Better Treyf Than Sorry

‘Daf Yomi’: To avoid conflicts of interest, Talmudic rabbis put limits on their own authority over kosher slaughter

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

Over the last six years, Daf Yomi readers have seen that the Talmudic rabbis were expert in a wide variety of subjects, not all of them what we ordinarily think of as “religious.” Yes, they had to know how to celebrate Jewish holidays and perform Temple rituals; but they were also responsible for observing the new moon, calculating the geometry of Shabbat boundaries, drawing up real estate contracts, and carrying out capital punishments. And if that weren’t enough, over the last few weeks we saw that the rabbis were experts on animal anatomy, as well. They had to be able to inspect a windpipe, a liver or a lung and know at a glance whether it was healthy or diseased, whole or injured.

Chapter Three of Tractate Chullin goes into these issues in graphic detail, as the rabbis debate what renders an animal tereifa. Most Jews are familiar with the Yiddish word treyf, which is derived from the Hebrew tereifa and is used to refer to any non-kosher food, such as pork. But in the Talmud, tereifa refers to one specific category of forbidden food: animals that are injured or diseased so that they are not expected to live for more than 12 months. Such animals are considered “torn”—the literal meaning of the Hebrew word—and so they fall under the prohibition in Exodus 22: “You shall not eat any flesh that is torn of animals in the field; you shall cast it to the dogs.”

But as Reish Lakish points out in Chullin 42a, the Torah does not mention the 12-month rule that is stated in the mishna. “Where is there an allusion in the Torah to the principle that a tereifa cannot live?” he asks. The Gemara replies with a citation from Leviticus: “These are the living things which you may eat among all the animals.” This is taken to mean that one may only eat an animal that is alive when it is slaughtered, and not a corpse or carcass of an animal that died from other causes. Because a tereifa is already on the way to dying, it doesn’t qualify as a “living thing,” and so it can’t be slaughtered.

For the rest of the chapter—an unusually long one, more than 25 pages—the Talmud catalogs all the ways an animal can be identified as a tereifa. The rabbis love to make numbered lists, and there are various enumerations here. Rabbi Yishmael, for instance, holds that there are 18 ways an animal can be “torn,” while Ulla says that “eight types of tereifot were stated to Moses on Sinai”: a perforated or severed organ, a body part that is missing or has been removed, an animal that is torn apart or clawed by another animal, or one that fell from a height or was otherwise “broken.” Hiyya bar Rava adds that there are eight internal organs that render an animal a tereifa if they are injured, including the gullet, brain, heart, lung, and intestine.

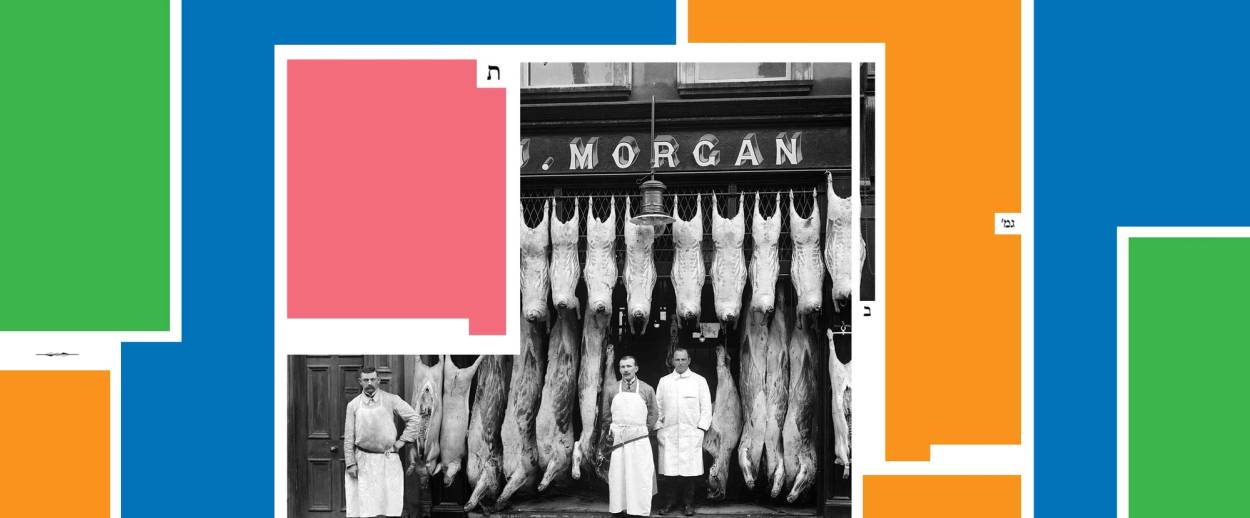

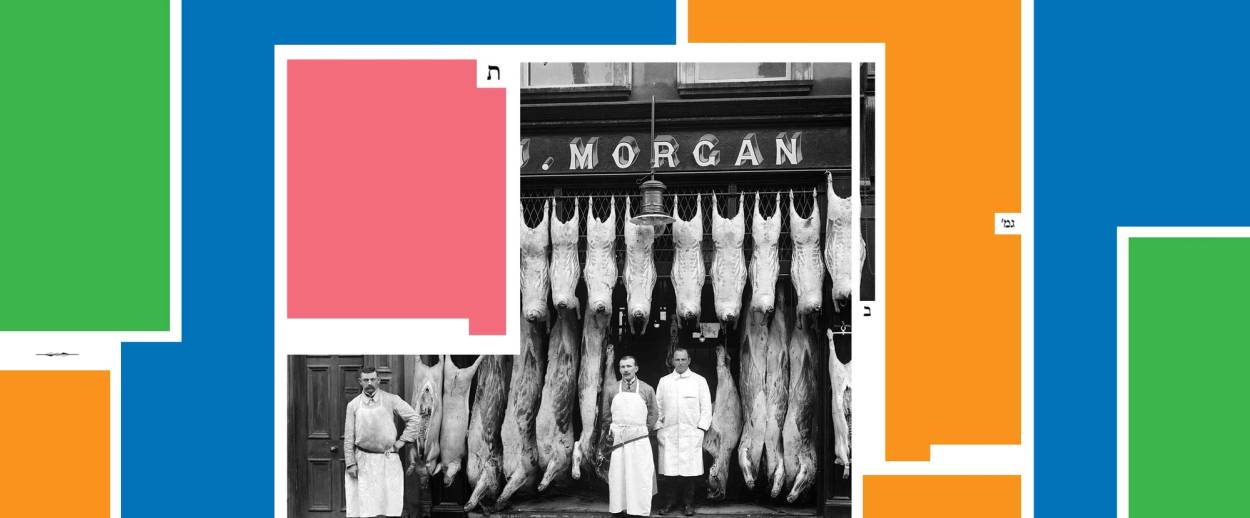

Kosher slaughter, then, involves inspecting these organs to make sure that they are not damaged. Even if the slaughter itself is carried out correctly, the animal could bear an internal injury that is invisible from the outside, and that renders if forbidden to eat. Clearly, this is a heavy responsibility for a slaughterer or rabbi, since every time he declares an animal tereifa, he is causing a significant financial loss to its owner. A slaughterer who was overly stringent in applying the rules might find himself an unpopular man—as happens to a character in S.Y. Agnon’s novel Only Yesterday, a religious fanatic who is run out of town after he invalidates too many animals. On the other hand, excessive leniency might make people suspect that they are consuming unkosher meat. In another modern novel, Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Satan in Goray, a slaughterer who curries favor with the townspeople by never ruling an animal a tereifa turns out to be a sinister heretic.

The Talmud is well aware of this dynamic. In Chullin 44b, the Gemara mentions a case where an animal with a severed windpipe was brought before Rav for examination. The rule is that the majority of the windpipe must be severed to render it a tereifa, and when Rav examined it he said that a majority was cut. But when his judgment was challenged, he sent the animal for a second opinion to another sage, Rabba bar bar Chana, who ruled that only a minority of the windpipe was cut, rendering the animal permitted. To emphasize his ruling, Rabba bar bar Chana personally bought 13 istera worth of meat from the owner (an istera being worth half a dinar).

But, the Gemara objects, isn’t there a rule against pitting one rabbi’s judgment against another in this way? “If a halachic authority deemed an item impure, another authority is not allowed to deem it pure; if he prohibited, another is not allowed to permit it,” a baraita says. In this particular case, the rule was not technically broken, because Rav was only intending to judge the animal a tereifa, but hadn’t yet officially done so. But the logic behind the rule is evident: If people could go rabbi-shopping, finding a more lenient authority to permit what another had rendered forbidden, the whole process would lose its integrity.

Rabbah bar bar Chana is open to another criticism as well. Technically, if a judge rules that an animal is kosher, it is permitted for him to purchase its meat. But this is discouraged by the sages, since it might create the impression that the judge made his ruling for his own profit or convenience. That is why the sages say, “Distance yourself from unseemliness and from things similar to it”—in other words, judges should avoid even the appearance of impropriety. On the same subject, the Gemara quotes a saying of Rav Hisda’s: “Who is a Torah scholar? One who sees his own tereifa.” The ultimate test of a sage’s honesty is when he rules that his own animal is forbidden to eat: He is willing to take a financial loss in order to uphold the law.

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.