Clergy on the Front Lines

Hospital clergy adjust to new rules and procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic

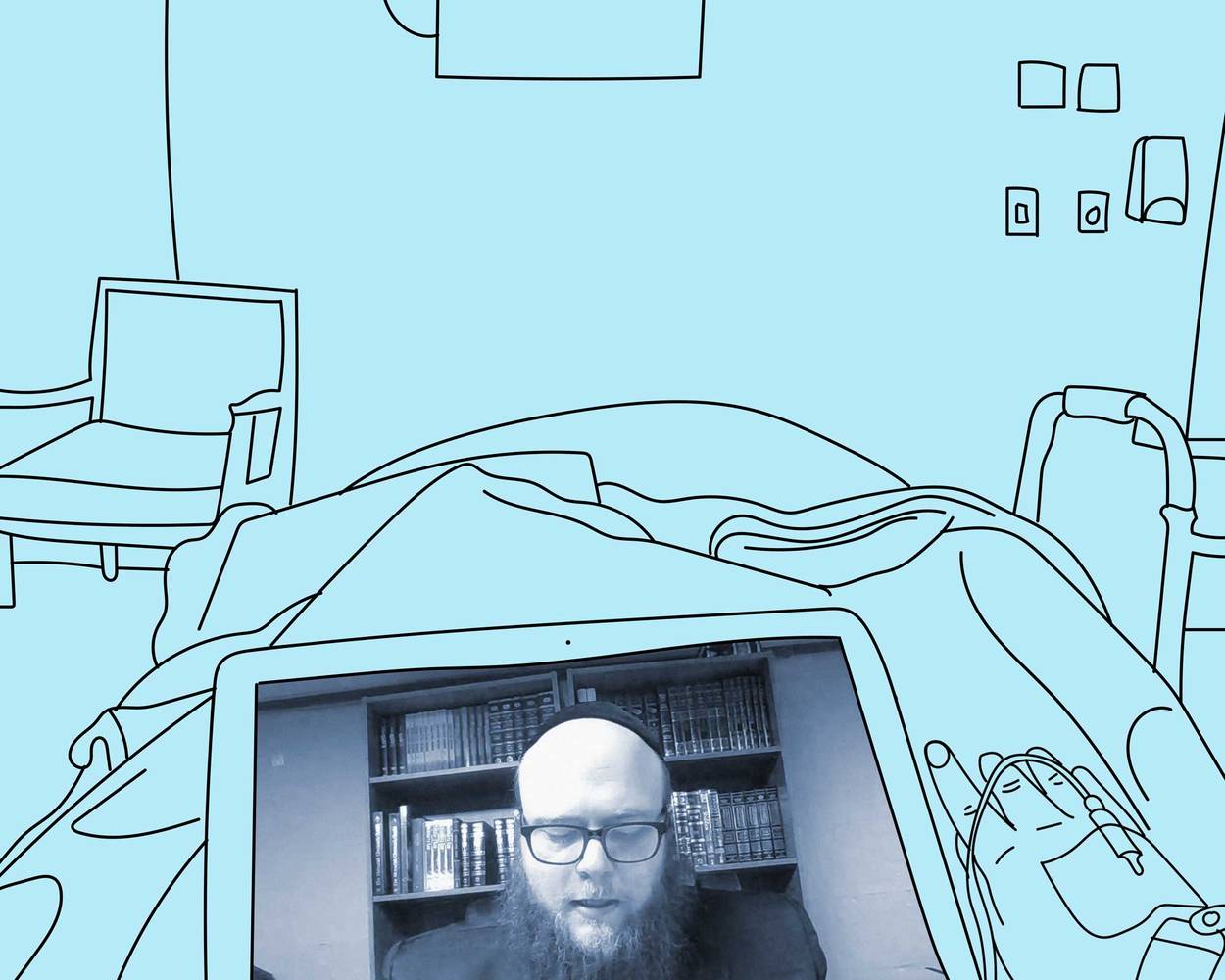

As Rabbi Benyamin Vineburg chanted the moving words of the vidui, the Jewish confessional prayer, to a COVID-19 patient dying in the intensive care unit, the family was there, too. But this was different from the countless other times he’d said the vidui. Vineburg, a chaplain resident at the University of Michigan Medical Center, sat in his home in Oak Park, Michigan, miles away from the Ann Arbor hospital. The family was home, too. A nurse clothed in protective gear held the phone to the patient’s ear, the timing carefully coordinated to conserve equipment. The patient, intubated and drifting in and out of consciousness, was nearing his last breaths.

As medical professionals have adapted to the changing norms of COVID-19, hospital chaplains have been unsung heroes. Forced to adapt to the constraints of new visitation policies and in many cases virtual chaplaincy, coupled with a massive death toll and rising spiritual need, chaplains have had to quickly innovate.

“It’s made chaplaincy a lot harder and a lot more painful for us because we realize the needs of people to have interpersonal attention and validation has not changed, but has become more critical. And our ability to provide it has become more difficult,” said Vineburg.

Rabbi Sara Adler, another chaplain at University of Michigan Medical Center, works from home five days a week. A few “in-house” chaplains are largely there to support staff, who have also faced unprecedented burdens; even so, room visits are reserved for special circumstances such as priests administering the last rites, which traditionally must be done in person. Adler notes the emotional toll this has taken on her: “In person … you can read people’s body language; you can communicate with your own facial expressions the sadness that we feel when we’re hearing their stories,” she said. “I worry about how much I really can communicate with my voice over the phone … it’s a different kind of interaction. It’s less than ideal, but at least we feel like we’re doing something.”

For those still able to be in the hospital, this presents its own set of challenges. In New York City, the epicenter of the virus, Rabbi Jason Kirschner spends three days a week working from home, and two days at the Mount Sinai Hospital, where he serves as staff chaplain and rabbi. He does not, however, enter the rooms of COVID-19 patients, and he wears an N95 respirator in all rooms, given he never knows who may test positive for the virus.

“A lot of what chaplains do is based on seeing a patient who has emotions … and you returning those emotions through facial cues … I can’t smile anymore at my patients because any room I go into I’m wearing an N95 respirator. Between that and not being able to touch a patient, it takes away a lot,” said Kirschner.

Rabbi Jason Weiner, senior rabbi and director of the Cedars-Sinai Spiritual Care Department in Los Angeles, is in the hospital nearly seven days a week. At Cedars-Sinai, chaplains are permitted in all rooms, including those of COVID-19 patients, except for those in the ICU. Given the restrictive visitation policy, chaplains have served as liaisons between patients and their families in addition to their more traditional roles. At one family’s request, for instance, Weiner told a comatose patient that his granddaughter had been accepted to UCLA, because if the patient did not make it, she wanted him to hear before he died.

In April, Weiner wanted to ensure Jewish patients knew when it was Passover.

“Like all of us nowadays who don’t even know what day of the week it is, it’s so much more so for these patients who get rushed to the emergency room and the next thing you know they’re intubated and in a coma for three weeks and they wake up. So before Passover I put up signs on the outside of each room facing in that said Happy Passover in English and chag sameach in Hebrew so that when they woke up they would know,” said Weiner.

Hospital visitation policies vary across the country. At Cedars-Sinai, family members initially were not allowed in for any reason, including at the end of life. Weiner saw it as his duty to help ensure that certain rituals requested by the family were observed and to help provide comfort based on the Jewish belief that the soul is afraid as it is leaving the body. When going into the room was not possible, he would stand outside the door and recite prayers through the glass, hoping the patient would hear and be comforted. Sometimes, the nurses, who were permitted in ICU rooms, served as conduits for the rituals.

Weiner recounts praying outside of the room of a COVID-19 patient into a phone, the nurse inside putting him on speaker so the patient could hear. After the patient died, the nurse said: “‘Rabbi, I really want to respect this patient and I feel so badly that his family’s not here. What else should I do?’ I said, ‘There are a lot of customs—normally we close the eyes, close the mouth, make the arms straight … but are you allowed to do that? That’s a lot of extra handling of the body.’ And she was like, ‘I don’t know if I’m allowed to do that. I have no idea.’ None of us knows. We’re all learning as we go.”

Now, restrictions have slightly loosened, and family members at Cedars-Sinai are allowed to be with a dying patient for 15 minutes to say goodbye. “Obviously leaving the room was like torture, because they had to leave for the last time and really say goodbye literally and then wait for the news. … We’re trying to say, when you leave, we’ll keep checking in. We’ll call you by FaceTime or we’ll sit in the room when we can or just keep a vigil,” said Weiner.

But like other workers on the front lines, chaplains fear for their own safety and the safety of their family members. “At the beginning there was a chaplain who died from COVID in New York. He got it and he died and it was so scary … and to recognize that we’re putting ourselves at risk, and theoretically we don’t have to be, I mean we’re not essential in the way doctors and nurses are … but we still feel like we have to be there on the front lines, and the risk is a little scary,” said Weiner.

Despite the challenges, COVID-19 has brought spirituality to the forefront along with a new sense of togetherness. “I’ve had really sick patients wanting me to come and pray with them for the COVID patients. People’s goodness is there. It’s just blown me away,” said Rabbi Susan Stone, director of spiritual care at Cleveland Clinic Hillcrest Hospital.

“I think that COVID has created a spiritual awakening in people like we’ve never seen before,” said Vineburg. “We as chaplains are encouraging people to come out of COVID different than when they went in.”

Netana Markovitz is a medical student at the University of Michigan and has a B.A. in English from Columbia University.