The Talmudury Tales

Women without underarm hair, transvestites seeking illicit sexual relations, lepers who can’t shave, nazirite gentiles, grape-eaters, and other Chauceresque characters, in this week’s ‘Daf Yomi’

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

Throughout Tractate Nazir—whose end Daf Yomi readers approached this week—there has been a very natural assumption that the only people who can become nazirites are Jews. Indeed, it never occurred to me that it could be otherwise: Isn’t naziriteship a part of Jewish law, as laid down in the Torah? Yet in Nazir 61a, the rabbis point out that the textual basis for naziriteship, in the Book of Numbers, is not crystal clear on this point. The subject is introduced with the words, “Speak to the children of Israel and say to them: When a man or woman shall clearly utter a vow, the vow of a nazirite, to consecrate himself to the Lord.” The phrase “speak to the children of Israel” seems to imply that what is to follow—the rules and restrictions of naziriteship—is intended for Jews only.

But then the biblical text says “a man or woman,” which suggests that any man or woman, Jew or gentile, is capable of “uttering the vow of a nazirite.” Indeed, the Gemara finds an example in another part of the Bible where “man” is taken to mean just that. The Book of Leviticus establishes the practice of “valuation vows,” in which you can consecrate a person to the Lord by donating his or her equivalent value in cash. The Bible gives a table of values for different kinds of people, from 50 shekels for an adult male down to 3 shekels for a baby girl. Here, in Leviticus 27:2, the text reads, “When a man shall clearly utter a vow of persons to the Lord, according to your valuation.” And in this case, the rabbis say, “a man” definitely includes a gentile; it is possible to make a non-Jew the subject of a valuation vow. If that is so, then shouldn’t the word “man” be equally capacious when it comes to naziriteship? How can “man” mean “any man” in one place and “a Jewish man” in another?

In the face of this difficulty, the rabbis look for other reasons why a gentile is not eligible to become a nazirite. In doing so, they raise some interesting questions about the status of non-Jews in Jewish law. As a general principle, the Talmud holds that non-Jews have no legal responsibilities under Jewish law. For instance, in Nazir 61b, the Gemara states that “a gentile does not have a father.” This sounds pejorative, or simply absurd; but of course it is not to be taken as a statement of biological fact or filial feeling. It simply means that gentiles are not bound by the legal obligations toward their fathers that Jews must follow—including the obligation in the fifth commandment, “Honor your mother and father.”

Likewise, non-Jews are not subject to the laws of ritual purity—they cannot contract tumah. The rabbis deduce this from a verse in Numbers that states, “But the man who shall be impure and shall not purify himself, that soul shall be cut off from the midst of the assembly.” Since the assembly in this case is the people of Israel, it follows that only a member of the people can become impure. And since the avoidance of impurity is a central part of naziriteship, it follows that non-Jews cannot become nazirites. The discussion of this issue goes on for several more pages, leading me to wonder whether this question was purely theoretical, or whether there was ever a case of a non-Jew asking to become a nazirite. After all, we know that in the Roman period some gentiles, even Roman aristocrats, sometimes became what were called “god-fearers,” non-Jews who worshiped the Jewish God. Could some of them have wanted to take a further step and join the spiritual elite of nazirites?

The Talmud goes on to consider other categories of people whose ability to become nazirites is limited. Can a slave become a nazirite? The answer is ambiguous: A slave can take the nazirite vow, but his owner can compel him to violate it at any time. For instance, even though a nazirite is not permitted to eat grapes, a slave’s master can force him to eat them, on the principle that refusing nourishment would leave the slave less able to work and thereby damage the master’s investment. Oddly, however, if the slave took a vow refusing to eat a specific bunch of grapes—a vow of the kind we studied in Tractate Nedarim, where you can swear not to “derive benefit” from a certain object—the master could not force him to violate that vow. This is because, if a slave vowed not to eat one bunch of grapes, the master could easily substitute a different bunch, thus achieving the same end without violating the vow. With naziriteship, however, any grapes would be equally off-limits; so the master can force the slave to eat them, since there is no easy way around the prohibition.

Legally, however, while a master can force a slave to break his nazirite vow, he can’t actually nullify that vow. The slave remains a nazirite, though a delinquent one; as a result, if and when he is “emancipated, he completes his naziriteship.” This means that a slave actually has greater freedom than a wife, for as we have seen earlier, a husband can completely nullify his wife’s nazirite vow for any reason—even if it is simply that he doesn’t like the idea of her shaving her head.

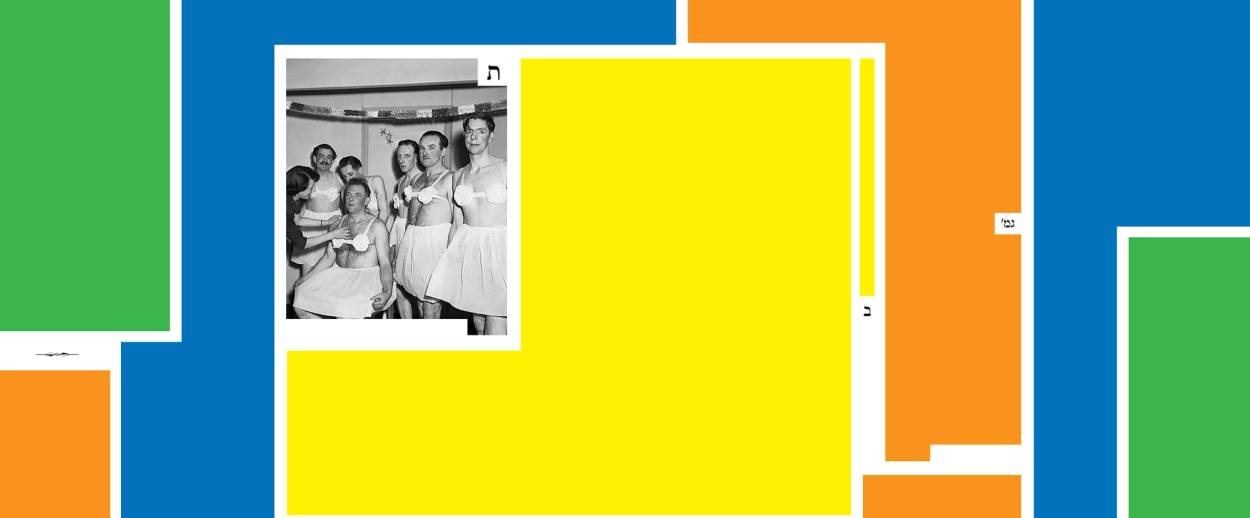

Earlier in this week’s reading, in chapter 8 of the tractate, the Talmud took up questions of transvestism and personal grooming. The discussion begins by addressing the issue of a nazirite who contracts leprosy and thus becomes subject to contradictory laws: A nazirite is forbidden to shave, but a leper is commanded to shave as part of his purification process. In this case, the rabbis invoke the principle that a positive mitzva overrides a negative mitzva: The leper’s commandment to shave is more important than the nazirite’s commandment not to shave.

Once the subject of shaving has come up, Rav opines that “a person who is not a nazirite may lighten his burden by removing all the hair of his body with a razor.” The Bible makes clear that a Jew cannot shave his beard or sidelocks, but all other body hair seems to be fair game. But the Gemara raises an objection, on the grounds of gender confusion: “A man who removes the hair of the armpit or the pubic hair is flogged,” the rabbis say, for transgressing the biblical prohibition “A man shall not put on a woman’s garment.” This seems to suggest that, in Talmudic times, it was common for women to shave these areas, so that if men followed suit they would be engaging in a “feminine” practice.

The rabbis, however, seem to have trouble understanding this biblical injunction. The Bible describes cross-dressing as an “abomination,” but “there is no abomination here,” the Gemara says in Nazir 59a. Already in Talmudic times, the biblical rule seemed excessively puritanical. Rather than rejecting the rule, however, as we might do today, the rabbis took the characteristic approach of reinterpreting it. If the Bible banned cross-dressing, it was not simply because wearing the wrong clothes was an abomination, a sexual crime. Rather, it was “so that a man may not wear a woman’s garment and sit among the women; and a woman may not wear a man’s garment and sit among the men.” Dressing up as the opposite sex, in this view, was a disguise, meant to facilitate illicit sexual relationships. It would seem to follow that transvestism for its own sake would be perfectly all right under Talmudic law—though somehow I doubt that this is the view taken by Jewish tradition.

***

To read Tablet’s complete archive of Daf Yomi Talmud study, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.