Blood and Milk

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi’: Why are Jews allowed to drink milk at all? Plus: what Talmudic rabbis misunderstood about menstruation and the sources of other bodily fluids. Also: the right way to sacrifice a donkey.

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

Why are Jews allowed to drink milk? It never occurred to me that the question needed to be asked until last week, when it arose in the first chapter of Tractate Bekhorot, which Daf Yomi readers began during Passover. “Bekhorot” means “firstborn”: Coincidentally, the word appears prominently in the Haggadah in the list of the 10 plagues, which culminates in makat bekhorot, the plague that killed the firstborn sons of the Egyptians. In the Book of Numbers, that plague is given as the reason why the firstborn sons of Jewish mothers, as well as the firstborn male offspring of kosher animals owned by Jews, are consecrated to God: “On the day that I smote all the firstborn in the land of Egypt I sanctified for Me all the firstborn in Israel, both man and beast.”

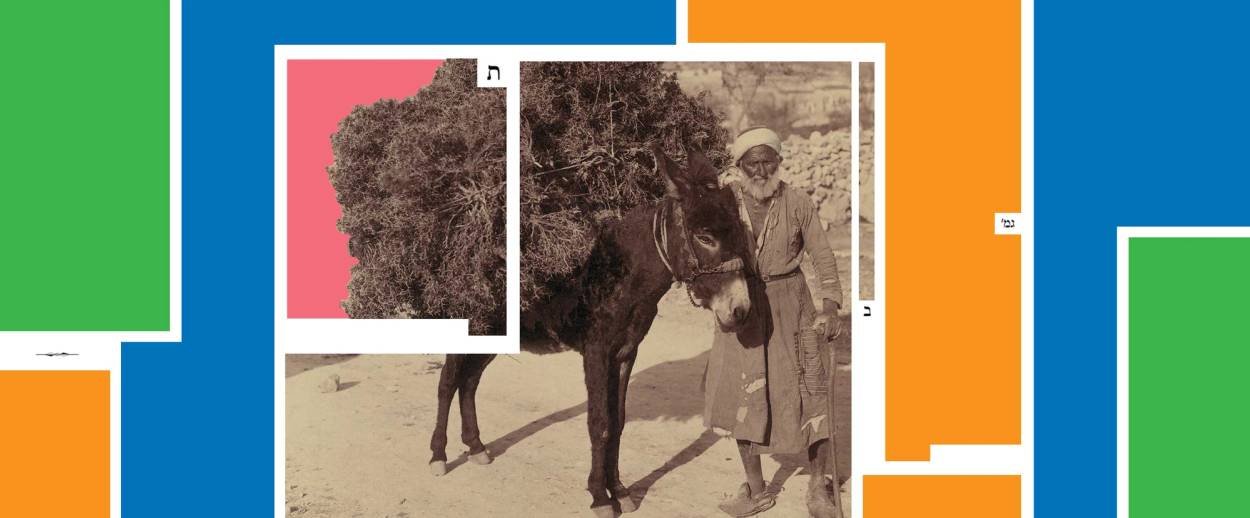

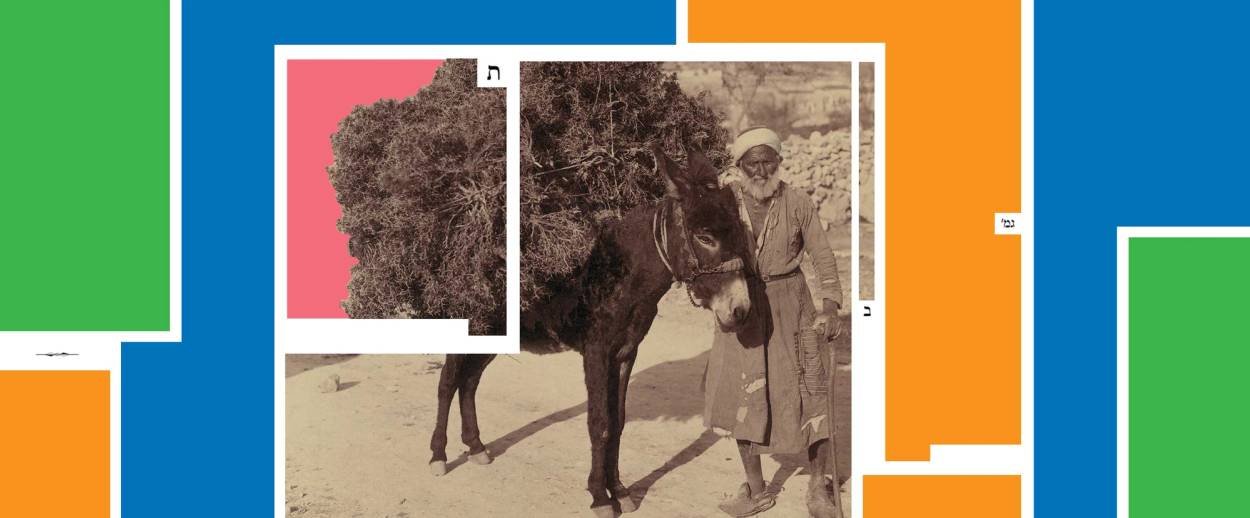

While the Temple stood, the firstborn male offspring of every kosher animal had to be given to the priests, who sacrificed it on the altar and ate the meat. In addition to human sons and kosher animals, however, one other species is included in the consecration of the firstborn: donkeys. Donkeys aren’t kosher—they don’t chew their cud and they lack cloven hooves, the two criteria for kosher animals—so they can’t be sacrificed in the Temple and eaten. Instead, a Jew is supposed to redeem the firstborn donkey by sacrificing a lamb in its place; if he can’t or doesn’t want to do this, he must kill the donkey by breaking its neck.

Why are donkeys singled out for consecration among all nonkosher animals? “In what way are donkeys different from firstborn horses and camels?” asked Rabbi Chanina. Rabbi Eliezer replies that no explanation is necessary: “It is a Torah edict,” and there’s no need to look for reasons for God’s commandments. But this doesn’t stop Eliezer from offering an explanation anyway: It is because donkeys “assisted the Jewish people at the time of their Exodus from Egypt.” The Israelites used donkeys to carry their possessions, including the “silver and gold” they seized from the Egyptians as reparations for slavery. “There was not one member of the Jewish people that did not have 90 Nubian donkeys with him,” Eliezer says, though it’s not clear where he gets this figure.

Tractate Bekhorot deals with many issues that arise from the basic commandment of redeeming the firstborn. The first chapter, in typical Talmudic fashion, begins not by laying out the law itself or the reasons behind it, but by plunging in to deal with a specific problem. What happens, the mishna inquires, when a Jew enters into a transaction with a gentile involving the fetus of a pregnant donkey? If a Jew sells a yet-to-be-born firstborn donkey to a gentile—that is, he takes money now in exchange for the promise of handing over the donkey when it’s born—who is the legal owner when the donkey emerges from the womb, the Jew or the gentile? Conversely, what if the Jew buys a fetus from a donkey owned by a gentile?

These are important questions because, if the Jew is the legal owner of the newborn, the donkey is automatically consecrated and must be turned over to the priests; whereas if the gentile is the owner, it is not consecrated. The mishna answers that, in either case, the donkey is not consecrated because it is partly owned by a gentile, and the Torah specifies that God only claims “all the firstborn in Israel.” According to Rav Huna, this is true even if the Jew and the gentile are unequal partners—for instance, if the Jew transfers ownership of just the ear of the donkey to a non-Jew, it is born unconsecrated.

As the rabbis are not slow to observe, however, this opens the potential for legal chicanery. A Jew could sell the ear of an unborn donkey to a gentile simply so that he wouldn’t have to hand the whole donkey over to the priests when it was born. Indeed, in Bekhorot 3b, the Gemara says that a sage called Rav Mari bar Rachel once tried this very trick. (It is unusual in the Talmud for a man to be described as the son of his mother—“bar Rachel”—rather than of his father. The Koren Talmud explains that this is because his father was a gentile, so he is referred to as the son of his Jewish mother.) Rav Mari “would transfer ownership over the ears” of his flock’s unborn offspring to a gentile, so they wouldn’t technically be considered firstborn. But while the rabbis can’t close this legal loophole, God can: “The animals of Rav Mari bar Rachel died,” the Gemara notes with satisfaction.

In time, the discussion comes around to the issue of unkosher animals like camels and horses. Clearly these animals can’t be eaten; but how do we know that their milk, too, is forbidden? The reason is that rabbinic law forbids “the juice and the gravy and the sediments” of a nonkosher animal along with its meat, and milk falls into this category. Then the Gemara goes on to ask a further question: How do we know that the milk of even kosher animals, like cows, is permitted for consumption?

One might have simply taken this for granted; but in Bekhorot 6b, the rabbis raise a problem connected with their premodern understanding of animal biology. One of the central rules of Jewish dietary law is that Jews are forbidden to consume blood. But the rabbis believe that the milk of an animal is actually the same thing as its blood: In a nursing mother, “the blood is spoiled and becomes milk.” So why are we allowed to drink milk, if it’s just blood in another form?

Of course, to say that milk is blood is factually incorrect. The Koren Talmud interprets the Talmud’s words, rather generously, as a way of saying what a modern biologist knows, that the milk gland of an animal “synthesizes ingredients received from the bloodstream, such as calcium, protein, fats and sugar.” But the rabbis knew nothing about glands or the circulation of the blood; what they seem to be saying is that milk actually is blood.

They were led to this belief by the fact that a nursing mother doesn’t menstruate. Today, we know this is because nursing produces hormones that inhibit menstruation. But for the rabbis, it seemed to prove that the blood which ordinarily would be discharged in menstruation had been converted to milk inside the mother’s body. (At least, this is one Talmudic theory about why nursing mothers don’t menstruate. Another theory is that, after childbirth, “her limbs become disjointed and her soul does not return to her until 24 months later.”)

Yet somehow, it is still permitted to drink milk. As the Gemara says, this is a hiddush, a legal novelty—in other words, something that could not have been deduced from known legal principles. Thus the Torah must state it as a separate rule. But the rabbis have a surprisingly hard time finding a Torah verse to permit milk consumption. There is a verse that forbids eating meat cooked in milk (which was discussed extensively in the previous tractate, Chullin): As the Gemara observes, this seems to imply that “milk by itself is permitted.” But the Gemara objects that perhaps this only implies that milk is permitted “for benefit”—that is, Jews can buy and sell it, but not consume it.

What about Proverbs 27:27, which says, “And there will be goats’ milk enough for your food”? This seems straightforward; but again, the Gemara objects that it could be taken to mean that the milk is to be sold and the proceeds used to buy food. Then what about the episode in the book of Samuel where the young David is sent to meet his brothers, who are in the army battling Goliath and the Philistines, carrying “10 cheeses”? Surely this shows that cheese, a dairy product, is permitted to eat. The Gemara tries its objection once again—maybe David was supposed to sell the cheeses and give the money to his brothers?—but this seems inherently unlikely: “Is it the norm during war to engage in commerce?” the rabbis demand.

Finally, the rabbis point to the famous verse from Exodus that describes the land of Israel as “a land flowing with milk and honey.” “If milk was not permitted, would the verse praise the land with an item that is not suitable for consumption?” the Gemara asks. This not only proves that milk is permitted; it does the same thing for honey, which is open to the objection that it is made by bees, which as insects are not kosher. But honey, the rabbis say in Bekhorot 7b, is not technically produced from the body of the bee; rather, it is made from the nectar of flowers, and the bee merely carries it. This is a happy ending to the debate: No one minds being forbidden to eat bees, but a Jewish diet without honey would be a lot less sweet.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.