Myth and Meaning

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi’ Talmud study, the ancient rabbis take personal ownership of their Torah interpretations, as they map the spaces that separate the holy from the mundane

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

In this week’s Daf Yomi reading, in Zevachim 48a, the Gemara introduced a concept that helps to illuminate the worldview of the rabbis. A certain teaching, we read, “is dear to the tanna”: he has a special attachment to a particular point of law. And the reason is that this point is “derived through interpretation”: that is, it is not stated explicitly in the Torah, but has to be worked out by the rabbis themselves. Evidently, the rabbis had a particular fondness for laws that they had to figure out on their own, and liked to teach such laws first, because they were “dear.” I found this a moving idea, since it shows how the rabbis invested their feelings (and their egos) in what might seem like an abstract or technical process of legal reasoning. A tanna who solved a problem must have felt a certain pride of ownership in it, the way a mathematician might feel about an especially difficult proof.

Just how difficult rabbinic reasoning can get was made clear in this week’s reading, most of which dealt with the extremely complex rules governing Torah interpretation. There are a few primary tools that the rabbis use to deduce Jewish law from the text of the Torah, including juxtaposition (two matters taught next to each other are held to be similar); verbal analogy (the same word used in different contexts indicates that they are related); and a fortiori inference. Things get really complicated when the rabbis begin to wonder how these tools interact. For instance, can a matter derived from a juxtaposition then serve as the basis for a verbal analogy? There are many possible permutations, and the Koren Talmud tries to help the reader by summarizing the long rabbinic discussion in a chart.

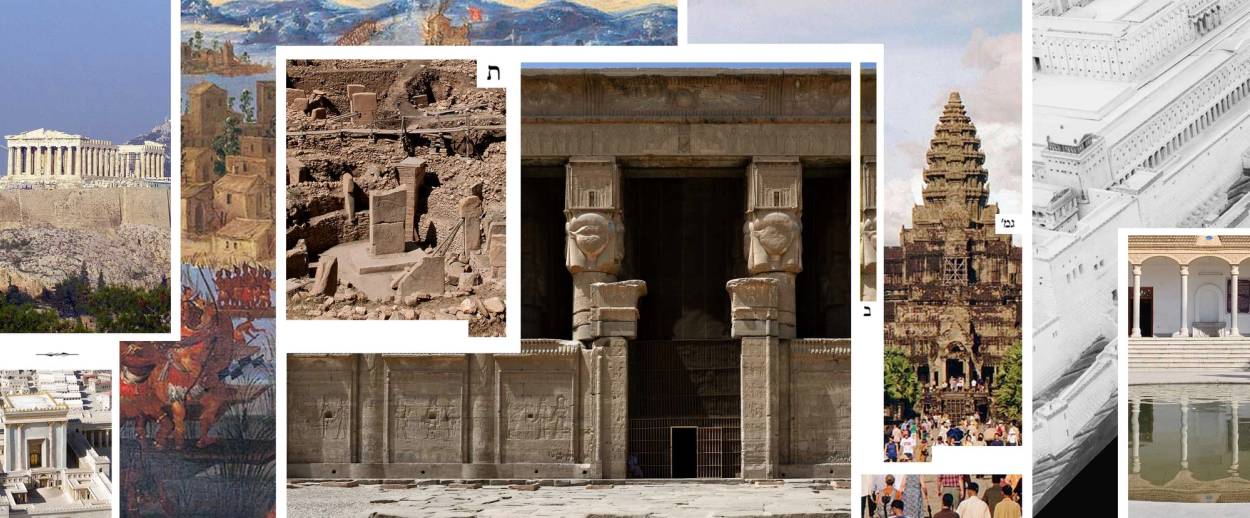

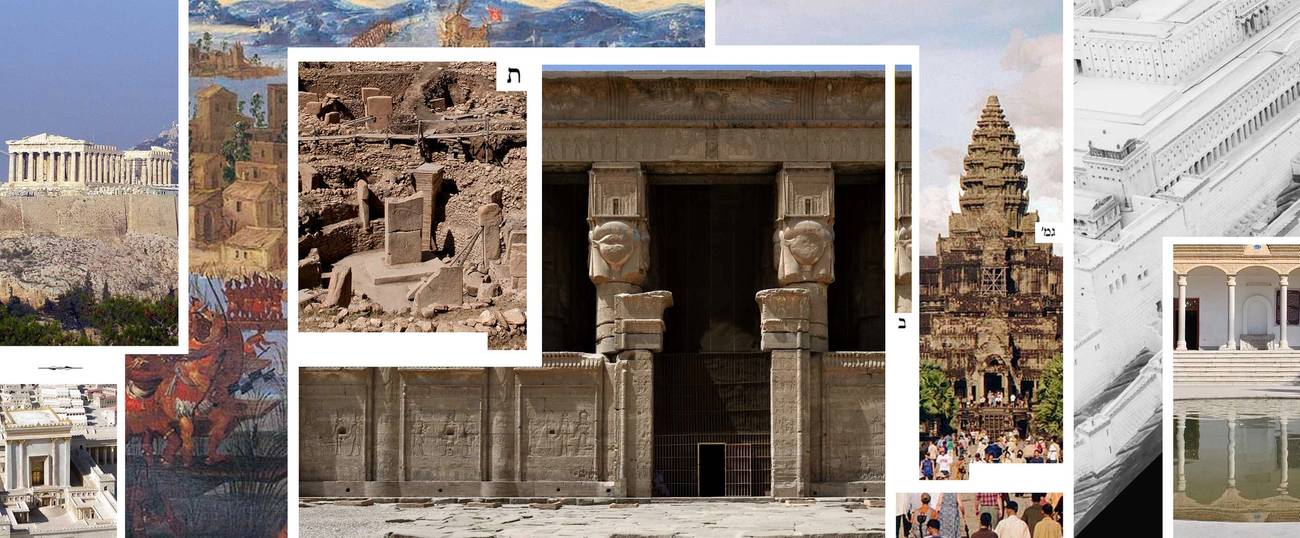

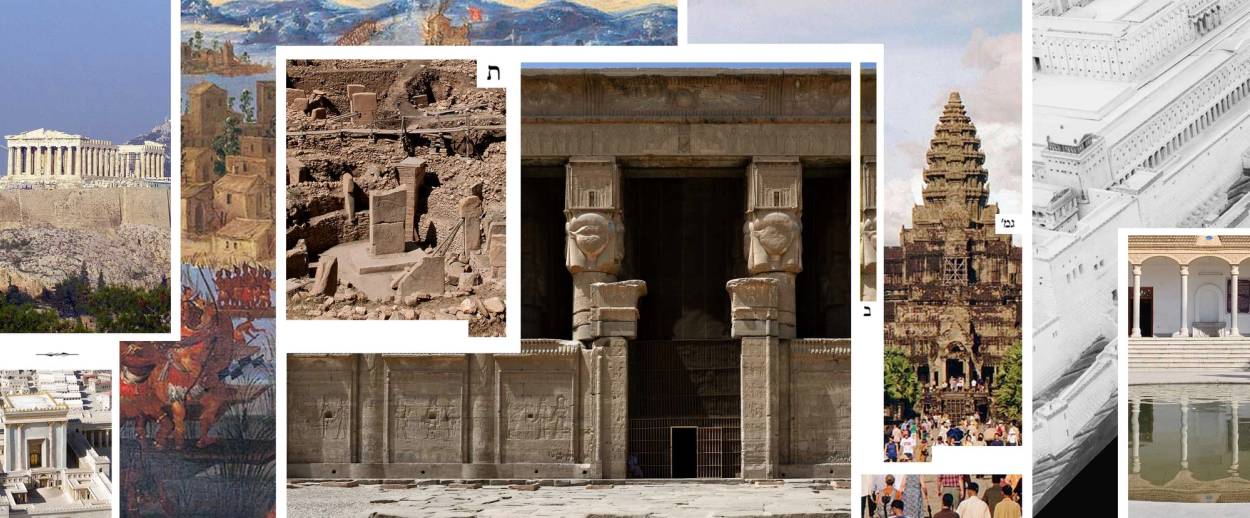

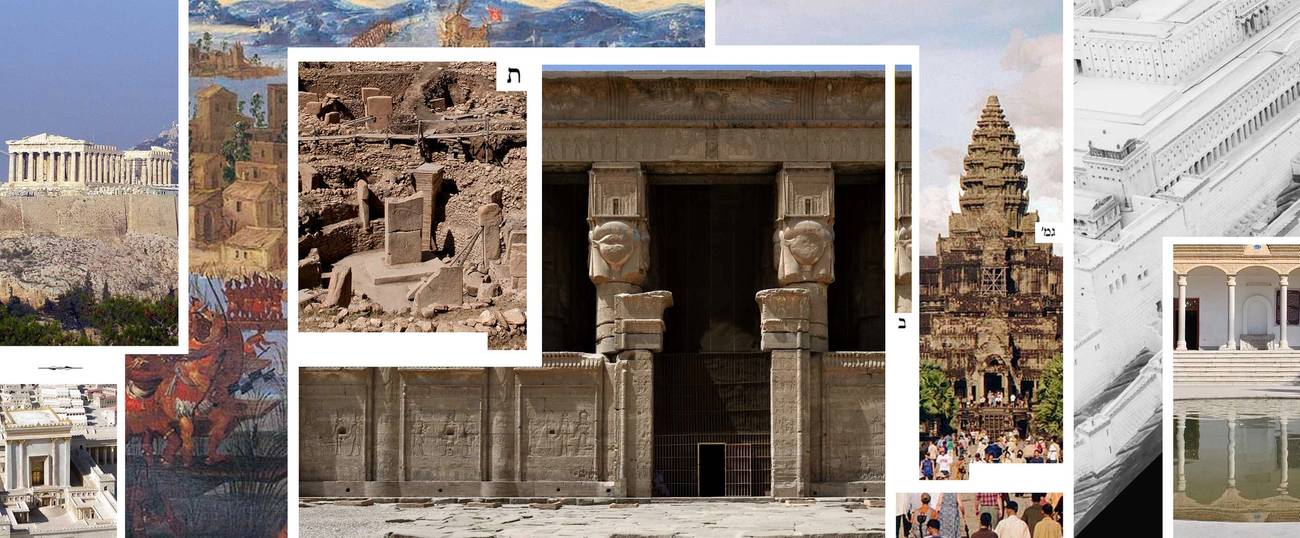

But the teaching the Talmud refers to as “dear” concerns a simpler matter. “What is the location of offerings?” asks the first mishna of Chapter Five of Tractate Zevachim, which Daf Yomi readers began this week. That is, exactly where in the Temple are animals supposed to be slaughtered? When it comes to “offerings of the most sacred order,” including sin and guilt offerings, we learn that “their slaughter is in the north”: the northern half of the Temple courtyard is considered to be holier than the southern half. The basis for this distinction is found in Leviticus 1:11, which teaches the procedure for burnt offerings—sacrifices in which the entire animal is burned, so that God can enjoy the smell of the meat, “an aroma pleasing to the Lord.” With such sacrifices, the Torah says, “You are to slaughter it at the north side of the altar before the Lord, and Aaron’s sons, the priests, shall splash its blood against the sides of the altar.”

In the time of Aaron, of course, there was no Temple and no Jerusalem; offerings in the desert were made in the Tabernacle, the portable tent where the Ark of the Covenant resided. But the Tabernacle was a kind of forerunner to the Temple, and every law governing the Tabernacle was applied to the Temple once it was built. (Alternatively, one might believe, with modern biblical scholarship, that the portions of the Torah dealing with the Tabernacle were actually written during the time of the First Temple, and that the priests projected the rules of their own time backward into the mythical time of Aaron and Moses.)

No rational explanation is given, or can be given, as to why God prefers the north side of the altar to the south side. The organization of space in terms of sacred and profane is one of the oldest and most mysterious forms of human creativity. As the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss showed, it is a common attribute of early civilizations, a way of organizing the world in order to give it meaning. A world that is featureless, undifferentiated space would be impossible for us to live in—it would be the world of physics, not of history and culture. We domesticate the world by arranging its space according to our own categories of meaning: inside and outside, holy and profane, home and away. In this sense, God’s preference for the north side of the altar needs no special explanation, since the entire Temple—with its hierarchical system of areas and courtyards, leading up to the Holy of Holies—can be considered a tool for imposing human categories on the world.

The question of why the north side is holier than the south does not arise for the rabbis, of course. It’s stated in the Torah and that’s the only answer necessary. But the rabbis do have a problem to solve. The Torah only states this preference for the north with regard to burnt offerings, but the rabbis teach that the same rule applies to sin and guilt offerings. In particular, “the bull and the goat of Yom Kippur”—the most important offerings in the Temple calendar, which achieve atonement for the sins of the whole Jewish people—are also offered in the north of the Temple. “Their slaughter is in the north and the collection of their blood in a service vessel is in the north,” the mishna says. The Gemara goes on to add that the priest officiating over these ceremonies must stand in the northern half of the Temple courtyard, and that the offering is disqualified if he stands in the southern half.

What is the basis for treating sin and guilt offerings in the same way as burnt offerings, with regard to the requirement of offering them in the north? The answer comes from another verse in Leviticus, which says, “in the place where the burnt offering is slaughtered shall the sin offering be slaughtered before the Lord.” Clearly, the Torah treats the burnt offering as primary: It is the paradigmatic case, from which the rules governing the sin offering are derived. So why, the Gemara asks, does the mishna begin by teaching the case of the Yom Kippur sin offering? “Let the tanna of the mishna teach the halacha of a burnt offering first,” the Gemara proposes.

And this is where the notion of a “dear” teaching comes in. “Since the location for slaughtering the sin offering is derived through interpretation, it is dear to the tanna.” the Gemara explains in Zevachim 48a. The tanna—the rabbinic authority in whose name the mishna is taught—prefers to begin with the sin offering because it requires some intellectual effort to figure out. As always in the Talmud, Jewish law is the product of the collaboration of the human mind and the divine will.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.