its decorations, listening to the music played there, or smelling the incense. This seems strange: Surely these things were designed specifically for the pleasure and awe of the Jews who worshipped in the Temple? Why build a beautiful structure and fill it with music and perfume if people are not allowed to enjoy it?

But again, this is not how the rabbis look at things. To them, the Temple and everything in it—the priests burning incense, the Levites chanting psalms—are God’s and God’s alone. All the Temple rituals are performed because God commanded them, and God is their intended audience. For a person to enjoy them might thus be considered a case of deriving benefit from a sacred object, a sin known as me’ilah.

Indeed, the rabbis even wonder whether the great sage Yochanan ben Zakkai committed a sin when he sat in the shadow of the Temple walls to expound the Torah. Isn’t the shadow, too, a benefit from the Temple? But another rule for the Amoraim is that, if a Tanna did something, it is presumptively legal; and Rava finds a way to justify Yochanan’s practice. “The Sanctuary,” he explains, “is made for what is inside of it.” That is, the intended benefit of the Temple’s walls is to shelter what’s inside it; the shadow cast by those walls is an unintended benefit, and as we have seen, using something in an unintended fashion avoids breaking the law. There is something poetic about this idea, and it could even become a metaphor: We are all dwelling in the shadow of the Divine, living on the unintended benefits of His presence.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.