Archaeology Without Ruins

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi,’ ancient Talmudic rabbis look for the First and Second Temples without stones or relics to guide them

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

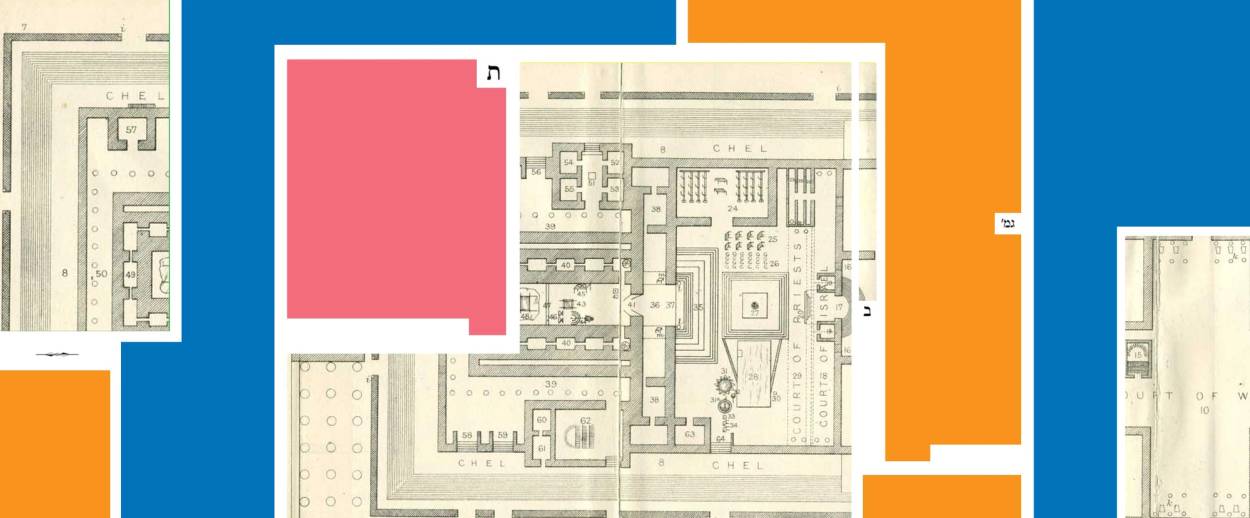

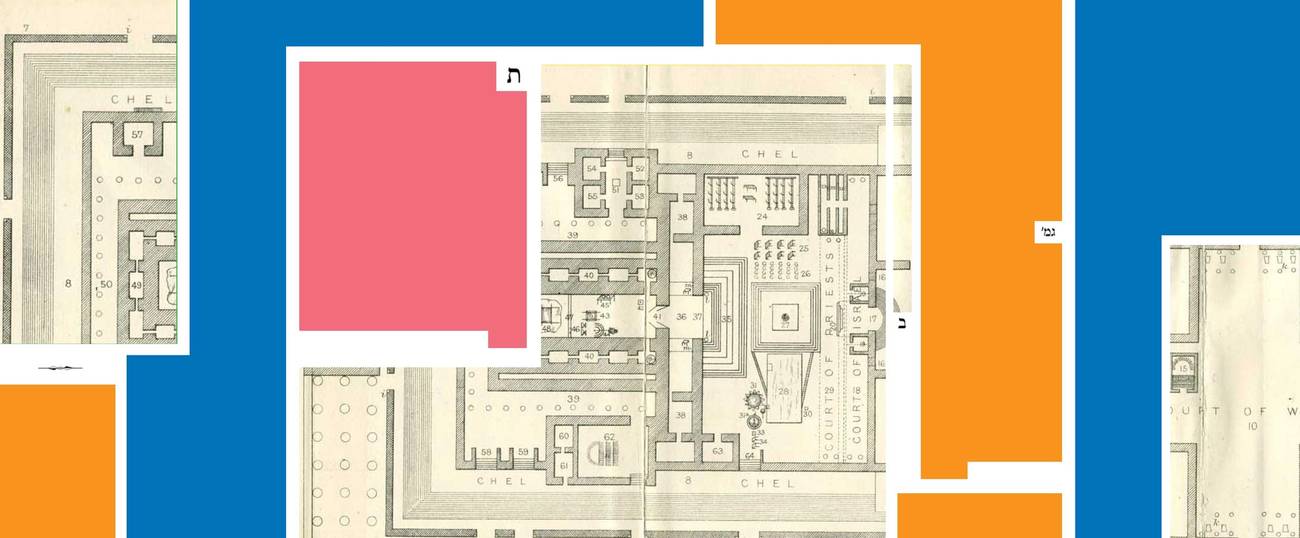

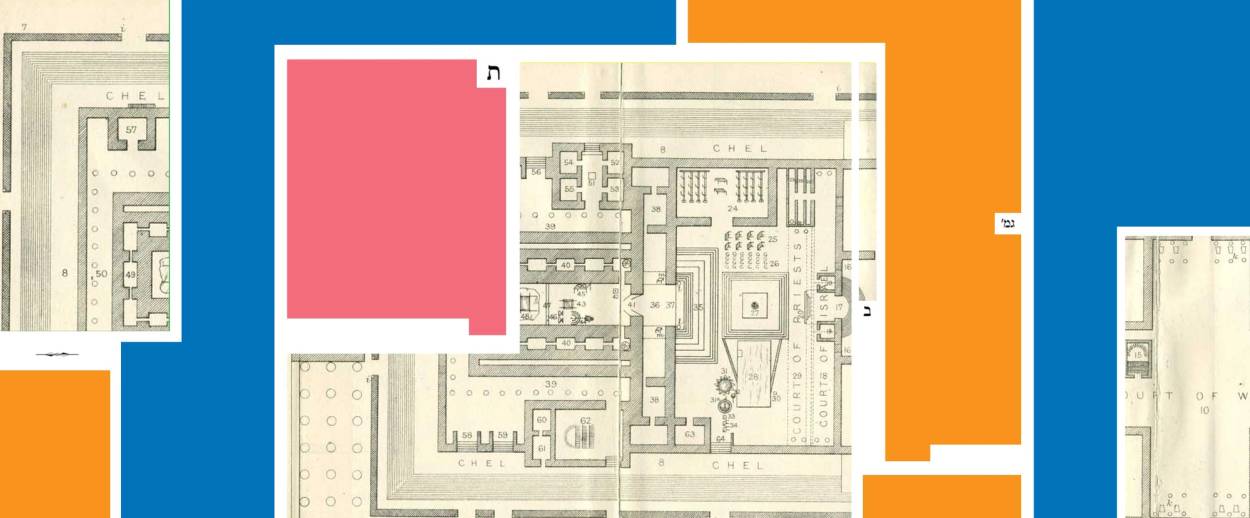

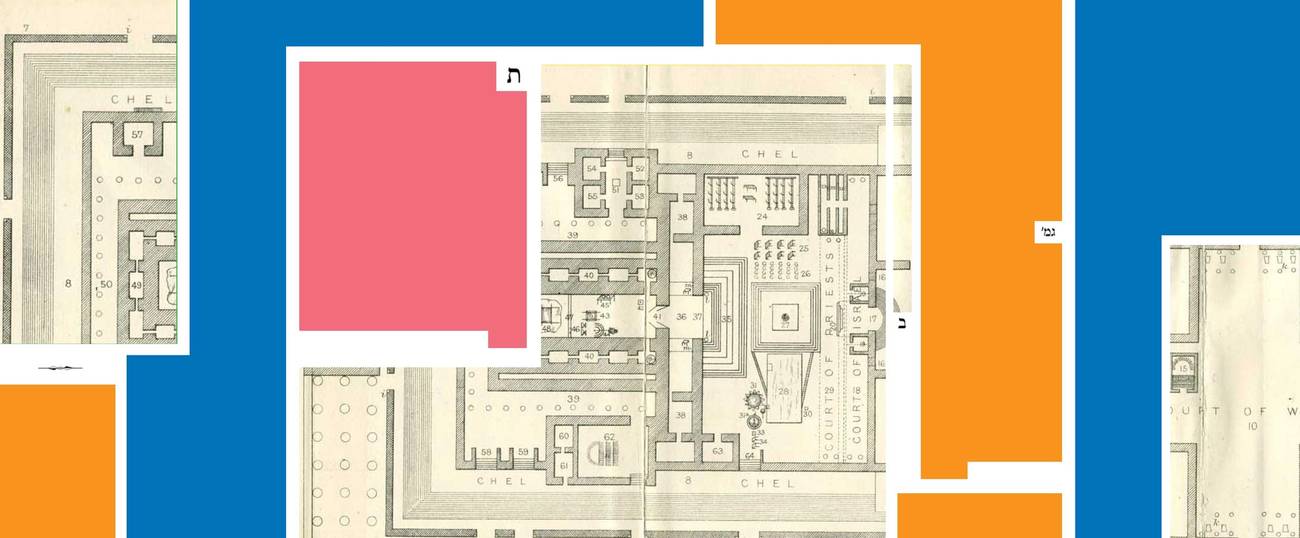

The Talmud is such a wide-ranging text that it demands a versatile reader. Depending on the subject matter, you have to have the mind of a lawyer, a mathematician, a historian, or a mystic. Perhaps that is why the Talmud could serve as the core of Jewish education for so many centuries: In studying it, your brain is put through as many different exercises as if you were carrying a full course load. This week, Daf Yomi readers were challenged to think like archaeologists, as the rabbis speculated about the exact architecture and arrangement of the Temple. But in this case we are archaeologists with no ruins or relics to guide us: All we have to go by are a few statements in the Bible and the oral tradition. (The Koren Talmud, which I am using in my Daf Yomi reading, helpfully translates the rabbis’ arguments into diagrams.)

The first knot that the rabbis seek to untie in Chapter Six of Tractate Zevachim has to do with the placement of the altar within the Temple courtyard. As we have seen over the past few weeks, the most sacred categories of offerings must be sacrificed in the northern half of the courtyard. The actual slaughter did not have to take place on the altar; rather, the animal would be killed on the ground, and then its blood would be carried onto the altar for the ritual sprinkling. However, the mishna in 58a offers the cryptic statement of Rabbi Yosei that “offerings of the most sacred order that one slaughtered atop the altar … their status is as though they were slaughtered in the north.” Evidently, sometimes animals actually were killed on the altar, and when they were, they were considered properly sacrificed.

The implication of this statement seems to be that, while the northern half of the courtyard was holier, the altar was actually situated in the southern half of the courtyard. Otherwise, there would be no need to say that it was “as though they were slaughtered in the north.” On this view, the northern half of the altar enjoys a kind of extraterritorial status: It is officially part of the north even though it is physically in the south (rather as West Berlin used to belong to West Germany even though it was surrounded by East Germany). This interpretation is backed up by the statement of Rabbi Yosei ben Yehuda that “if one slaughtered on the ground opposite the northern half of the altar, the offering is disqualified.” That makes sense if the ground next to the northern half of the altar is in fact in the southern half of the courtyard.

Another rabbi, however, makes a different formulation: “The status of the area from the halfway point of the altar and to the south is like that of the south, and the status of the area from the halfway point of the altar and to the north is like that of the north.” This seems to suggest that the altar was located in the dead center of the courtyard, so that its northern part lay in the northern half of the courtyard, and its southern part in the southern half.

And then there is Rabbi Yochanan, who maintains that “the entire altar stands in the north.” He offers no source for this statement, however, which seems curious to the Gemara: “Is it possible that this statement of Rabbi Yochanan is correct and we did not learn it in any mishna?” To remedy this lack, Rabbi Zeira embarks on a high-wire act of deductive reasoning that is hard to follow even with diagrams. Zeira quotes a mishna from another tractate that has to do with how the priests would burn wood on the altar in order to make coal, which they used for burning incense. According to that mishna, the wood was “located opposite the southwest corner of the altar, distanced from the corner northward by four cubits.” By an intricate process of deduction having to do with the rules for the location of the altar and the sanctuary, the rabbis figure out that this arrangement of the wood would only be possible if the altar stands in the northern half of the courtyard, thus backing up Yochanan’s statement.

What we are left with, then, are three mutually exclusive opinions. The altar could be in the north of the courtyard, in the south of the courtyard, or in the center of the courtyard. How can we decide between them? The answer is that we can’t, and the rabbis don’t. After providing arguments for each option, they simply move on to the next issue, which is how to deal with an altar that has been damaged. When the altar is damaged, no sacrifices can be validly offered: “all sacrificial animals that were slaughtered there are disqualified,” we read in Zevachim 59a.

What’s more, all animals that were designated for slaughter, but hadn’t yet actually been killed, are disqualified as well. The Gemara applies this rule to the animals that were living at the time of the destruction of the First Temple, in 586 B.C.E. Animals that were waiting to be sacrificed at that time were disqualified, and could not be offered even after the Second Temple was built in 515 B.C.E. The Gemara notes, however, that this is an absurd speculation, since no animal could possibly live long enough to survive from the days of the First Temple to the days of the Second, more than 70 years later.

Perhaps, then, what the rule is referring to is not the total destruction of the altar, but only damaging it. When the altar is damaged, all the animals designated for sacrifice are permanently disqualified, and cannot be slaughtered even after the altar is repaired. Apparently this happened at least once in the Temple’s history: The Talmud mentions an incident when a priest performed a water libation in a manner associated with the Sadducee sect, pouring water on his own feet rather than on the altar. This caused a riot by angry Pharisees, and in the chaos “the corner of the altar was damaged.” Evidently this required the building of an entirely new altar, since “any altar that does not have a corner, a ramp, and a base” is invalid.

All this confusion about the altar leads the Gemara to a very natural question. When the Second Temple was built, how did the builders know exactly where to put the altar? Weren’t they faced with the same confusions that the rabbis are grappling with? But the rabbis have a reassuring answer: The builders of the Second Temple were granted a vision of the altar standing in the proper place, with Michael the archangel performing sacrifices at it. Alternatively, Rabbi Shmuel bar Nachmani suggests, they were guided by scent: The whole area where the Temple had stood smelled like incense, and the area where the altar belonged smelled like cooking meat. If only the rabbis, or the modern reader, had the benefit of such angelic guidance, none of the Talmud’s difficult reasoning on the subject would be necessary.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.